Tuesday, July 10, 1888.

Tuesday, July 10, 1888.

[See indexical note p444.4] W. up in his room moving about and closing the blinds when I arrived, 8 P.M. "Day not a bad one for me," he said at once. "The doctors keep dosing me. But what's the good? It's no use trying to put there what is not there—it can't be put in from the outside." Complains of his eyes. Read some today—in the N. A. Review Lincoln volume. Had written nothing—"not even letters to Bucke, Burroughs and Kennedy—to whom I owe my biggest debts." Then: "The main trouble is to know what to say. What can I say? The outlook is too uncertain—I have no knowledge: only hope. I had a card from Kennedy today,—a scrambly

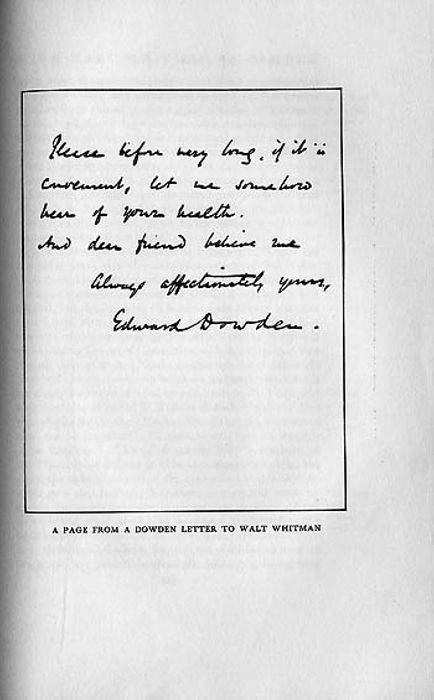

A Page from a Dowden Letter to Walt Whitman

hasty upset characteristic postal. Did you ever notice that Kennedy's writing sort of stands on its head?"

[See indexical note p445.1] Not a word from anybody abroad concerning his sickness. "The work on the book does me good—stimulates me—bears me up. I think I should die if I didn't have the book to do. It is necessary to have an ambition—purpose—something you must absolutely, personally, do. Tell the doctors not to worry—I do not worry. Tell them we are working out a job together and that I have promised you not to die until the work is done. [See indexical note p445.2] That should satisfy even the doctors." I told him there would be no proofs tomorrow. "Good! then I can work on the Hicks."

A Page from a Dowden Letter to Walt Whitman

hasty upset characteristic postal. Did you ever notice that Kennedy's writing sort of stands on its head?"

[See indexical note p445.1] Not a word from anybody abroad concerning his sickness. "The work on the book does me good—stimulates me—bears me up. I think I should die if I didn't have the book to do. It is necessary to have an ambition—purpose—something you must absolutely, personally, do. Tell the doctors not to worry—I do not worry. Tell them we are working out a job together and that I have promised you not to die until the work is done. [See indexical note p445.2] That should satisfy even the doctors." I told him there would be no proofs tomorrow. "Good! then I can work on the Hicks."

W. had received a copy of The Academy. "That's the last thing from abroad—contains a review of the Walter Scott book by Walter Lewin—well written enough, true—but I can't see that it amounts to much: it is scholarly and all that, but light weight. [See indexical note p445.3] The critics are always after the style: style, style, style, damn it style,till your stomach is turned: everything must go for style. Nearly everybody who takes up Leaves of Grass stops with the style, as if that was all there is to it. Nearly everybody—every fellow almost without exception—founders on that rock—goes down hopelessly—a victim of rules, canons, cultures." [See indexical note p445.4] I had said a similar thing to one of W.'s critics in Philadelphia. "And what did he say to that?" asked W. "He said, the canons must not be forgotten." "I thought so: they all stand it off in that way." "That," continued W., "is the bane of the Philadelphia fellows in The American—the style, the dress, the outside manner of the man—they stop with that, never go a step farther. [See indexical note p445.5] Napoleon, as a general, came up against the same class—yes, is a good case in point. When he set to and whacked away at the enemy, the tacticians, the traditionists, the canonites, all cursed him: 'God damn him! he is violating all the laws, the customs, of soldiering we were taught in the schools!' but then the fellow who was getting licked would come on and cry: 'That's true; that's all true; but, God damn him, he's knocking hell out of us anyway!' [See indexical note p446.1] The canon proves that the poet is not a poet—but suppose he is a poet anyway, what can be said for the canons?" W. went all through this with great fire. Paused. Started on again. "And that's the method of the critics everywhere. Why—there was Grant—see how he went about his work, defied the rules, played the game his own way—did all the things the best generals told him he should not do—and won out! Suppose the poet is warned, warned, warned, and wins out? [See indexical note p446.2] Some one in that discussion over the river presented my 'standpoint'—but suppose I have no conscious standpoint? suppose I just write?"

[See indexical note p446.3] W. says he makes his postals to Bucke very specific—"they are all about my bowels, head, symptoms, diet—the professional facts which a doctor knows what to do with." Had not yet put the will into Harned's hands. "I neglect it wickedly." I alluded to a Whitman poem in The Ledger and remarked that a Ledger reference to W. was rare. [See indexical note p446.4] He explained: "That is so and has a good reason. Its editor, McKean, and I don't hitch. That may be my fault. No doubt he's a good man in his place—and his place is important, too—but he is not the sort of man with whom I would have much in common. [See indexical note p446.5] Childs, however, is my kind of a man every inch of him: a generous, devoted friend—I like him, I think he likes me. Childs has made a number of tenders to me which I have declined and some others which I have accepted—all of them delicately done—all of them conceived in the large spirit. McKean has no place—no room—no call for me or my kind." "Did he ever express himself to you?" "No—not to me but to Childs. He told Childs that he regarded me as a poseur whose work was bound to disappear ten years after my death if it lasted that long." [See indexical note p446.6] I broke in: "And you can never disprove him except by dying!" "Good—so it seems. I'll have to leave it to you to disprove McKean!" He spoke of the Herald check—of its several trips—of his final acceptance of it. Referring to Lowell W. said: "I have always been told by the New England fellows close to Lowell that his feeling towards me is one of radical aversion. [See indexical note p447.1] My own feeling towards him is a feeling of indifference: I don't seem impressed by him either way: I have no interest in him—when I look about in my world he is not in sight." "Do you mean by that that you think Lowell is to be of very little permanent consequence in literature?" [See indexical note p447.2] "I suppose I do. I do not mean to say he is momentarily useless: I only mean to say he is not likely to be eternally useful." "That is—as Shakespeare or Emerson or Goethe are likely to be eternally useful?" "You say it for me but you say it all right. That is the idea."