Tuesday, May 1, 1888.

Tuesday, May 1, 1888.

Called W.'s attention to some announcements of November Boughs already finding their way into the papers. [See indexical note p087.1] "That ought to spur me on." he said, "though as you know I am not easily spurred. I always argue that all the time there is my time: so I go slow with what I do—take the reasonable maximum of liberty." Then: "Yet you are right. We should get at that job. I'm in a pretty shaky condition, physically, right along these days—never know what may not happen overnight. I'm not afraid but I face the facts. I want the book to come out—I wouldn't like much to delay and delay and then die off with the thing hanging fire or half done. You are right—yes, you are right—we will attack the problem at once." He laughed a bit and broke out into a little recitative: "A minister was in here today—he came to give me advice—he said he had come from St. Louis, or Denver perhaps (I forget which), to give me his opinion on Leaves of Grass. [See indexical note p087.2] I told him that was hardly worth while—that I had plenty of opinions of Leaves of Grass nearer home—all sorts of pros and cons: damns and hallelujahs. But he didn't laugh or seem deterred—he went right on with his message. I must have done something to make him think I was inattentive—I didn't do it purposely—for he suddenly stopped: 'I don't believe you're hearing a word I say, Mr. Whitman,' he said. It was a good guess. I didn't mind his knowing it—so I said: I shouldn't wonder—I shouldn't wonder.' That seemed to open his eyes a little. He went very soon after that, saying to me: 'I was told you wouldn't take any advice—even good advice.' [See indexical note p087.3] I said again: 'I shouldn't wonder—I shouldn't wonder,' and while he was trying to intimate his disgust I added: 'You know I get so much good advice, and so much bad advice, so much nearer home.' The thing seems incredible: I don't believe anybody but a minister of the gospel would do such a thing—would have been guilty of so egregious an impertinence. When he was all gone I had a long laugh all to myself." [See indexical note p088.1] Then W. burst into laughter again, exclaiming: "That's a tale worth putting down in the book." I assented, but said: "So it is. But I've got a match for it." "I don't believe it—but let's hear." "My grandmother was sitting on the front step one day—she was well on to eighty, you know—quietly looking about at things. A clerical came along and saw her, stopped and sat down on the step at her side. 'Madam,' he said, 'you are very old: are you prepared to die?' She was of course annoyed and said to him tartly: 'Sir! if you were half as well prepared to die as I am you would be a happy man!'" W. was very much amused. [See indexical note p088.2] "Yes, that's a good match: that's worth being put down in the same book!" And after a little interval in which nothing was said by either he remarked: "The ministry is spoiled with arrogance: it takes all sorts of vagaries, impudences, invasions, for granted: it even seizes the key to the bedroom and the closet."

W. talked again about literary honesty. [See indexical note p088.3]

"It's not quite the thing to take language by the throat and make it yield you beautiful results. I don't want beautiful results—I want results: honest results: expression: expression. You know we talked about this the other day: you may have thought I was over vehement, thought, as for that, I don't see how a fellow can say too much on that score. Since we talked I have come across a letter from John Burroughs that finely illustrates my point. [See indexical note p088.4] It is an old letter, written by John from England in 1871: a letter in which he lets himself go—talks out—isn't trying to be judicial or qualified—which is on the square all through. See what I wrote on it then at the time in red ink." I took the letter from his hand and read the memorandum: "splendid offhand letter from John Burroughs—? publish it." W. resumed: "John

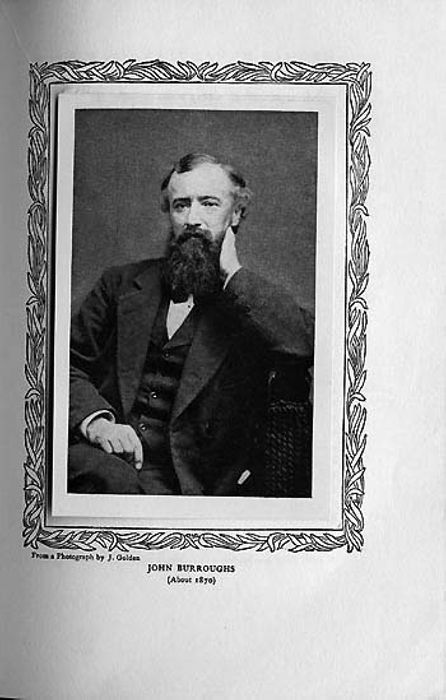

John Burroughs (About 1870)

has a few of the simply literary habits—not many—not enough to spoil or even much hurt the batter. You will notice the postscript, written the next day. [See indexical note p089.1] He asks himself then whether he hadn't gone too far the day before—shows that after all he was a little bit afraid of his enthusiasm. He had slept over night—the judicial atmosphere was returning. But the letter itself? There is no discount on the letter—it is a superb example of let go: let hell come if it must, but let go. Does this seem lawless? [See indexical note p089.2] Of course I mean let go within the law—within your own law, not somebody else's law: every individual within his own law."

John Burroughs (About 1870)

has a few of the simply literary habits—not many—not enough to spoil or even much hurt the batter. You will notice the postscript, written the next day. [See indexical note p089.1] He asks himself then whether he hadn't gone too far the day before—shows that after all he was a little bit afraid of his enthusiasm. He had slept over night—the judicial atmosphere was returning. But the letter itself? There is no discount on the letter—it is a superb example of let go: let hell come if it must, but let go. Does this seem lawless? [See indexical note p089.2] Of course I mean let go within the law—within your own law, not somebody else's law: every individual within his own law."

I am writing to you on the spur of the moment in hopes it will bring me to my senses, for I am quite stunned at the first glance of London. [See indexical note p089.3] I have just come from St. Paul's and feel very strange. I don't know what is the matter with me but I seem in a dream. St. Paul was too much for me and my brain actually reels. I have never seen architecture before. It made me drunk. I have seen a building with a living soul. I can't tell you about it now. I saw for the first time what power and imagination could be put in form and design—I felt for a moment what great genius was in this field. [See indexical note p089.4] But I had to retreat after sitting down a half hour and trying to absorb it. I feel as if I should go nowhere else while in London. I must master it or it will kill me. I actually grew faint. I was not prepared for it and I thought my companions the Treasury clerks would drive me mad they rushed round so. I had to leave them and sit down. Hereafter I must go alone everywhere. My brain is too sensitive. I am not strong enough to confront these things all at once. [See indexical note p089.5] I would give anything if you was here. I see now that you belong here—these things are akin to your spirit. You would see your own in St. Paul's, but it took my breath away. It was more than I could bear and I will have to gird up my loins and try it many times. Outside it has the beauty and grandeur of rocks and crags and ledges. [See indexical note p090.1] It is nature and art fused into one. Of course time has done much for it, it is so stained and weatherworn. It is like a Rembrandt picture so strong and deep is the light and shade. It is more to see the old world than I had dreamed, much more. I thought art was of little account, but now I get a glimpse of the real article I am overwhelmed. I had designed to go on the continent, but I shall not stir out of London until I have vanquished some part of it at least. If I lose my wits here why go further? But I shall make a brave fight. I only wish I had help. These fellows are like monkeys. I have seen no one yet but shall try to see Conway tomorrow. [See indexical note p090.2] I write this dear Walt to help recover myself. I know it contains nothing you might expect to hear from me in London, but I have got into Niagara without knowing it and you must bear with me. I will give facts and details next time. Go and see Ursula.

With much love, John Burroughs.[See indexical note p090.3] Oct. 4—I went today to see Conway but he was not in—so I went back to St. Paul's to see if I really make a fool of myself yesterday. I did not feel as before and perhaps never shall again. Yet it is truly grand and there is no mistake. It is like the grandest organ music put into form.

P. S. I hope you and O'Connor will make an effort to come over here. You need not mention it but I know it is not settled at all who will come. This you can rely upon, but there will be no more bonds sent until in November.

"Now I see what you mean by your reference to the foot-note." [See indexical note p090.4] "Yes," replied W., "the letter is perfect—it deserves to go alone. The footnote is an impertinence. The foot- note, however, helps to clear up the sort of literary questions we have been turning over together."