Tuesday, August 14, 1888.

Tuesday, August 14, 1888.

To W.'s at one o'clock. Sat in chair. Bright and chatty—"garrulous," he said of himself. He had been rooting in an old basket of odds and ends, "destroying a lot of stuff, saving some"—looking at me with reassuring eyes: "I haven't destroyed anything it was better to keep." Gave me galley prints of Burroughs'

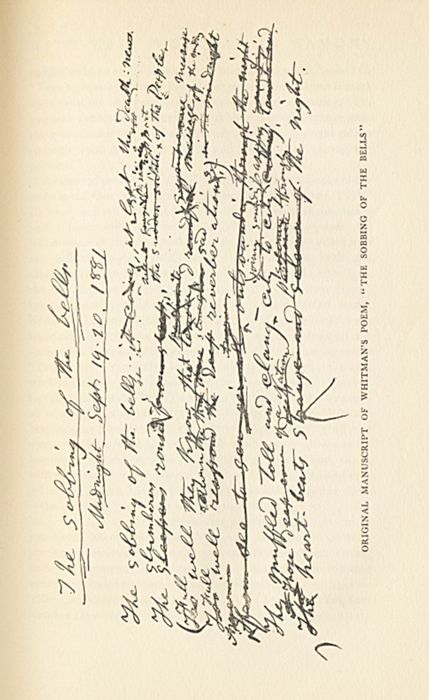

ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPT OF WHITMAN'S POEM, "THE SOBBING OF THE BELLS"

Science and Theology. "I have never read it," said W., "I can't get up an interest in such subjects: Ingersoll and Huxley seem to be my only exceptions for anti-theological reading. Do you take John along with you—read him: if you can make anything particular out of him there tell me of it. I would rather go with John among the birds and beasts than among the parsons."

ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPT OF WHITMAN'S POEM, "THE SOBBING OF THE BELLS"

Science and Theology. "I have never read it," said W., "I can't get up an interest in such subjects: Ingersoll and Huxley seem to be my only exceptions for anti-theological reading. Do you take John along with you—read him: if you can make anything particular out of him there tell me of it. I would rather go with John among the birds and beasts than among the parsons."

He showed me several of his little improvised note-books of the war-time. One was marked "September & October, 1863." He read some memoranda from it to me. "I carried sometimes half a dozen such books in my pocket at one time—never was without one of them: I took notes as I went along—often as I sat—talking, maybe, as with you here now—I writing while the other fellow told his story. I would take the best paper (you can see, the best I could find) and make it up into these books tying them with string or tape or getting someone (often it was Nellie O'Connor) to stitch them for me. My little books were beginnings—they were the ground into which I dropped the seed. See, here is a little poem itself"—he handed me the book: "Probably it is included in the Leaves somewhere. I would work in this way when I was out in the crowds, then put the stuff together at home. Drum Taps was all written in that manner—all of it—all put together by fits and starts, on the field, in the hospitals, as I worked with the soldier boys. Some days I was more emotional than others, then I would suffer all the extra horrors of my experience—I would try to write, blind, blind, with my own tears. O Horace! Horace! Horace! Should I ever get to Washington again I must look up my old cherry tree there—the great old tree under which I used to sit and write, write long, write. I want to give you one, several, of these books, if you would like to have them from me. They are more than precious—precious because they recall the old years—bring back the pictures of agony and death—reassociate me with the scenes and human actors of that tragic period.

He spelled out a name from the book—Lige Fox: "Yes, I remember Lige—he was from Northwest—very free-going, very honest-like. Some day I'll gather all the stories of these books together and give them out: what a jail delivery there will be! There's the story of Lige: it plays the dickens with the character of Stonewall Jackson—taking him down (whipping him off) the pedestal he has decorated by general consent. Everybody in Washington wanted to think well of Jackson—I with the rest—and we were inclined to the very last to distrust the many stories which seemed to reflect upon his glory. But Lige's tale was so modestly told I could not doubt it—was told so entirely without brag, bad temper—without any desire for revenge—in fact, without any consciousness that Jackson had done anything but what was usual and right. Lige had been captured. Jackson subjected him to an inquisition—wanted information—would have it—would, would, would, whether or no. Lige only said and kept on saying: 'I'm a Union soldier and can't do it.' Finding he could get nothing from Lige Jackson punished him by making him walk the ten miles to Richmond while the others were conveyed. I could never think the same of Jackson after hearing that—after seeing how he resented in Lige what was a credit to him—what Lige could not have given and what Jackson could not have taken and either remain honest. And think of it, too! Jackson such a praying man—going off into the woods, flopping on his knees everywhere and anywhere to pray! There are a number of reputations I could prick in that same fashion. It always struck me in the War, how honest and direct the private soldiers were—how superior they were, in the main, to their officers. They would freely unbosom to me—tell me of their experiences—perhaps go into minutest details—always, however, as if everything was a matter of fact, was of no value—as if nothing was of enough significance to be bragged of. Their stories justified themselves—did not need to be argued about. My intuitions rarely made a mistake: I believed or did not believe in certain men because—and that was all the reason I had for it. I could always distinguish between a veteran and a tyro: the don't-cry, the calmness, the entire absence of priggishness in the veteran was obvious, conclusive, at once."

W. contrasted the punctiliousness of Lee and the freedom of Grant. "Grant was the typical Western man: the plainest, the most efficient: was the least imposed upon by appearances, was most impressive in the severe simplicity of his flannel shirt and his utter disregard for formal military etiquette. Lee had great qualities his own but these were the greatest. I could appreciate such contrasts: I lived in the time, on the spot: I lived in the midst of the life and death vigils of those fearful years—in the camps, in the hospitals, in the fiercest ferment of events."

We talked some about a Miller letter—an old letter. W. said of it: "It takes me back and sets me forward. Joaquin himself lit a pretty good torch at the divine fire. The singers come sometimes in streams—spiritual streams: are swept into the world, out of the world again, fortified by anonymous inspirations, not great or little in themselves, seeming to be in the round-up only a voice to utter the dreams, hopes faiths, of the people. If you look at it that way the best man is not enough best to be vain of his performances." Asked me: "Can you read Miller's letter? I always have trouble with his handwriting."

N. Y. Apr. 16, '76. My dear Walt Whitman:I met a mutual friend last evening who informed me he had just procured your books from you by mail, and I directed him, since he had been so fortunate and knew how to do it, to write at once for me and have the books sent to the Windsor Hotel.

Well I am not living at the Windsor, and in fact have no fixed abode. Besides, I want your name written in the books if not asking too much for so little. And so on reflection I have decided to write you that when you receive my order through Mr. Johnston, you will please write in the books, saying they are from you to me, and then lay them to one side and I will call and get them next month. For when the Centennial opens I want to bring you some friends who are so anxious to meet the good and the great gray Poet. Thine.

Of course it is idle for me to congratulate you on your accession to immortality and your well deserved renown. I will only say that my soul and my sympathy all go out towards you and I often think of you as the one lone tree that tops us all, battered by storm and blown but still holding your place, serene and satisfied.

Hoping to see you early in May—Good bye and the gods be with you.

Joaquin Miller.W. laughed as he said: "Some newspaper man in New York who wrote as though he saw Miller with me somewhere said: 'Their poetry may be no good but there's no discount on their curls.' And he said something more. He said: 'If hair is poetry then Walt Whitman ought to be a great success.' So you see everybody is not deceived by our disguise. I can't make out all the arguments on the other side: some of them are not clear: but this man was a good shot. Don't you think he was good shot enough to bring down his game? Or maybe he was a barber in masquerade." So W. talked amusedly. I had a letter from Stedman today. Read some of it to W. who said: "I disapprove of the calendar anyway—will therefore not grieve if it fails to go through. Stedman is generous to take an interest in it. I am proud, you know, Horace, when I think of Stedman as my friend—but you know the wife, mother, of that household is no less my friend: that sets me up extra high. I have been more than lucky in the women I have met: a woman is always heaven or hell to a man—mostly heaven: she don't spend much of her time on the border-lines." W. asked me to write to Burroughs. "Tell him that for the past week I have really been getting a certain sort of grip on things again. Tell him it looked like total ruin but that our stock threatens to retrieve itself." Signed for me two portraits I received from Mrs. Talcott Williams. Also give me a five pound note to have cashed for him. "I got rooting into old things today by accident. I asked Mary for something that was down stairs and she brought up an entire basket, which I am now sorting out. You are liable to get a number of rag-babies before I get through with my scavengering." This is the Stedman letter:

44 East 26th st., New York, Aug. 12, '88. Dear Mr. Traubel,My thanks for your very good note. But surely I still possess the means and the privilege of joining, for the present, in a matter which you make so light for each member of the Circle. I only meant to intimate that I am unable to apply any noteworthy sum, in view of my obligations. . . . . . . . . . Nor can I pledge any contributions for an indefinite period. But I can easily spare three dollars a month, and must beg you to receive now the enclosed six dollars for August and September, and also to let me know if any special sum is needed at any time.

Don't speak to Walt of the following. The calendar reached me August 1st, long after all Christmas books &c. had been arranged for by the book-trade. The Scribners say that they think it admirable, and more likely to "take" than any other calendar that could be devised; but that the calendar idea has been worked to death, overdone, and they have resolved not to issue one henceforth. The Cassell's are now considering the matter, but I fear it is quite too late for this year.

You may tell Walt that I have selected thirteen pages of his poetry, with great care, for our Library of American Literature, and am going to have him well represented. I hope Linton will let us use his engraving. If not we will make a new engraving of W. W. for vol. VIII.

Sincerely yours, E. C. Stedman.I did not read W. the first part of Stedman's letter. He does not know how I am paying for the nurse. The "circle" is my own creation. I read him the calendar matter, in spite of Stedman's interdiction, because I knew he was not stuck on the idea of piecemeal selections made from his book—would rather

have the scheme fail than succeed. W. said of the letter: "The cut belongs to me still—it is not Linton's: say yes to Stedman—yes, yes. Have you read all the note, Horace. All I should hear? Eh? Just so—just so. Give him my love. I haven't things ready-made to say to him. Just give him my love. Let him know too—or I will let him know—that his hospitality to me, to the Leaves, in his big book is taken by me for what it is intended to signify." W. every now and then will reel out this couplet:

"Not heaven itself upon the past has power,

But what has been has been—and I have had my hour."

Today I found it written in his hand on an old slip of paper with this superscription: "Horace, translated (improved) by Dryden."