To Walt Whitman, America

Acknowledgments

I began this book at Texas A&M University, expanded its range and altered its orientation at the College of William & Mary, and completed it at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. I am grateful for support of various kinds from each of these institutions. I owe much to Ed Folsom, Elizabeth Gray, Ezra Greenspan, Sian Hunter, and Marilee Lindemann, each of whom read the entire manuscript and enriched it significantly. Other readers improved the book by commenting on particular sections: Brett Barney, Susan Belasco, Stephanie Browner, Matt Cohen, Jeffrey N. Cox, Linda Frost, Amanda Gailey, Andrew Jewell, Wendy Katz, Diana Linden, Jerome Loving, Arthur Knight, Richard Lowry, Martin Murray, Robert K. Nelson, Mary Ann O'Farrell, Venetria Patton, Vivian Pollak, Larry Reynolds, Michael Robertson, Robert Scholnick, and George Wolf. My wife Renée and daughters Ashley and Gillian helped in ways large and small—and also in ways that defy description. Their presence is everywhere in these pages.

For permission to reprint, in Chapter 1, a single paragraph from my coauthored essay published in American Literature, I am grateful both to Robert K. Nelson and to Duke University Press. I am similarly grateful to Texas Studies in Literature and Language for allowing me to reproduce, in Chapter 2, a modified version of an essay on Edith Wharton and Whitman. I thank University of Iowa Press for allowing me to reproduce that part of Chapter 4 dealing with John Dos Passos and Chapter 6 on Whitman at the Movies, both of which appeared earlier in volumes edited by Ed Folsom, Walt Whitman: The Centennial Essays and Whitman East and West: New Contexts for Reading Walt Whitman, respectively.

To Walt Whitman, America

I returned to Whitman because he was of America, and I felt he had something to give me in terms of the American world.

The only comfort in a rather Nordic array of dispositions has been Walt Whitman. . . . He has the careless and forgiving odor of someone who will let you live.

I, too, sing America.

With a nearly desperate sense of isolation and a growing suspicion that I lived in an alien land, I took to the open road.

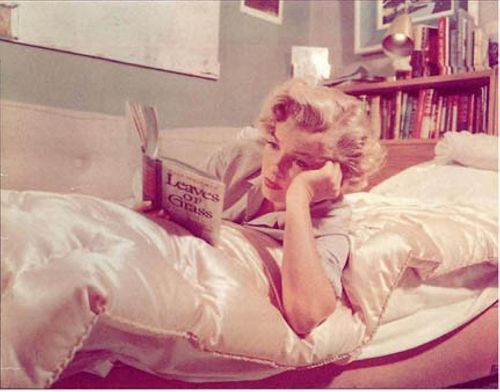

I just lifted lines from Leaves of Grass. . . . It's so American. And also his vision of a new kind of human being that was going to be formed in this country—although he never specifically said Chinese—ethnic Chinese also—I'd like to think he meant all kinds of people.

Introduction

Walt Whitman is a foundational figure in American culture.1 The inclusiveness of Leaves of Grass resonates especially powerfully in the United States, a country remarkable for its diverse population and for its ongoing struggle to fulfill its meaning and promise. Few writers continue to generate as much interest in the wider culture as the poet of Leaves of Grass. In recent years his words have been inscribed in public areas with increasing frequency: on the railing above the main terminal of Reagan National Airport, in the Archives-Navy Memorial Metro Station and in the walkway of Freedom Plaza in Washington, D.C., on the railing at the Fulton Ferry Landing at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge, at the entryway of the Monona Terrace Convention Center in Madison, Wisconsin (Frank Lloyd Wright insisted that the design should include an inscription from his favorite American poet), on a plaque at the entryway to the Willa Cather garden at my own university in Lincoln, Nebraska. Whitman was a central voice in Ken Burns's magisterial Civil War series for PBS and again for Rick Burns's PBS series on New York. He has been celebrated in musical compositions from classical to pop and invoked in political speeches, television programs, and, with remarkable frequency, films. He has been featured on postage stamps, postcards, and matchbook covers and in cartoons, including a New Yorker illustration featuring a copy of Leaves of Grass with a zipper down the spine, an allusion to President Clinton's famous gift to Monica Lewinsky. Inexpensive pocket editions of Whitman were distributed to workers and farmers during the Depression, and free copies were given to the American Armed forces during World War II. Whitman has been used to sell cigarettes, cigars, coffee (in a variety of ways), whiskey, insurance, and more. Many schools bear the name Walt Whitman, including the first private gay high school in the United States. Hotels, bridges, apartment buildings, summer camps, parks, truck stops, common rooms in guest houses, corporate centers, AIDS clinics, political think tanks, and shopping malls are named after Whitman.

Whitman's importance stretches well beyond U.S. national borders, too, of course. The recently published volume Walt Whitman and the World, edited by Gay Wilson Allen and Ed Folsom, indicates that he has had a greater impact on cultures worldwide than any writer since Shakespeare.2 Leaves of Grass has been translated into French, German, Spanish, Italian, Japanese, and Chinese, and selections of his poetry have appeared in every major language. Dozens of books on Whitman's life and poetry have been published on every continent. In his own time, Whitman was pleased when a letter from abroad reached him "sharply," addressed merely "Walt Whitman, America."3

In addition to the metonymic feat of making Leaves of Grass and his own person merge so that they became almost exchangeable terms, Whitman created similar slippage between himself and his country. Ezra Pound remarked: Whitman "is America. His crudity is an exceeding great stench, but it is America."4 Others have also conflated Whitman and America. For example, Malcolm Cowley once remarked that "before Walt Whitman America hardly existed."5 Claims of this sort are especially interesting when a racial element is added, as when June Jordan argues that "in America the father is white" and, further, that "Walt Whitman is the one white father who shares the systematic disadvantages of his heterogeneous offspring trapped inside a closet that is, in reality, as huge as the continental spread of North and South America."6 When Jordan, an African American poet, claims her place in a Whitman lineage, she savors the irony of being able simultaneously to honor him and to implicate him in the history of unwelcomed white fathering of black children. By alluding to Whitman's sexuality and the problem of the closet, Jordan touches on two major intertwined emphases of this book: Whitman's sexual legacy and his legacy for an ethnically diverse America.

There are complex issues involved when an artist of color acknowledges a white predecessor. Long before Jordan, James Weldon Johnson, Langston Hughes, and Jean Toomer all recognized the link between language and ideology, how the terminology of race divides people into repellent factions. When they acknowledged their troubled kinship with Whitman they demanded something akin to what the mulatto historically lacked: a nameable white father. Intriguingly, many Harlem Renaissance writers negotiated their positions as writers both black and American through their varying encounters with Whitman. Because Whitman's encompassing impulses start from a particular self, it is useful to recall that Whitman's very name, according to William Swinton's Rambles among Words, means "white man."7 And, in fact, however broad-minded Whitman has sometimes seemed and however liberating he has sometimes been, his primary allegiance was to a particular segment of the population, white working men. Whitman was hardly free of the racism of his culture, yet he has had an extraordinary impact on writers from disadvantaged groups. The general tendency among African American writers is to applaud and at times even revere Whitman. Still, the response has been anything but simple and uniform. For example, Ishmael Reed explores the psychic costs of an affiliation that can lead, he believes, to cultural rather than legal enslavement. For various reasons, then, including the open-endedness of Leaves of Grass and the sharply different ways that cultural project could be understood, Whitman left plenty of room for his literary progeny to reimagine America.

There is an irony of course in having Whitman, a childless man dedicated to the love of comrades, as the "father" of children of any sort, white, brown, or other. Whitman's own poetics relied heavily on passing, sometimes in a specifically racial sense, but more often through the creation of a shape-changing, identity-shifting, gender-crossing protean self at the heart of Leaves of Grass. Whitman's work invites us to consider both racial and sexual passing. Interestingly, biographers developed a Whitman myth in the early part of the twentieth century about his supposed romance with a woman in New Orleans, and even some of his close friends and disciples believed that he had fathered children. However, he was passing, occasionally pretending to be interested in women while subtly signaling his commitment to calamus love, male same-sex bonds. Sexual passing is at the heart of the poem eventually entitled "Once I Pass'd through a Populous City" in which Whitman changed the pronouns from "he" to "she" to reorient (and to disguise) his depiction of love, attachment, and loss. Whitman's fluidity of identity, his artful negotiation of the terrain at both the margin and the center, have been enabling and empowering for his followers, suggesting various ways to slip the limits of given social roles and to fashion new roles more elastic and responsive to the complexities of experience and desire.

In this study, I address various topics in light of a basic analytical premise: that Whitman is so central to practices and formulations of American culture, past and present, that we may use his life, work, ideas, and influence to examine major patterns in our culture over the last 150 years. Described broadly, some of the topics I pursue include constructions of race and authorial identity, the formation of heterosexuality and homosexuality in literature, intersections between film and literary culture, and connections between Whitman's work and different manifestations of nonconformist politics in the twentieth century. This book could have treated innumerable topics ranging from Whitman's impact on music, architecture, and the fine arts to the way his words and his image have been turned into advertising fodder. Seeking Whitman, one can find him seemingly everywhere. But rather than discussing the entire range of responses to Whitman, I dwell on case studies that illuminate how Whitman mediates understandings of race and sexuality in American culture. For me, these matters are at the heart of Whitman's legacy. I believe my eclectic approach can sketch, though it does not begin to fully portray, the poet's endlessly rich and surprising afterlife.

My opening chapter, "Whitman in Blackface" treats questions of race, region, and what the poet termed "real Americans." I investigate how Whitman crafted a poetic identity on the color line, interstitially, between racial identities. Whitman's early experiments emerged out of a working-class white culture that was fascinated by blackface performance, and he developed key elements of his poetic identity by appropriating aspects of black masculinity. I particularize Whitman's emergence and reception by being attentive to local circumstances, both Whitman's New York origins and the way in which his literary project challenged Bostonian norms for nineteenth-century literary culture. Whitman's poetry first appeared in an age of New England domination of American letters, and many early commentators rejected him on the grounds of his class, region, and sexuality. Whitman celebrated the roiling crowd and was especially fond of the working-class theater and street life in the Bowery. He set Leaves of Grass in opposition to literature conceived as conservatively exclusive. The idea that American literature was white, male, and New England-based was asserted in the leading monthlies, in collected editions, in literary histories, and in the voting for a proposed American academy of letters.8 Eventually the New England construction of literary culture crumbled as modernist writers strove to locate a more usable past. Many modernists sought a literature more responsive to a mixed people and frequently highlighted the importance of Whitman. George Santayana understood these shifting cultural currents as well as anyone, as is clear from "The Genteel Tradition in American Philosophy" and The Last Puritan (1935). Chapter 2 analyzes how Edith Wharton benefited from a newly available past. Vastly different from Whitman, Wharton found the poet nonetheless to be a central resource in both her life and art. Wharton's midlife love affair with the journalist William Morton Fullerton was conducted within a Whitmanian aura through the exchange of a copy of Leaves of Grass and the periodic invocation of the poet's language of comradeship. Fullerton was a sexually ambiguous figure who contributed in powerful (and sometimes painful) ways to Wharton's thinking about gender roles, a subject of primary importance in her novels.

D. H. Lawrence and E. M. Forster, too, found Whitman's commitment to comradeship to be of fundamental importance, as Chapter 3 indicates. Studies in Classic American Literature, Lawrence's account of American culture, culminates with a chapter on Whitman that changes radically through various versions as Lawrence struggles with the implications of male-male love. Both Lawrence and Forster address the love-death nexus, though Lawrence finally shies away from endorsing Whitmanian comradeship while Forster enthusiastically embraces the love between men in Maurice. Forster was very much aware, of course, that the "happy ending . . . that fiction allows" was at odds with the actual England he lived in, where Maurice had to be left unpublished (lest Forster be charged with supporting criminal activity). Chapter 4 considers the extreme political circumstances of the 1930s when the term comradeship often had a Marxist inflection. Here I study how John Dos Passos and Ben Shahn turn to Whitman as a democratic symbol, as a way to illuminate the dignity of ordinary work and workers, and as an antidote to the rise of international fascism. I close the chapter with Bernard Malamud's mid-century reflections on Whitman and the crises of the 1930s in "The German Refugee." Chapter 5 moves from global politics to identity politics. Here I consider Ishmael Reed, William Least Heat-Moon, and Gloria Naylor on the issue of racial and sexual passing. While Naylor and Least Heat-Moon turn to Whitman as a means of claiming a multiple racial heritage, Reed, as indicated above, sees Whitman much less favorably. In my final chapter, I explore Whitman-based movies, tracing the long engagement of cinema with Whitman from the days of Intolerance and the first avant-garde American films, through the middle of the twentieth century, and on to the last twenty years, when Whitman has been crucial for mediating our culture's understanding of same-sex love. These films offer a fresh vantage point for considering how Whitman helped create—and continues to participate in—celebrity culture.

Literary and film narratives that respond to Whitman consistently remake him in the process of trying to achieve America. 9 Whitman attempted to include, encompass, celebrate, and give voice to a variegated populace. These goals, imperfectly realized in his poetry, link his name to inclusive versions of American democracy. George Fredrickson writes of "Whitman's intellectual problem—the still unanswered question of how to give a genuine sense of community to an individualistic, egalitarian democracy."10 For many thinkers, Whitman's inclusiveness makes him crucial in efforts to build toward a harmonious American society. Nonetheless, Peter Erickson argues that Whitman does not offer a useful model for contemporary multiculturalism largely because his sympathy too often becomes appropriation. There is a way in which Whitman imposes his views on others and presupposes the rightness of his own structures and modes of perception. To some degree, Whitman can be said to be coercive. Yet if he asked readers to accede to his version of America, it was also with the belief that these very readers and writers, paradoxically, must revise him as they strive to realize themselves and remake America.

At another level, Erickson's point about multiculturalism is anachronistic. Whitman was not interested in developing multiple cultures in the United States but instead in helping to realize one culture, a complex yet unified and distinctive people. Whitman balanced his celebration of individual development with an insistence that such development could only be fully realized within the aggregate. Whitman attempted to absorb others into his expanded self and into a resulting expanded view of what might constitute his country. For Whitman, American democracy, fully responsive to a varied people, was not an achievement to be celebrated but a hope to be fulfilled: "The word democracy is a great word whose history . . . remains unwritten because that history has yet to be enacted."11

CHAPTER 1

WHITMAN IN BLACKFACE

In 1998, Toni Morrison declared that Bill Clinton was our first black president. Or at least, she clarified, he was blacker than any person who would be elected in our lifetimes. Morrison noted that he "displays almost every trope of blackness: single-parent household, born poor, working-class, saxophone-playing, McDonald's-and-junk-food-loving boy from Arkansas."2 In the ensuing controversy some wondered if Morrison's tropes themselves were not racist. The columnist Clarence Page observed, however, that many people missed Morrison's point: "Clinton knows how it feels to be an outsider and he has used that knowledge to connect emotionally and intellectually with others who felt the same way."3 This purported ability to connect may account for the steady support Clinton received from the black community despite a mixed record on racial matters. Just as Clinton knew what it was to be an outsider (and benefited from that knowledge), so, too, did Whitman, who articulated an expansive sense of community from a position both "in and out of the game."

A close look at Whitman and race reveals a complicated record. The exceptionally strong egalitarian and inclusive impulse guiding his life's work, Leaves of Grass, is periodically disrupted by moments of insensitivity and racism. These shortcomings occur both early and late in his career, and both within Leaves of Grass and outside of it. Despite these lapses, we find widespread admiration of Whitman over a long period of time and from a distinguished group of African American writers including, among others, Kelly Miller, James Weldon Johnson, Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, Richard Wright, June Jordan, Gloria Naylor, Yusef Komunyakaa, and Cornel West. A remark by William James—"a man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him and carry an image of him in their minds"—reminds us of the extent to which "Whitman" exists as an identity created nearly as much by his commentators as by the poet himself.4 On the issue of race, especially, people have partly found and partly created what they needed in Whitman based on their own dispositions and circumstances. Ronald Takaki, for example, quotes Whitman at the end of In a Different Mirror, his multicultural history of the United States, to highlight the attractive possibilities of a harmonious diversity. Notwithstanding Whitman's personal contradictions, entangled in larger cultural contradictions, he is typically remembered for his capacious and loving record of American life in all its teeming, earthy, extraordinary complexity. His work holds out the promise of renovation based on new bonds and crossings, providing a glimpse of something other than the racial separation marking so much of U.S. history (and continuing in present settings from high school cafeterias to urban neighborhoods across the country). Separatism, at times a useful means in the struggle for equality, has appeal as an ultimate goal for some multicultural theorists. But a less atomistic and essentialist goal remains vital for many, a goal based on fluid and cross-culturally enriched identities. Accordingly, many African American intellectuals have found Whitman's inclusive, future-oriented project a useful point of departure.

Whitman's cultural positioning may further explain why many African American writers have responded favorably to him. He was both privileged and not, an Anglo male but also a sexual minority, a person with roots in the working class, and a writer whose book was banned.5 African Americans have been intrigued by a poet whose reputation was significantly shaped by nineteenth-century debates, when commentary ranged from rapturous appreciation to disgusted rejection. Some nineteenth-century commentators, naive or disingenuous, mistook the persona for the person and emphasized Whitman's claim that he was rude, uneducated, lusty, and vulgar. Frequently, these commentators turned his own rhetoric against him and insisted that he was disqualified as a poet—and all the more as a national spokesman—because he was a sexual, religious, and even subhuman outsider. They described Whitman as bestial, judged him to be insane, suggested that he should commit suicide, urged that he be publicly whipped, called him a "satyr," and tarred him as "Caliban," Prospero's half-human slave, son of the witch Sycorax and a devil and symbol of base and lustful urges.6 They employed an array of tropes to depict him as an outsider in his own land. They made him, as it were, black.

THE SPACE BETWEEN MASTERS AND SLAVES

Whitman began his career at a time when many white performers were appearing in blackface, some of whom the poet himself witnessed. Nineteenth-century commentators, disturbed by Whitman's violation of codes of gentility, strove to further tar him by associating him with black men and with widely popular New York minstrel shows.7 Some of their descriptions of Whitman amounted to caricature, but they could claim that they took their cue from the poet himself, who repeatedly explored cross-racial identifications.

Occasionally Whitman asserted these racial crossings directly, as when he declares, in the initial poem of Leaves of Grass (1855), "I am the hounded slave," and at other times the crossings were made more indirectly. Whitman's cross-racial identifications are important in two primary ways. First, these racial crossings illustrate how Whitman, as was common in working-class antebellum white male culture, constructed a sense of manhood partly through appropriating black masculinity.8 Eric Lott has noted that such appropriations of black masculinity typically involved a complex mixture of both admiration and fear, of both yearning toward and warding off, and of both love and loathing.9 Second, Whitman's racial crossings enable us to situate his work within a rhetorical field significantly shaped by the approach of middle-class white abolitionists to the question of race. Whitman, rarely radical in his antislavery positions, nonetheless shared with these abolitionists a reliance on sympathy in addressing racial slavery.

Whitman was at his most progressive in the years leading up to 1855 and somewhat more conservative thereafter, though unevenly and unpredictably so. He was more daring on racial issues in his manuscripts than in more polished work, as jottings and drafts from approximately 1850-56 reveal. This material was unknown to African Americans in the nineteenth century and remains inadequately studied even today, but I focus on these manuscripts because they help highlight and explain some contradictory elements in Whitman's better known works and because they clarify his overall thought and the forces shaping it.

In composing the first two editions of Leaves, Whitman made clear that he regarded racial slavery as a fundamental threat to what he perceived as the country's historical mission to promote freedom and equality. The poet who once penned the motto "No nation once fully enslaved ever fully recovered its liberty" recognized the ideologically contradictory position of the United States as a slave- owning democracy.10 Despite this perception, his commitment to freedom was stronger than his commitment to equality across ethnic and racial lines. Given his national poetic ambitions, it is not surprising that slavery and freedom reside together in Leaves of Grass, uneasily enmeshed, at the heart of things.11

In one of his earliest notebooks, "Talbot Wilson"—long thought to date from 1847 but now understood to be from about 1854—Whitman broke into free verse in the manner of Leaves of Grass.12 After asserting that he is the poet of the masters and the poet of the slaves, he projects himself into the highly charged space between masters and slaves, both dangerous and erotic:

I am the poet of slaves,

and of the masters of slaves

I am the poet of the body

And I am

I am the poet of the body

And I am the poet of the soul

The I go with the slaves of the earthare mine, andequally with

the equally with the masters areequallymine

And I will stand between

the masters and the slaves,

And I eEntering into bothand

so that both shall understand

me alike.

Whitman occupies and transforms the cultural space of violation. He underscored the stakes at issue in another notebook from this period: "what real Americans can be made out of slaves? What real Americans can be made out of the masters of slaves?"14 Whitman's idea of America, a goal rather than an achieved condition, was based on an inclusive and exalted commonality, the "divine average." Masters and slaves were ill-suited to this notion of America not because of whiteness or blackness but because of the polarized qualities—despotism and debasement, authority and dependence—characteristic of slavery itself. In his notebook lines, Whitman seeks to enter slave and master to identify with them, to grasp their meaning and circumstances. Convinced of the inseparability of the body and the body politic, and attempting to offset the effects of rape and the white fathering of property on enslaved women, Whitman strives to remake penetration as a vehicle for purification. His metaphor conveys suggestions of both transgression and transformation, preparing us for the twist at the end: the result of Whitman entering others is not his understanding of them but their understanding of him. The insistence that master and slave should adopt his view can be regarded as imperious arrogance. But if we merely scold Whitman for presumptuousness we may miss a key point. At a time when abolitionists were deeply committed to intersubjectivity and described it as a white mobility as opposed to black stasis, Whitman grants the power of identification to both master and slave. This is extremely unusual for the antebellum period, when sympathetic mobility was reserved as a particular racial privilege as white abolitionists sought to establish rich human inwardness through flirtations with inward merging. Typically, a corresponding ability was not granted to black subjects. In abolitionist literature it is the white sympathetic onlooker who is inwardly transformed, not—as Whitman has it—both white and black, both slave and master.15

Despite the key passage above granting black subjects sympathetic mobility, Whitman's more common approach was to explore white racial crossing. The "Talbot Wilson" notebook, recently recovered by the Library of Congress after being missing for decades, deserves extensive quotation because, in the flickering, not quite visible movement between its leaves, we can sense the birth of Whitman's poetic sensibility. At the opening of a sequence of passages that contribute to the first published version of "The Sleepers," Whitman indulges in a male fantasy of size and plenitude.

I held more than I thoughtI did not think I was bigenough for so much exstasyOr that a touch couldtake it all out of me.

This unpromising mixture of wishfulness and bravado is suddenly recognized as something extraordinary when read in conjunction with what follows. That is, this male fantasy is associated culturally and psychologically with the succeeding notebook leaf, treating black rage, revenge, and empowerment. On that succeeding leaf, Whitman launches into a speech in the slave's voice, though readers may hear Whitman, the slave, or both of them. Importantly, in this notebook Whitman links across two leaves a dream of great virility and the release of a black voice:

I am a curse:

Sharper thanwindserpent's

eyes or wind of the ice-fields!

O topple downlikeCurse!

topple more heavy than

death!

I am lurid with rage!

I invoke Revenge to assist

me—

The reviewer of the first edition of Leaves who associated Whitman with Caliban could not have known about this notebook in which Whitman seems to build on Caliban's famous complaint to Miranda: "You taught me language; and my profit on 't / Is I know how to curse."18 Caliban, an enslaved victim of imperialism, waged a rebellion in response. Whitman's notebook articulates, in the highly charged context of the 1850s, the desire for black revenge and rebellion. We are not presented with the pathetic and victimized black of much antislavery—yet typically racist—literature. Instead Whitman depicts an enormous force, power, and submerged anger in his black speaker.

In the following notebook passage, Whitman yearns for slaveholders to be punished with sexual and reproductive rot:

Let fate pursue themI do not know any horrorthat is dreadful enoughfor them—What is the worst whipyou haveMay thegenitalsthatbegat them rotMay the womb that begat

Whitman's concern with genitals was anything but arbitrary. In the South and elsewhere in the United States, black men were castrated—sometimes literally, sometimes psychologically—so as to keep them at a distance from white women. Meanwhile some white men raped and impregnated their slave women, thus adding to their holdings in property. Whitman responded by creating a black speaker of potent force. The slaveholders, with whips raised against them by the poet and their sexual license turned into sexual corruption, will be pursued even beyond death. Whitman says he will not listen or offer mercy, the grave will offer no hiding place, and even the "lappets of God shall not protect them."20 And then we encounter a stunning transformation, as curious as it is complete:

The sepulchreThe sepulchre and the whiteserving the shroudlinen have yielded me upObserving the summer grass

This notebook announces profoundly transformative effects yet comes to rest in passivity, a result some may regard as mere acquiescence. Yet out of this strange brew of sexual potency and sexual rot, oppression and punishment, racial crossing and resurrection, a poet emerges, absorbing the lessons of the grass, which he will famously describe as a "uniform hieroglyphic" that grows "among black folks as among white." This was an insight that provided the central image for Leaves of Grass, and Whitman's notebooks allow us to see in what political ferment the image was born.22

In a manuscript related to this notebook, a tangled draft now held at the University of Virginia, Whitman articulates more fully than in any published version of "The Sleepers" the plight of a particular "slave negro" and his bold response. Whitman's deletion of "slave" in favor of "negro" in this context shifts the emphasis from bondage to race:

I amblacka curse: ablack slavenegrospokefelt thoughtthinks me

You YouHecannot speak foryourhimself,slave,negro—I lendyouhim

my ownmouthtongue

A black[illegible]I dartedlike a snake from[his[?]]^[your[?]]

mouth.——

IMy eyes are bloodshot, they look down the river,

A steamboatcarries offpaddles away my woman and children.——

[previous two lines canceled with vertical lines]

Around my neck I am

T TheHisIron necklace and the red sores ofmythe shoulders

I do notfeelmind,

TheHoppleand ballatmythe ancles, ^and tight cuffs at the wristsdoes

^must not detain me

I ^willgo down the river with ^the sight of my bloodshot eyes,

Iwillgoonto the steamboat that paddles ^offmywifewoman and child

AI do not stop with my wom[an?] and children,

I burstdownthe saloon doors and crash on [?]

party of passengers.——

But for them, I am too should have been on the steambo[at?——page

cut off]

I should soon

Toni Morrison has argued that, for whites, the experience of selfhood and freedom is grounded in racial difference and inequality, and certainly Whitman's exploration of identity on the color line is partially self-exploration.24 The bursting of the saloon doors by the "slave negro" is closely related to Whitman's description of himself in "Song of Myself": "Unscrew the locks from the doors! / Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!"25 Whitman acts on his own exhortation and achieves himself through this bold black man. It is possible to regard Whitman's lines as solipsistic and to conclude that his self-exploration is self-misrecognition. But the lines are more interesting and more politically charged if we see them as breaching the very borders of identity. Significantly, they raise the prospect of violence and of this "slave negro"'s assertive efforts to establish justice and freedom. Intriguingly, Whitman uses the word "lend," indicating that he does not strive to appropriate the black voice but to enable it, to aid the slave/himself in locating a tongue with the lethal power of a snake. Whitman says that the bestowal of power goes from white to black, even though we witness a mutual exchange and enhancement. For Whitman, "lending" is also borrowing as he appropriates black masculinity to develop his poetic persona. He has freed no slave, taken no part in action on the Underground Railroad.26 Yet despite the racism in his city and social class, he has made an important intellectual and empathetic breakthrough. He offers one of the first attempts by a white author to narrate through a black voice and provides a compelling illustration of the power of racial crossing in the making of a complex intellectual identity. No doubt it was the egalitarian, boundary-crossing side of Whitman, especially evident in the manuscripts but also apparent in the first two published editions of Leaves of Grass, that recommended his work to the radical abolitionist publishers, Thayer and Eldridge of Boston, publishers of the third edition.

In the writings of abolitionists, racial crossing frequently moved along a circuit of pain.27 Whitman, too, used pain to achieve identification, but as he moved closer to the publication of the untitled 1855 version of "The Sleepers," he deleted the references to "red sores" on the shoulders, the "Hopple" at the ankles, and tight cuffs, perhaps because he recognized that the spectacle of pain too often became pornographic.28 By the time of the first edition of Leaves he had lessened the emphasis on physical pain and chosen to create not a pitiable but a powerful individual, an heir of Lucifer, the arch rebel:

Now Lucifer was not dead . . . . or if he was I am his sorrowful terrible

heir;

I have been wronged . . . . I am oppressed . . . . I hate him that

oppresses me,

I will either destroy him, or he shall release me.

Damn him! how he does defile me,

How he informs against my brother and sister and takes pay for their

blood,

How he laughs when I look down the bend after the steamboat that

carries away my woman.

Now the vast dusk bulk that is the whale's bulk . . . . it seems mine,

Warily, sportsman! though I lie so sleepy and sluggish, my tap is

death.

As Ed Folsom notes, Whitman admires Lucifer, a figure brave enough to confront even a divine master.30 At a time when slaves routinely were either degraded or pitied, Whitman emphasizes the divinity of Lucifer in related manuscripts. (In "Pictures," another formative early poem, Whitman had explicitly linked a black Lucifer to revolt.31 ) Christopher Castiglia describes typical black representations as emphasizing "traits of piety, nurturance, and conjugal fidelity threatened by the outrages of slavery."32 In depicting Black Lucifer, Whitman adheres to the pattern of "conjugal fidelity"—in fact, he boldly insists on black male sexual possessiveness at a time when white masters often threatened the sexual dynamic and integrity within black families. With equal daring, Whitman diverges from the idea of an ordinary piety and from stereotypical white paternalism and black male submission. Whitman has his Black Lucifer likening himself to a (sperm?) whale and making clear that he is a potent force to be reckoned with.

The poet insisted that blacks were destined to reach a high estate: "Where others see a slave a pariah an emptier of privies the Poet beholds what when the days of the soul are accomplished shall be peer of God."33 Whitman recurrently returns to the idea of a semi-divine origin and semi-divine destiny for blacks. But the middle ground is usually missing when he treats blacks. That is, his tendency is to exalt noble black people in the distant past and distant future and to think of blacks in the present as less than fully equal human beings. Over the long publishing life of Leaves (beginning eight years before the Emancipation Proclamation and ending nearly three decades after it), Whitman typically does not depict blacks as ordinary people, common Americans. Clearly, the social landscape that shaped Whitman had marked blacks as distinctive. With "slave negro"—his visibly uncertain term from the "I am a curse" manuscript—Whitman struggled with terminological slippage as he referred to categories that overlapped but did not match. We recall that Whitman doubted that "real Americans" could be made out of slaves, a defensible position for a committed democrat. But this position becomes insupportable when "slave" and "negro" become blurred. Whitman's blind spot was in his inability to envision or his unwillingness to promote the right of blacks to full citizenship, an unwillingness that becomes most clear in the postwar years.34

This shortcoming partially undermines one of the otherwise bracing and effective poems of 1855, the untitled work now known as "I Sing the Body Electric." Whitman once planned to put "I Sing the Body Electric" in the final position for the 1855 Leaves (he referred to the poem, in notes to himself, as "Blacks").35 In one section of the poem, Whitman dramatizes his encounter with an enslaved black man on the auction block, in whom he sees "the start of populous states and rich republics." Yet even in recognizing the capacity of blacks for self-government, Whitman significantly mentions "republics" rather than the American Republic, and thus avoids contemplating black involvement in U.S. political decision making. (Interestingly, Whitman used "republics" only twice in the poetry of the 1855 Leaves, and the other usage connects the black man with himself in striking fashion since both are said to start republics: in the opening poem, he says "this day I am jetting the stuff of far more arrogant republics.") Although Whitman repeatedly identifies himself with blacks in ways both obvious and subtle, he is more comfortable with blacks participating in remote "rich republics" of the future than in the next election in the United States.36

In the context of cross-racial masquerade and ventriloquism, one of the most intriguing sections of the poem treats a stalwart old man.

The shape of his head, the richness and breadth of his manners, thepale yellow and white of his hair and beard, the immeasurablemeaning of his black eyes,These I used to go and visit him to see . . . . He was wise also,He was six feet tall . . . . he was over eighty years old . . . . his sonswere massive clean bearded tanfaced and handsome,They and his daughters loved him . . . all who saw him loved him . . .they did not love him by allowance . . . they loved him withpersonal love;He drank water only . . . . the blood showed like scarlet through theclear brown skin of his face.

Perhaps this old man is white because no one tells us so and because, as Toni Morrison argues, the default in American culture is white. Yet he also has "black eyes" and "blood" that showed through the "clear brown skin of his face," phrasing that becomes even more noteworthy in 1860 when Whitman added a hyphen to describe the face as "clear-brown." The tension between clarity and ambiguity is fascinating here, especially since the poem culminates in a question underscoring the ultimate uncertainty of all racial lineages: "Who might you find you have come from yourself if you could trace back through the centuries?"38

In this same poem, Whitman's description of slaves at auction, grounded in his experiences in 1848 in New Orleans where slaves were sold within an easy walk of his lodgings, illustrates not only the power and limits of sympathy but also the awakening of his powerful commitment to adhesiveness. Whitman uses the black body to unfetter homoeroticism. His approach differs from that of minstrel shows that periodically invoked homoeroticism only to later circumscribe and contain it.39 Jay Grossman notes that the slave auction offered a rare instance of the nineteenth-century naked body on display, a staging of the body open to the most intrusive examination.40 Whitman transformed the slave auction into an occasion to articulate and to love the body, indexing its glories from top to toe. Whitman's imagining of the black body advanced—perhaps even enabled—his overall treatment of sex and the body in Leaves of Grass. "I Sing the Body Electric" is critical for Whitman as a poet of intimacy and eroticism. In 1856 he added the remarkable section enumerating parts of the human body that ended the poem in all subsequent versions. In 1860 he provided a gloss on the poem by placing just before it "Enfans d'Adam 2" (later titled "From Pent-up Aching Rivers") a poem that clearly comments on the auction and the powerful and unsettling erotics of that spectacle:

The welcome nearness—the sight of the perfect body,The swimmer swimming naked in the bath, or motionless on his backlying and floating,The female form approaching—I, pensive, love-flesh tremulous,aching;The slave's body for sale—I, sternly, with harsh voice, auctioneering,The divine list, for myself or you, for any one, making,The face—the limbs—the index from head to foot, and what itarouses,The mystic deliria—the madness amorous—the utter abandonment,(Hark, close and still, what I now whisper to you,I love you—O you entirely possess me.

It is not accidental that Whitman yokes together the "slave's body for sale" and mention of the "divine list" that lovingly itemized body parts from toe-joints to heart-valves, from arm-pits to nipples, from man-root to womb. Despite the poet's striking distinctiveness, he follows a well-known cultural pattern in overcoming white inhibitions and prohibitions about sex and corporeality through recourse to the captive body and the racial other.42 Race, sexuality, domination, and subordination are entangled here. Whitman's erotics are released not only by black bodies but also by the very hierarchy of slavery. Whitman and white sexuality are liberated even as the slave remains enchained.

Intriguingly, the word "possess" turns the last of these lines in an unexpected way, with Whitman, rather than the slave "possessed"—and in multiple ways.43

At the end of "From Pent-up Aching Rivers," possession itself is reversed by desire for the body, and the possessor becomes possessed. The reversal is important because in the slippage from master to slave, slave to master, hierarchy is undone, and eventually the terms themselves erode. Whitman's use of "possession," connected here to ownership and bondage, is part of his metaphoric use of slavery. Enslavement for Whitman in 1855 was a complex metaphor central to his initial articulation of Leaves. He once remarked: "Every man who claims or takes the power to own another man as his property, stabs me in that the heart of my own rights." To own people was to violate what Whitman saw as the "primal right—the first-born, deepest, broadest right—the right of every human being to his personal self."44

But, in a different context, Whitman also said: "What is it to own any thing?—It is to incorporate it into yourself, as the primal god swallowed the five immortal offspring of Rhea, and accumulated to his life and knowledge and strength all that would have grown in them.—."45

His way of knowing risked the very mastery he both abhorred as a social reality yet needed as a poetic force. Thus, though he found the roles of both masters and slaves repugnant, he reacted in typically complicated and fascinating ways, finding mastery and utter dependence powerful tropes. His famous open letter to Emerson of 1856 is a dramatic case in point, which I have elsewhere discussed in terms of a master-slave relationship.46

Whitman could imagine himself becoming a slave in the sense of giving himself over to a project, to his muse, to inspiration, to the war effort. Regarding his hospital service, for example, he told Horace Traubel: "What did I get? Well—I got the boys, for one thing. . . . I gave myself for them: myself: I got the boys: then I got Leaves of Grass." His work with soldiers became his "religion," his "lodestar." It was his "master," and, as he said, it "seized upon me, made me its servant, slave."47

ENTHRALLED AND ENTANGLED: THE TRAPPER'S BRIDE, THE RUNAWAY SLAVE, AND THE TWENTY-NINTH BATHER

The centrality of slavery to Whitman's thinking can be illuminated if we take a close look at three consecutive passages in the initial poem of the 1855 Leaves (the untitled poem now known as "Song of Myself"). Interestingly, when Whitman produces his first developed characters in his book—respectively, the trapper and his bride, the fugitive slave, and the twenty-ninth bather—he links them through a consideration of bondage. He examines the way bondage connects with sexuality, romance, economics, domestic intimacy, and marriage. As both an actuality and a trope, bondage offered Whitman a means of emphasizing commonalities that cut across gender, race, and circumstance.

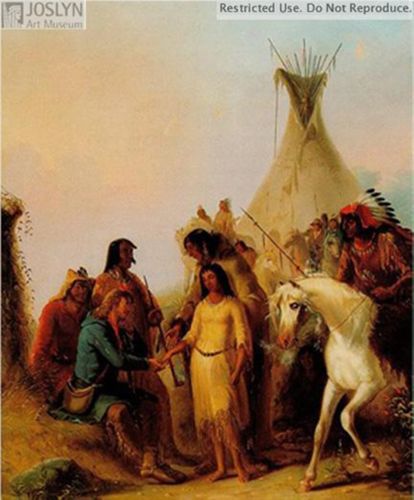

The first of these tightly clustered scenes was prompted by The Trapper's Bride, the work of the Baltimore artist Alfred Jacob Miller.48 Existing in multiple versions in both oil and watercolor, The Trapper's Bride records an event Miller witnessed during a trip West from near present-day Kansas City, Missouri, to Fort Laramie, Wyoming, in 1837. Miller had been commissioned by an adventurous Scotsman, Captain William Drummond Stewart, to accompany him and to "sketch the remarkable scenery and incidents of the journey."49 In effect, Miller was to provide souvenir sketches of the American West. After their trip, Miller accompanied Stewart back to Scotland for eighteen months where he reworked some of his prairie sketches into full-scale oils for Stewart's ancestral home, Murthly Castle. Peter Hassrick comments on the aura of Miller's works: "His characters, whether trappers or Indians, seemed suspended in idyllic haze."50 This result was achieved partly through the intervention of Stewart, who made Miller alter any Indian without "sufficient dignity in expression and carriage."51

Although Miller was willing to bestow admirable physical qualities on Indians, his overall opinion remained uncompromisingly harsh: he held that an Indian "uses every stratagem, fair and foul, to preserve . . . [his] worthless life."52 Ultimately, Miller's painterly eye and hand were better than his extensive commentary on his own work. Dawn Glanz argues that The Trapper's Bride depicts "an Indian ceremony, taking place on Indian soil . . . beyond the jurisdiction of the white man's laws, customs, and traditions."53 But of course the view of the ceremony, and the resulting painting and commentary, were not beyond Miller's personal jurisdiction and, like all of his work, should be considered in light of his equal mix of admiration and loathing of Indians. Because of a lack of both knowledge and sympathy, Miller failed to accept on its own terms the common tribal practice of gift exchange at the time of marriage, and thus he found marriage conducted au facon du pays to be debased. He misunderstood the custom of the country, which typically involved the man paying bridewealth to the woman's family,54 and when he witnessed the event recorded in The Trapper's Bride, he concluded that he was encountering de facto prostitution or slavery. He spoke of the "price of acquisition . . . $600 paid for in the legal tender of this region: viz: Guns, $100 each, Blankets $40 each, Red Flannel $20 pr. yard, Alcohol $64 pr. Gal., Tobacco, Beads &c. at corresponding rates."55 One assumes that Miller would not have found anything amiss in a European woman providing a dowry to the groom's family. His inability to see beyond his own cultural norms was common to many nineteenth-century Euro-Americans who mistakenly assumed that the marriage customs of tribal peoples were tantamount to practices of slavery.56

Glanz and Joan Troccoli have argued that The Trapper's Bride is an emblem of "the Jeffersonian ideal of a peaceful amalgamation of the races" and the "hope of reconciliation between civilization and the wilderness."57 Superficial aspects of the trapper's Anglo appearance have led these and other critics to assume that Miller's painting portrays the marriage between a white man and an Indian maiden.58 But the trapper is by no means unambiguously white. Trappers were in fact bicultural or liminal figures and were often regarded in the nineteenth century as "White Indians."59 Equally to the point, Miller himself had difficulty categorizing the particular trapper he depicted in The Trapper's Bride: "A Free Trapper (white or half-breed) . . . is a most desirable match" (see fig. 1).60

The figure of the bride is also complex, though in a different way, because she (paradoxically) appears to be chaste and carnal at once. Small, innocent, almost childlike, she is dressed in white and sharply distinguished from the half-nude Indian woman in red who appears in Miller's 1845 and 1846 renditions of the scene (see fig. 2). Yet if Miller distinguishes the bride from this obvious sexual temptress, he makes the bride, too, sexually suggestive in less obvious ways. For example, the artist depicts her in such a way that her pelvis juts forward, and her white dress hugs and highlights the contours of her body. Miller probably intended her bare feet to be erotic also. His patron, Stewart, is known to have been attracted to the bare feet of young native women.61

Figure 1.

Alfred Jacob Miller, The Trapper's Bride, 1850, oil on canvas. Courtesy Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska.

Figure 1.

Alfred Jacob Miller, The Trapper's Bride, 1850, oil on canvas. Courtesy Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska.

Figure 2.

Alfred Jacob Miller, The Trapper's Bride, 1845, oil on canvas. Courtesy Eiteljorg Museum of American Indian and Western Art.

Figure 2.

Alfred Jacob Miller, The Trapper's Bride, 1845, oil on canvas. Courtesy Eiteljorg Museum of American Indian and Western Art.

Whitman also underscores the erotic appeal of the Indian bride, though he instead emphasizes her "voluptuous" nature and the length of her hair, which reaches her feet. (In none of Miller's versions—or at least in none of the five different versions I have seen—does the bride possess the statuesque build associated with voluptuousness, nor does she have the extraordinary profusion of hair that Whitman gives her.) Edgeley W. Todd, one of the first to comment on how The Trapper's Bride figures in "Song of Myself," was misleading, then, when he argued that Whitman provides "simply a verbal translation of what he saw in the painting," and that "not a single detail in the poem is without its counterpart there."62 Subsequent critics have also failed to examine how Whitman purposefully veers away from Miller. Perhaps the most significant difference between painter and poet is that Miller masks conflict while Whitman explores it. That is, in Miller's depictions the trapper's rifle might as well be a staff given the meek, pacific, and longing expressions of the trapper and his friend. Yusef Komunyakaa, in a poem about the 1846 version of Miller's work, aptly describes the two men as sitting "like Jesus / & a shepherd in rawhide."63 In contrast, in Whitman's lines, the rifle plays a much more threatening role. Unlike Miller, Whitman records a troubling scene, one that conveys a sense of the uneasy, conflicted, and destructive aspects of the contact of cultures:

I saw the marriage of the trapper in the open air in the far-west . . . .the bride was a red girl,Her father and his friends sat near by crosslegged and dumblysmoking . . . . they had moccasins to their feet and large thickblankets hanging from their shoulders;On a bank lounged the trapper . . . . he was dressed mostly in skins. . . . his luxuriant beard and curls protected his neck,One hand rested on his rifle . . . . the other hand held firmly the wristof the red girl,She had long eyelashes . . . . her head was bare. . . . her coarse straightlocks descended upon her voluptuous limbs and reached to herfeet.

Here the trapper holds his bride as if she were recently captured rather than recently wedded. The idea that the trapper "held firmly the wrist of the red girl" is Whitman's own invention—Miller's renderings of the scene do not show this type of grasp. The poet's phrasing describes a coercive relationship, which conveys a truth about the imperial nature of western expansion and the role of trappers as one of the first in a series of forces that ultimately "demoralized, depopulated, and eventually dispossessed Indian people in the trans-Mississippi West."65 In Whitman's lines, the trapper "lounged," an informal posture at odds with the rapt attention of the trapper in all of Miller's versions of The Trapper's Bride. There is a striking incongruity between "lounged" and "held firmly" because the relaxation implied by the one is at odds with the exertion required by the other. Whitman's trapper strikes a pose of confidence in an encounter fraught with anxiety. Even the description of the trapper's curls hints at danger: his neck needs to be "protected."66

Whitman juxtaposes the account of the trapper and his bride with his treatment of the runaway slave. The scenes are related both through theme and imagery, including a "rifle" that is an important element in both scenes. Both passages also emphasize bare feet: we recall that the bride's hair reached to her feet, and Whitman describes himself as tending the black man's feet.

The runaway slave came to my house and stopped outside,I heard his motions crackling the twigs of the woodpile,Through the swung half-door of the kitchen I saw him limpsey andweak,And went where he sat on a log, and led him in and assured him,And brought water and filled a tub for his sweated body and bruisedfeet,And gave him a room that entered from my own, and gave him somecoarse clean clothes,And remember perfectly well his revolving eyes and his awkwardness,And remember putting plasters on the galls of his neck and ankles;He staid with me a week before he was recuperated and passed north,I had him sit next me at table . . . . my firelock leaned in the corner.

Earlier in the poem, we have been prepared to think of feet in connection with acts of intimacy by the famous union of body and soul in which the totality of sexual engagement is underscored by the line: "And reached till you felt my beard, and reached till you held my feet." The runaway slave, with his awkwardness and revolving eyes, may seem an unlikely focus of erotic interest, though the reference to the opening to the speaker's own room is worth noting. In addition, the most tender touch—actual as opposed to fantasized—described in Whitman's sequence of bondage scenes is between the speaker and the runaway. Soon after these scenes, a black drayman enters the poem, and he is sharply contrasted with the runaway. With his "polish'd and perfect limbs," the black drayman clearly is a person with great appeal for the speaker: he fits into a pattern of streetcar and train conductors whom Whitman found especially fascinating. The poet makes a before-and-after statement by replacing the runaway slave with the black drayman, or, if you will, metamorphosing the one into the other through the power of freedom and Whitman's baptismal bath.68 No longer driven by hounds as was the runaway, the drayman is himself a driver. One index to the transformation is in the contrast between the "revolving eyes" of the runaway and the "calm and commanding glance" of the drayman.

The third of these scenes of bondage involves Whitman's famous twenty-ninth bather, a wealthy woman confined behind the windows of her house, yearning for the freedom enjoyed by the naked bodies she sees cavorting in the water. Significantly, she sees "white bellies" bulging to the sun, luxuriating in a race- and gender-based relative freedom. The twenty-ninth bather experiences what women's rights advocates sometimes called "the slavery of sex" and is imprisoned and confined by the codes of her time.69 As Vivian Pollak notes, she "owns" the fine house but does not own herself.70 Like the trapper, she is situated on a "bank." The woman also shares with the trapper a number of paradoxically empowering traits. The elevated position of both reinforces their more privileged social standing. Both the trapper and the twenty-ninth bather are bolstered by finances. Both are situated on a "bank," a word that, when enunciated, calls to mind the alternative meaning of financial institution. Both senses of the word are relevant here given the wealth of both the trapper and the twenty-ninth bather relative to their partners. The twenty-ninth bather passage is notable for its breaking of bounds, its violation of decorum, its acknowledgement of female sexuality, and its acceptance of voyeurism and nonprocreative sexuality. But there are notable effects of hierarchy at work, too, not only based on wealth but also on knowledge, because she can gaze at the men bathing and know them, while they remain unaware of her. Liberation and equality are available only in her remarkable fantasy. Indeed, in all three scenes, Whitman pursues erotic fantasy as an antidote to slavery. More practically, Whitman's lines on the runaway slave also prefigure his later role as the devoted comforter of wounded Civil War soldiers to whom he provided sustaining aid, hope, and love, serving black and white alike.

As we will see in the next chapter, focusing on Edith Wharton, Whitman's promised liberation could also be limiting for women. We might think of Wharton as a sister of sorts to the twenty-ninth bather, the wealthy woman who yearns to escape the confining mores of her time and place, who seeks a greater sexual freedom and expressiveness, and who believes she finds it in a group of men drawn to comradeship. Interestingly, the twenty-ninth bather passage ignores the very problem Wharton will explore: what happens to the woman who wants to follow Whitman's recommended trajectory away from the stifling prison of class privilege and into the physical release of passion, touch, and camaraderie when she comes to realize that what she has entered is not a scene of heterosexual passion, but a scene of male-male liberating touch? These young men do not even know the lady is there among them, and, even if they did, would they care? If she were really there, would they all turn toward her, or would they take a look, then turn back toward each other? Whitman's poem doesn't probe these questions, but they are precisely what Wharton does probe.

TRACKING WHITMAN IN BOSTON AND THE BOWERY

Early reviewers not only described Whitman as like "Caliban" but as the "Bowery Bhoy in Literature." In the antebellum period the Bowery had been a locale for minstrelsy, among other entertainments. To hang the label of the "Bowery" on Whitman was to do more than suggest a lack of racial purity on his part. The epithet suggested a broad-reaching contamination: commentators who mentioned the Bowery did so to condemn Whitman through association with immigrant groups, moral degeneracy, and working-class culture. In the postbellum period, when the Bowery became more seedy, commentators continued to insist on Whitman's association with this prominent street. For example, in 1882, the New York Examiner described Whitman as "the 'Bowery Bhoy' in literature, a rowdy with . . . the itch for writing. . . . He could not have been bred anywhere but in a certain part of New York city a generation ago—in any other place or at another time he could no more have been developed than Plymouth Rocks can be hatched out of cobble-stones."71 It is intriguing that a New York paper would criticize Whitman in terms that underscored Plymouth Rock, a national symbol but also very much a symbol of regional rival New England. When this commentator and others cited Whitman's ties to New York's Bowery, they linked him to a particular geographical space that served as a trope for a moral condition. Whitman, however, was not inclined to disown the Bowery: he noted that the scale of the Bowery is "conventionally lower" than in Broadway, "but it is more pungent. Things are in their working-day clothes, more democratic, with a broader, jauntier swing, and in a more direct contact with vulgar life."72 Dotted with theaters, the Bowery was known for its sexualized street life throughout the nineteenth century. Race and ethnicity are regularly interwoven with sexuality in constructions of Whitman, with circular reasoning holding that the racial and ethnic other was oversexed and because Whitman was oversexed, he himself was the other. Whitman wished to be the poet of both Broadway and the Bowery, but it was his celebration of the Bowery that offended that powerful group of people who wanted a literature constructed according to the gentlemanly dictates of the Boston Brahmins. Those who labeled him a Bowery boy attempted to relegate him to a particular regional and class niche.73

The final part of this chapter addresses the question of Whitman and blackface from a broader perspective by considering the Boston-New York contrast and the shifting way in which competing versions of literary culture operated in conjunction with issues of race and class. Whitman attempted to make himself "the age transfigured," to "flood himself with the immediate age as with vast oceanic tides."74 Taking on various hues and identities (and frequently risking the danger of taking over these identities), Whitman worked in a way somewhat akin to a blackface performer as he disrupted genteel expectations and crossed gender and racial lines. In other important ways, however, he was revising the form of blackface performance itself since his ultimate goal was to unsettle and defamiliarize existing identities and to make visible and audible all aspects of a multifaceted and multiracial society. For him, fluidity and receptiveness were requirements of national realization.

Ironically, though Whitman himself had been eager to set the terms and conditions of American identity ("What real Americans . . . ?"), he had his own national credentials questioned by those dedicated to a New England- and Anglo-Saxon-centered view of American culture. One literary history, coauthored by Barrett Wendell and Chester Noyes Greenough, observed that "[Whitman's] democracy . . . is the least native which has ever found voice in our country."75 George Woodberry claimed: "A poet in whom a whole nation declines to find its likeness cannot be regarded as representative."76 Barrett Wendell complained in his Literary History of America that Whitman's violation of traditional standards and values resulted from his being "of the artisan class in a region close to the most considerable and corrupt centre of population on his native continent," no doubt meaning New York.77 Wendell, whose wife, Edith Greenough Wendell, served as president of the Colonial Dames' Plymouth Executive Committee,78 did not hesitate to declare that Whitman was "less American than any other of our conspicuous writers."79

In response to great waves of immigration that occurred between 1880 and 1920, the so-called Brahmins had become ever more insistent about a particular perspective on American culture, asserting that the real, pure, or true Americans were Anglo-Saxons. The great migrations coincided with the founding of such groups as the Society of Mayflower Descendants and the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution. The migrations also coincided with the efforts of publishers who commissioned numerous professors (almost all from New England) to write literary histories for high school and college use with the hope of unifying the heterogeneous American people under the "aegis of New England" by fashioning a national history anchored in that region. Nina Baym has noted that "conservative New England leaders knew all too well that the nation was an artifice and that no single national character undergirded it. And they insisted passionately . . . [on] instilling in all citizens those traits that they thought necessary for the future: self-reliance, self-control, and acceptance of hierarchy."80 These New England histories of American literature claimed that the inclusive Whitman was un-American because of his supposed lack of moral earnestness and because he had failed to gain any popular following whatsoever. The poet was steadfastly opposed by those who, far from being interested in exploring blackface, strove to whitewash American culture.

If we look in more detail at how one prominent New Englander, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, responded to Whitman, we can study an especially vivid and illuminating case of increasing Boston conservatism. In the antebellum period, Thomas Wentworth Higginson and other Bostonians had been more radical than Whitman in their support of abolition, being willing to resort to violence to aid blacks, as in the case involving the fugitive slave Anthony Burns. But by the 1880s Higginson's growing conservatism was in fact part of a significant New England pattern of retreat.81 Higginson was now ready to defend the disenfranchisement of blacks if it would help bring about sectional reconciliation. He was also adamant about attacking Whitman in a series of essays from 1881-98. In the closing decades of the century, the roles of Whitman and Higginson reversed, at least in so far as image and cultural meaning were concerned. Whitman, less radical in the 1850s in the face of the slavery crisis than many Boston intellectuals, had become by the 1880s increasingly associated with the teeming masses, the immigrants, the downtrodden of all types. Meanwhile some of the same Boston intellectuals who had led the charge for the emancipation of blacks had come to be associated with propriety, exclusiveness, and backsliding on racial issues.

There was some hypocrisy mixed in with prudery that manifested itself in Higginson's uneasiness over Whitman's sexual bravado. Whitman's sexual explicitness made him "primitive" (like the Indians and the blacks) and often stood as the great unspoken reason the Boston literary establishment could not abide him. Many of their arguments against him were simply disguised ways of saying "he talks dirty." The Boston banning of Leaves of Grass in 1881—blamed on Higginson by at least one person close to Whitman82 —did not focus on poems treating homoeroticism. Throughout Higginson's writings on Whitman, however, his disapproval of the poet took this particular turn and emphasized male-male love. He consistently criticized what he called "the mere craving of sex for sex," or the "sheer animal longing of sex for sex," or "the blunt, undisguised attraction of sex to sex."83 His veiled defamations of Whitman's sexuality are all the more interesting given that Higginson himself was a man of somewhat fluid gender identifications. His famous "Letter to a Young Contributor" (the Atlantic Monthly essay to which Emily Dickinson responded) had alluded to Cecil Dreeme, a cross-dressing character in Theodore Winthrop's Cecil Dreeme (1861) whose transvestism provokes a homosexual response. Dreeme was a character based on William Hurlbut, a close friend of Higginson's youth, about whom he once remarked: "I never loved but one male friend with passion—and for him my love had no bounds—all that my natural fastidiousness and cautious reserve kept from others I poured on him; to say that I would have died for him was nothing."84 Moreover, his own Army Life in a Black Regiment (1870) exhibits an erotic fascination with black skin and bodies: "I always like to observe [black soldiers] when bathing,—such splendid muscular development, set off by that smooth coating of adipose tissue which makes them, like the South-Sea Islanders, appear even more muscular than they are. Their skins are also of finer grain than those of whites, the surgeons say, and certainly are smoother and far more free from hair."85 Higginson's attacks on the homoerotic aspects of Whitman's verse and life may have stemmed directly from potentialities and inclinations he uneasily felt in himself.

Whitman's key role in the development of modernism, in the overthrow of the Brahmin past, and in debates over the nature of what is truly "American," are all well dramatized in The Last Puritan (1936; composed 1890-1935), a novel by the one-time Harvard professor George Santayana, who never became an American citizen and who always retained the sharp edge of an outsider in his criticism of American culture. Santayana attacked the Puritan past and undercut several Brahmin writers while championing Whitman because the Puritans had been used to support a particular view of the present, because the past had been mustered to the defense of a privileged order.86 Whitman's great appeal for Santayana and for a handful of other Harvard intellectuals of the 1890s was in his promise to free people from what Santayana called "moral cramp." The main character of The Last Puritan, Oliver Alden, is told by his mother—who identifies herself with the Daughters of the American Revolution—that "nobody reads Walt Whitman except foreigners."87 She has so sheltered her son Oliver that he thought the poet "was English." With staccato insistence, Jim, his English friend, corrects this view: Whitman is the "great, the best, the only American poet . . . the only one truly American." Given that Oliver's father, Peter Alden, wants his son to "understand America" and wants to free Oliver from the distorting effects of his mother's outlook, there can be no mistaking the centrality the novel grants Whitman.88 It is only away from Boston, at sea on a ship significantly called the Black Swan, that Oliver can enjoy a harmonious blend of the sensual and the spiritual.

Nonetheless, Oliver is trapped by his ancestry, doomed by his spiritual and emotional inheritance. His story dramatically exemplifies the "mortal consequences that the dead hand of the . . . past inflicts upon its heirs."89 The Last Puritan challenges conventional accounts of the rise of New England culture most powerfully, then, by its very plot trajectory, which traces a declining arc. Santayana's novel insistently invites us to consider large movements of cultural change. "In a new nation," J. V. Matthews has observed, "an aesthetically and emotionally satisfying myth of origins is not only a necessary ingredient of an evolving national identity but a prerequisite for a sense of direction and future development."90 For various reasons, the New England myth of origins did not survive intact, as we know from the extensive displacement of once "classic" writers. In fact, New England culture was almost as well adapted to accepting (and even promoting) discontinuity as it was to insuring perpetuation of its own power. Santayana dramatizes the forces that helped, through Whitman, reconstitute American culture and in so doing clarifies the importance of freeing literature from the over-refinement of an elite class.

ALI, WHITMAN, AND "ME WE"

[O]ccasionally the beauties of democracy are presented to us undisguised. The writings of Walt Whitman are a notable example. Never, perhaps, has the charm of uniformity in multiplicity been felt so completely and so exclusively. Everywhere it greets us with a passionate preference; not flowers but leaves of grass, not music but drum taps, not composition but aggregation, not the hero but the average man, not the crisis but the vulgarest moment; and by this resolute marshalling of nullities, by this effort to show us everything as a momentary pulsation of a liquid and structureless whole, he profoundly stirs the imagination. We may wish to dislike this power, but, I think, we must inwardly admire it. For whatever practical dangers we may see in this terrible levelling, our aesthetic faculty can condemn no actual effect; its privilege is to be pleased by opposites, and to be capable of finding chaos sublime without ceasing to make nature beautiful.Aggregation rather than composition, and the pleasures of multiplicity and a liquid structureless whole: this might define the democratic voice, a voice that often expressed itself through the reiterative parallelism of nineteenth-century oratory and the ongoing traditions of the black church. Richard Wright was not necessarily invoking Whitman when he employed a lengthy lyrical parallelism near the opening of Black Boy, though he elsewhere explicitly refers to the poet. And it was more likely the rhythms of, say, Langston Hughes rather than Whitman that lay behind Muhammad Ali's incantatory answer to a reporter's question prior to his historic fight with George Foreman in Zaire for the heavyweight championship of the world. I have lineated Ali's response to highlight his use of parallelism as he explained his motives for boxing:

There is something uncanny about Ali's echoing of Whitman's sympathy for prostitutes and the downtrodden, and about Ali and Whitman's shared fondness for catalogues of place names. In the final two lines, Ali contrasts—purposefully, I suspect—free border states and slave states, the latter being paradoxical places black people could be in and from but not of, both in the nineteenth century and in recent times.I'm going to fight for the prestige, not for me, but to uplift my littlebrothers who are sleeping on concrete floors today in America,Black people who are living on welfare,Black people who can't eat,Black people who don't know no knowledge of themselves,Black people who don't have no future,I'm going to win my title and walk down the alleys,Sit on the garbage can with the wineheads,I want to walk down the street with the addicts, talk to theprostitutes,I can show them films,I can take this documentary,I can take movies and help uplift my people in Louisville, Kentucky,Indianapolis, Indiana, Cincinnati, Ohio.I can go through Tennessee, and Florida, Mississippi and show thelittle black Africans of them countries who didn't know this wastheir country.

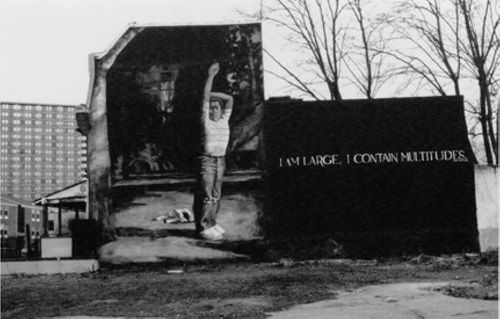

Figure 3.Nationally renowned figure painter Sidney Goodman created the mural Boy With Raised Arm. Photograph by Jack Ramsdale. Image courtesy Philadelphia Mural Arts Program.

Figure 3.Nationally renowned figure painter Sidney Goodman created the mural Boy With Raised Arm. Photograph by Jack Ramsdale. Image courtesy Philadelphia Mural Arts Program.

Following a lecture Ali gave at Harvard University, when he was asked for a poem, he paused for a moment and said "Me we," thereby composing perhaps the shortest poem in the English language.92 As George Plimpton has noted, "It stands for something more than the poem itself." In a remarkable way, Ali's two-word poem captures fundamental Whitman goals: to talk about the self to discuss all of us, to use the self to create community. In fact, if one were limited to two words in summarizing Leaves of Grass, one could not do better. Yet we should not overstate the similarity between Ali and Whitman. Ali's prose-poem in Zaire makes a more modest and particular claim than Whitman as to whom he speaks for and as. Whitman's assertion that he can comprehensively and unproblematically be the nation's body has left him open to criticism (can a white male body represent all bodies? can any body, of any hue, represent all bodies?), even as cohesion retains an ongoing appeal.93 African American commentators continue to find Whitman to be a provocative and useful resource in the ongoing search for something more complicated and satisfying than separation, a unified rather than a universalist culture.

CHAPTER 2

EDITH WHARTON AND THE PROBLEM OF WHITMANIAN COMRADESHIP

As Chapter 1 noted, "Walt Whitman" became, for many, a name signaling the outsider. Whitman himself cultivated this association by explicitly identifying his poetic voice with the American underclass, enslaved African Americans. African Americans have, in turn, responded to Whitman's poetry and its democratic reach to historically oppressed members of society. But this identification of Whitman with the underprivileged is not consistent among readers of his poetry. Some members of old blue-blood families also saw reason to identify with Whitman and his work. Rather than seeing him as a liberator of the politically oppressed, a reader such as Edith Wharton saw Whitman as a liberator of the psychically oppressed, a force who helped overthrow the burden of the genteel tradition. Her constructions of Whitman changed as her thinking and experience developed. In general, he was an enabling force in Wharton's explorations of fundamental issues concerning friendship and love, explorations that led—in both life and art—to discoveries that were often exhilarating and occasionally profoundly troubling.