With Walt Whitman in Camden (vol. 9)

October 1, 1891 - April 3, 1892

9 [Begin page ii]

Edited by Jeanne Chapman

Robert MacIsaac

Foreword by

Ed Folsom W L BENTLEY OREGON HOUSE - CALIFORNIA [Begin page iv]

[Electronic edition published with the kind permission of the Fellowship of Friends and W.L. Bentley Publishing.]

Copyright 1996 by the Fellowship of Friends, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by

W L Bentley - PO Box 887 - Oregon House, CA 95962

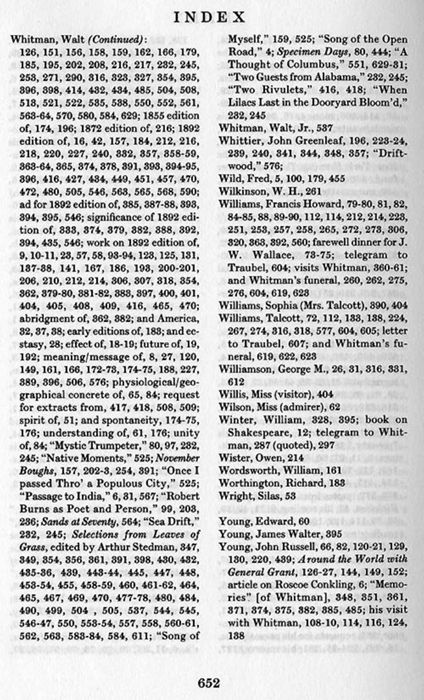

To HORACE TRAUBEL

(1858 - 1919)

CONTENTS

| ILLUSTRATIONS CONTAINED IN THIS VOLUME | viii |

| LETTERS CONTAINED IN THIS VOLUME | ix |

| EDITORS' PREFACE | xi |

| FOREWORD | |

| Horace Traubel (1858-1919) | xiii |

| CONVERSATIONS | |

| October 1-31 1891 | 1 |

| November 1-30, 1891 | 102 |

| December 1-31, 1891 | 192 |

| January 1-31, 1892 | 289 |

| February 1-29, 1892 | 409 |

| March 1-31, 1892 | 496 |

| April 1-3, 1892 | 627 |

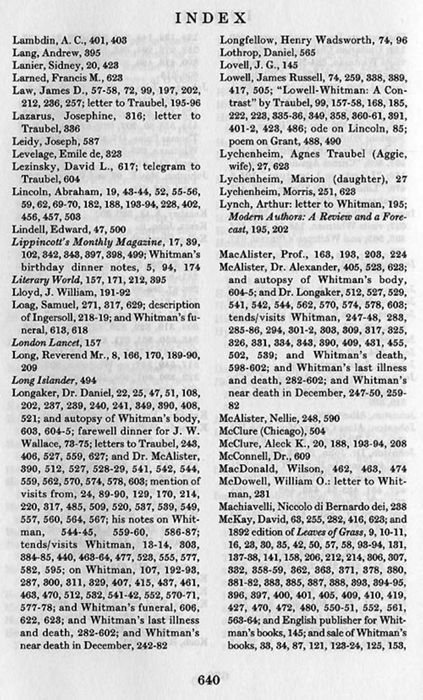

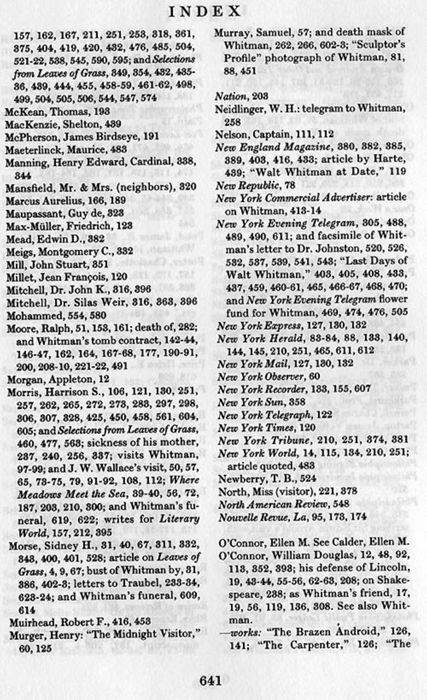

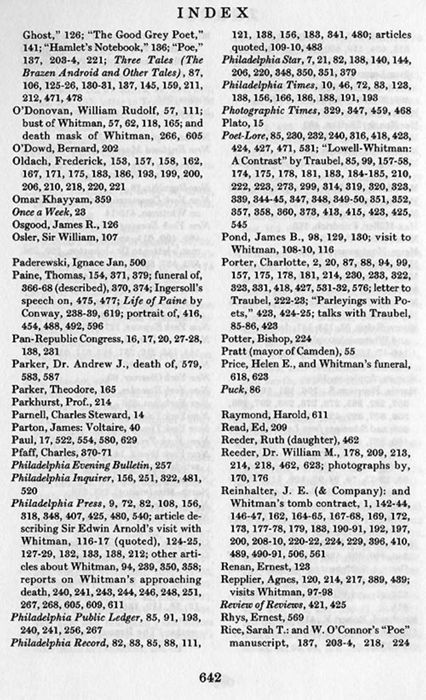

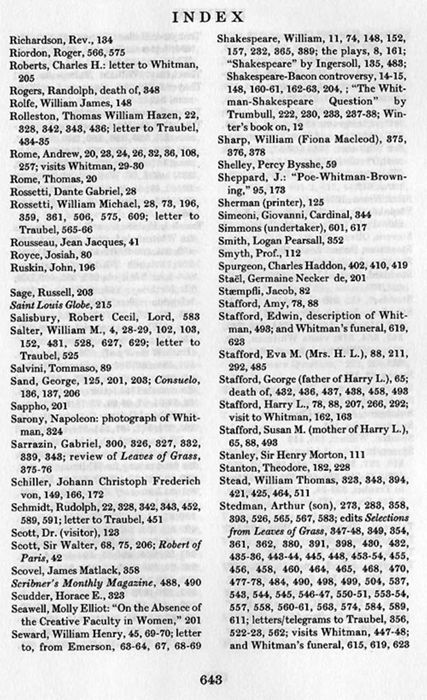

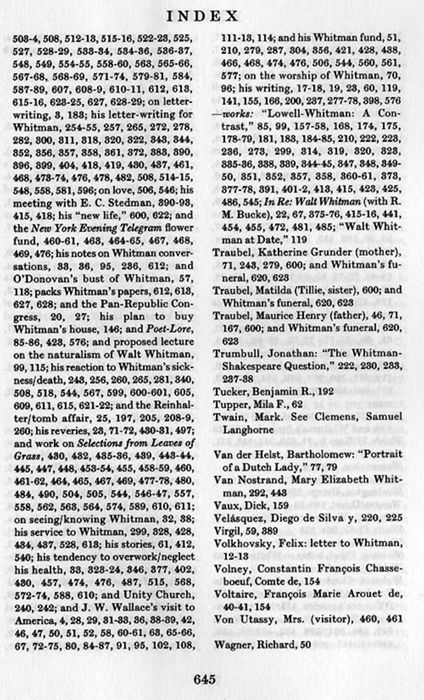

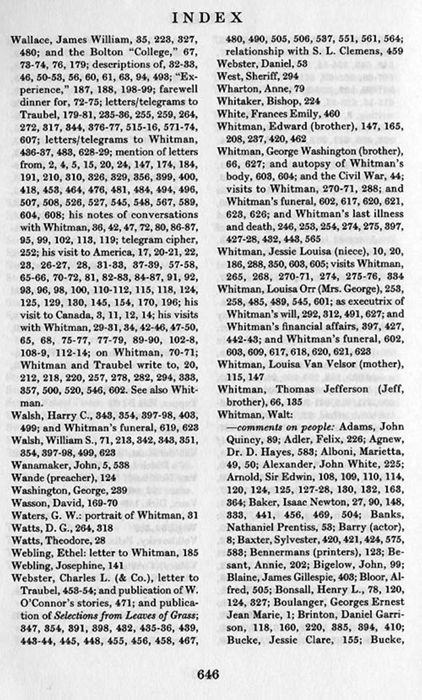

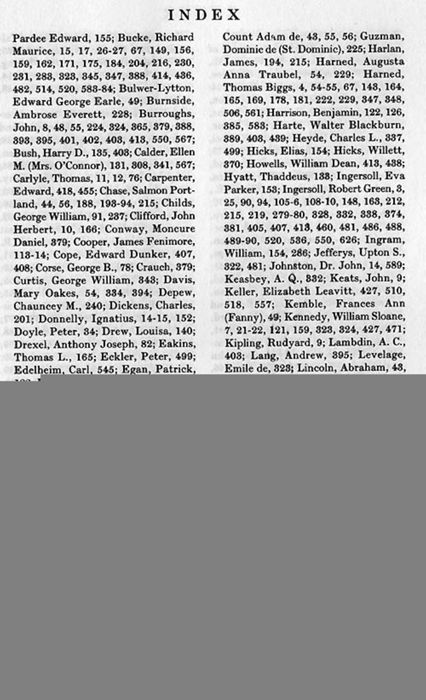

| INDEX | 633 |

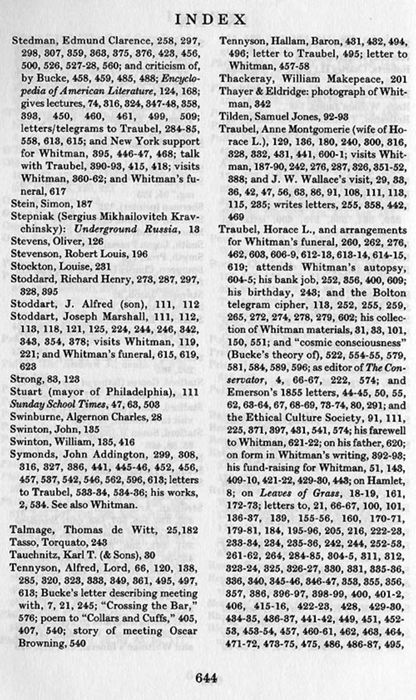

ILLUSTRATIONS CONTAINED IN THIS VOLUME

[Frontispiece]

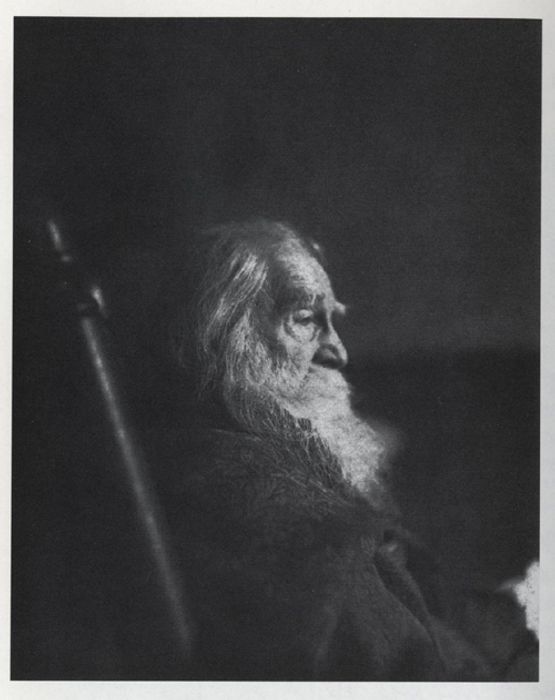

HORACE TRAUBEL, 1919. Courtesy Library of Congress, Horace L. Traubel Collection.

[Following page 240]

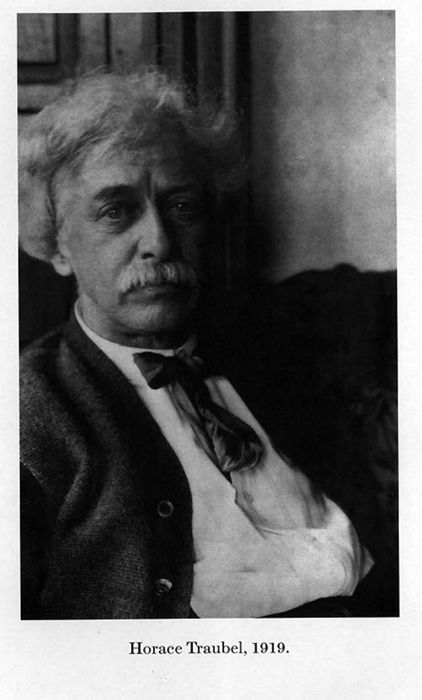

FACSIMILE OF LETTER - WALT WHITMAN TO DR. JOHN JOHNSTON, BOLTON, ENGLAND, FEBRUARY 6 AND 7, 1892. Courtesy Library of Congress, Feinberg Collection.

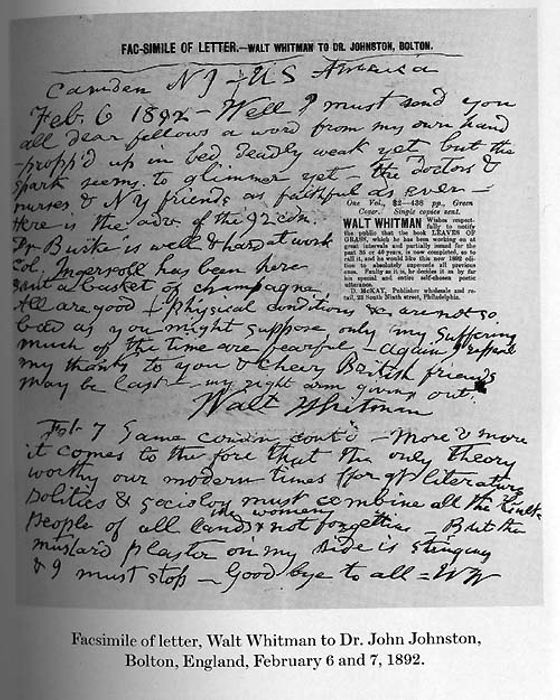

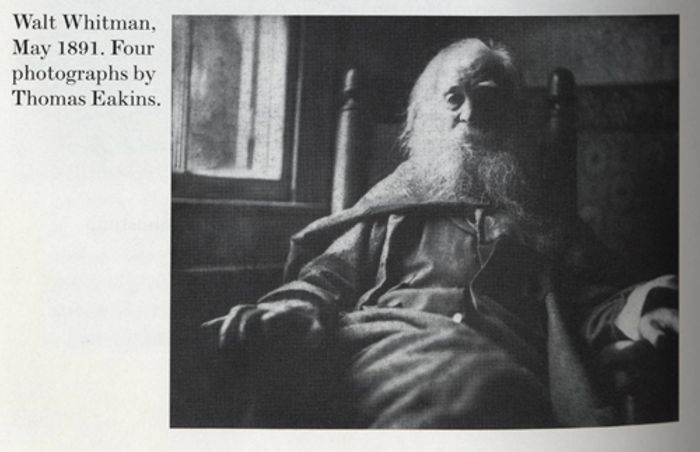

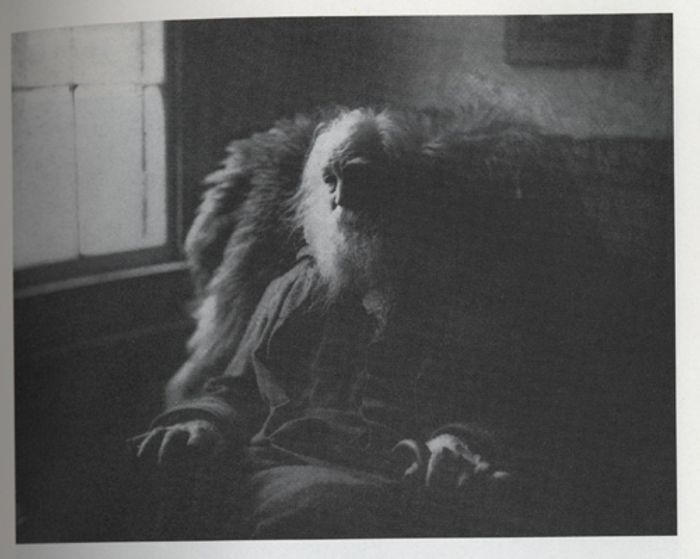

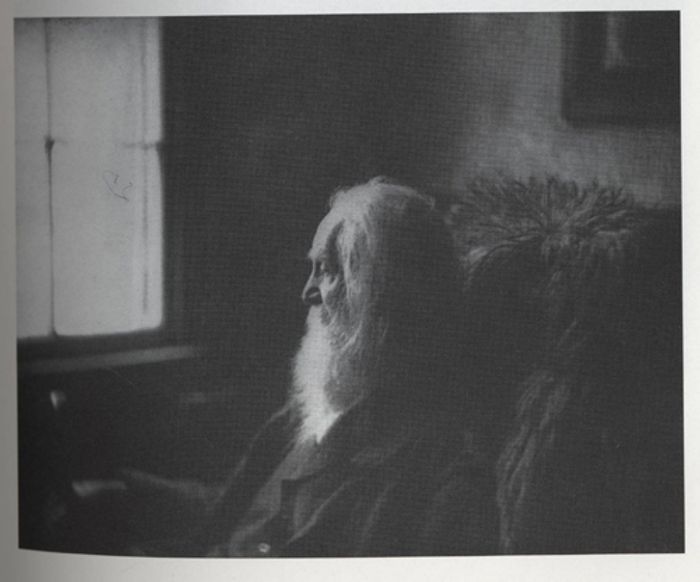

WALT WHITMAN, MAY 1891. Four photographs by Thomas Eakins, Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

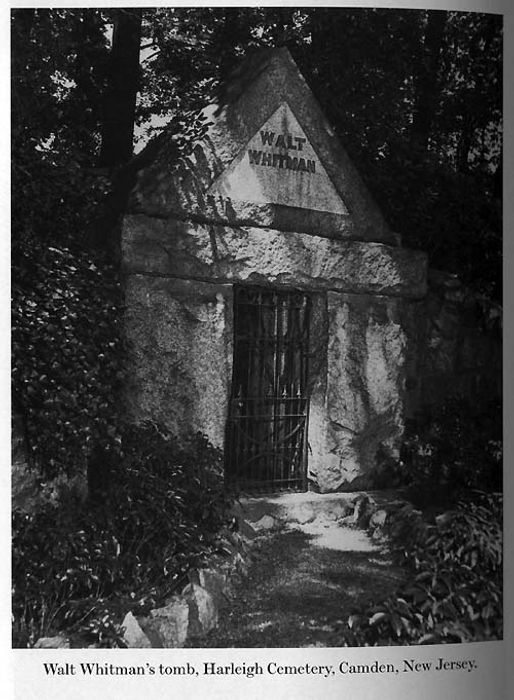

WALT WHITMAN'S TOMB, HARLEIGH CEMETERY, CAMDEN, NEW JERSEY. Courtesy Whitman House, Camden, New Jersey.

[Facing page 630]

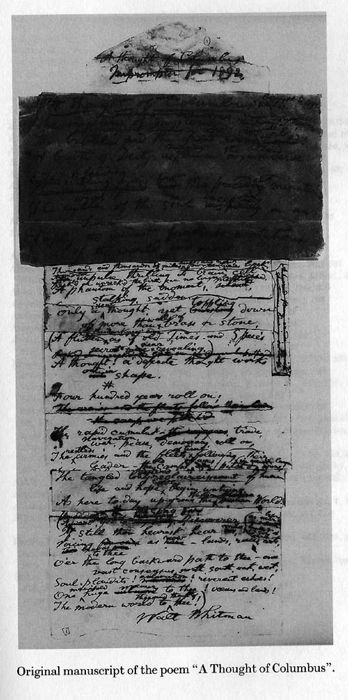

ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPT OF THE POEM "A THOUGHT OF COLUMBUS", 1892. Courtesy Library of Congress, Feinberg Collection.

LETTERS CONTAINED IN THIS VOLUME

(Including Other Manuscripts of Walt Whitman)

| Baker, Isaac Newton, 261-62, 441-42, 475, 503-4 |

| Bucke, Richard Maurice, 21, 66-67, 101, 155-56, 184, 205, 216, 234, 252-53, 304-5, 312, 325, 326-27, 346-47, 372-73, 396-97, 398-99, 415-16, 421-22, 429-30, 457, 462, 473-75, 522, 528-29, 563, 579-81, 584, 610, 610-11 |

| Burroughs, John, 254, 323-24, 377-78, 401-2, 422-23, 464, 471-72, 548 |

| Bush, Harry D., 336 |

| Calder, Ellen M. (Mrs. O'Connor), 136-37, 624-25 |

| Carpenter, Edward, 207, 416-17, 452-53, 486-87 |

| Clarke, William, 569-70 |

| Clifford, John Herbert, 628 |

| Creelman, James, 460-61 |

| Dowden, Edward, 449 |

| Dwight, Harry L., 186 |

| Emerson, Ralph Waldo, 64 |

| Evans, Leo C., 476 |

| Fairchild, Elisabeth N., 244-45, 304, 345-46, 428, 608-9 |

| Forman, Henry Buxton, 5-6, 171-72 |

| Garland, Hamlin, 264, 340 |

| Gilchrist, Herbert Harlakenden, 536-37 |

| Gilder, Jeannette L., 612 |

| Gilder, Richard Watson, 508 |

| Gould, Elizabeth Porter, 616 |

| Greenhalgh, R. K., 567-68 |

| Hawkins, Walter T., 513-14 |

| Holdworth, J. E., 417 |

| [Begin page x] Howells, William Dean, 355 |

| Hyatt, Thaddeus, 139 |

| Ingersoll, Robert Green, 160, 245-46, 311, 330, 335-36, 353, 400, 444-45, 486, 549, 595 |

| Johnston, Dr. John, 100, 170-71, 386, 512-13, 568-69, 587-89 |

| Johnston, John H., 383, 558-59, 607, 629 |

| Kennedy, William Sloane, 159, 245, 357, 615-16 |

| Law, James D., 195-96 |

| Lazarus, Josephine, 336 |

| Longaker, Dr. Daniel, 627 |

| McDowell, William O., 231 |

| Morse, Sidney H., 233-34, 623-24 |

| Porter, Charlotte, 222-23 |

| Roberts, Charles H., 205 |

| Rolleston, Thomas William Hazen, 434-435 |

| Rossetti, William Michael, 565-66 |

| Salter, William M., 525 |

| Stedman, Arthur, 356 |

| Stedman, Edmund Clarence, 284-85, 558, 613 |

| Symonds, John Addington, 533-34, 534-36 |

| Tennyson, Hallam, Baron, 457-58, 495 |

| Volkhovsky, Felix, 13 |

| Wallace, James William, 179-81, 235-36, 376-77, 436-37, 515-16, 571-74, 628-29 |

| Webling, Ethel, 185 |

| Webster, Charles L. (& Co.), 453-54 |

| Whitman, Walt, 630 |

| Williams, Talcott, 607 |

EDITORS' PREFACE

The publication of this book completes the series, With Walt Whitman in Camden, ninety years after its author, Horace Traubel, published the first volume. Traubel began his records of daily conversations with the poet in 1888, and continued until Whitman's death four years later. In his foreword to Volume 1, he wrote:

Did Whitman know I was keeping such a record? No. Yet he knew I would write of our experiences together. Now and then he charged me with immortal commissions. He would say: "I want you to speak for me when I am dead." On several occasions I read him my reports. They were very satisfactory. "You do the thing just as I should wish it to be done." He always imposed it upon me to tell the truth about him. The worst truth no less than the best truth.... So I have let Whitman alone. I have let him remain the chief figure in his own story. This book is more his book than my book. It talks his words. It reflects his manner. It is the utterance of his faith. That is why I have not fooled with its text.... It occurs here in the rude dress natural to the incidents that produced it. I had no time then to polish. I have had no disposition since to do what I had no time to do then.... Whitman was not afraid of the man who would make too little of him. He was afraid of the man who would make too much of him.... I have never lost sight of his command of commands: "Whatever you do do not prettify me."

Like the editors of the previous volumes--Anne Traubel, Gertrude Traubel, Sculley Bradley, and William White--we have presented Traubel's manuscript as it was written. In a few cases, a word or phrase has been inserted in brackets to complete an otherwise unintelligible sentence, and the punctuation has sometimes been adjusted to assist readability.

[Begin page xii]The completion of this series has been a collaborative effort on the part of many people over the course of many years. We are deeply indebted to Robert Burton, director of the Fellowship of Friends; to William Bentley, the publisher; to Charles Feinberg, whose splendid collection of Whitman materials, now in the Library of Congress, includes Traubel's manuscript; and to Professor Ed Folsom, who wrote the foreword to this volume. The staff of the Manuscript Room at the Library of Congress were unfailingly helpful. Significant contributions were also made by Peter Bishop, Abraham and Susan Goldman, Judith Grace, Cynthia Hill, Kevin Kelleher, Leigh Morfit, Peter and Paula Ingle, Rosalind Mearns, and Alla Waite.

Apollo, CaliforniaJuly 1996 JEANNE CHAPMAN ROBERT MACISAAC

FOREWORD

HORACE TRAUBEL

(1858-1919)

IN HIS MARCH 26, 1892, ENTRY in this final volume of With Walt Whitman in Camden, Horace Traubel wrote that at the moment of Walt Whitman's death "something in my heart seemed to snap and that moment commenced my new life--a luminous conviction lifting me with him into the eternal." His words were prophetic: a new life did start for him, and his name would forever be bound to that of his departed master. Traubel described himself as Whitman's "spirit child" and for the next twenty-seven years he served the poet faithfully. He was the most active of Whitman's three literary executors (the others were Traubel's brother-in-law Thomas Harned and the Canadian psychiatrist Richard Maurice Bucke); he founded, edited, and published The Conservator, a journal dedicated to keeping Whitman's works alive; he issued his own Whitman-inspired poetry and prose in three large volumes; and he carried on a tireless correspondence with Whitman enthusiasts around the world, weaving together an international fellowship of disciples who worked to ensure Whitman's immortality.

He also began transcribing his notes of daily conversations with Whitman compiled during the final four years of the poet's life, publishing three large volumes of them (in 1906, 1908 and 1914, respectively) before his own death and leaving behind manuscript for six more. His dream of having all of his notes in print--a dream deferred for eighty years--is finally realized with the publication of Volumes 8 and 9, appearing more than a century after they were written.

Only thirty-three years old at the time of Whitman's death, Traubel had already known the poet for nearly twenty years. [Begin page xiv] "Walt Whitman came to Camden in 1873," Traubel recalled, "and I have known him ever since." Born and raised in Camden, New Jersey, Traubel first met Whitman soon after the poet--recovering from a severe stroke and depression over the death of his mother--came to live in his brother George's home. The Traubel family had known George Whitman for some time before Walt arrived, so it is not surprising that neither Traubel nor Whitman could recall their actual first meeting, which remained for Horace "one of the pleasant mysteries." Traubel was then only fourteen years old, but he quickly became a comfort to the half-paralyzed writer. Whitman once reminded Traubel:

Horace, you were a mere boy then: we met--don't you remember? Not so often as now--not so intimately: but I remember you so well: you were so slim, so upright, so sort of electrically buoyant. You were like medicine to me--better than medicine: don't you recall those days? down on Steven's Street, out front there, under the trees? You would come along, you were reading like a fiend: you were always telling me about your endless books, books: I would have warned you, look out for books! had I not seen that you were going straight not crooked--that you were safe among books.

Traubel's own recollections of those early meetings were similar: "My earliest memory of Whitman leads me back to boyhood, when, sitting together on his doorstep, we spent many a late afternoon or evening in review of books we had read."

In those first talks, Whitman rarely spoke of his own work; he and young Horace discussed instead Byron and Emerson and what Traubel would later call "the details of the lore of the streets." Like the poet, Traubel had stopped going to school by the age of twelve, and thus received much of his advanced education at Whitman's hands. He began to work as a newsboy and errand boy, and on his travels around town he would often meet the poet "strolling along the street, or on the boat," or, frequently, under the shade of the trees in front of George Whitman's house, where the poet occupied a room on the third floor. At first, the boy's relationship with Whitman caused something [Begin page xv] of a scandal; Traubel recalled that neighbors went to his mother and "protested against my association with the Ôlecherous old man' " and "wondered if it was safe to invite him into their houses." Such sentiments simply drew the young boy even more strongly to the old poet: "I got accustomed to thinking of him as an outlaw." Whitman, in return, admired what he called Horace's "rebel independence."

Following in the footsteps of Whitman, Horace spent his teenage years learning the printing trade and newspaper business. He became a typesetter, and employed his compositor's skills throughout his life, often setting the type himself for his various publications. By the time he was sixteen, he had become foreman of the Camden Evening Visitor printing office. After that, he worked in his father's Philadelphia lithographic shop, was a paymaster in a factory, and became the Philadelphia correspondent for the Boston Commonwealth. None of these jobs brought him much money, but they gave him a wealth of experience, confidence in his writing skills, and an intimate understanding of how words could be made public and effective through the labor of printing.

Whitman's "outlaw" character--his ability to think outside the boundaries of law, convention, and habit--continued to attract the intense young Traubel, who became increasingly involved with radical reformist thought and who persistently urged a reluctant Whitman to admit that Leaves of Grass endorsed a socialist agenda. Traubel was aware that many literary people thought of him as little more than "Walt Whitman's errand boy" and dismissed his writing as simply warmed-over Whitman, but he was no epigone. It is largely because of Traubel's insistence on interpreting Leaves of Grass as politically revolutionary literature that we have inherited Whitman as a radical democratic poet; Traubel was indefatigable in his support of Whitman's work, and he made sure that all the radical leaders of his day read and discussed it. But he also knew that politically he was to the left of Whitman, and by the 1890s he had begun to carve out a distinctive identity as a writer and [Begin page xvi] thinker. "I would rather be a first Traubel than a second Whitman," he said, as he began straddling the difficult line between reverence for his master and literary independence. "Emerson and Whitman made one big mistake," Traubel once said. "They seemed to think that a man could not be at the same time an optimist and a propagandist, a passive philosopher and an active revolutionary. I believe it is possible for a man to be both."

While his own books can be read as socialist refigurings of Whitman's work, Traubel never became an "active revolutionary"; his socialism tended more toward the religious and philosophical than the political. But his journal, The Conservator, which he began two years before Whitman's death and continued until his own death in 1919, was nevertheless an influential organ of radical ideas about everything from women's rights to animal rights. Traubel saw The Conservator as a place where the various liberal societies and clubs could be brought together in active dialogue, and he requested support from everyone "to whom Liberal thought and life are sacred, and sympathy and comradeship supreme factors in religion." Eugene V. Debs, the socialist labor leader and presidential candidate whose supportive statements often appeared in The Conservator, was one of the strongest endorsers of Traubel's work:

Horace Traubel is one of the supreme liberators and humanitarians of this age. . . . Traubel is not only the pupil of old Walt Whitman but the master democrat of his time and the genius incarnate of human love and world-wide brotherhood.

Every issue of The Conservator began with one of Traubel's idiosyncratic "Collect" essays. The journal frequently contained one of his Optimos poems, and in virtually every issue there would be essays on Whitman, reviews of books about Whitman, digests of comments relating to Whitman, advertisements for books by and about Whitman. Often, Whitman would be presented as a kind of proto-Ethical Culture thinker, an exponent of vegetarianism or a prophet of modern science. [Begin page xvii] The space devoted to Whitman increased over the years, and by 1902 Isaac Hull Platt, in a blurb printed on the back cover of the June issue, professed to admire The Conservator "because it is the continual exponent of the latest, greatest, most beautiful and sanest gospel and philosophy that the world has known--that of Walt Whitman." The Whitman who appears in The Conservator, however, had been led posthumously by his disciple down a far more radical political road than any he had traveled when he was alive.

Traubel traced his tough-minded liberalism and egalitarian beliefs not only to Whitman but to his hybrid heritage, especially to his Jewish background:

I am myself racially the result of fusion. My father came of Jewish and my mother came of Christian stock. When I have been about where Jews were outlawed I have been sorry I was not all Jew. . . . Where persecution is, there you should be, there I should be. I love being a Jew in the face of your prejudices and your insults.

But what he most liked about what he called his "half-breed" status was that it allowed him easily to transcend narrow systems of belief and affirm an expansive democracy: "I guess I'm neither all Christian nor all Jew. I guess I'm simply all human." He always retained his democratic identification with the persecuted and remained a dedicated political and intellectual radical. He kept up correspondence with countless leftist and reformist political and artistic figures, including Felix Adler, Debs, Ella Bloor, Hamlin Garland, Emma Goldman, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair. He was involved with the Arts and Craft movement and helped publish The Artsman from 1903 to 1907, espousing the belief that radical reform in art, design, and production was essential to social reform. His Chants Communal were originally printed in the Socialist newspaper The Worker, and in 1913, the Soviet newspaper Pravda devoted an entire issue to him. Three books about Traubel appeared between 1913 and 1919, all emphasizing his socialist beliefs, and all written by fellow radicals: Mildred Bain's Horace Traubel (1913), [Begin page xviii] William E. Walling's Whitman and Traubel (1916), and David Karsner's Horace Traubel (1919). All three predicted lasting fame for Traubel, but no books about him have appeared since, with one significant exception: Alla M. Liubarskaia's Horace Traubel, written in Russian and published in Moscow in 1980. This book examines Traubel from a Marxist perspective, demonstrates that Lenin read and admired him, and celebrates him as a writer whose views are in accord with those of Lenin and Maxim Gorky.

Traubel's radicalism did not come without cost. His one stable, salaried position was as a clerk in the Philadelphia Farmers' and Mechanics' Bank, a job he began during the last years of Whitman's life and held until 1902. In that year he published an attack on George Frederick Baer, J. P. Morgan's agent and the president of Philadelphia-area railroad and coal companies, who had become a symbol of business arrogance because of his refusal to negotiate with labor unions. Traubel's employers, embarrassed by their employee's attack on the powerful Baer, threatened to dismiss him unless he gave up his writing and editing of The Conservator. Horace resigned and began a life of self-imposed poverty. He had learned from Whitman that the freedom to express unconventional and revolutionary views entailed material sacrifice; as Horace put it, "I have no right to do unpopular things and expect the popular returns." So, like Whitman during the years Traubel knew him, Horace began living on the meager proceeds from his writings and gifts from his supporters.

Since he had his own family to sustain, his reduced means affected them as well. His small family was a contrast to the large one he grew up in (he was the fifth of seven children). Traubel had married Anne Montgomerie in Whitman's home on May 28, 1891, and their daughter Gertrude was born the following year; her birth in the same year as Whitman's death signalled the remarkable co-joining of commencement and conclusion, birth and death, that Whitman had taught Traubel to expect throughout life. The next year brought the birth of a son, named Wallace in honor of J. W. Wallace, a Whitmanite from [Begin page xix] Bolton, England, who had visited Camden in 1891 and stayed with the Traubels. Anne was so taken with their English visitor that she insisted on naming the baby after him, and Horace concurred. The Bolton group that Wallace represented became the first link in the international organization of Whitman followers that Traubel was forming.

But the next decade brought harsh trials. In January of 1894 a fire severely damaged the Traubel's house, and Horace was momentarily seized by the fear that all of his Whitman materials, including his notes of his conversations with the poet, had been lost. On February 27, 1898, young Wallace Traubel died of scarlet fever soon after Gertrude had recovered from it; on the front page of that month's Conservator appeared a quotation from Whitman's "Song of Myself": "The little child that peep'd in at the door, and then drew back and was never seen again." Horace's and Anne's heart-rending letters to J. W. Wallace about their son's illness and death (now housed at the Bolton Metropolitan Library) reveal that, even when facing the horror of their child's death, they sought to learn and to grow from the experience. "Is it only through such agony that consciousness is perfected?" wrote Anne to her English friend, trying to harvest hope from her grief even while admitting, "I am a mother, dear Wallace, and no stoic." The pain continued to mount: three months after Wallace's death, Horace's beloved father Maurice committed suicide. Then, in 1902, just before relinquishing his job at the bank, Traubel received word that his friend and co-executor Dr. Bucke, with whom he had just completed editing the ten-volume Complete Writings of Walt Whitman, had died after suffering a fall on the icy veranda of his home in London, Ontario.

Horace refused, however, to allow personal tragedy to drain his optimism and energy. He enlisted his wife and remaining child in his causes. If they were going to be poor, they would at least be poor together. Anne recalled that when she had first read Whitman's works in 1889, they "meant nothing" to her, but at Horace's urging she tried again and in 1896 she became [Begin page xx] enraptured by the "pulsating, illumined life" she found there; she was converted. Anne became associate editor of The Conservator in 1899, and Gertrude, whom Horace and Anne educated at home, joined the staff of the journal as an "Associate Worker" in 1906, when she was fourteen. A remarkably talented young woman who became an active suffragist, accomplished vocalist, and respected voice teacher at the prestigious Germantown Academy in Philadelphia, Gertrude eventually joined with her mother in preparing Volume 4 of With Walt Whitman in Camden (edited by Sculley Bradley) for publication. After Anne's death in 1954, Gertrude transcribed and edited Volume 5 on her own and worked on Volume 6 until she was too ill to continue. She died in 1983 at the age of 91.

Traubel founded the Walt Whitman Fellowship International and served as its secretary/treasurer from 1894 until a year before his death. He was instrumental in founding Whitman Fellowships in other cities, and the chapter in Boston became particularly important to him, for there he met Gustave Percival Wiksell, a dentist who was president of the Boston Fellowship.

Traubel's life was filled with intense friendships, but his relationship with Wiksell, five years his junior, was the most passionate of them all. In a heated correspondence spanning five years (1899-1905), Traubel and Wiksell poured out their love for each other, often expressing themselves in Whitman's "Calamus" terminology: "Percival, darling, my sweet camerado," wrote Traubel in 1902, recalling a recent meeting with his friend:

We walked together as in a dream--a dream. God in hell! The dream is the real & the real is the dream. Definitely sweet was one hour & the next while we remained there in love's carouse--That day will go with me into all eternities. Send me your words, dear love--your words live. They go into my veins. I do not put you away with a kiss. I hold you close, close, close!

Wiksell and Traubel often met Peter Doyle in Boston and Philadelphia, reconnecting the poet's closest comrade to the Whitman circle, and, upon learning of Doyle's death in 1907, [Begin page xxi] they wrote consoling letters to each other. Horace posed with Wiksell for photographs that imitated the photos of Doyle and Whitman. The final article in the final issue of The Conservator (June 1919) was written by Wiksell, and Wiksell presided at Traubel's funeral.

For the decade after Traubel quit his bank job, he lived an energetic life. He would read most nights until 4 or 5 a.m., then sleep for four or five hours. Each morning he would take the ferry to Philadelphia and work in his garret office on Chestnut Street, where he would write letters, edit The Conservator, and set type. He met regularly with a group of fellow radicals at a Market Street restaurant, his own version of Pfaff's, Whitman's bohemian beer hall. Like Whitman, he loved crowds, and could often be found at baseball games or concerts or on the ferry, absorbing the energy of the masses. It was while riding the Camden ferry in 1909 that Horace faced his first major physical trauma: he was trampled by a horse and suffered severe rib injuries. By 1914 his health had become a major concern, as rheumatic fever had left him with a weakened heart. The outbreak of the Great War was particularly wrenching for this pacifist and believer in universal brotherhood, and over the next few years he declined steadily, suffering his first heart attack in June of 1917, the night before Gertrude's wedding in New York. He suffered additional heart attacks during the next year, and in the summer of 1918, he had a cerebral hemorrhage and was confined to his home. At this point few of his friends expected him to live more than a few weeks.

But with the centenary celebration of Whitman's birth on the horizon, Traubel's notorious stubbornness came into play: he refused to die on any but his own terms. He and Anne moved to New York in the spring of 1919 to be close to Gertrude and their new grandson. They stayed in the home of their good friends David and Rose Karsner, whose five-year-old daughter, Walta Whitman Karsner, brightened Traubel's last months. Horace sat at a window looking out on the East River and over to Whitman's Brooklyn. He ate at the very table that his old [Begin page xxii] friend Eugene Debs had used while in prison--Karsner, who wrote Deb's biography, had procured it and made it available to Traubel. On Whitman's birthday he attended the celebration at the Hotel Brevoort on Fifth Avenue and was given a standing ovation by the two hundred Whitmanites in attendance, after which Helen Keller, meeting Traubel for the first time and touching his lips to understand his words, spoke movingly of this "great Optimist" and "his scheme of a better world." He was pleased to hear speeches that night celebrating Debs and Emma Goldman; his many efforts to bring Whitman and the radicals together seemed at this moment to have succeeded.

There was yet one more centenary event that Traubel was determined to attend--the August dedication of a mighty three-hundred-foot granite cliff at the Bon Echo estate in Canada, to be named "Old Walt" and inscribed with Whitman's words in giant letters. The dedication had been arranged by the Canadian branch of the Walt Whitman Fellowship, and Traubel saw it as a sign of the growing international reverence for Whitman. The frail Horace sat in a specially constructed chair on a rowboat that took him across a lake to the base of the giant rock, where he and Flora MacDonald Denison, the owner of Bon Echo, placed their hands on the spot where the inscription was to be and intoned the words "Old Walt."

For the next few days Traubel struggled through dinners, receptions, speeches, and meetings at Bon Echo. He wrote David Karsner in New York: "Here safe. Tired. Hopeful. . . . Tired still. Damned tired. God damned tired." Flora MacDonald Denison wrote that on August 28th Horace, while sitting in a tower room where he could look out on Old Walt, rapped his cane and shouted that Whitman had just appeared above the granite cliff "head and shoulders and hat on, in a golden glory--brilliant and splendid. He reassured me, beckoned to me, and spoke to me. I heard his voice but did not understand all he said, only 'Come on.' " Following this Traubel began to fail quickly, suffering yet another cerebral hemorrhage, and took to his deathbed, nursed continually by Anne. On September 3rd Flora was sitting next [Begin page xxiii] to his bed when Traubel claimed he heard Walt's voice again: "Walt says come on, come on." Anne stayed by his bedside, held his hand, smiled, and repeated, "No regrets, Horace." In her account of her husband's death, written to J. W. Wallace, she does not mention visitations from Walt. She recalls only that, on September 8th, "he didn't drift, he went":

Afterwards, he had a very tender and beautiful expression, not as if he had less spirit but as if he had more. There was in fact very little flesh left--but he did not look shrunken, or wasted. He looked exceedingly young. Even then as he laid on the bed unmoving he drew love from my heart. Even then he made the great affirmation. He devoted himself to the art that is life--and to the life that is love--and he has made love as common as bread.

Once again, beginnings and endings fused: Traubel's death one hundred years after Whitman's birth emphatically closed the first Whitman century. But before he departed, Horace left behind a final poem, written for the dedication of Old Walt. In this poem he did what he had done so well for so long, what he had recorded in nine large volumes. He sat down and talked, one last time, with Walt Whitman:

Well, Walt, here I am again, wanting to say something to you:

In a strange place, at the considerable north, talking again:

. . .

I just feel like as if I was having another chat with you

as you sit in the big chair and with me in the bed opposite:

Oh! those blessed times, Walt! they're sacreder to me than

the scriptures of races:

They're the scriptures of our two personal souls made one in a single supreme vision:

That's all for this moment, Walt: but it's the whole

world of appearance and illumination, for all that.

June 1996

"As to 'Leaves of Grass' I can say--with all its spirit and naturalness, and as the thing blows--the wind blows--that is not the whole story. Spontaneity--spontaneity: that's the word, yet even that word needing to be used after a new sense. I am quite clear that I have broken a way--that I have indicated a path--a new, superiorally new, travel-road heretofore not trod by man. Some one of the German philosophers had said, life is not an achieved fact, but a becoming. And 'Leaves of Grass' is much like life in that respect."

W.W. to H.T., November 23, 1891

Thursday, October 1, 1891

5:40 P.M. W. resting on his bed—the night dark—seemed to be quite well. Queer, his inconsistent feelings—some days leading him to close his room to suffocation (hot days) and now, when it is cool, lying there, with two windows thrown open and the air really chill. When I spoke of this, he replied, "It is no doubt as you say, and yet I do not feel any danger in it. You see, I am well wrapped, and there is no draft here." Felt disturbed—I could see it in his manner—and found that it was because Reinhalter had been in with his bill. W. "not prepared" to pay: argued they had promised to wait a year if he paid them a thousand dollars, as he had done. No definite outcome except discovery on part of the strangers that W. can be driven to do nothing. W. said, "I will write you later on." Rarely speaks of the tomb nowadays. Is conscious, I think in a way, that his friends suspect its consistency and wisdom. Boulanger's suicide in Switzerland stirs things. W. however declares, "What had that man for us? He never seemed to me to have a reason for being: was a rallying head for discontent, wild opposition: did not seem to stand for, represent, anything. France, the world, will not miss him. Of course, the thing is tragic, dark—has its sad side—is invested with an air we cannot escape—must count. But the man is well done his days: he struck no indispensable, even valuable, note." W. again speaks of his "writing days" as [Begin page 2] over—"the sun of all that is set"—though his after-light, the math of things been, may last him "a while yet"—though "from day to day" he faces the august shadows, fearing nothing—"prepared, ready, to break the last tie." Rather moved me to find him in such a mood, though his dominating cheer soon broke through, to show that he was sound as ever at core. "Not a letter today: hardly a glimpse of the outside world, even from the papers." Had written no letter, "perhaps" would "in the evening."

Friday, October 2, 1891

To W.'s on my way home—5:45—but found he had just closed his blinds and meant to lie down. I did not wait—had no mail. Not a letter written. "I doubt if I have written a word for two days." Seemed for some reason not so bright.

7:55 P.M. To W.'s again. In his room, reading Hedge's "Prose Writers and Poets of Germany." "It is one of my resources." Harned had been in last night. They had talked considerably about Symonds' essays. W. disposed more and more to give them value. Yet Miss Porter asks me, as I read her Symonds' letters, why this difference in temperature, the published as against the private judgment? Was it the consciousness of the critic? W. believes, "Yes, there seems no other way out. For sincerity lurks in both—is present everywhere."

W. says still, "I hear from Wallace, no less than two letters today. And a letter from Dr. Johnston, too, written from Annan, Carlyle's old place. Oh! There must be a charm in it all! Johnston has gone there to see his parents—was born there. The parents seem quite well-ado—solid, of some local consequence. I enjoy the Doctor's letters, especially some of them. He has at times an objective touch—a daring objectivity—gives description, detail. I am greatly moved by it." Was this letter one of the sort? "No, I can hardly say it is. The letters from the fellows there—from Johnston, Wallace—are mainly made up of thankfulness to me, to my work. Yet Wallace, too, now and then, tells [Begin page 3] me what he sees, leaving the thought of what he sees mathunsaid. This shows power—too latent, too little exercised, perhaps." Reference to Emerson, Carlyle—some of the old fellows. "They evidently made drafts of their letters (does Wallace? you think so?), and I don't know but that has something to be said for it." I argued, however, "Letters, journals, should be free: float along, word by word, as it comes, like the toss, the rhythm, of a song." W.: "Beautiful! I like that. I guess it is so! I live it—our fellows would, naturally. But I often look at the letters of the old fellows—say, a hundred years ago—they have a certain stateliness, measure—preparedness—yet a charm, too." I asked, "What of Bob's letter the other day?" "It is perfect; it is the curve and sweep of a wave up the shore!" Adding, "But every one to his kind. And we must see to it, every fellow is acknowledged for what he brings, not what we think he should bring." And again, "A letter is very subtle! Oh! The destiny of a letter should be well-marked from the first. We should know, make, every letter to fit its purpose—to go to the doctor, to the intimate friend, to the admirer, and so on and on, each having a quality its own, and for a specific end. It may seem queer for me to have a philosophy of correspondence, but I have. And of course, freedom is the charm of a letter—it before all other qualities. And a letter without freedom certainly has nothing left to it."

I had a note from J.W.W. marked Lindsay, Canada. W. said, "I am not surprised that the expansiveness, bigness, of things here should storm him. It gives him a copious draught. But what of his return—not a word of date?" I expected him any time next week. W. asked, "But you know nothing about his dates?" Speculated about Bucke. Is the lecture over? Was it a success? I was to go to Unity Church to hear a lecture on Hamlet. W.: "Yes, go and tell me about it." But there might be nothing to tell. W. then, laughing, "Well, tell me there is nothing: it is something to know that." Explicators of poets? I felt to say to them, Diogenean-like, "All I ask is, that you keep out of my light." W.: "A fine application, Horace, and true as truth! It is my own feeling exactly. And it is one of my dreads, that there [Begin page 4] may come a time, and people, to exposit, explicate, 'Leaves of Grass.'"

Left him a dozen Conservators. "Will send them away." Asked, "And what of the gentle, great Sidney? Is there anything further? No? What a child of nature! How could we but love him! The piece? O yes! I like that—more than like it: it is few but mighty," playing on a current phrase. "But 'Song of the Open Road' for Sidney? I can't find it anywhere. Very likely we will send him a complete book—that might be best." Salter wrote of his "pleasure" in Morse's "Leaves of Grass" article. W.: "I do not wonder—it is as simple, sweet, as a tale told across the table." W. "doubts" if he can go out tomorrow. Seems able, yet disinclined. More and more withdraws. But we will try. I leave it in Warrie's hands—I to be at 328 a little after five—to go out, if W. is agreeable; not, if not.

Wallace's letter of 23rd in a grateful strain, no objective eye evident. In letter of 28th, writes of plans of his departure on the morrow.

Bucke writes (27th), about to go to Montreal. Speaks of J.W.W.'s departure, will miss him, etc. Had no copy of address to send us.

W. gives me Wallace's letter of 17th to illustrate "the, so-to-speak, inner tones of the man."

Saturday, October 3, 1891

5:10 P.M. W. could not go out. Says at once to me, "I feel blue—bad." I protested, "I thought you never felt blue." To which, "It is as well not to be too sure of that." Going on, "I have been depressed. I don't know for what: for several days, now, in a cloud. Yet the days themselves have been fair and beautiful! But prisoned here—cabined up—it would be hard to see only cheer and light—only the rosy side of things." Spoke of Mrs. Davis as "still under the weather." Again a word of Harned's visit the other night. "I was glad to see him. He is a rush of vigor: stirs me." Then, "Another letter from Wallace, [Begin page 5] this from Fenelon Falls. He goes on at length about Fred Wild—some tragedy in his life, maybe. And part of him left in this place, or there once, and now memoried. The good Wallace! In this letter rather more than in others he gets out of himself: a quite important thing, especially for a strong man." Then, "Here is the note. You might as well take it"—slinging clear over the table to me.

I too have note from Wallace, but 'tis merely general—very short—and to about the same effect. W. likewise gave me Forman's letter at last: 46 Marlborough Hill St. John's Wood London N.W. 8 September, 1891 That birthday bit in Lippincott is a capital thing and most satisfactory for friends overseas who wanted some direct words, and evidence as to health, etc. Friend Traubel has done his photographing well and deserves our thanks. Conway's is the only bit that reads just a little stilted and as if written with one eye turned inwards and the other one half on you and half on the public. Well, well! now this is not very charitable, and after all it's a jolly, hearty, manly crowd that we see through Traubel's pages gathering around your revered form, dear Walt Whitman. Last time I wrote I was going to the Vienna Postal Congress. Since I came back I have had Bucke staying with me and giving me all the last news of you and renewing old memories (grand times!); and while I was there at Vienna I met "An Americano (not) one of the roughs," but one who knows you. This was William Potter of Philadelphia, who was one of Wanamaker's delegates to the Congress—one of the United States' delegates, to speak strictly. He is a real good fellow: he was the best friend I made at the Congress this time. The money I'm sending in this letter (about 15 dollars) is chiefly for "Good-Bye, My Fancy!" which I am without, though I have seen Bucke's copy. I want a copy in cloth as issued, with your name and mine in it if the old indulgent mood holds, and two copies of the untrimmed sheets not bound. Then I want, if it is to be had, six copies [Begin page 6] of "A Backward Glance" as printed on thin paper to be annexed to "Leaves of Grass" (pocket book edition). They need not be stitched or done up any way, but on one I should like your name and mine on the title leaf. There are several minor works, or rather separate works, which I fancy you still have, and of which one copy each similarly inscribed would be very welcome: these are "Passage to India," "Democratic Vistas," "After All," and "As a Strong Bird." Lastly, my youngest son, Maurice Buxton Forman, is likely to go out into the world soon—most probably to Egypt. He is now nearly 20. When he goes I want him to have the big book—Complete Poems and Prose; and if it were attached to him by your own hand in the same way the effect on his mind would be good. He is studiously disposed, and it is about time he began on the "Leaves": indeed he has begun. So I want to buy him his copy, for a part of his essential outfit, whether you write on it or not. Now if it chances that you do all I am asking, and the money does not run to it, as well might be, the mention of the figure minus will bring the rest by first post. Ever in affectionate respect H. Buxton Forman Repeated his notion that its characterization of Conway's letter was not just, yet that the letter (Forman's) was "genuine, noble." And, "You ought to have it for what it says of you—words to remember, keep." To him, "Forman must be a grand companion—a grand fellow to know."

We spoke of Young (J. R.), W. remarking, "John is a fine make-up: one of the best journalistic samples—German, strong, with a vivid style. He has always made me near his heart—held me close for good words, demonstrations. What I like about his references—well-sampled in that in the piece on Conkling—is his confidence. He makes no apologies—mentions, states, is free and full, says his say, lets there be no doubt about what he means—then stops. Does not appeal, does not argue for, best of all, does not apologize. Which shows not only the true artist-eye, but nature's." And further, "Shows a true appreciation of the situation," for we are "to be received or rejected and the devil take the rest!"

[Begin page 7]Had W. sent the Star to Bucke? I had left copy. "Yes, I sent it. Does he say it never came? Yes? Why, I am sure I have somewhere his acknowledgment of it. And yesterday I sent him the other paper." What other? I knew no other. "Oh! Did I not tell you? I meant to. The Transcript. And I want to say, too, I don't quite get at Kennedy: he is a queer fellow—turns odd corners. Here in the Transcript is a paragraph—undoubtedly written by him—in which he says that the writer has seen a letter written by an American gentleman visiting Europe who had seen Tennyson, etc., and then goes on to give the awful story. Wrong! Yes, wrong! Kennedy is guilty of trespass. It ought to have been clearly understood by my letter and by Doctor's itself that there was to be no publicity given anything which the Doctor had sent us. And yet Kennedy quotes it. It is hard to explain. Not a serious harm, I suppose, but harm—and harm if simply to give a word of it under the circumstances. Probably nothing will come of it—no evil—it may even be buried there. On the other hand we find often enough that some insane little item which never should have been written, travels the world around, into every hamlet, is denied nothing, makes ruin everywhere." And W. reflected, "Kennedy is not a fellow I can understand. At least, not this time. I don't know what Doctor will think of the breach—for breach, trespass, it was. It makes us a caution for the future. In the first flush I was a little angry about it, but I am inclined to let it go now, without a word. It is enough to know the bird is out—escaped—the damage done." Further, "And there was something else in the Transcript—a comment made upon an elegant new edition of Bartlett's quotations—and the question is asked: What is the matter, that Walt Whitman does not appear by a word, a line? I suppose Kennedy wrote that—it shows his mind, if not his hand. You think the journalists favorable to me? A good many, yes. As to magazine editors, they have a dignity to preserve—a professional something or other—and will not unbend to unusual or unpopular events. But the boys in the newspaper clans are of a natural tone, more or less able and willing to say a good word as occasion, freedom, persuades."

[Begin page 8]Did he know Barry, actor? Miss Aiken tells me her father and Barry old close friends. W.: "Yes, I remember him. Not thoroughly, not in detail, but as a person, those times. He was a man fitting well in minor parts—one of the walking gentlemen—indispensable, yet not important. There were hosts, the like of him. And sitting here these later days, inactive, having no outlet, memory panoramas the whole past, finding me a character here and there, to live again, whom I had thought gone forever even from the thought of men. The stage? I suppose there's a sense in which it has gone down—lost caste—position. But stars differ in their glory. And all we can say is, that changes have come—perhaps not all of them for the better."

Had he ever taken any extensive out-doorings with Burroughs? "None at all." Yet was it "a good experience for anyone who could companion John," who was "like a bit out of nature herself, a wild hare, the flower that grows in the wood, the bird in mid-heaven."

What had I heard last night about "Hamlet"? And then some talk thereon. Long had curiously said, "One of my doubts of Shakespeare is in the fact that no two men seem to agree as to what he meant by the plays." W. put in now, "Well, that would knock out his Bible, too." I then, "That's what I said, and all literature." And I said further, "Shakespeare did not intend to make Hamlet sane or insane, or to make his characters anything: he simply intended to make them, represent them, cutting them vividly out of life, with all their contradictions. For instance, in Hamlet: to show the conflicting conditions that warred about and in him and his resistance," etc. W. exclaimed, "That is fine, and it is 'Leaves of Grass': it is our doctrine—the doctrine we swear by," and more to the same end.

Sunday, October 4, 1891

1:30 P.M. Very hot day—I spent forenoon in Philadelphia. But W.'s condition day before, and for several days, had worried me, so made a special trip over to see how he was. Gilbert with me. [Begin page 9] Left him on step, with Warrie, while I went up to W. We talked 10 or 15 minutes together. W. reading Philadelphia Press, spoke of its "dullness." Yet that "all days here grow dull—lose their pulse, life." Indisposition to see strangers. "I am gradually closing all the avenues of escape: life narrows, narrows." Yet finds his mind still craving to know the world—to follow its winding experiences. I am to see McKay tomorrow. W. said, "Let Dave see everything is open except the simple fact that the additional pages are determined upon—that they are to go in, whatever he thinks about it. Yes, even in with the copies he has printed and in sheets. As for the rest—talk the matter over. You represent me. Tell Dave if he thinks to continue the book at two dollars, can manage to do it: well, very well. Yet that it is my notion something will have to be added. All I have to say is, feel him for the points we have talked over—then come to me. We want to be just to Dave and are determined to be just to ourselves, too. It is a closing act—the last on the bill: soon the curtain will be down."

Monday, October 5, 1891

5:40 P.M. W. reading papers. But was not well. Spoke of himself as "the same as yesterday—no change," but added, "But for the past ten days I have felt thoroughly bad, have had a bad run." Had he seen Kipling's portrait in Century? "Yes, and it seemed to me the face not of an Englishman. Oh! Did it impress you the same way? It is undoubtedly a strange face—a stranger face. Do you know, Horace, I think this fellow must amount to something. There is every indication of power—of a something there—though what I don't know. But he is very young, will probably break up. The precocious, early fellows can't, as a rule, stand the racket. True, there was Keats—poor Keats—went under, as so many thousands we do not even hear of—fragile as delicate-spun glass. I think Sidney hits the nail on the head in his little piece, what he says amounting to this, that polish is pushed to such extreme, it makes me mad. And that, you may say, is Keats. Noble Keats, too—the splendid sweet youth!"

[Begin page 10]A couple of packages for Post Office, one for niece, St. Louis, and one for Humphreys, Bolton. I laughed about the fullness of W.'s addresses, he remarking, "My friends always used to do that—do it still. But I think it a measure of safety. Once, many years ago, I sent a package to a fellow in New York, and it came back. I found on examining it that it came back because I had neglected to put 'third story' on it. Which taught me a lesson. You remember my friend in Washington with his stacks of trunks—the Adam Express man? He assured me that a little more care in addresses would have taken fully nine-tenths of the trunks to the proper persons. Now and then I get a foreign letter simply addressed 'Walt Whitman, America,' and it gets here sharply. Some knowing man in New York sends it right on."

Clifford in to see me. Has taken a reportership in Times. W. asked, "Has he anything in him for that?" I took the new sheets to McKay—had a long talk with him. He started by saying he thought the idea of the addition "foolish." I put in, "That's not a part of the discussion. They are to go in whether or not that is settled. I am here to discuss how they are to go in—on what terms." We got along amicably enough—a good deal of fencing. He opposed utterly to cheap edition, suggesting two editions: the one for two dollars, present price (autograph facsimile), the other at some larger price, with actual autograph. McKay not averse to green cover—rather favors it. Speaking of the present cover he said, "Walt insisted upon it—wanted it every way just as the Boston edition." "But you know why he wanted it so?" "Yes, I do." "And you know the reason is long since passed?" "Yes, I know that, too. I have no quarrel with the case, either as it is or as it is proposed to change it." McKay goes away tomorrow to New York and Boston and will not return till Monday. Will then be over to see Walt. W. asks, "That means the delay of another week?" "Yes." "It is our luck! But we can only smile." Then, "On first impressions, I would decide in favor of the two-dollar book. I do not insist upon actual autograph: perhaps the facsimile would serve for all." And again, "Our point is of course to add the pages. Whether we make any gain beyond [Begin page 11] that is not so important. I still adhere to the idea of the cheap paper edition. Sometime that must be. I am so happy to have lived out the work, to have touched the last mile-point (actually, I have rounded 'Leaves of Grass'), that I am willing to sacrifice most else. Though that is not sense either. But anyway, Horace, negotiations are mainly in your hands to make. We'll discuss it more or less thoroughly, day to day, before Dave is back."

Has been reading some of the Shakespeare plays. Not a word to either of us today from Wallace. "But Doctor writes me from Montreal—says the lecture affair was a great success—but not a word about Wallace." Johnston's postal from Annan moved us both. W. says, "I guess it is so. Carlyle always stirs me to the deeps. He was a giant-man, none more so, our time." McKay had called my attention to what was a defect in copyright page—W.'s assertion that in 1919 he might renew. But McKay argued he can't do it because he has no direct family—wife or child. W. however insists, "I think Dave is wrong. I have the copyright laws here and will look it up. But I am sure Dave is essentially wrong." After a pause however, "I don't see that it makes much difference either way. We'll all be dead, some of us long before that. So that it all comes to a point over which we needn't break any bones." Dave said to me, "If Walt insists on these pages, I suppose Mack'll have to take the dose!" To which I, "I'm afraid Mack will." W. said, "That seems rough, but that's about the amount of it." I found we could produce a paper-covered Walt Whitman for less than 20 cents per copy.

Tuesday, October 6, 1891

7:50 P.M. W. reading. Good color—warm hand. "It is almost winter's chill—eh?" he asked. Yet, "I stand it pretty well, supported last night by a good sleep." Then, "Now tell me the news!" I laugh at that question always, say to him, "You bring me news from the eternities: report for that today!" But he shakes his head, "No, it's time we want—the news of our own [Begin page 12] daily life—the history that is being made day by day about us." Told him then of my letter from Johnston today. Did he wish to read? "No, I guess not. Tell me about it." As to George Humphreys' book, "You were right in your guess. I sent the book yesterday." (I had "guessed" this in a letter to Johnston today.) "I held back, hoping to send him a copy of the final and complete edition. But as things hang fire, and threaten to go on doing so, I thought it better to send what I had." Then, "I have written Johnston, too, today. But no word comes from Wallace. Have you heard? He will be along before many days, no doubt, linger a few days—then, exit. And for me the last of him!" W. said this solemnly enough.

Book sale, at Thomas' today (Philadelphia). Copy of Bucke's "Whitman," presented by O'Connor to Appleton Morgan, on list. W. said, "I know nothing of Appleton Morgan, except what I gather from O'Connor. But he may have been some shakes among scholars of his kind." What of Winter's new book on Shakespeare? W. said, "I am reminded by it of what Carlyle said of modern poetry. He called it a raking over of old embers. Describes the poets—these times—poking at the old dead or dying fires—inviting them to burn—turning over and over the old ashes, for the spark of life left—finding little, perhaps nothing—chill, north-wind. That was Carlyle, and not to be too severe I would apply it to studies of Shakespeare—to Winter and his degree in particular. The critics of the great dramas all occupied to prove unprovable things—to stir up passions, fires, long gone out—the deceptive embers instinct with nothing. Oh! it is a lifeless sort of business! Yet a fellow hates to be too general, to make the mistake of being unjust. For often life comes, where we had thought of nothing but death."

W. afterward, "I have laid a letter and a paper out for you. I felt you would be interested. The letter is from the nihilist over there in London—the editor of Free Russia—and the paper will show you what sort of work he is doing. And anyway, keep both. They have an interest and value—show which way the wind blows." [Begin page 13] Henhurst Cross Beare Green, N. Dorking England. Sept. 26 1891. Revered Comrade You will be puzzled at the strangeness of the name subscribed to this letter, but you know well that democracy includes all nationalities and therefore though foreign, no name will be alien to you. Since I have been a political refugee in England, after going through America, I have met with many young people of your race, whom I admire & esteem, & who have told me the same thing—that Walt Whitman is the man who has done for them what no one else has done, has formed their character in accord with democratic ideals. And I understood this better when I became better acquainted with your writings. I also understood that the cause of justice & freedom in any country whatever could not be alien to you; and therefore I have decided to write you this letter & to send you the paper, intended to plead among English speaking nations the cause of freedom in Russia. I hope that you will find a moment to look through it & to kindly send in some lines from your mighty pen to be inserted in it. If you can aid this cause by introducing the subject among your friends & admirers & the general American public, you will do a good deed. Yours fraternally, Felix Volkhovsky Spoke of Stepniak's reputed friendship. "It is the rugged first-handers we are after." Would read "Underground Russia" if I brought it.

Left him—went downstairs—loitered with Mrs. Davis. While there a ring at the bell—Longaker admitted. After greetings we went upstairs together. W. seemed very glad to see Longaker, even said he was. And when asked how he had been said, "I have had the devil's own time with neuralgia, Doctor, for ten days past. All down this side of the head and face," indicating the left. "The night before last was a very bad night: it hardly let me sleep at all. But last night I slept well—enjoyed the peace of the just. Indeed, had an unusual sound long sleep. And stomachically I'm nothing to brag of either." Thence to questions [Begin page 14] and answers about digestion, "evacuations," as W. calls them. W. showed bad memory. Longaker tripped him several times (said to me when we got out on the street, "His memory is perceptibly failing"). Had not been downstairs today, "nor disposed to move anywhere." Longaker felt his pulse. "Is it about right, Doctor?" "Yes, just about, just." Longaker said, "I like to see you here nights. It is the time you show to best advantage." "Do you think so, Doctor? These days, to show to advantage any time is victory." Longaker said he had intended bringing copy of New York World (Sunday's) over to show Walt. A story of Kipling's there, started with quite a quote from W. Longaker "had not known Kipling was disposed our way." And W. laughed out his words, "Anyway, it's another straw on the winds: gives us a hint we won't dismiss, ignore." Longaker picked up from floor Johnston's photo of the Isle of Man, W. too much admiring. "Doctor seems to follow up the trail of beauty—gets his subjects always at the right moment."

Wednesday, October 7, 1891

5:10 P.M. To W.'s and a good talk. Neither of us have word from Wallace, but W. says, "He is no doubt all right—prospering somewhere. And though no word came, I expect him here any day now in propria persona. And of course he will be welcome. The English fellows have eminent good heart. There is nothing better." We had been startled by news of Parnell's death. W. much moved, "Now there are three: Balmaceda, Boulanger, Parnell. And all three from excitement, worry—what is called failure. Death and defeat! It is tragic. It brings up many questions."

We have news that Donnelly will speak in Philadelphia some late day the present month. W. asks, "Do you know what about? No? I often wonder about Donnelly, if he hasn't his career yet to make, or if all has been said that is to be said—can be said? His book? I have known it passably well. To me the first third or half of it is a wonderful statement—a rare, rich mass of [Begin page 15] learning, acute and conclusive. But the last, the cipher business, I have never read. Has Donnelly helped or hurt this controversy? The Baconists? I can never answer my own question—never make up my mind. Indeed, feel that only the future can settle the point. And Donnelly himself puzzles me. It is a question in my mind, whether the dash of insanity which Plato permits—even insists upon—for the poet is valuable to, does not damn, the lawyer, the critic, the advocate, the man whose bent and necessity is cold logic—close resistless indefatigable reasoning. And sometimes Donnelly figures to me possessed of that tendency—that dark shade—that taint, to put it severely."

As to his condition, W. answers, "It is only so-so." Asked me, "Is the general closed-inness of things I see out my window here prevailing in Philadelphia—on the river—as well? I suppose so. It has its curious atmospheric turns. I have been watching, absorbing, tallying it." I put in, "For much of it is mood as well as weather," to which he, "That is just what I meant in another way—with other words—to say: but you say it for me." Remarks himself the increasing distaste for work, writing. Is "glad" for "Mary's change for the better." W. said with rather a laugh, "Wallace sends me a copy of the Bobcaygeon Independent—a queer sheet—nothing being in it. Yet it comes, fragrant with the boy's good will." Gave to me. "I have no use for it," he said. "I wonder if anyone has?"

Thursday, October 8, 1891

5:40 P.M. To W.—in his room—reading local papers. Very cordial. I had but a few minutes to stay. Was all well? "Very, for me. Yet abstractly pretty bad. But we are not here to complain." Letter from Bucke? "Yes, a lively one, too. He is back, and busy. And he seems to regard his Montreal trip as a great success. Certainly, he enjoyed it, whatever of the others. No doubt it had important meanings." He thought Bucke's "opinions"—yes, "even his notions"—on these special lines "must carry great weight." I had two letters from Wallace. He is now on his way South— [Begin page 16] expects to be in New York tomorrow. W. saying, "We are then almost at meeting-point again. Well, let him come, to be"—with a laugh—"disillusioned."

The room full of smoke from the fire, yet he seemed oblivious. Even his smarting eye hardly told him. Yet on my reminder he said, "I did notice something, yet did not know what. Of course, it's bad." Yet would not let me open door or window. Chafes under McKay's delay. "Why the devil couldn't Dave have gone on. We can come to terms anytime, but the book itself ought to be out." Pan-American Congress in Philadelphia next week. "Have you your poem finished?" I asked. "What poem?" "Oh! the one announced last week or week before in the papers." "The papers? Oh! the papers be damned! A big lie in a little paper—or in a few words—will girth the world—go everywhere: the meaner the lie, too, the more perverse will people be to swear to it! But, however, tell me about the Congress, Horace. Is it all fallen through about the Colonel? Will he fail them?" But I insisted, "I am for the present interested in the poem." He then, "But I tell you there's to be no poem—from me. I am interested in the Colonel," laughing, exclaiming. For, he said, "The Colonel would set them on fire, if he were there—were to let himself out." But the Colonel is not likely to be there.

Friday, October 9, 1891

7:58 P.M. W. very cordial in his greeting. "Glad to see you again! So it is, day to day! Meet—part—meet again!" News? Who had news? His old question. Told me at once, "I have a letter from Wallace. Yes, written from Albany. He is probably in New York now, has the note you mailed him yesterday." I too had a note from Albany, 8th. W. went on, "He seems journeying back leisurely enough, which is the best way, no doubt. You don't think the Colonel will speak in Philadelphia?" "No more than that you will give a poem!" "Well, it's certain enough I shall not give a poem. In the first place, I doubt if I have been asked (I get so many requests, I forget most of them), then [Begin page 17] again, I couldn't give the poem if I could. All that is past for me." And again, "Wallace will probably be along Tuesday. He will finish on Long Island, unless you break in on him with a summons to hear the Colonel, which is unlikely."

W. then asked, "Did you get one of the printed copies of Doctor's Montreal address? Yes? It is a handsome document, don't you think? I started to read it today—did not get very far—yet far enough to see that this is probably Doctor's crowning work, probably the best writing he has ever done. But I could not go straight through it. It is a thing not to be passed lightly over, not to be dashed through with, but must be studied, page by page." And still again, "It displays considerable esprit—is quite professional. But good, apparently, every way."

I had a note from Garland. Said W., "Good! Good!" as to the first part, then, "I don't know about the book. Sure enough, did he send the money? There's a doubt in my mind! Indeed I had forgot the book—it is not sent. I remember his letter quite well, but remember nothing about the enclosure. But anyhow, I shall send the book—he shall have it." Is this W.'s memory again? It is likely. I had written Garland I would refer his note to Walt.

W. asked about Clifford, "How does he like his place? Does he fit to it? Make something of it?" Somehow we got talking of O'Connor—I don't know how. W. saying, "I tell you what, Horace, you ought to make out at some length a magazine piece about William. Any magazine ought to be glad to take it—Lippincott's, such. Though, of course, I don't know. To tell the story of William's life—what he seemed here for—what he stood for—the aim, accomplishment: that would be a great pleasure. You would thoroughly enjoy it, once started. And one point, Horace—if you write, caution yourself: do not make much this time of William's connection with me—touch it lightly—pass on. Then again, later, in other ways, have a special article dealing with nothing but that—our meeting—the eternal friendship (yes, eternal—it will, can, have no end—here, elsewhere). Your point would be to tell of that life—go into any details you chose." Someone had spoken of O'Connor as W.'s St. Paul, but [Begin page 18] W. shook his head, "Anyway, we will insist that William must be recognized by force of his own genius—does not need us, anybody, to lift, assist him—will anywhere account for himself, on his own terms." Would he help me in such a paper? "Yes, give you letters—dates—facts—add to, help you in any way." Burroughs thought there would be an O'Connor revival—a demand someday to know more of him. W. asked, "Did John say that deliberately? It is significant. I am sure it will be the case. Such superb personalities cannot be wrecked, lost, swept away, forgotten. And I think you could do a good deal even now to bring about that shift in the current. Just put the idea in your pipe—smoke it." And more, "You would want to set out the strong features of O'Connor's life just as simply as possible—to go underneath exteriors—to get the world to understand really what manner of man he was. And after that much is done the rest will easily follow. The noble William!"

In course of our talk, I said, "I often wonder if 'Leaves of Grass' does not after all and most of all mean good health." W. quickly, "How is that? Tell me how you come to ask that." "Why, it always fills me with such entire satisfaction, abandon, as a fine day. After I go from it, I find I always feel well. I find that I am large—that all my meannesses and doubts have dropped off." "Oh! that is noble! Oh! You give it a noble credit! I wish it could be so! Yes, I do!" "But it is so for me: that I am positive enough of." "But what of others? Develop it for me, Horace." "My judgment of a book is not by its ideas, or its sections or chapters, or its ornateness, but by the condition in which it leaves me. And 'Leaves of Grass' always leaves me whole, aspiring, full of courage." "A splendid criterion: I know none better! Tell me more of it, Horace." "There is no more—isn't that enough?" W. with a smile, "Sure enough—enough: if only it were justified." I adding, "Some books make me feel mean, small—the worm that never dies—make me ask why the devil I came and am alive anyway. But 'Leaves of Grass' expands me—makes me feel limitless. Yes, it fills, crowds, me, like a great grand day!" W. exclaimed, "O proud fame! If this should [Begin page 19] ever come to the 'Leaves'! And anyhow, Horace, you have touched a deep chord. I feel in it the throbbing life of a great thought. I hardly think you know yourself how deep you have sounded. Who knows? I guess there is no longer line." I mentioned Hawthorne, "He leaves me oppressed; 'Leaves of Grass,' glorified." "Does Hawthorne have that effect?" And several times he declared, "You have opened my eyes to the best future I can see for the 'Leaves.' To leave men healthy, to fill them with a new atmosphere." Then hauls himself up suddenly, with a laugh to me, "But what proof have you of it anyway?" And shakes his finger at me, "Be careful of your claims—guard your retreat well. For after all"—relapsing to quiet, thus abruptly—then resuming—"Yet William and I used to claim everything (like the politicians), at least set our claims way towards the top!" This reminded him of something, "If you write about William, write a good deal about his Lincolnianism. Tell how he came upon the significance of Lincoln at the jump. Yes, penetrated to his marrow—made no mistakes—was staunch, irresistible. Indeed, I think my own Lincolnism was a good deal the result of William's pressure—Gurowski's. I was borne down, the very momentum of the men sweeping all before it. A negative? He would not hear it—no, not a word of it—there was no question! And armed that way, nobody could resist O'Connor." I asked, "A tale might be told of his life among the clerks—his heroisms there." "Yes, a bright glorious tale. Nobody knows so well as I do what wealth of life O'Connor threw into his work at the department." I mentioned a notebook about children, left with me by Mrs. O'Connor, showing that O'Connor was planning to write on the subject. W. thought, "It must have a rare value. O'Connor's love of children, demonstrations towards them, were exquisite." I said, "I am scheming to write something about Walt Whitman and the children." His whole face lighted up, "What a chapter you might make of that! I had an inroad of the children just today—little Harvey (you know little Harvey, my friend, darling?)—and with him half a dozen others. It was a flash of light—a bit out of dawn."

[Begin page 20]We spoke of the marked friendliness of newspaper men to Walt Whitman. I quoted a talk I had with McClure last fall, anent the lecture, McClure saying, "I will do anything for either Walt Whitman or the Colonel." W. asked, "Did he say that? Were they his words?" Adding, "I always felt somehow that I could count on Aleck. And you think the newspaper men generally accept, or credit, me, and the literary fellows not? That has been my own experience. The high-jinks shrink from the issue, but the newspaper boys have no qualms." Miss Porter told me this afternoon that she and Miss Clarke were amusing themselves writing an imaginary conversation between Sidney Lanier and Walt Whitman. W. said, "It ought to amuse them, taken rightly. They might give it a great turn." The two men both patriots, yet with different ideals for America. There the subject at issue. Find the two women strangely and more markedly warm towards Walt. W. says he has sent a postal to Wallace at New York. What of the Rome brothers? "They are both alive—splendid average fellows of their class."

I have been speaking in notes recently about Pan-American Congress. I should have called it Pan-Republic Congress—a different tribunal from the P.A.C. which met in Washington.

Saturday, October 10, 1891

5:55 P.M. W. in his dark room, on the bed—a fire burning in the stove (two lighted logs). Smoke plentiful, yet he did not seem conscious of it. "Is it so? I did not notice." Every window closed. Says he had "felt the chill of out-of-doors." How was he? "Bad—bad." An ill night again to account for it? "I suppose so—I did not sleep at all last night." Continuing, "It was the neuralgia again. It kept me awake the whole night. Yes, Horace, we are entered upon evil days again." Had written a letter to Bucke today and made up a paper for Miss Whitman (Jessie). (These I later took to Post Office.) "I have a letter from Wallace—coming from Brooklyn—written at the Romes'. And as he is fully determined upon the Long Island trip, he can hardly [Begin page 21] be expected here for two or three or four days yet. He speaks of the ride down the Hudson—its wonder—its fortunate good weather. Indeed, he has been mighty lucky in weather. Almost uninterrupted clear pure days—more of 'em maybe than he ever had in his life before." I too had a note from Wallace.

And Bucke writes me, too, under date of the 8th: 8 Oct 1891 My dear Horace All well here. Weather continues wonderful—clear and warm. I have not written to you lately as much as I ought. Being away etc. etc. I have letter from you of 27 ult. and 5 inst. Do not forget me—write from time to time—I will write whenever I have a word to say. The "Star" came—W. seems uncertain but is apt to "get there" in the end. My Montreal venture was a decided success. Mrs. B. & I had a big time—lecture went well—was far more praised than it seemed to me to deserve. It was distinctly wrong of W.S.K. to allude in print to my T. letter—just shows that you can not trust these newspaper men—they are so hungry for anything that will make an item. I have often been loaded down with work but never anything like at present before. Annual report not begun—should go in a week, lectures to students ought to begin at once, no end of meter work which must be done, some pressing family affairs requiring a lot of my time, amusement season just about to open and arrangements to be made for lectures etc. etc., regular asylum work way behind, etc. etc. etc. But I feel well—better than for some years and I shall come out of it all O.K. by and by. I do not hear from W., nor from you much, see that I am kept posted like a good fellow. Love to Anne. Your friend R. M. Bucke W. says as to Kennedy, "It was a violation of confidence, no doubt. Kennedy would unquestionably protect himself behind the anonymity of the paragraph, saying that no names were anyway mentioned. But that would not satisfy me—no, would not. And yet I brought it on myself. I should have known better, though his promises to say nothing about it—to faithfully [Begin page 22] maintain quiet—were warm enough. I had told him we had the letters. I suppose I should not have done even that much. Well, well, Sloane is a queer make-up—baffles me—I am defeated." W. expresses wish to read the manuscripts Bucke left with me—translations—Knortz, Schmidt, Rolleston, Benzon. "They are all in a sense new to me. I should like to mine them—see what I can dig out. And if you will leave them with me for a day or two, I will grapple with the problem." Then again, "They tantalize me, now you tell me of them, for I have never really known any one of them except in snatches."

Sunday, October 11, 1891

Did not see W. Yet found all reputed well there. Has past fortnight been getting up very late—not till towards noon (twelve). So my seeing him on way to Philadelphia is out of question. Nothing definite yet as to Wallace.

Monday, October 12, 1891

5:20 P.M. W. on his bed—had closed shutters—but not asleep. Thermometer down to 63 today—markedly and suddenly cold. W. extended his hand from the bed at once. Spoke rather brightly, yet complained of his condition. "The last two nights have been bad ones—little for sleep—disturbed—the neuralgia pushing me hard. It is a beginning of the end—the disabilities multiplying—life becoming every way more difficult. Longaker has not been over"—since Tuesday—"I was hoping for him. Yet I don't know what he could do. There is nothing, in fact, to be done, but to be cautious—keep the eyes open—lay low. I have no other physical doctrine for a sick man." Had been downstairs last night for an hour, "yet only on Warrie's reminder and urging." They had set the parlor stove up. His own fire now burned brightly—the room comfortable (an unusual case, for if not too warm it is generally too cold). W. said he had received no letter from Wallace today, "Yet I conclude [Begin page 23] all is well." But had received slips, reprint of my third Post piece, from Johnston. "The matter is even better than ever," he averred. "I like it a good deal."

Wallace in Brooklyn. I heard from him today. W. remarking, "He intended going off to West Hills—may be there this minute. No, the railroads do not go to West Hills. What is called West Hills station is a barren desolate spot. It will not cheer him. The place is quite inaccessible. Wallace will find it rather difficult moving about. He should have gone to see Gilchrist. He will find this West Hills excursion harder than is supposed." And again, "I understood from him, too, that Rome would come along. It has been years since we met—many years."

He got up from bed by and by—went toilsomely to chair. "You see what a labor it is getting to be: worse and worse—yes, worse! After a while—well, never mind. But I'm not like to get better!" His mail—a letter to Mrs. Heyde, a postal to Johnston. Had been looking over a copy of Once a Week. But, "I am not much interested." I had been in to see McKay, who disappoints us again. Will not see W. till Saturday or Monday. Says W., "It is enough to turn the stomach: delay, delay, delay, then delay again! Postponements—postponements!" W.'s postal to Johnston was American, with a penny stamp plumped on. He said, "Some of our postal habits or laws are better than theirs in England—in any foreign country: more in the hands of the people. And by the way, Horace, the Post Office in Philadelphia issues a sheet of instructions. Will you see to get me one some day soon? I am curious to see it."

W. asked me about Mr. Hunter. "What do you hear from him? Does Dave hear? Oh! He has been in Philadelphia? And what of him: is he well, and himself? I have been thinking of him today." While he lay on the bed, for some ten minutes he was quiet and I threw out not a word. It was a holy peace—a quiet passing understanding—my memory meanwhile drowsily playing with all the events transpired in this room the past three years. I can say I never elsewhere realized so sudden, so sweet, so entire an abandon to the holiest impulses of reverie.

Tuesday, October 13, 1891

5:30 P.M. Spent half an hour with W., who seemed greatly better. Had just lighted the gas and sat reading. "Longaker has been over and left a good deal of cheer, if nothing else." Yet still thinks or says he is "blue." Is it the echo of the discussion over the payment of the tomb? Fire burning in stove—room pleasant. "Though I slept better last night, 'twas nothing to brag of." Not downstairs again. "I often feel to go down, yet can't bring myself together to do it." Then, "I have a letter from Wallace—written from West Hills. He went there—filled his fill of things thereabout. Says the country is beautiful—only regrets he can't stay, locate, settle there for a while. His letter is very cheery—the best, on the whole, he has written me. The good weather is gone, otherwise he is in good fortune. He tells me about the people he met—how everybody was hospitable—how he went from this thing to that—peering, absorbing, cherishing. It is a long letter—pages of it—and thoroughly in good temper. Now he says he won't be on here till Thursday—that he will go to New York—back there—spend a couple of days there—then come on with Rome—which in a sense will be to end up his pilgrimage." As to Wallace's books, "They are still in the box there, untouched. I am a great dawdler, these days."