Editing Whitman's Poetry in Periodicals

In a 2004 essay in the Mickle Street Review, Traubel in Paradise, Matt Cohen reflected on the Whitman Archive's creation of a digital edition of Horace Traubel's With Walt Whitman in Camden and the insights such electronic scholarly editing projects can yield. Early in the piece, Cohen considers one of the benefits of the electronic edition, namely the interactivity and intertextuality it allows:

When hyperlinked with resources that are already extant or that will be available in the future manifestations of the Whitman Archive, a rich intertextual picture will be refracted through Traubel's work. The last volume ends, for example, with a transcription and a reproduction of one of Whitman's poetry manuscripts, A Thought of Columbus. This document will eventually appear in the Poetry Manuscripts section of the Whitman Archive . . . . As it happens, Traubel also published this image in the periodical Once A Week in 1892—a very different context from that of With Walt Whitman in Camden; this image will appear in the periodicals section of the Archive.1

At the time, the periodicals section of the Archive to which Cohen refers was still in its early stages, and the possibility of actually linking the documents—the Traubel text and the periodical printing—seemed, at the most optimistic of moments, a distant reality.2 But just three years later, in March 2007, the Archive unveiled Whitman's Poems in Periodicals, a digital documentary edition of Whitman's poems that appeared for the first time in newspapers, magazines, and journals.3 Prior to the work of the Archive, the first publications of Whitman's poems in periodicals—which number approximately 160 poems in nearly 50 different publications—had received limited attention and no significant editorial treatment. The groundbreaking work of Whitman's Poems in Periodicals, under the editorship of Susan Belasco at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, will significantly advance our understanding of Whitman's poetry and textual record, his reception, how he used the periodical press, and how he was viewed in the periodical press. This essay provides an overview of the project, including its methodology, editorial policy, and scholarly apparatus; explores some of the difficulties of the project, from both a technological and editorial standpoint; and considers the value of the project for the Whitman Archive and Whitman scholarship.

Fortunately, while no one has undertaken the collecting and editing of Whitman's poems in periodicals, scholars have been fairly determined, if not always accurate, in their documentation of where Whitman's poems first appeared. As a result, the Archive was able to draw on two indispensable sources in compiling our list of first contributions to newspapers, magazines, and journals. Joel Myerson's Walt Whitman: A Descriptive Bibliography and the Comprehensive Reader's Edition of Leaves of Grass, edited by Harold W. Blodgett and Sculley Bradley, were helpful in this effort. Whitman also kept fairly extensive notes of his periodical contributions, and Traubel provides a valuable record of many poems published in periodicals in the last years of Whitman's life. Working from these sources and an Archive database of all of Whitman's poems recorded as having first appeared in periodical outlets, we located the original publications, or microfilm reproductions as necessary, and carefully noted bibliographic data for each poem.4 This work allowed us to provide and correct page numbers and dates in the existing bibliographic records, such as the appearance of For Queen Victoria's Birthday in the Philadelphia Public Ledger on May 24, 1890 rather than on May 22, 1890. On more than one occasion our work led to more thorough revisions of a poem's recorded publication history. For example, Whitman's poem Twenty Years, listed in Myerson's bibliography as appearing in the British daily newspaper the Pall Mall Gazette sometime during July 1888, and in the Reader's Edition as appearing in the Pall Mall Gazette in July 1888 and then reprinted in the Magazine of Art, was not first published in the Gazette after all. Instead, Twenty Years first appeared in the British Magazine of Art. Confusion over the first publication likely stemmed from the fact that the periodicals shared an editor, M. H. Spielmann, and Spielmann wrote to Whitman requesting a poem. But several passes through the thirty-one issues of the Pall Mall Gazette for July 1888 did not turn up the poem.5 Instead, evidence in Traubel's With Walt Whitman in Camden and poem proofs at the Library of Congress further pointed to the Magazine of Art. The second volume of Traubel includes two letters from Spielmann to Whitman. In the earliest letter, from November 30, 1887, written from the address of the Magazine of Art, Spielmann wrote:

Having added the editorship of this magazine to my duties on the Pall Mall Gazette my thoughts at once turned to you, in the hope that you would let me have a poem for publication in this very widely circulated serial.

Will you have the kindness to inform me if you have such a poem by you—not too long—and unpublished, of course—and, preferably, one which would lend itself to illustration? (232–233)

Eight months later, on July 24, 1888, Whitman received another letter from Spielmann. This time, the editor wrote to confirm publication of the poem: After some months delay I publish in this month's Magazine of Art (which will be next month's in America) your poem of twenty years; and I shall be glad to hear from you if you think the drawing in any way adequately expresses your feelings (104). Along with these letters, a poem proof of Twenty Years at the Library of Congress appears with the writing From the English Magazine of Art.6 Unfortunately, the dating of the publication remains somewhat problematic because of the way the Magazine of Art has been bound and microfilmed.7 Spielmann's letter potentially suggests that the poem appeared in the July issue of the Magazine, but based on the number of pages per issue and the page number on which the poem appears, we believe the poem first appeared in the August issue of the British edition of the Magazine.8

Along with corroborating and adding to the bibliographic record, the Archive's digital edition of Whitman's Poems in Periodicals has also preserved the poems as they appeared in their original publications. In almost every instance, we have created digital scans of the full pages on which Whitman's poems were published. In the case of microfilm reproductions, equipment at the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln enabled the creation of digital scans directly from the microfilm. (Unfortunately, with digital scans derived from microfilm, the quality of the images often suffers from the poor quality of the earlier preservation method. Such a problem forces us to consider the implications of the preservation models we will pass on to future researchers.)9 For a few rare periodicals housed at the Library of Congress, we have had to rely on digital photographs of the original newspaper pages. Whether scanned from the original or microfilm, or photographed from the original, these images of the page or pages on which Whitman's poems appear are available to users of the site. In the near future, Whitman's Poems in Periodicals will also feature cropped views of the poems by themselves, separate from any surrounding text. Locating the poems on large-format newspaper pages is often surprisingly difficult, and the cropped views will address this concern for users most interested in the text of the poems themselves. In addition, these cropped poem views will provide a smaller-size file alternative to the large files necessary to present readable images of the full newspaper pages without stripping them to the starkness of images found at proprietary mass-digitization databases. Currently, the site features only images of the pages on which the poems appeared, but we also plan to add images of covers and tables of contents for the relevant issues. As anyone who has worked with nineteenth-century periodicals knows, these components have been only sporadically bound and microfilmed—and that assessment is a generous one. Knowing we would not be able to provide these materials for all poems, we initially chose to omit them from the site. In the intervening years, however, we have scanned a considerable number of covers and tables of contents. Because so much valuable information can be gleaned from these pieces, we have decided to make available those items we do have and digitize others as possible. Similarly, as the project developed, we began scanning entire issues of the newspapers and magazines in which Whitman's poems appeared. Though most of these scans will not appear on the site, the issues have been electronically preserved for future use in this, or other, projects and research, including more detailed descriptions of the periodical issues in which Whitman's poems appeared.

Along with the page images, we provide encoded transcriptions for every poem, the mark-up of which conforms to the Text Encoding Initiative guidelines.10 As Matt Cohen discusses in his earlier essay, and as many others who work on electronic scholarly editing have commented, the act of transcribing and encoding texts raises important questions about the text being edited and represented. In the case of Whitman's first contributions to periodicals, transcribing and marking-up the texts required that we confront specific details of the texts at both the level of the poem and line as well as at a larger project/theoretical level. There were the inevitable difficulties in ascertaining punctuation and differentiating vowels that one encounters when working from newspapers and microfilm, and which are not unique to electronic editing. The digital scans were often helpful in this instance, allowing us to zoom in, isolate, or otherwise manipulate an image to read more clearly specific characters. Less helpful were later print editions of the poems, as the punctuation in Whitman's periodical printings differs, often radically, from these later bound volumes. From the time Whitman's poems appeared in newspapers and magazines, to their subsequent appearances in book form, Whitman often revised punctuation; further differences in punctuation are likely due to errors in typesetting or editorial changes by hands other than Whitmans. As we conceive of Whitman's Poems in Periodicals as first and foremost a documentary edition, we have not attempted to correct, regularize, or establish authorial intention in the transcription and presentation of these poems. We are less interested in what Whitman must have meant, or where errors or alternate readings were introduced, and are primarily interested in the texts as they were presented in their first publications.

One of the primary, project-level questions raised at the time of transcribing involved how much of the surrounding text to include in the transcriptions and display on the site. If a poem appeared on a page with other material, should we transcribe the entire page, and, if so, then why not the entire issue? In large part, our thinking on this question had to be related to the object of this edition of Whitman's Poems in Periodicals. That is, what did we want to represent in the transcriptions—did we want to privilege the text of the poem, or was there a degree to which we should maintain the integrity of the larger context of the periodical? Based on the belief that most users of the Archive are primarily interested in these periodical printings as they relate to Whitman's poetry, we chose to root our transcriptions in Whitman's poems and extract these from the rest of the periodical text. Though this decision helped constrain the textual unit, it did not fully or perfectly answer the question about what we would be transcribing and encoding. For even if we took a poem as comprising the primary textual unit, there is often surrounding text directly related to the poem, perhaps between the title and body of a given piece. And what then about headlines not written by Whitman that are clearly related to and describe the poems? What about poems that fall within a larger body of text or those that are not clearly delimited from other text by title or similar distinguishing feature? Should we include in our transcriptions editors notes that precede or follow a poem? Many of these decisions had to be made on a case-by-case basis, depending on the individual relationship between the parts. In all instances, however, the central or root text of every transcription is the poem. This editorial choice is represented both in the display of the poems on the site and in the encoding of the poems.

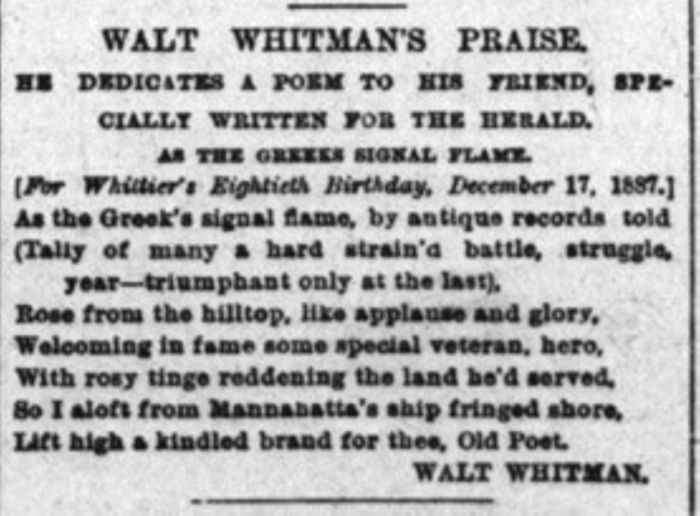

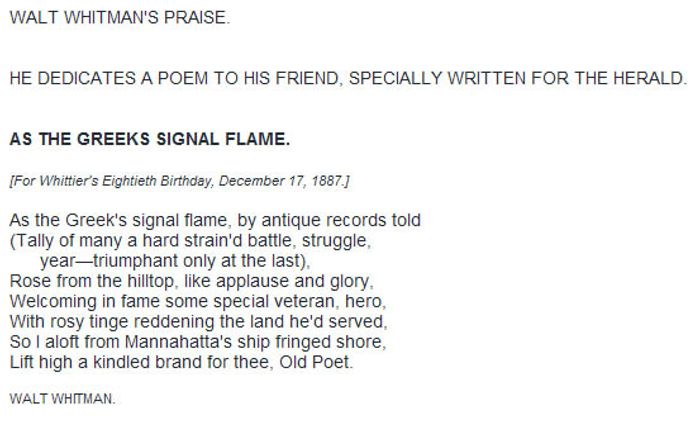

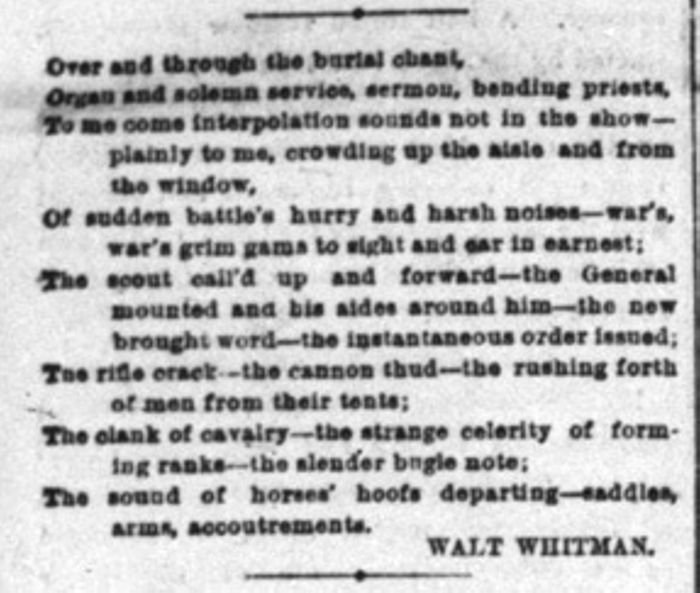

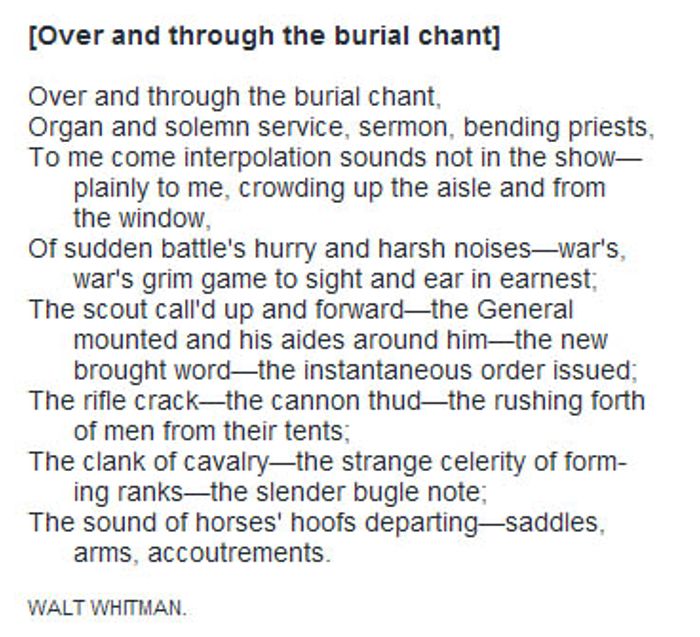

The mark-up and display of two poems, As the Greeks Signal Flame (sic) and [Over and through the burial chant], illustrates these points. For both poems, I have provided a cropped image of the poem as it appeared in its original publication, a section of the poem transcription and mark-up from the Archive's XML file, and an image of how each encoded transcription appears on the Archive.

As the Greeks Signal Flame as it appeared in the New York Herald on December 15, 1887:

image of a microfilm reproduction of Whitman's poem "As the Greeks Signal Flame," as it appeared in the New York Herald

image of a microfilm reproduction of Whitman's poem "As the Greeks Signal Flame," as it appeared in the New York Herald

A section of the transcription and mark-up for As the Greeks Signal Flame:

<lg1 type="poem">

<head type="main-editorial">WALT WHITMAN'S PRAISE.</head>

<head type="sub-editorial">HE DEDICATES A POEM TO HIS FRIEND, SPECIALLY WRITTEN FOR THE HERALD.</head>

<head type="main-authorial">AS THE GREEKS SIGNAL FLAME.</head>

<note type="authorial" place="inline" rend="center-italic">[For Whittier's Eightieth Birthday, <date value="1887-12-17">December 17, 1887</date>.] </note>

<l>As the Greek's signal flame, by antique records told</l>

. . . .

</lg1>

And the poem as it appears on the Archive:

screen-shot of "As the Greeks Signal Flame," as it appears on the Archive

screen-shot of "As the Greeks Signal Flame," as it appears on the Archive

[Over and through the burial chant] as it appeared in the New York Herald on August 12, 1888:

image of a microfilm reproduction of Whitman's poem [Over and through the burial chant], as it appeared in the New York Herald

image of a microfilm reproduction of Whitman's poem [Over and through the burial chant], as it appeared in the New York Herald

A selection of the transcription end mark-up of [Over and through the burial chant]:

<lg1 type="poem">

<head type="main-derived">[Over and through the burial chant]</head>

<l>Over and through the burial chant,</l>

. . . .

</lg1>

The poem as it appears on the Archive:

screen-shot of "[Over and through the burial chant]," as it appears on the Archive

screen-shot of "[Over and through the burial chant]," as it appears on the Archive

The original print contexts of these poems are similar—both were occasional poems on famous Americans published in the New York Herald, and both accompanied other items on Whittier and Sheridan, respectively, on the pages of the paper. At first pass, then, the poems may seem to deserve the same editorial treatment and mark-up. But there are some important differences in the presentation of these poems and the way they relate to surrounding material in the paper that we preserve in the XML encoding and which affects what we display with the text of the poem on the site. In the case of As the Greeks Signal Flame, the poem is the last item in over two columns of material that specifically relates to John Greenleaf Whittier in celebration of his birthday. Whitman's poem, however, is also distinctly separated from the other texts in these columns by horizontal bars. But between the first horizontal bar and the text of Whitman's poem are two editorial titles provided by the Herald's editor and which are specifically related to and describe the poem. They are not, however, titles for the poem in the same way as Whitman's title As the Greeks Signal Flame is. While we have encoded all three titles, or perhaps more accurately two headlines and one title, we have encoded them differently. The titles added by the Herald are marked as heads with the types main-editorial and sub-editorial. The values of the type attribute indicate the editorial intervention and point to someone other than Whitman as the author of these headlines. Whitman's title, on the other hand, is encoded as the main-authorial head for the piece. This encoding distinguishes between the Whitman-authored title, which is subsequently rendered in bold, and the editorial titles, which are part of the text if we posit textual boundaries at the demarcating horizontal bars, but are not Whitman-authored. Similarly, [Over and through the burial chant] appears on an entire page devoted to the funeral and remembrance of General Philip Sheridan. Whitman's poem is the first non-headline text on the page. The inclination may then be to follow the transcription and encoding model used for As the Greeks Signal Flame, which would have us encode all of the headlines preceding the poem, along with the text of the poem. The headlines in this instance, however, function differently than did those with As the Greeks Signal Flame, and they do not have an explicit relationship to the text of Whitman's poem. That is, the stacked headlines refer to a number of items on the page, but none refers specifically to Whitman's poem, and all are separated from the text of the poem by various horizontal bars. In fact, no title appears with the poem, later titled Interpolation Sounds in Good-bye My Fancy. As a result we have encoded here only the text of the poem and have added a head with a value of main-derived for the type attribute. This mark-up allows for a title to be associated with the poem, but as with the main-editorial and sub-editorial values used for As the Greeks Signal Flame, it does not imply Whitman as author. Both of these models privilege the Whitman-authored poem as the primary textual unit, and we have attempted to work with the surrounding texts in meaningful ways. In all cases, the ability to view images of the poems as they appeared in their original publications—something not likely in a print edition—allows readers the opportunity to interpret for themselves if or how to read the surrounding text.

To provide users with additional context for reading Whitman's poems in newspapers, magazines, and journals, we offer an introduction to the study of Whitman and periodicals, available on the index page of this section of the Archive. Susan Belasco's introduction outlines the necessity of editing and preserving these documents, providing access to them, and encouraging scholarship in the field. In addition, Whitman's Poems in Periodicals features short, individual introductions for each of the newspapers, magazines, and journals in which Whitman published. These introductions, or headnotes, help offset our concern about removing the poems from their immediate textual surrounding in our transcriptions by rebuilding some of that context. They provide a history of each periodical, describe Whitman's relationships to a given publication and its editors, and comment on significant textual juxtapositions of Whitman's poems with the rest of an issue. In addition, the headnotes often provide anecdotal information about Whitman and a periodical—for example, the fact that Whitman mailed his mother clippings from Harper's Weekly while he was in Washington, D.C. Such information deepens our understanding of both Whitman and the publications. Following this narrative information, each headnote lists all of Whitman's poems to first appear in that periodical and their subsequent publication histories. Finally, each headnote includes a bibliography of sources consulted and in which users will find additional information. Users can access these headnotes from the main periodicals page, and transcription pages also provide a link to the relevant periodical introduction.

Along with the project introduction and headnotes for each periodical, individual poems will eventually include editorial notes, as appropriate. The New York Herald poems, which already include editorial notes, provide a model for this part of the project. For these pieces, we have provided notes to explain people, places, and events mentioned in the poems. In addition, we have commented on significant textual variants between the periodical printings and the deathbed edition of Leaves of Grass. We have also provided notes on the public reception of several of the poems, as well as further items of interest related to the rest of the New York Herald, Whitman's correspondence, and his biography. For the remaining periodicals, we will begin by providing notes on all people, places, and events and then return to the poems to provide additional contextual notes and indicate textual variants. In composing these notes we will look to titles in the Collected Writings of Walt Whitman, to Traubel's With Walt Whitman in Camden, to existing critical studies on individual poems and periodicals, and to detailed exploration of the periodical texts. In time, as the Archive digitizes Whitman's correspondence and select critical texts, we will be able to provide links from our notes to these other sources. Editorial notes for the Herald poems already link to several volumes of With Walt Whitman in Camden (presented under the Disciples section of the Archive), as Traubel began this record just prior to Whitman's official contract with the newspaper as an outlet for his poetry.

To return to Matt Cohen's original point, this interactivity of texts is not something one can achieve in the print environment. Thus, we both offer much of the editorial apparatus one would find in a print edition and take advantage of the digital environment, to the benefit of the project and its users. One such advantage is the ability to continue to add materials and revise as necessary. Complete page-by-page descriptions of the periodical issues in which Whitman's poems appear are one possible future addition to the project. Clearly, postponing the release of the project until such descriptions can be completed would mean not making the material live for several more years. But in the digital environment, we can update these records as time and labor allow, and users can begin exploring the wealth of existing materials. At the time of writing, the Archive makes page images and transcriptions available for 143, and transcriptions available for 155, of Whitman's approximately 160 poems that appeared for the first time in periodicals.11 Gathering the remaining poems, from some of the rarest periodicals in which Whitman published, will be difficult. But our efforts to track down these texts and present them on the site are ongoing, and we hope to attract the attention of scholars and collectors who might help us by providing access to these items. The Archive's goal in offering this digital edition is to present a significant body of work that has never been gathered, edited, and analyzed nor made widely available to the public. The rarer items are therefore a crucial part of the project.

Names of periodicals and dates of publication alone tell us very little about the first printings of Whitman's poems. With this limited information, we cannot ascertain textual variants; we cannot imagine the poems in their original contexts, juxtaposed with other items of real cultural significance; we cannot place a poem's appearance in a given periodical within the larger meaning and cultural work of the newspaper or magazine. In short, bibliographic records alone do very little except offer a small glance at the range of publications in which Whitman appeared. What Whitman's Poems in Periodicals hopes to illuminate is the important work waiting to be done on Whitman's relationship to the periodical press and the reading of his poems in their immediate print and cultural context. The Archive's digital documentary edition of these poems serves as an entry point into the field for Whitman scholars, as well as scholars of periodical literature. We expect that the page images, transcriptions, and contextual information will prompt new explorations of Whitman's poetry and nineteenth-century periodicals, without advocating what those explorations might be. Undoubtedly, periodicals played a profound role in Whitman's career, and he certainly had an impact on the publication of literature in periodicals. The value for Whitman scholarship is a more complete account of Whitman's textual record, a more integrated understanding of how we place these poems in the Whitman corpus, and a further valuation of these poems based on their cultural function.

Notes

1. Matt Cohen, Traubel in Paradise, Mickle Street Review 16 (2004). [back]

2. The text of Whitman's poem appeared in print for the first time in the July 2, 1892 issue of Once A Week. In the following week's issue of July 9, 1892, the manuscript facsimile was printed, and two weeks later, on July 16, 1892, Traubel's article on Whitman's composition of the poem appeared in the newspaper. [back]

3. Whitman's Poems in Periodicals is available at whitmanarchive.org/published/periodical/index.html [back]

4. The interlibrary loan department at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln played a crucial role in this part of the project, and without the help of ILL staff, our edition would not be nearly so complete. [back]

5. The incomplete publication record that indicated a publication date of only July 1888 for a periodical that was published daily was immediately suspect. The lack of a more specific date indicated that scholars had likely not gone back to the periodical to look for the original publication and that the July 1888 date was one simply passed on in Whitman scholarship without verification. [back]

6. Traubel, Horace. With Walt Whitman in Camden. Vol 4. Ed. Sculley Bradley. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1953. A second poem proof of Twenty Years at the Library of Congress includes the date June 14, 1888 written in Whitman's hand at the bottom of the page. [back]

7. The reel of microfilm we obtained with the British edition of the magazine lacks features that make it easy to discern where one issue ends and another begins, as does the bound volume of the American edition. Each issue of the Magazine of Art apparently began with a monthly Chronicle of Art, which detailed upcoming art events. These pages were numbered with Roman numerals and when the issues were later microfilmed, all of the monthly chronicles were placed at the beginning of the annual volume; in the bound volume, the chronicles come at the end of the volume. In addition, no covers or tables of contents survive, and the pages are numbered consecutively across issues. The remaining first pages of each issue do not contain other distinguishing features. [back]

8. After failing to identify page breaks by other methods, we resorted to arithmetic calculation to help determine the issue breaks. The issues from October 1887 to September 1888 span 430 pages (not counting the Chronicle of Art sections); dividing 430 by twelve indicated that each issue should come in at roughly 36 pages. We then looked at the volume at 36-page intervals, and the issues do appear to break at these points. We checked this pattern on other volumes, and it seems to hold true for them as well. [back]

9. For more on the implications of preservation methods for future researchers, see Margaret Beetham, Towards a Theory of the Periodical as a Publishing Genre, in Investigating Victorian Journalism, eds. Laurel Brake, Aled Jones, and Lionel Madden (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1990), 19-32. [back]

10. Sperberg-McQueen, C. M., and Burnard, L., eds. TEI P4: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange. Text Encoding Initiative Consortium (XML Version: Oxford, Providence, Charlottesville, Bergen). [back]

11. At present, we have not been able to obtain digital scans of the ten poems that first appeared in the Long-Island Democrat from 1839-1841. We have, however, completed transcriptions from photocopies of microfilm of the original. [back]