Thursday, May 24, 1888.

Thursday, May 24, 1888.

[See indexical note p200.3] W. received today a copy of The Gnostic, published by George Chainey in San Francisco, which, said he, "I could not attempt to read." Also a little volume of sonnets from Warren Holden, of whom he says he "knows nothing." [See indexical note p200.4] "I met Chainey in Boston—saw him, received him, here in Camden on several occasions: am entirely familiar with his career. I could not easily forget how he stood up for the Leaves in Boston on the Tobey days." W. has been out driving but once this week. [See indexical note p200.5] "I am getting more and more satisfied with my bed and chair, which is suspicious." Is at last full of his book, after "hesitations plenty," in his own words, "and delays to spare." Says he wants it out in two or three months—three at the most: is almost eager. Explains: "The fall in my pulse is getting more and more evident: I've got no time to lose." The Presbyterians are celebrating a centenary in Philadelphia. [See indexical note p200.6] W. says: "Let them keep at it; it's like a cloudy day—it'll pass off by and bye." Woodrow is being tried before the Presbytery at Baltimore for his endorsement of the theory of evolution. "The question seems to be—did Adam come from the dust of the earth or from a baboon—isn't it? And now the Presbytery is to give high and mighty judgment in the matter. Good for the Presbytery! [See indexical note p201.1] Let them go on: the globe will still go round whatever the way the Presbytery decides it. The universe may even survive the withdrawal of the endorsement of the Presbytery." In talking about signatures W. said: "O'Connor once took one of my signatures to a clerk in the Treasury who so cleverly duplicated it that I could not myself tell the two apart."

[See indexical note p201.2] W. gave me a piece of cardboard which contained a penciled profile over which he had written: "Pencilling by Edward Clifford English artist what struck him as an American type of physiognomy, head &c. Oct: 1884." I asked: "Did the drawing impress you?" "It was very interesting—not necessarily convincing. Clifford has been about some—struck me as being a close observer. It was a point of view not quite to be assumed just yet: I feel myself that the American is being made but is not made: much of him is yet in the state of dough: the loaf is not yet given shape. [See indexical note p201.3] He will come—our American. Such a drawing as this will have more value later on when the type of face that struck Clifford in individuals here and there may be more generally evolved. I don't think I have any views on the subject myself: I see our new man rather more in moral, spiritual, lines, than in physiognomy." I said: "I would give a good deal to own this card." "Don't give anything to own it: own it anyway: take it along: I shall never want it again."

[See indexical note p201.4] W. again: "I've got some news for you: I am going to accept Harned's invitation to a jamboree at his house next Thursday in honor of my own seventieth birthday: you must be sure to be there: and Aggie, too: tell her. I have about made up my mind to live another year: why not? Considering all the things I have to do I will need at least a year." Was there anyone he wished particularly to ask for the "jamboree"? "No—I am sure not—at least not anyone necessarily, though perhaps Tom Donaldson—perhaps Talcott Williams—though I don't know: I am so liable not to get there at the last minute that it seems like asking people from a distance to take too many chances." [See indexical note p202.1] "You like Williams." "Yes, I do. Someone was here the other day—spoke of him as a prig. He is not that—he is a man, like Gilder, who possesses more regard for the conventionalities than we do, but he is square with it all: take even Emerson—he was somewhat of the same strain. [See indexical note p202.2] But there is more to Williams than all that: he has original talent of no common order—but I guess it will never get out: a man tied up as Talcott is with a great newspaper in a big city has little chance to make the best of himself." How about Donaldson? "He, too, is all right—though not quite so much all right as Talcott. [See indexical note p202.3] I feel that Tom Donaldson is my friend: he suffers from some severe shortages: but after that is said what is left is good stuff. [See indexical note p202.4] Tom has got too close to politics—that is his worst fault: some things that have touched him have stuck: yet he is so genial, so red—so real—I don't want to put any ifs in my love for him." It would be fine to have O'Connor come up from Washington? W.'s eyes twinkled: "That would be the crowning triumph—but it is impossible. He writes me that he is worse disabled than I am."

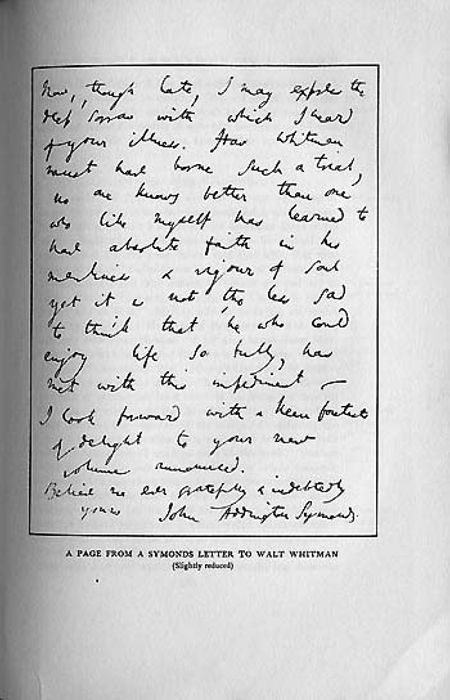

[See indexical note p202.5] W. gave me a Symonds letter again, saying of it: "The New Republic he speaks of there was Harry Bonsall's paper here in Camden. It is a beautiful letter—beautiful: Symonds could crowd all the literary fellows off the stage for delicacy—directness—of pure literary expression: yes, honest expression. [See indexical note p202.6] Symonds is cultivated enough to break—bred to the last atom—overbred: yet he has remained human, a man, in spite of all. You will see that he harps on the Calamus poems again—always harping on 'my daughter.' I don't see why it should but his recurrence to that subject irritates me a little. This letter was written thirteen years ago—thirteen years (that was the most depressed year or two of my life—1875—6): Symonds is still asking the same question. I suppose you might say—why don't you shut him up by answering him? [See indexical note p203.1] There is no logical answer to that, I suppose: but I may ask in my turn: 'What right has he to ask questions anyway?'" W. laughed a bit. "Anyway, the question comes back at me almost every time he writes. He is courteous enough about it—that is the reason I do not resent him. I suppose the whole thing will end in an answer, some day. It always makes me a little testy to be catechized about the Leaves—I prefer to have the book answer for itself." I took the Symonds letter and read it."

Gais, Switzerland, June 13, 1875. My dear Sir.[See indexical note p203.2] I was very much delighted some weeks ago to receive a copy of the New Republic with a little memorandum in your handwriting. Time does not diminish my reverential admiration for your work, nor do the unintelligent remarks of the English press deter me from giving expression to the same in print. [See indexical note p203.3] I hope soon to have an opportunity to explain at large, in a new series of critical studies of the Greek Poets, what I meant in the little note alluded to by the reviewer of the Quarterly, and to show how it is only by adopting an attitude of mind similar to yours that we can in this age be in true unity with whatever great and natural and human has been handed to us from the past. I was the more pleased to have this communication from you, because I feared that the last time I wrote to you I might perhaps have spoken something amiss. I then—it was about three years ago, I think—sent you a poem called Callicrates and asked you questions about Calamus. [See indexical note p203.4] Pray believe me that I only refer to this circumstance now in order to explain the reason why since that time I have kept silence from a fear I might have been importunate or ill-advised in what I wrote. There was really no reason why you should have noticed that communication; and it gives me great satisfaction to feel that your friendly remembrance of me is not diminished.

Now, though late, I may express the deep sorrow with which I heard of your illness. [See indexical note p204.1] How Whitman must have borne such a trial, no one knows better than one who like myself has learned to have absolute faith in his manliness and rigor of soul. Yet it is not the less sad to think that he who could enjoy life so fully, has met with this impediment.

I look forward with a keen foretaste of delight to your new volume announced.

My permanent address is: Clifton Hill House, Clifton, Bristol. I should have written earlier had I not been moving rapidly from place to place during an Italian journey.

Believe me ever gratefully and indebtedly yours John Addington Symonds.I said to W.: "That's a humble letter enough: I don't see anything in that to get excited about. [See indexical note p204.2] He don't ask you to answer the old question. In fact, he rather apologizes for having asked it." W. fired up. "Who is excited? As to that question, he does ask it again and again: asks it, asks it, asks it." I laughed at his vehemence: "Well, suppose he does. It does no harm. Besides, you've got nothing to hide. [See indexical note p204.3] I think your silence might lead him to suppose there was a nigger in your wood pile."

"Oh nonsense! But for thirty years my enemies and friends have been asking me questions about the Leaves: I'm tired of not answering questions." It was very funny to see his face when he gave a humorous twist to the fling in his last phrase. [See indexical note p204.4] Then he relaxed and added: "Anyway, I love Symonds. Who could fail to love a man who could write such a letter? I suppose he will yet have to be answered, damn 'im!" I remarked: "Symonds here addresses you as 'sir.' You were not yet 'master' at that time."

"No—not master.

A Page from a Symonds Letter to Walt Whitman

I don't know which I like least—sir or master: they both leave a bad taste in the mouth."

[See indexical note p205.1] When I left W. cried after me: "Whatever you do forget don't forget the thirty-first: and push along November Boughs the best you can: I lean on you for this job, so you must stiffen up enough for two!"

A Page from a Symonds Letter to Walt Whitman

I don't know which I like least—sir or master: they both leave a bad taste in the mouth."

[See indexical note p205.1] When I left W. cried after me: "Whatever you do forget don't forget the thirty-first: and push along November Boughs the best you can: I lean on you for this job, so you must stiffen up enough for two!"