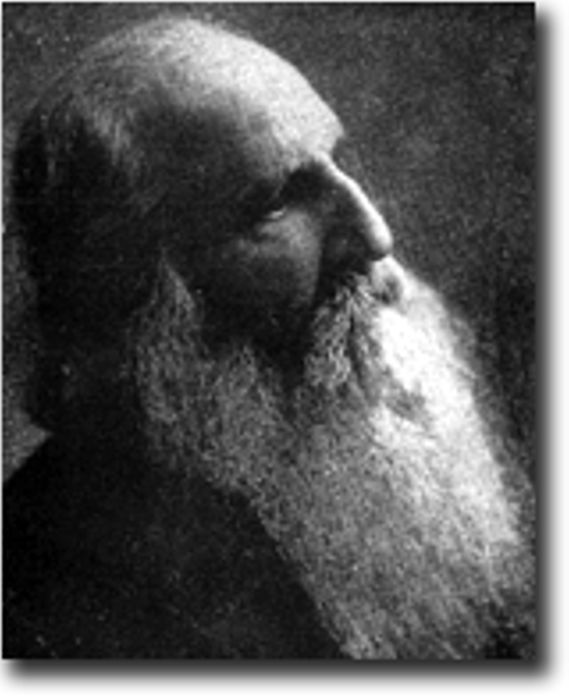

Richard Maurice Bucke

photograph of Bucke Bucke was a Canadian physician and student of the human mind who became one of Whitman's most devoted friends and supporters in the poet's later years. He was Whitman's first biographer, and his book Cosmic Consciousness (1901), which features Whitman and Bucke's messianic view of him, has won its author a minor but enduring fame.

photograph of Bucke Bucke was a Canadian physician and student of the human mind who became one of Whitman's most devoted friends and supporters in the poet's later years. He was Whitman's first biographer, and his book Cosmic Consciousness (1901), which features Whitman and Bucke's messianic view of him, has won its author a minor but enduring fame.

After several years of wandering, work and adventure—including a battle with Shoshone Indians and a trek through the Rocky Mountains in winter that cost him one of his feet and part of the other due to frostbite—Bucke received an inheritance which allowed him to attend McGill University Medical School. Further study in Europe followed. Bucke then returned to Canada, married, and for several years lived the life of a small town doctor. In 1876 he was appointed superintendent of the hospital for the insane, his profession from then on. He gained a reputation as one of the leading "alienists" of his day, and his approach to treatment of the mentally ill was progressive, deemphasizing alcohol, drugs and physical restraints in favor of useful work and a more healthful living environment.

Always a wide-ranging reader, Bucke first encountered Whitman's work in 1867. He read Whitman's poetry with intensity and fascination for several years, committing much of it to memory. (It has been alleged that eventually Bucke knew all of Leaves of Grass by heart.) One evening in 1872 Whitman's poetry led to one of the key experiences of Bucke's life. After an evening of reading poetry (Wordsworth, Keats, Shelley, and especially Whitman) aloud with friends, he experienced an overwhelming state of illumination and joy; he felt himself literally surrounded with light from an inner fire. The man of science with strong introspective and metaphysical leanings was from this time on a mystic as well.

Something similar occurred when he finally met Whitman in person. In Philadelphia on professional business, Bucke crossed the river to Camden and looked the poet up. Though their visit was outwardly unremarkable, after parting Bucke found himself in a state of "mental exaltation." This feeling continued for the next six weeks, and Bucke's devotions to Whitman continued for the rest of his life.

Many people have judged Whitman extraordinary in a variety of ways, but none has made a larger claim for him than Bucke. He believed that Whitman was not only a great writer, but a breakthrough in humanity's psychic and moral evolution comparable to Buddha or Jesus; in fact, Bucke felt that Whitman surpassed even these. Bucke dedicated Man's Moral Nature (1879), his first book on his theory of evolving consciousness, "to the man of all men past and present that I have known who has the most exalted moral nature—Walt Whitman."

Bucke's biography of Whitman (1883) was an unconventional book, as much an anthology of documents about the poet as biography. It was also a collaboration; Whitman advised throughout, revised Bucke's text, and wrote significant portions of the book himself. Always uncomfortable with Bucke's inclination to view him as a demi-god, Whitman's reworking of Bucke's text removed such claims, emphasizing instead the robustness of his personality. Bucke continued to devote much time and energy to writing, editing, and overseeing the publication of Whitman materials, including poetry, prose, correspondence, and criticism. Along with Horace Traubel and Thomas Harned, he served as Whitman's literary executor. Cosmic Consciousness was in a sense the book that Whitman would not let him write in the biography, because it does not merely present Bucke's theory of moral and spiritual evolution but also uses Whitman as central example.

Besides his literary efforts on Whitman's behalf, Bucke was also a medical consultant throughout the last years of the poet's life. Their correspondence includes a steady stream of advice from Bucke, who also treated Whitman directly when he visited. He was on hand during a crisis in 1888, and Whitman credited Bucke with having brought him through. Bucke's role was not just that of self-appointed disciple and intellectual/mystical apostle; he was also an extremely dependable, knowledgeable, and practical man, and a loyal friend.

In 1880 Whitman spent the summer with Bucke at his home in Canada. His observations of religious service at the asylum are recorded in a haunting entry in Specimen Days (1882). They traveled together down the St. Lawrence River, and the following year, in preparation for the biography, they visited places important in Whitman's earlier years in Long Island and Manhattan. The 1880 visit was the basis for an engaging but factually unreliable Canadian feature film, Beautiful Dreamers (1992), with Rip Torn as Whitman and Colm Feore as Bucke.