Thursday, September 6th, 1888.

Thursday, September 6th, 1888.

7.45 p. m. W. had been reading Old Mortality. "Scott again?" "O yes, only to kill time." Laid aside his book and talked. Was he well? "Yes—pretty well—but not quite so cocky as Sunday and Monday." Gilchrist was over. Spoke of Gilchrist's life of his mother: "You should read it—read my copy: Karl Knortz has it now, but we can get it back. You will not find the book to equal your great expectations, if you have any—will perhaps be disappointed. It is true much of the book is made up of things written by Mrs. Gilchrist—but writing was not the best of her. The best of her was her talk—to hear her perfectly say these things which she has only imperfectly written. I shall never forget—never forget: she is over there now, where you are—eyeing me, overflowing with utterance. She was marvellous above other women in traits in which women are marvelous as a rule—immediate perception, emotion, deep inevitable insight. She had such superb judgment—it welled up from a reservoir of riches, spontaneously, unpremeditatedly. Women are ahead of us in that anyhow—way ahead of us. It was because she was that kind of a woman that I always trusted Mrs. Gilchrist's picture of Carlyle—of the Carlyles. She was not a blind dreamer—a chaser of fancies: she was concrete—spiritually concrete, I might say: not in the sordid sense of it but the big, the high. She was practical enough to know just how to ask that dangerous question, will it pay? and to answer it with high meanings. I know nothing more miserable, sickening, than Will it pay? as it is usually asked. This is not a tonight's opinion: it is premeditated—what I have come to by careful thought: I want you to regard it as much. For me it is conclusive."

I brought W. Froude's Carlyle in London and a copy of this week's Unity containing a poem by Sidney Morse. Along with other things I had pages 16 to 32 November Boughs—first printed sheet. W. was as eager as a child as he examined it. "Good!" "Fine!" "Done at last!" "Hurrah!" "Hunkie-dory!" Many exclamations. I asked: "Where are your doubts now?" "Gone, gone, gone utterly." He was silent. Then: "I count on nothing physical till I see it—not even a promise of marriage till the marriage." And yet he confessed: "This defied augury, it came out so fine: it's the best presswork I have ever had on any one of my books. Think of the agonies that have led up to it, Horace!" Afterwards he added: "Tell them that when they are all done with the work I'll come over, or send someone over to represent me, and we'll all take a drink together." Felicitated himself upon the arrangement of one of his pages. "My printer's eyes are never deceived." Turning over a few pages. "Yonnondio: you notice that name? They printed it in The Critic first, and the Critic fellows objected to it that my use of the word was not correct, not justified. You remember, see"—pointing—"I make it mean lament and so forth: they say, no, that is not it: Yonnondio signifies governor—was an Indian name given to the French governors sent over to this continent in colonial times. No doubt there's considerable to warrant their argument, but"—putting his forefinger down on the poem and looking at me waggishly—"I had already committed myself to my own meaning—written the poem: so here is stands, for right or wrong." I asked him where he got hold of his own construction of the word. He replied: "From an old man—a wise, reticent old man—much learned in Injun tongues, lore—in Injun habits and the history of them so far as known. You never have asked Brinton? I wish you would—for me: he would know—something, at least. The debate is like many others—inconclusive. I never knew a controversy of this character—each side ready to swear to its accuracy, full of the arrogance of learning, equipped with book knowledge—to end in anything like a settlement: the problem was always as wide open at the end as at the start."

Afterwards pointing to the Grant poem he closed the sheet and said: "It was in Harper's Weekly: a young fellow there, who was friendly to me, sent for it. Grant was dying at the time—or thought to be. After I had sent off the poem Grant revived, so, while it was held, I wrote and dispatched the afterpiece, which was finally printed along with the original lines. Now"—indicating the poem—"it is back to its first shape again: Grant is dead. It was the last thing the Harpers took from me. This [With Husky Haughty Lips O Sea!] was the last piece proper in the Magazine: the Grant piece went in solely through the friendship of that young man. I have the feeling that the Harpers wish no more of me." W. adds Old Age's Lambent Peaks to go in on the last page preceding After the Supper and Talk. Was he going to include the Sheridan piece? "No—I am not particular about that. The old age poem belongs in the book—is in a sense almost necessary: might be last of all, indeed, following After the Supper and Talk—but somewhere, close to the end: it must go in." I told W. Harrison Morris in telephoning today asked: "What does the poem mean?" "You didn't tell him, did you? I never tell. It's my secret until the next fellow catches on by himself—then it's his secret, too. What does it mean? How should I know? Tell him to tell me?"

W. picked up the Pall Mall pamphlet containing a reproduction of Gilchrist's Whitman. "You have seen it? It's pretty doubtful to me—pretty doubtful: Herbert has gone way off to make me rather than staying close by: I am only to be done right close by. Mrs. Coates spoke when she was here of some superb picture. She certainly did not mean this—she could not have called this superb." "Why not? After Bonsall's verdict on Frank Fowler's portrait we might expect anything." W. laughed. "But that was a good piece of work, Horace—well done—splendidly done." "Yes, but it was not you." He nodded. "That's right, too: it was a bad go as a portrait, wasn't it?" W. said he was "still wondering" what had "brought Herbert over to America." "Herbert must have had a windfall somehow—sold a picture, maybe: maybe borrowed a thousand pounds or so from his brother. Did I ever tell you about Percy Gilchrist? He's another son—invented some steel process—has made a million dollars or more by it, God help 'im! A million dollars is a lot of baggage to get in a man's way, ain't it? A million dollars would spoil me for life. Herbert and Talcott Williams seem to entertain quite a shine for each other. I remember Herbert once said to me: 'I can easily see how a man in England might want to come here but I don't see how a man once on this side would want to go back.' Herbert is a fellow you should know, Horace, though I am not sure you would quite gee together. Herbert is English to the jumping off place: he is aggressively national. Talcott is not an American by birth—Syrian, I think: born, however, of English or American parents."

Intended to write Morse today but had not done so. A letter came from Bucke while I was there. I gave the printers at Ferguson's today a box of cigars as from Walt, who was greatly pleased. "It was right, it was good, and, as the old lady would say, I am glad you had the wit to do it." W. gave me a Swinton letter with the suggestion that I should "notice the jubilant tone of John's mood," adding: "Swinton sometimes seems to get in the dumps awful—is down in the mouth about the tardiness of the people to respond to the appeal of the economic radicals. The people will come along in their own time—yes, and take their time, too." This is what Swinton wrote:

John Swinton's Paper, New York, Feb. 13, 1885. My dear Walt—The last honor that decorates the brow of genius is now yours, and it is that I herewith introduce you to a live New Zealander—a professor from New Zealand—Prof. Brown of Canterbury College, New Zealand. He's an old admirer of the bard of Paumanok (fish-shaped) and is anxious to meet you; and so I give him this note to you. I know you will be glad to meet him. I shake your hand.

John Swinton."That's the way John makes fun and is dead in earnest at the same time," said W.: "New Zealand is pretty far around: some day we will girdle the globe." W. mentioned Weir Mitchell: "He is my friend—has proved it in divers ways: is not quite as easy-going as our crowd—has a social position to maintain: yet I don't know but he's about as near right in most things as most people. I can't say that he's a world-author—he don't hit me for that size—but he's a world-doctor for sure—leastwise everybody says so and I join in." W. sent Musgrove out for some envelopes. When they were brought W. said: "No—they won't do—they don't satisfy me for shape: I like a shapely envelope. What are you laughing about, Horace? Oh, you think I'm fussy? No—I'm only esthetic!" He laughed. "Someways I do, someways I don't care, for things: they hit my eye or they don't: I can't always say why I like or don't like but I am quite firm in my preferences." He has not yet completely arranged the Hicks for the Herald.

I had a long note from Morse today. The minute W. heard me say so he was impatient to have it read. He stopped me again and again with comments. When Morse spoke of being "immersed" in his novel, Jefferson Brown, W. said: "Stop right where you are and tell me about it. Morse never read it or any part of it to me: is it like Mrs. Ward's book?" Morse mentioned "the more Bohemian" of his friends and said: "I feel certain of them." W. asked: "Does he mean us?" He was much interested in Morse's purpose to make a big Emerson bust for Edward Emerson. "His Emerson can't be beat—it's a final triumph."

"I rather prefer the big head of Emerson left here by Morse," says W.:"it has great merit." No copies were ever taken. It is here still. Vila Blake said to Morse: "The small head is human, the large divine."

"That is striking" said W.: "Tell me about Blake—who he is." W. then talked in a general way about Morse: "I had the idea of getting a piece of ground and having him put up a rig here—a den in which he could have his own way: plenty of floor room—tall ceilings, sky-lights, air: getting everything in character with Sidney's big, generous ideas of work. I was ready to put two or three hundred dollars into it for him. Every literary fellow, artist—every man who has a big job of work to do—should have his own den—a coop entirely his own—with a cot in it, if need be, and a stove: a studio with a human side to it." Morse once had such a studio at Quincy. I spoke of it. W. said: "That all sounds good: that's the same idea. Morse has grown wonderfully the last two years—thrown off a coat or two—developed, evoluted (that's the word: evoluted!)

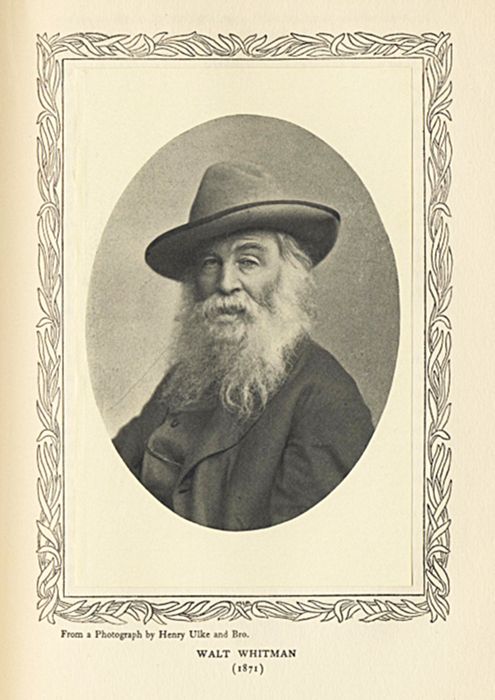

From a Photograph by Henry Ulke and Bro.

From a Photograph by Henry Ulke and Bro.

WALT WHITMAN

(1871)

—will go on to the end getting a little higher up all the time. I don't know but Chicago is just the place for him: if he can get a top-floor room somewhere and a landlord who won't worry him too much about the rent. Will you write Morse? Yes? Well—give him my love—tell him I have all sorts of faith in his success. Tell him that we miss him here—that his presence was a benediction: that we have never had any doubt about our love for him."

W. gave me a copy of a Washington (1871) portrait made by Ulke. I said of it "It has a William Morris lay-out." He replied: "Do you say so? It would please O'Connor to hear you say that. Some of them say my face there has a rogue in it. O'Connor called it my sea-captain face. Some newspaper got a hold of a copy of the photograph and said it bore out the notion that Walt Whitman was a sensualist. I offered one to a woman in Washington. She said she'd rather have a picture that had more love in it. It's a little rough and tumble, possibly but it's not a face I could hate. Could you? Honest Injun, Horace: could you hate it?"