Friday, April 27, 1888.

Friday, April 27, 1888.

Talked an hour or more about Symonds. W. very frank, very affectionate. [See indexical note p073.2] "Symonds is a royal good fellow—he comes along without qualifications: just happens into the temple and takes his place. But he has a few doubts yet to be quieted—not doubts of me, doubts rather of himself. One of these doubts is about Calamus. What does Calamus mean? What do the poems come to in the round-up? That is worrying him a good deal—their involvement, as he suspects, is the passional relations of men with men—the thing he reads so much of in the literatures of southern Europe and sees something of in his own experience. He is always driving at me about that: is that what Calamus means?—because of me or in spite of me, is that what it means? [See indexical note p073.3] I have said no, but no does not satisfy him. But read this letter—read the whole of it: it is very shrewd, very cute, in deadliest earnest: it drives me hard—almost compels me—it is urgent, persistent: he sort of stands in the road and says: 'I won't movetill you answer my question.' You see, this is an old letter—sixteen years old—and he is still asking the question: he refers to it in one of his latest notes. He is surely a wonderful man—a rare, cleaned-up man—a white-souled, heroic character. [See indexical note p073.4] Look at the fight he has so far kept up with his body—yes, and so far won: it is marvellous to me, even. I have had my own troubles—I have seen other men with troubles, too—worse than mine and not so bad as mine—but Symonds is the noblest of us all." [See indexical note p074.1] This had been all called out by an old Symonds letter which he had been reading and which he gave to me. "You will be writing something about Calamus some day," said W., "and this letter, and what I say, may help to clear your ideas. Calamus needs to clear ideas: it may be easily, innocently distorted from its natural, its motive, body of doctrine."

Clifton Hill House, Near Bristol, Feb 7, 1872. Dear Mr. Whitman,Your letter found me today. [See indexical note p074.2] This is my permanent address. I live here in a large old house which belonged to my father—a house on a hill among trees looking down upon Bristol with its docks and churches—a picturesque labyrinth of marts and spires and houseroofs.

Your letter gave me the keenest pleasure I have felt for a long time. I had not exactly expected to hear from you. Yet I felt that if you liked my poem [See In Re Walt Whitman] you would write. So I was beginning to dread that I had struck some quite wrong chord—that perhaps I had seemed to you to have arrogantly confounded your own fine thought and pure feeling with the baser metal of my own nature. What you say has reassured me and has solaced me nearly as much as if I had seen the face and touched the hand of you—my Master! [See indexical note p074.3]

For many years I have been attempting to explain in verse some of the forms of what in a note to Democratic Vistas (as also in a blade of Calamus) you call "adhesiveness." I have traced passionate friendship through Greece, Rome, the medieval and the modern world, and have now a large body of poems written but not published. [See indexical note p074.4] In these I trust the spirit of the Past is faithfully set forth as far as my abilities allow.

It was while engaged upon this work (years ago now) that I first read Leaves of Grass. [See indexical note p075.1] The man who spoke to me from that Book impressed me in every way most profoundly—unalterably; but especially did I then learn confidently to believe that the Comradeship which I conceived as on a par with the sexual feeling for depth and strength and purity and capability of all good, was real—not a delusion of distorted passions, a dream of the Past, a scholar's fancy—but a strong and vital bond of man to man.

Yet even then how hard I found it—brought up in English feudalism, educated at an aristocratic public school (Harrow) and an over refined University (Oxford)—to winnow from my own emotion and from my conception of the ideal friend all husks of affectations and aberrations and to be a simple human being! [See indexical note p075.2] You cannot tell quite how hard this was, and how you helped me.

I have pored for continuous hours over the pages of Calamus (as I used to pore over the pages of Plato), longing to hear you speak, burning for a revelation of your more developed meaning, panting to ask—is this what you would indicate?—are then the free men of your land really so pure and loving and noble and generous and sincere? [See indexical note p075.3] Most of all did I desire to hear from your own lips—or from your pen—some story of athletic friendship from which to learn the truth. Yet I dared not to address you or dreamed that the thought of a student could abide the inevitable shafts of your searching intuition.

Shall I ever be permitted to question you and learn from you?

What the love of man for man has been in the Past I think I know. What it is here now, I know that also—alas! [See indexical note p075.4] What you say it can and shall be I dimly discern in your Poems. But this hardly satisfies me—so desirous am I of learning what you teach.

Some day, perhaps—in some form, I know not what, but in your own chosen form—you will tell me more about the Love of Friends. [See indexical note p076.1] Till then I wait. Meanwhile you have told me more than any one beside.

I have been led to write too much about myself, presuming on what you said, that you should like to know me better.

It will give me sincere pleasure to receive a copy of your book from you. I am grateful to you for purposing to give me so great a gift. Will you complete the benefit by sending me a portrait of yourself?

It is good to hear that your work does not deny you leisure. Work with an ample margin of freedom is the best thing for man; but I cannot believe in the modern Gospel of Work and no leisure. [See indexical note p076.2] This ends in a Science of Human Mechanics.

When I am free enough from home duties I hope to go to America on a tour with my wife. Then I shall request to be permitted to pay respect to you in person.

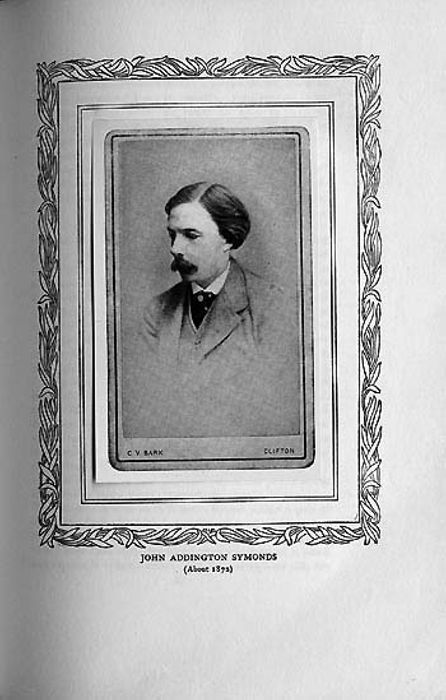

That you may know my face I enclose two portraits. The little girl in one of them is my youngest child.

I am your ever grateful and indebted John Addington Symonds.Said W.: "Well, what do you think of that? Do you think that could be answered?"

[See indexical note p076.3]

"I don't see why you call that letter driving you hard. It's quiet enough—it only asks questions, and asks the questions mildly enough."

"I suppose you are right—'drive' is not exactly the word: yet you know how I hate to be catechised. Symonds is right no doubt, to ask the questions: I am just as much right if I do not answer them: just as much right if I do answer them. [See indexical note p076.4] I often say to myself about Calamus—perhaps it means more or less than what I thought myself—means different: perhaps I don't know what it all means—perhaps never did know. My first instinct about all that Symonds writes is violently reactionary—is strong and brutal for no, no, no.

John Addington Symonds (about 1872)

Then the thought intervenes that I maybe do not know all my own meanings: I say to myself: 'You, too, go away, come back, study your own book—an alien or stranger, study your own book, see what it amounts to.' [See indexical note p077.1] Sometime or other I will have to write him definitively about Calamus—give him my word for it what I meant or mean it to mean."

John Addington Symonds (about 1872)

Then the thought intervenes that I maybe do not know all my own meanings: I say to myself: 'You, too, go away, come back, study your own book—an alien or stranger, study your own book, see what it amounts to.' [See indexical note p077.1] Sometime or other I will have to write him definitively about Calamus—give him my word for it what I meant or mean it to mean."

Symonds spoke of two portraits. The portrait of himself was still enclosed. The child portrait was missing. W. said: "It's around the house somewhere."