Walt Whitman's Poetry in Periodicals

Although most students of Whitman know that he extensively revised and added new poems to Leaves of Grass from its first appearance in 1855 until his death in 1892, few scholars have studied Whitman's relationship with periodical literature throughout his life. For many years before he published the first edition of Leaves of Grass, Whitman worked as an editor at a series of newspapers. He published a few poems in periodicals before Leaves of Grass appeared in 1855, but he also published poems in periodicals during the years he was revising and expanding his major work. Altogether, he published about 160 poems in 48 periodicals (both magazines and newspapers) from 1838 until his death in 1892.1 And these estimated figures do not include the many poems that were published multiple times or the ones that were published without his permission or even knowledge.

This section of the Walt Whitman Archive is the first gathering of Whitman's poems published in magazines and newspapers during his lifetime. Beginning with Joel Myerson's indispensable Walt Whitman: A Descriptive Bibliography and Leaves of Grass: Comprehensive Reader's Edition, we have located individual poems and established a complete textual record.2 Here users can examine the poems Whitman published in prestigious literary magazines such as the Atlantic Monthly or Harper's Monthly Magazine as well as his largest group of poems published in a periodical, the 34 poems he published in a newspaper in the 1880s, the New York Herald. In this section of the Archive, we provide access to the poems in two ways. The first is through a list of all of the poems collected so far and the second is through a list of all of the periodicals in which Whitman published. Users may locate poems and information by using one or both lists. By clicking on the title of a poem, users can find an image of the poem as it appeared in the original periodical, a transcription, complete publication information, and an editorial note. Users can also click the name of the periodical and bring up a brief historical commentary about the periodical as well as a bibliographic list of any other poems Whitman published in that periodical.

Many of Whitman's poems were published in periodicals that are now rare and, in many cases, difficult to obtain in paper copies. With the cooperation of a variety of libraries and collections, we have been able to collect most of Whitman's published poems and in so doing, have corrected a variety of errors in early bibliographies and have provided page numbers for every citation. Through this electronic archive developed collaboratively by professors, librarians, archivists, e-text specialists, and graduate students, we provide access to these hard-to-find poems, preserve in electronic form the images of pages from the original periodicals or microfilm, and assist scholars and students in understanding another side of Whitman's life as a poet—one who constantly sought publication in the popular periodicals of his day in order to broaden his audience. The process of reading the poems in the periodicals can teach us a great deal about Whitman's publication practices. Indeed, the close examination of the poetry as it originally appeared in the magazines and newspapers themselves raises some important questions. What was Whitman's strategy for publishing the poems in periodicals? How did the periodicals shape the writing and publication of the poems? How did those publications serve the various editions of Leaves of Grass?

The first page of the November 1880 issue of Cope's Tobacco Plant, where "The Dalliance of the Eagles" appeared in print for the first time. Click here to see the poem as it appeared in its original publication.

Scan of Cope's Tobacco Plant.

The first page of the November 1880 issue of Cope's Tobacco Plant, where "The Dalliance of the Eagles" appeared in print for the first time. Click here to see the poem as it appeared in its original publication.

Scan of Cope's Tobacco Plant.

The cover of the June 1871 issue of the Galaxy, where Whitman first published "O Star of France!" Click here to see the poem as it appeared in its original publication.

Scan of the cover of Galaxy from June 1871.

The cover of the June 1871 issue of the Galaxy, where Whitman first published "O Star of France!" Click here to see the poem as it appeared in its original publication.

Scan of the cover of Galaxy from June 1871.

As Emerson guessed in a famous letter following the appearance of Leaves of Grass in 1855, Whitman "must have had a long foreground somewhere."3 That foreground was the periodical press.4 Before 1855, Whitman worked for about a dozen newspapers, four of which he edited, and for all of which he wrote numerous reviews and short articles. During these years, he also published nearly two dozen poems and twenty-two short stories—as well as a novel, Franklin Evans—in a variety of periodicals. As Whitman recognized, periodicals were crucial to the development of an audience for American writers. Certainly his was an increasingly prominent voice in the chorus of writers calling for the development of a national literature. In the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on July 11, 1846, for example, he called for an autonomous "'Home' Literature": "He who desires to see this noble republic independent, not only in name but in fact, of all unwholesome foreign sway, must ever bear in mind the influence of European literature over us—its tolerable amount of good, and its we hope, 'not to be endured' much longer, immense amount of evil. . . . We have not enough confidence in our own judgment; we forget that God has given the American mind powers of analysis and acuteness superior to those possessed by any other nation on earth."5

He continued to develop that theme throughout his career. In an unsigned article, "All about a Mocking-Bird," written for the New-York Saturday Press in 1860, for example, Whitman urged Americans to compose "Our own song, free, joyous, and masterful," exhorting his countrymen to discover American writers: "You, bold American! And ye future two hundred millions of bold Americans, can surely never live, for instance, entirely satisfied and grow to your full stature, on what the importations hither of foreign bards, dead or alive, provide—nor on what is echoing here the letter and spirit of the foreign bards."6 Of course, by 1860 Whitman had a powerful self-interest in promoting his particular version of American poetry. He wished for an audience for his own work, for acknowledgement that he was, as he proclaimed in one of his self-reviews of the first edition of Leaves of Grass, "An American bard at last!"7

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the public demand for American writing grew steadily and the poetry marketplace was flourishing. The editors of newspapers and magazines generally published poetry as well as many reviews of new books of poetry. As one example, The Knickerbocker, established in 1833 for the purpose of promoting American literature, published a variety of poets, including William Cullen Bryant and Lydia Sigourney, who by 1830 was regularly publishing in more than twenty periodicals.8 Although John L. O'Sullivan, coeditor of the United States Magazine and Democratic Review, disliked publishing what he called "magazine verse," he published William Cullen Bryant's "The Battlefield" in the inaugural issue of the magazine in October 1837. He regularly printed poems by James Russell Lowell, William Gilmore Simms, Henry T. Tuckerman, John Greenleaf Whittier, and even some by British poets such as Elizabeth Barrett. Less-well known names were also published; in 1838, O'Sullivan and his co-editor, Samuel D. Langtree, printed a poem by Maria James. A note explains that James, who was born in Wales but raised in central New York, was a domestic servant. In the interest of the democratic principles of the journal, the editors of the magazine proposed to assist in the publication of a volume of her "fugitive poems." And, in due course, her single book of poems, Wales and other Poems, was published in 1839; thereafter, James was included in the popular anthologies of American poetry that began to appear in the 1840s.

This pattern was typical: publication in the pages of periodicals was the primary way in which poets gained names for themselves and—if they were lucky—enough publications to attract the attention of a book publisher. By October 1840, Whitman, certainly one of the less-well-known names, had published ten poems in the Long Island Democrat, where he worked as a compositor and writer. Not as lucky as Maria James, Whitman remained unnoticed. Poems by many other writers like Sigourney, Edgar Allan Poe, Elizabeth Oakes Smith, Alice Cary, and James Russell Lowell were published on the front pages of newspapers and throughout the growing number of literary monthlies like The Knickerbocker, Graham's Magazine, and The American Review (which also published some of Whitman's early, anonymous fiction). In part, such publications were designed to illustrate the fact that conditions in the United States were not inimical to the development of an American literature. In 1842, Daniel Whitaker, editor of The Southern Quarterly Review, exclaimed: "Poetry! Why, America is all poetry. The pages of our Constitution,—the deeds of our patriot sires,—the deliberations of our sages and statesmen,—the civilization and progress of our people,—the wisdom of our laws,—the greatness of our name, are all covered over with the living fire of poetry."9 Following directly from such thinking, Whitman famously proclaimed in his Preface to the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass that "The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem."10 Clearly, it was patriotic to publish poetry; and publication in the periodicals led a fortunate poet to book publication. By my count, in the four year period of 1851-1855 over three hundred new books of American poetry were published. Some of these volumes even sold well: heavily promoted by abolitionists, Frances E.W. Harper's Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects (1854) sold 12,000 copies; and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's Hiawatha (1855), surely the first poetry best seller, sold 43,000 copies in the first year.

In the midst of this burgeoning marketplace, Whitman printed the first edition of Leaves of Grass. Eager to find an audience for his self-published book, Whitman also pressed hard to publish his poems in periodicals. Usually these publications were important to the ongoing revisions and additions that he made to Leaves of Grass. Whitman often published a new poem in a magazine or a newspaper and later incorporated it into Leaves of Grass. Many critics have been content to leave it at that—not interested, perhaps, in what the further implications of the periodical publication might be. In addition to being juxtaposed with stories, news items, and other poems, Whitman's poems were often published with headnotes or introductory statements that users can examine in the images of the periodical pages. The titles and texts of the poems were often quite different from the versions that would be published in the various editions of Leaves of Grass. Beyond those variations, however, are the larger contextual issues that the poems raise about Whitman's strategies for publication.

The poems Whitman published in periodicals before and just after the publication of the third edition of Leaves of Grass in 1860 offer an interesting glimpse into some partial answers to these questions. Whitman published nine new poems in three periodicals between December 1859 and June 1860, a month after the third edition of Leaves of Grass appeared in May. These poems include "A Child's Reminiscence" (later "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking") and "You and Me and To-Day" in the weekly miscellany, The New-York Saturday Press. As Jerome Loving has explained in his biography of Whitman, the Press published a total of seven poems that would be a part of the 1860 edition, including some of the Calamus poems. Few of these have been noted in bibliographies or studied in their original context.11 Whitman also published another poem from the 1860 edition, "Bardic Symbols," (later "As I Ebb'd with the Ocean of Life"), in the Atlantic Monthly. Finally, just after the 1860 edition appeared, he published "The Errand-Bearers," in the New York Times; he eventually revised the poem for inclusion in Drum-Taps (1865). Publishing in these venues, especially the Saturday Press and the Atlantic Monthly, was something of a coup for Whitman—both were powerful literary magazines that published new American writers.

The prepublication of some poems was an integral part of Whitman's marketing strategy for the next edition of Leaves of Grass, which he also promoted by publishing new poems after the volume appeared. Like Henry Clapp—Whitman's loyal friend, fellow Bohemian, and feisty editor of the Saturday Press—Whitman clearly felt that any publicity was good publicity. Self-promotion was hardly unheard of in the 1850s. Robert Bonner, the savvy editor of the New York Ledger, helped make Fanny Fern and the Ledger household names through relentless advertisement in his own newspaper as well as in the columns of others. P.T. Barnum, whom Whitman had interviewed in 1846 for an article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, published the first edition of his Autobiography in 1855, primarily to promote himself and the American Museum. Although Whitman does not seem to have admired Barnum, the poet surely observed that self-promotion through frequent publication was effective. This strategy of self-promotion fit the rough and ready periodical marketplace very well. Whitman was also quite calculated about involving friends and sometimes enemies as unwitting participants in his publication plans. He knew very well that persistence paid off. Certainly his periodical publications demonstrate that he was deeply concerned with reaching the readers of periodicals and using such publications to attract a wider audience.

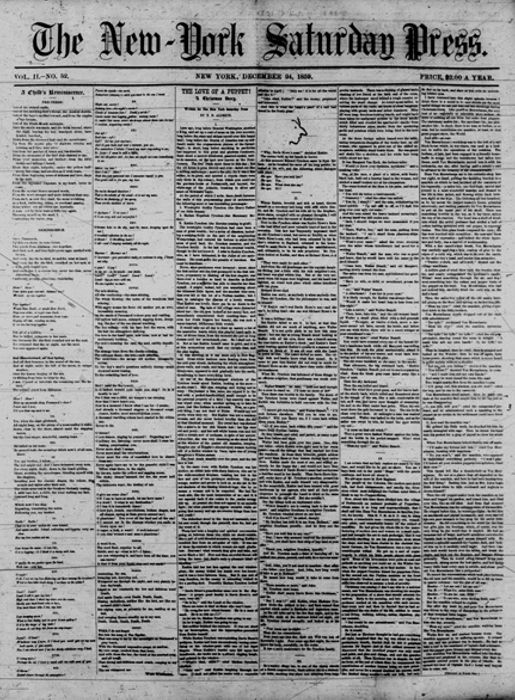

The publication of the poem that became "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking" is a good case in point. Clapp published the poem called "A Child's Reminiscence" on the first page of the Saturday Press on 24 December 1859, along with the following notice at the beginning of his editorial column:

WALT WHITMAN'S POEM.

Our readers may, if they choose, consider as our Christmas or New Year's present to them, the curious warble, by Walt Whitman, of "A Child's Reminiscence," on our First Page. Like the "Leaves of Grass," the purport of this wild and plaintive song, well-enveloped, and eluding definition, is positive and unquestionable, like the effect of music.

The piece will bear reading many times-perhaps, indeed, only comes forth, as from recesses, by many repetitions.12

But that "present" was rejected by at least some readers. A few days later, the poem was attacked in the Cincinnati Daily Commercial. "Curious, it may be," the reviewer commented, "but warble it is not, in any sense of that mellifluous word. It is a shade less heavy and vulgar than the Leaves of Grass, whose unmitigated badness seemed to cap the climax of poetic nuisances. But the present performance has all the emptiness, without half the grossness, of the author's former efforts."13 The Saturday Press, in turn, reprinted the attack and the anonymous response written by Whitman, "All about a Mockingbird," in which he defended his poetry and promoted the forthcoming edition of Leaves of Grass. "We are able to declare that there will also soon crop out the true Leaves of Grass," Whitman announced, "the fuller- grown work of which the former two issues were the inchoates - this forthcoming one, far, very far ahead of them in quality, quantity, and in supple lyric exuberance."14

The first page of the December 24, 1859 New-York Saturday Press. Whitman's "A Child's Reminiscence" is printed in columns one and two. Click here for access to a larger page image and poem transcription.

Scan of the New-York Saturday Press featuring Whitman's "A Child's Reminiscence."

The first page of the December 24, 1859 New-York Saturday Press. Whitman's "A Child's Reminiscence" is printed in columns one and two. Click here for access to a larger page image and poem transcription.

Scan of the New-York Saturday Press featuring Whitman's "A Child's Reminiscence."

Clapp, eager to attract attention and readers to his newspaper, not only published Whitman's poems but also printed parodies of Whitman's poems, as well as promotional advertisements for the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass.15 Throughout the early months of 1860, Clapp was regularly publishing Whitman. "You and Me and To-Day" appeared on January 14, 1860, as one of Clapp's "original" poems, which he printed in nearly every issue of the Press. Poets such as William Dean Howells, Lucy Larcom, Fitz James O'Brien, Thomas Bailey Aldrich, and John Greenleaf Whittier also had poems published in Clapp's "original" columns, which sometimes appeared on the first page of the Press. But the "original" column was not the only place in which Clapp published Whitman. "Of Him I Love Day and Night" was published on January 28, 1860, under the title "Poemet," with a notation at the top of the column "For the Saturday Press." The location of the "Poemet," the upper left hand corner of page 2 of the paper was reserved twice more for Whitman in 1860. A second "Poemet" is "That Shadow My Likeness" (later a Calamus poem), which appeared on February 4, 1860. Finally, on February 11, 1860, Clapp published "Leaves," whose three numbered verses became three distinct poems, two in the Calamus cluster and one in the Efans d'Adam cluster in the 1860 Leaves of Grass.16 "A Child's Reminiscence" and the other poems published in the Saturday Press offer a fascinating lesson in Whitman's—and Clapp's—efforts to promote Whitman's name and book.

Whitman's strategy of promoting Leaves of Grass through periodicals is also illustrated by the publication of "Bardic Symbols," later "As I Ebb'd with the Ocean of Life," in the April 1860 issue of the Atlantic Monthly. So eager was Whitman for publication in the Atlantic Monthly that he allowed its editor, James Russell Lowell, to delete two lines from the fourth stanza of "Bardic Symbols." Ironically, in one of the few positive early reviews of Leaves of Grass, Fanny Fern had specifically commended Whitman's independence and refusal to allow editorial meddling with his work: "Fresh 'Leaves of Grass'! not submitted by the self-reliant author to the fingering of any publisher's critic, to be arranged, re-arranged and disarranged to his circumscribed liking, till they hung limp, tame, spiritless, and scentless."17 Nevertheless, when publication in the Atlantic depended on yielding to the fingering of a critic, Whitman allowed the deletion of the lines, a graphic description of a drowning victim, whose body washed upon a beach. For the 1860 edition, however, Whitman promptly restored the lines and placed the poem as the first in a sequence of untitled poems, in a cluster he called "Leaves of Grass." In yielding to Lowell, Whitman was considerably less picky than Henry David Thoreau, who angrily protested the deletion of lines from the second installment of his essay "Chesuncook" in July 1858 and refused to have anything more to do with the Atlantic while Lowell was editor.18 Indeed Whitman was clearly thrilled to have a poem in the Atlantic, alongside the work of the other poets that Lowell was publishing, including Emerson, Whittier, Longfellow, and Rose Terry (Cooke). That Lowell would publish Whitman also suggests how effective Whitman's campaign had been. Lowell, who had emphatically disliked the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass, was cautiously prepared to try him again.19 The publication of "Bardic Symbols" attracted negative attention (even without the reference to the corpse) which served to again bring Whitman's name before the periodical reading public. In a review of "Bardic Symbols" for the Daily Ohio State Journal, William Dean Howells (who published frequently in Clapp's Saturday Press) emphasized the fact that Whitman was the author of a book of poetry, writing that "Walt Whitman has higher claims upon our consideration than mere magazine contributorship. He is the author of a book of poetry called 'Leaves of Grass,' which whatever else you may think, is wonderful . . . . Now he is in the Atlantic, with a poem more lawless, measureless, rhymeless and inscrutable than ever."20 For the second time in a few months, the publication of Whitman's individual poems attracted attention in periodicals and served to promote his reputation, or at least his notoriety.

Whitman's "Bardic Symbols" (later entitled "As I Ebb'd With the Ocean of Life") appeared for the first time in the April 1860 issue of the Atlantic Monthly. Click here to see the poem as it appeared in its original publication.

Scan of the cover of the Atlantic Monthly from April 1860.

Whitman's "Bardic Symbols" (later entitled "As I Ebb'd With the Ocean of Life") appeared for the first time in the April 1860 issue of the Atlantic Monthly. Click here to see the poem as it appeared in its original publication.

Scan of the cover of the Atlantic Monthly from April 1860.

Soon after the appearance of the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass, which included all the poems published in the Saturday Press and "Bardic Symbols" from the Atlantic, Whitman published "The Errand-Bearers" in the New York Times on June 27. Later entitled "A Broadway Pagaent" in Drum-Taps, it was one of Whitman's occasional poems, written in this instance to commemorate a parade held in conjunction with the first Japanese diplomatic mission to the United States. In January 1860, more than 60 Japanese officials traveled to the U.S. on an American ship, the Powhatan, to meet with President James Buchanan and ratify the U.S.-Japan Treaty of Amity and Commerce. The treaty was signed on May 22, 1860, and a huge parade was held in New York City to celebrate the ratification. Whitman, who attended the parade, immediately wrote "The Errand-Bearers," which was printed in the Times on June 27. Once again, the timing for the publication of a new poem, especially one that celebrated an almost universally approved event, worked well for Whitman. More than one month earlier, on May 19, 1860, a negative review of the 1860 edition had appeared in the Times, castigating Whitman for his style and substance. Describing Whitman's earlier editions of Leaves of Grass as "neither poetry nor prose, but a curious medley, a mixture of quaint utterances and gross indecencies, a remarkable compound of fine thoughts and sentiment of the pot-house," the reviewer called the 1860 edition even "more reckless and vulgar."21 Although it is usually reprinted as a review of Leaves of Grass, the review actually included four books of poetry and was titled "New Publications: The New Poets." The review may have been written by an old friend, William Swinton, the brother of another old friend, John Swinton, the new editor of the New York Times.22 The review included the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass along with books of poetry by Champion Bissell, William H. Holcombe, and Edmund Clarence Stedman. The reviewer found all four of the books lacking, calling Holcombe's Poems "not remarkable in any respect."23 Worth noting, however, is the fact that the reviewer spent nearly two columns on Leaves of Grass and only three short paragraphs on the other volumes. Once again, Whitman managed to command considerable space in a periodical. Not only did the New York Times devote two columns to a review of Leaves of Grass, however negative it might have been, but it also published a long poem of over eighty lines one month later.

The first page of the June 27, 1860 issue of the New-York Times, where "The Errand-Bearers" was first printed. To see the poem as it appeared in its original publication, click here.

Scan of the New York Times in which Whitman's "The Errand-Bearers" appears.

The first page of the June 27, 1860 issue of the New-York Times, where "The Errand-Bearers" was first printed. To see the poem as it appeared in its original publication, click here.

Scan of the New York Times in which Whitman's "The Errand-Bearers" appears.

The poems Whitman published in periodicals from 1859–1860 demonstrate the importance of a close examination of the periodical context for understanding how he negotiated and used magazines and newspapers to construct his image and develop his reputation. In addition, the examples suggest that an archive of the periodical publications introduces a new area of scholarship in Whitman studies, one that has the potential of shedding light on Whitman's publishing practices as well as on the development of the American literary marketplace. Finally, there is another contribution to be made by studying the periodicals. Whitman's career is often figured in the image of a row of eight multi-colored books of various sizes, an image formerly displayed on the Whitman Archive and now on the cover of the recent Norton Critical Edition of Leaves of Grass. Behind that orderly set of volumes and the neat progression it suggests, is a more complicated and diverse set of publications in the periodicals that, as Whitman well knew, were so crucial to the building of an audience and a poet's reputation in nineteenth-century America.

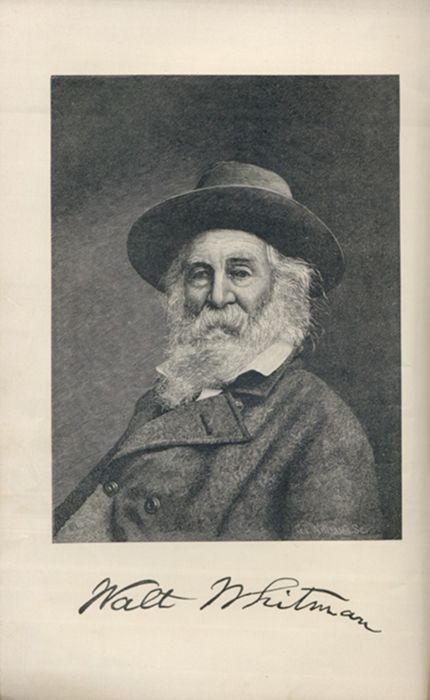

This engraving of Whitman began the March 1891 issue of Lippincott's Magazine. The issue included both prose and poetry by Whitman as well as a piece on the poet by Horace Traubel. Click here to see Whitman's "Old-Age Echoes" as it appeared in its first publication.

Engraving of Whitman from the March 1891 issue of Lippincott's Magazine.

This engraving of Whitman began the March 1891 issue of Lippincott's Magazine. The issue included both prose and poetry by Whitman as well as a piece on the poet by Horace Traubel. Click here to see Whitman's "Old-Age Echoes" as it appeared in its first publication.

Engraving of Whitman from the March 1891 issue of Lippincott's Magazine.

Numerous libraries and collections have been involved in this part of the Archive. We are especially grateful to the staff of the Inter-library Loan Department at Love Library, University of Nebraska, Lincoln. This project has greatly benefited from the invaluable work of several graduate and undergraduate students at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln (Amanda Gailey, Ramon Guerra, Nicholas Krauter, Leslie Ianno, Jason McIntosh, Katherine Ngaruiya, and Janel Simons), as well as Brian Pytlik Zillig, Digital Librarian, Love Library, University of Nebraska, Lincoln; and Brett Barney, Project Manager for the Whitman Archive. Since the fall of 2004, UNL graduate student Elizabeth Lorang has served as the Assistant Editor. Whitman's Periodical Poetry has been supported by grants from the UNL Research Council and the UNL Arts and Humanities Enhancement Fund.

Notes

1. These estimates may change as this project develops. [back]

2. Joel Myerson, Walt Whitman: A Descriptive Bibliography (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1993; Leaves of Grass: Comprehensive Reader's Edition, ed. Harold W. Blodgett and Sculley Bradley (New York: New York University Press, 1965). We have also been helped by new information about first-printings of poems in Jerome Loving, Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999). [back]

3. "To Walter Whitman, Concord, July 21, 1855," The Letters of Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. Ralph L. Rusk and Eleanor M. Tilton (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), 8:446. [back]

4. Important early studies of Whitman and his relationship to periodical literature include Portia Baker, "Walt Whitman's Relations with Some New York Magazines," American Literature 7 (1935), 274-301: Thomas L. Brasher, Whitman as Editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970); Robert Scholnick, "Whitman and the Magazines: Some Documentary Evidence," American Literature 44 (1972), 222-46; Joseph Jay Rubin, The Historic Whitman (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1973); and Shelley Fisher Fishkin, From Fact to Fiction: Journalism and Imaginative Writing in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985). More recent studies that include new insights on Whitman's work in periodicals are Ezra Greenspan, Walt Whitman and the American Reader (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990) and David S. Reynolds, Walt Whitman's America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995). [back]

5. Rpt. in The Collected Writings of Walt Whitman: The Journalism, 1834-1846, ed. Herbert Bergman, Douglas A. Noverr, and Edward J. Recchia (New York: Peter Lang, 1998), 1:463. [back]

6. "All about a Mockingbird," Saturday Press, January 7,1860, 3; rpt. in Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, eds., The Walt Whitman Archive http://www.whitmanarchive.org (accessed December 14, 2006). Except where noted, all subsequent citations to the Archive will be to this address and this access date. [back]

7. [Walt Whitman], "Walt Whitman and His Poems," United States Review 5 (September 1855), 205-12; rpt. in The Walt Whitman Archive. [back]

8. Gordon S. Haight, Mrs. Sigourney: The Sweet Singer of Hartford (New Haven Yale University Press, 1930), 34. For an important account of the poems that Sigourney was publishing in one of those periodicals, see Patricia Okker, "Sarah Josepha Hale, Lydia Sigourney, and the Poetic Tradition in Two Nineteenth-Century Women's Magazines," American Periodicals 3 (1993), 32-42. [back]

9. "American Poetry," Southern Quarterly Review 1 (1842), 496. [back]

10. Whitman, Walt, "Preface," Leaves of Grass (1855); rpt. in The Walt Whitman Archive http://www.whitmanarchive.org/works. [back]

11. Jerome Loving, Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 238. [back]

12. New-York Saturday Press, 24 December 1859, 2. [back]

13. "Walt Whitman's New Poem," Cincinnati Daily Commercial, December 28, 1859, 2; rpt. in The Walt Whitman Archive. [back]

14. "All about a Mocking-Bird," 3. [back]

15. Like many other mid-century periodicals, the Press was always on rocky financial ground. Soon after Clapp's efforts to promote Whitman's new edition of Leaves of Grass, the weekly had to cease publication because of financial problems; it began again five years later, in 1865, when Clapp published "Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog," a story by another iconoclastic writer, Mark Twain. [back]

16. The poems that were published in the New-York Saturday Press and their later appearances are:

- "A Child's Reminiscence," New-York Saturday Press 24 December 1859, 1. "A Word Out of the Sea," Leaves of Grass (1860); "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking," "Sea-Shore Memories" in Passage to India (1871); and in "Sea Drift," Leaves of Grass (1881–1882).

- "You and Me and To-Day," New-York Saturday Press 14 January 1860, 2. "Chants Democratic 7," Leaves of Grass (1860); "With Antecedents," Leaves of Grass (1867).

- "Poemet [Of him I love day and night]," New-York Saturday Press 28 January 1860, 2. "Calamus No. 17," Leaves of Grass (1860); "Of Him I Love Day and Night," Leaves of Grass (1867); slight changes in text in "Passage to India," Leaves of Grass (1871).

- "Poemet [That shadow, my likeness]," New-York Saturday Press 4 February 1860, 2. "Calamus No. 40," Leaves of Grass (1860); "That Shadow My Likeness," Leaves of Grass (1867); slight changes in text in Leaves of Grass (1881–82).

- "Leaves," New-York Saturday Press 11 February 1860, 2. 1. Calamus No. 21," Leaves of Grass (1860); "That Music Always Round Me," Leaves of Grass (1867); in "Whispers of Heavenly Death," Leaves of Grass (1871–72). 2. "Calamus No. 37," Leaves of Grass (1860); "A Leaf for Hand in Hand," Leaves of Grass (1867). 3. "Enfans d'Adam No. 15," Leaves of Grass (1860); "As Adam Early in the Morning," Leaves of Grass (1867).

- "O Captain! My Captain!" New-York Saturday Press, 4 November 1865, 218. Sequel to Drum-Taps (1865); with several revisions in Passage to India (1871, 1876); and finally in "Drum-Taps," Leaves of Grass (1881–82).

17. New York Ledger, May 10, 1856, rpt. in Ruth Hall and Other Writings, ed. Joyce W. Warren (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1986), 275. [back]

18. For a discussion of this incident, see Steven Fink, "Thoreau and His Audience," The Cambridge Companion to Henry David Thoreau, ed. Joel Myerson (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 88. [back]

19. "Norton and Lowell Disagree," Walt Whitman: The Critical Heritage, ed. Milton Hindus (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1971), 30-31. [back]

20. [William Dean Howells], "Bardic Symbols," Daily Ohio State Journal, March 28, 1860, 2; rpt. in The Walt Whitman Archive. [back]

21. [Unsigned], "New Publications: The New Poets," New York Times, May 19, 1860, 9. [back]

22. See C. Carroll Hollis, "Whitman and William Swinton: A Cooperative Friendship," American Literature 30 (1959), 425-49. William Swinton was probably also the author of a review of the 1856 edition of Leaves of Grass in the New York Daily Times, November 13, 1856, 2. [back]

23. "New Publications. The New Poets," 9. The review included Leaves of Grass; The Panic, as Seen From Parnassus, and Other Poems by Champion Bissell; Poems by William H. Holcombe, M.C.; and Poems: Lyric and Idyllic by Edmund Clarence Stedman. [back]