| As a painter, Thomas Eakins had a relationship with Walt Whitman unlike

any other. Born in Philadelphia in 1844, Eakins did not meet Whitman until

the latter half of the 1880's, but "the two men had a deep respect for

each other" (Goodrich 122). In his old age, Whitman had relocated to Camden,

New Jersey, right across the Delaware and very close to Philadelphia. Eakins

"went into the wilds of New Jersey where he found. . . Walt Whitman, in

a self-chosen exile of his own. Expelled from the bourgeois world, or so

the legend ran, Whitman and Eakins together built the metaphysics for a

distinctly American realism -- the poet's ecstatic and high-hearted, the

painter's murky and inward-turning" (Gopkin 78). The two men shared not

only a friendship and mutual respect, but an artistic vision of American

democracy grounded in realism.

Philadelphia-Camden Friendship: Celebrating America

The two artists had similar ideas of America and art. "Whitman disliked European manners and conventions, and he was passionately devoted to America and to a celebration of the democratic ideal. . . The chief similarity between Eakins and Whitman was their self-sufficient confidence, which allowed them to disregard the conventions of their time. Eakins, like Whitman, insisted on making art in a way that seemed most appropriate and truthful, without giving in to popular or critical opinion" (Homer 217). They were individualists who did not waver in the face of criticism. Both men were artistically rejected in their lives -- though as Whitman aged he gained more popularity. Eakins was scrutinized by the bourgeois Philadelphia society. He paid a high price for his fascination with the nude body. Whitman also had a fascination with the body, but because of the nature of poetry -- words -- was less explicit than Eakins, who painted the body. "Both were democrats, despising forms and conventions which hid the essential human being" (Goodrich 122). The tendency to celebrate the human body was prevalent in both Whitman and Eakins' work. A major difference must be brought to light, though: "Eakins concentrated on the individual; Whitman, on humanity and the cosmos" (Homer 219). In spite of this idea, Eakins was still profoundly indebted to the poet. When Weda Cook (who wrote music to O Captain, My Captain!) was posing for Eakins, "the artist talked much to her about Whitman and would sometimes quote his verses" (Goodrich 122). Not only was Eakins fond of Whitman's poems, but "it was the concrete, realistic side of the poet, his observation, and his feeling for the body, that appealed most to the painter, who used to say: 'Whitman never makes a mistake'" (Goodrich 122). It is this admiration that Eakins can be classified as a Whitmanian painter. Walt

Whitman by Thomas Eakins

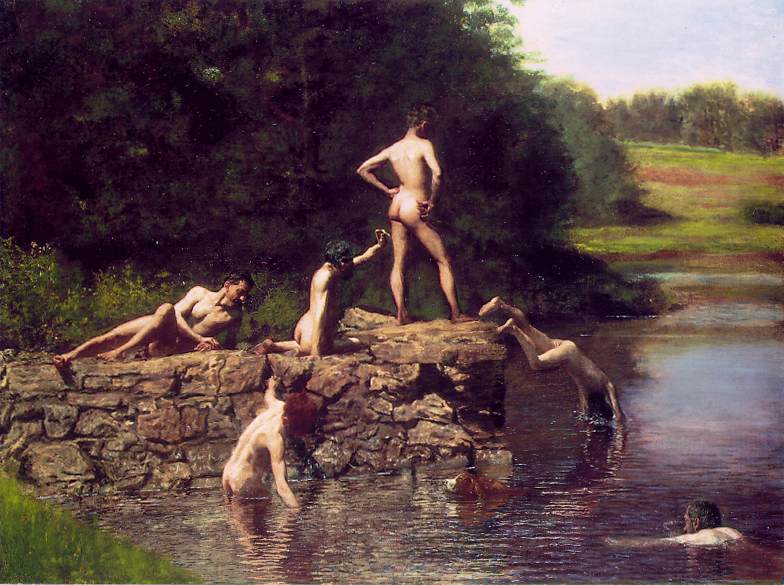

The Swimming Hole and "Song of Myself"

Twenty-eight young men and all so friendly; Twenty-eight years of womanly life and all so lonesome. She owns the fine house by the rise of the bank,

Which of the young men does she like the best?

Where are you off to, lady? for I see you,

Dancing and laughing along the beach came the twenty-ninth

bather,

An unseen hand also pass'd over their bodies,

The young men float on their backs, their white

bellies bulge to the sun, they do not ask who seizes fast to them,

In Swimming: Thomas Eakins, the Twenty-ninth Bather, Elizabeth Johns suggests that the above poem is applicable to the lives of the two men. "Here, Whitman as the woman who is both poet and character in the poem brings the young men into full sexual experience, but, in the self-centeredness of immaturity, they do not recognize her agency" (Johns 77). The poem again acts as an influence on Eakins: "In Whitman's poem are the two worlds in Eakins' picture: one inhabited by high-spirited young men -- the subjects of Swimming -- the other by an observing presence that rejoices in their beauty and loves them with a tenderness and passion of which they are oblivious" (Johns 77-8). Thomas Eakins is a Whitmanian painter; he was inspired and influenced by the the great poet Walt Whitman. Eakins had the unique opportunity to befriend the poet -- he therefore is influenced by Whitman as a poet and as a person. Their friendly personal relationship is evidence of this, as is The Swimming Hole. As realists, Eakins and Whitman again are similar -- both want to depict the actuality of America. |