Venereal excesses occasion the most loathsome, and horrible, and calamitous

diseases that human nature is capable of suffering....By far the worst form

of venereal indulgence is self-pollution; or, what is called "Onanism"....I

am confident that I speak within bounds, when I say, that seven out of every

ten boys in this country at the age of twelve, are, at least, acquainted

with this debasing practice: and I say, again; the extent to which it prevails

in our public schools and colleges, is shocking, beyond measure! I have known

boys to leave some of these institutions at the age of twelve and thirteen,

almost entirely ruined in health and constitution, by this destructive practice;

and they have assured me, that, to their certain knowledge, almost every

boy in the school practiced the filthy vice; and many of them went to the

still more loathsome and criminal extent of an unnatural commerce with each

other!

-Sylvester Graham, "A Lecture to Young Men" (1834)

Sylvester Graham's message here was directed toward young

men like Walt Whitman, teenagers in the early 1830s.

Whitman, in fact, attended the infamous "public

schools" (in Brooklyn between 1825 and 1830) that Graham discusses in the

above passage. Sylvester Graham's condemnation of "venereal" or sexual

excesses--especially in the what he sees as the related forms of masturbation

(referred to as "Onanism") and homosexuality--is one of the first and most

prominent examples of how popular health reformers and others were attempting

to limit and control male sexuality during this period. For Graham (yep,

the Graham cracker is named after him) men were fragile beings whose systems

reacted adversely to any physical stimulation.

Click on the title

page of his "Lecture to Young Men" (on the right) to find out more details

about Graham's representations of men and their bodies.

Whitman, in fact, attended the infamous "public

schools" (in Brooklyn between 1825 and 1830) that Graham discusses in the

above passage. Sylvester Graham's condemnation of "venereal" or sexual

excesses--especially in the what he sees as the related forms of masturbation

(referred to as "Onanism") and homosexuality--is one of the first and most

prominent examples of how popular health reformers and others were attempting

to limit and control male sexuality during this period. For Graham (yep,

the Graham cracker is named after him) men were fragile beings whose systems

reacted adversely to any physical stimulation.

Click on the title

page of his "Lecture to Young Men" (on the right) to find out more details

about Graham's representations of men and their bodies.

Graham himself was not a doctor, but as the 19th century

progressed many well-respected doctors began to adopt similar views about

the male body and the dangers of too much sexual activity. Articles

against masturbation, for example, began appearing in such prominent medical

journals as the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal and The American

Annals of Education. As Whitman grew older, he cultivated

acquaintances with several of the doctors who were writing on male sexuality,

such as Edward H. Dixon.

Click on the

title page of one of Dixon's pamphlets (on the left), "The Organic Law of

the Sexes: Positive and Negative Electricity and the Abnormal Conditions

that Impair Virility," to find out more details about his relationship to

Whitman.

Graham himself was not a doctor, but as the 19th century

progressed many well-respected doctors began to adopt similar views about

the male body and the dangers of too much sexual activity. Articles

against masturbation, for example, began appearing in such prominent medical

journals as the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal and The American

Annals of Education. As Whitman grew older, he cultivated

acquaintances with several of the doctors who were writing on male sexuality,

such as Edward H. Dixon.

Click on the

title page of one of Dixon's pamphlets (on the left), "The Organic Law of

the Sexes: Positive and Negative Electricity and the Abnormal Conditions

that Impair Virility," to find out more details about his relationship to

Whitman.

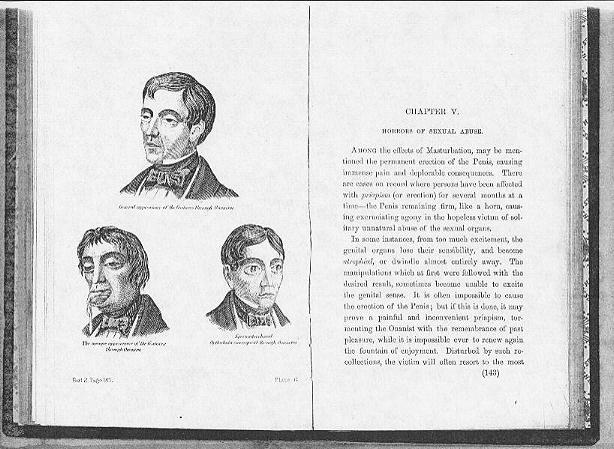

Dixon and other doctors, such as Samuel B. Woodward,

R.T. Trall, and Seth Pancoast, detailed the drastic consequences of indulging

in masturbation or other sexual behavior. On one level, these doctors

showed, in very explicit terms, the physical effects of these sexual "diseases"

on the male body. In his book, "Hints for the Young in Relation to

Body and Mind," Woodward writes of boys who engage in the "secret vice":

"The individual becomes feeble, is unable to labor with accustomed vigor,

or to apply his mind to study; his step is tardy and week, his is dull,

irresolute, engages in his sports with less energy than usual, and avoids

social intercourse."

In more dramatic fashion in his book, "Home-Treatment

for Sexual Abuses: A Practical Treatise," Trall claims that "self-pollution"

could produce a "fatal result" and he calls the man who he believes dies

from masturbation a "victim of self-murder." In his book, "Boyhood's

Perils and Manhood's Curse: An Earnest Appeal to the Young of America,"

Pancoast even goes so far as to include illustrations of young men

who have been debilitated by masturbation:

The caption below the top illustration reads: "General appearance of the

features through Onanism." Below the lower left illustration: "The meagre

appearance of the features through Onanism." Below the lower right

illustration: "Spermatorrhacal Opthalmia consequent through Onanism."

These illustrations precede "Chapter V"--which is entitled, "Horrors of Sexual

Abuse."

Significantly, though, these doctors do not show the

effects of these "sexual abuses" simply upon the male body itself; they also

began to connect these seemingly personal problems with the political problems

of a nation at large. For some, like Dr. Pancoast, men's inability

to control their own desires threatened the stability of the country as a

whole. He writes:

The practice of Masturbation is, at once, a violation of the Law of

Nature, or the Law of Life, in the face of common sense and reason. It

is not only a sin against the body, but against the mind--against

that sublime and etherial principle which springs of Heaven itself.

By consequence, it is punished by the severest of afflictions. As

the great physician, Reveille-Parise of France, has well and most

truthfully remarked--'Neither the plague, nor war, nor small-pox, nor similar

diseases, have produced results so disastrous to humanity, as the pernicious

habit of Masturbation: it is they destroying element of civilized societies

which is constantly in action, and gradually undermines the health of 'nations.'

Pancoast illustrates these national consequences with a portrait of "The

Onanists and their Child":

One of the most interesting details of this illustration is the clothing

of each member of the family. The clothing of the father seems to

indicate that he is a member of an aristocratic gentility, but the clothing

of the mother and child appear to be or a lower class. We might ask

the question: what is the connection Pancoast is making between excessive

sexual activity and social standing in the nation?

Woodward

and Trall expressed similar anxieties about the state of a country in which

the men indulge in "deviant" sexual behavior. As men began to spend

more time away from the home, health reformers and doctors worried that,

in addition to masturbation, men might also be carrying on sexual relationships

with each other. The emerging "self-made man" in early 19th-century

America was only supposed to be interacting with other men in official

capacities in the business world, but some writers wondered whether they

might also be tempted to indulge in, as Graham puts it, an "unnatural commerce"

with each other. The result of that "unnatural commerce" threatened,

in these writers' minds, the very foundations of the nation. Despite

these anxieties, men, nevertheless, continued to socialize with each

other--albeit in place where male bonding was "safe." The daguerreotype

on the right shows three members of a fraternal organization in 1850.

Around this time fraternal organizations, such as the Masons, began

to see a dramatic increase in membership. Sociologist Michael Kimmel

writes, "With rituals heavily laden with religious symbolism and myth,

fraternalists were devoted to a form of manly nurture. Lodges were

the only place where men would wear aprons or dresses."

Woodward

and Trall expressed similar anxieties about the state of a country in which

the men indulge in "deviant" sexual behavior. As men began to spend

more time away from the home, health reformers and doctors worried that,

in addition to masturbation, men might also be carrying on sexual relationships

with each other. The emerging "self-made man" in early 19th-century

America was only supposed to be interacting with other men in official

capacities in the business world, but some writers wondered whether they

might also be tempted to indulge in, as Graham puts it, an "unnatural commerce"

with each other. The result of that "unnatural commerce" threatened,

in these writers' minds, the very foundations of the nation. Despite

these anxieties, men, nevertheless, continued to socialize with each

other--albeit in place where male bonding was "safe." The daguerreotype

on the right shows three members of a fraternal organization in 1850.

Around this time fraternal organizations, such as the Masons, began

to see a dramatic increase in membership. Sociologist Michael Kimmel

writes, "With rituals heavily laden with religious symbolism and myth,

fraternalists were devoted to a form of manly nurture. Lodges were

the only place where men would wear aprons or dresses."

To learn more about

the views of Woodward, Trall, and Pancoast and the medical representations

of men during this period, click on the title pages of the their books

below:

Woodward

Trall

Pancoast

What blurt is this about virtue and vice?

Evil propels me and reform of evil propels me, I stand indifferent,

My gait is no fault-finder's or rejecter's gait,

I moisten the roots of all that has grown.

-Whitman, "Song of Myself" (464-468)

I do not press my fingers across my mouth,

I keep as delicate around the bowels as around the head and

hear,

Copulation is no more rank to me than death is.

-Whitman, "Song of Myself" (519-521)

(Know once for all, avow'd on purpose, wherever are men like me, are

our lusty lurking masculine poems)

-Whitman, "Spontaneous Me" (11)

We can read much of Whitman's poetry as a sometimes

direct, sometimes indirect response to the health reformers, doctors and

others who were attempting to limit and control male sexuality. Whitman,

in many cases, uses the identical vocabulary as the writers we have been

looking at. Words such as "blood," "health," "energy," "virtue," "vice,"

"appetites," "copulation," "lust," "sex," "genitals," "semen," "seminal,"

"disease'd," and "venereal" are, as we have seen, part of the medical discourse

of his time. Does Whitman use these same terms

in a different way, however?. Notice how he plays with some of the

terms in the following verses, sections 1, 22 and 24 of "Song of Myself."

As you are reading these sections, also notice how Whitman is representing

the male body. When Whitman claims in section 24 his own body is

"turbulent, fleshy, sensual, eating, drinking and breeding," how does that

compare with representations we have seen of the male body as a fragile,

closed system?

"1": I celebrate myself and sing myself...

"22": You sea! I resign myself to you also--I guess

what you mean...

"24": Walt Whitman, a kosmos, of Manhattan the

son...

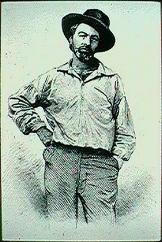

Compare also the daguerreotype (an early type of photograph--shown at the

right) that Whitman himself placed on the first edition of Leaves of

Grass, the edition which contained his first version of "Song of Myself."

How does it compare to the illustrations and textual representations

of the male body in the pamphlets and books of the health reformers and doctors

of his time? After all of the sexual activity he describes in the

passages you have just read, does his posture surprise you?

In "Song of Myself" Whitman refers continually

to times when he is touching himself, when other men or women are touching

him, when nature (the "amorous wet" of the "sea" or the "soft-tickling genitals"

of the "wind") is touching him. You might ask yourself, does

any type of sexual activity bother him? Or is he is completely comfortable

and self-confident in his representation of his own body? Read the

following verses from section 28 of "Song of Myself" and from the poem,

"Spontaneous Me" from a later cluster of poems Whitman wrote, "Children of

Adam." How do they compare with the other verses you have read

and to the texts of the health reformers and doctors of his time?

"28": Is this then a touch, quivering me to a new

identity...

"Spontaneous Me"

Finally, read the following poems from the

"Calamus" cluster, a set of poems, like "Children of Adam," that was added

to Leaves of Grass in a later edition. Physical love between

men was seen by Graham and others as "more loathsome" than masturbation;

he even refers to it as "criminal." How is Whitman representing

homosexuality in the following poems? Furthermore, how does his

representation of homosexuality fit into his idea of "democracy" and the

American nation? We have seen how the health reformers and doctors

believed that masturbation and other "excessive" sexual activity threatened

"civilized societies." For Whitman, what place does sexual

activity--particularly homosexuality--have in the nation?

"In Paths Untrodden"

"For You O Democracy"

"When I Heard at the Close of Day"

"I Hear It Was Charged Against Me"

"We Two Boys Clinging Together"

"A Glimpse"

Return to Representations

Return to Main Page