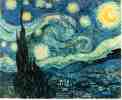

| "Van Gogh said very little about the Starry Night, providing

neither a minimal inventory nor any explanation as to why he painted it

when he did. Later commentators have concentrated on its complex symbolic

imagery" (Pickvance 103). Vincent Van Gogh's most famous work, Starry

Night, has been a question mark to scholars since 1889, the year it

was painted. Art historians have speculated about the painting's origin

over the years; theories include: a rewriting of the Bible (Genesis or

Revelations), a result of his deteriorating mental state (Van Gogh was

in an asylum when he painted it), a result of Emile Zola's writings, and,

alas, a visual interpretation of Walt Whitman's poetry. It is this last

theory that I am interested in for the purposes of this site.

Van Gogh on Whitman

It is admittedly a stretch to label Vincent Van Gogh a Whitmanian painter,

but there is irrefutable evidence that Walt Whitman's poetry influenced

Van Gogh's most famous painting. But Whitman's influence is clear from

Van Gogh's mindset in late-1888 to mid-1889, when he painted Starry

Night. The fact that Van Gogh not only admired Whitman but was avidly

reading him during this time surfaces in a letter to his younger sister

Wilhelmina:

Have you read the American poems by Whitman? [his italics]

I am sure Theo has them, and I strongly advise you to read them, because

to begin with they are really fine, and the English speak about them a

good deal. He sees in the future, and even in the present, a world of healthy,

carnal love, strong and frank� of friendship� of work� under the great

starlit vault of heaven a something which after all one can only call God�

and eternity in its place above this world. At first it makes you smile,

it is all so candid and pure; but it sets you thinking for the same reason.

The "Prayer of Columbus" is very beautiful (Van Gogh 445).

This passage illustrates that, without doubt, Van Gogh was reading Whitman

around the time he painted Starry Night. This letter was written

around September or October of 1888, and Starry Night was painted

in June 1889. To further link Whitman to Van Gogh's painting, it is important

to note the letter Van Gogh wrote to Wilhelmina before the above section

on Whitman. This letter was written around 8 September 1888. "At present

I absolutely want to paint a starry sky. It often seems to me that the

night is still more richly colored than the day, having hues of the most

intense violets, blues and greens" (Van Gogh 443). To clarify, the chronology

is as follows: Van Gogh tells his sister that he wants to "paint a starry

sky," then he recommends that she read "the American poems by Whitman."

Whitman and the starry sky were both in his head before they synthesized

into Starry Night. Though he never said much about the painting,

is there a better explanation than what he says in the above letter?:

"Under the great starlit vault of heaven a something which after all one

can only call God" (Van Gogh 445).

The fact that Van Gogh entitled the painting Starry Night is

another allusion to Whitman, since Whitman's From Noon to Starry

Night was first published in France in 1888 (Schwind 4). "That Whitman

is central to Starry Night is suggested not only by the reference

of the title, but by Van Gogh's description of the work in his letters.

Starry Night, Van Gogh told his brother and [Emile] Bernard, was

his only �poetic' or imaginative subject; it is a version of the portrait

of �the poet in a starry night' that Van Gogh first mentioned to Bernard

in late 1888" (Schwind 4). Van Gogh, while thinking about a painting of

a starry sky, was reading and admiring the works of Walt Whitman.

Starry Night inspired by "Song of Myself"

Whitman's "Song of Myself," particularly section 21, is the work that

inspired Van Gogh:

I am he that walks with the tender and growing night,

I call to the earth and sea half-held by the night.

Press close bare-bosom'd night--press close magnetic nourishing

night!

Night of south winds--night of the large few stars!

Still nodding night--mad naked summer night.

Smile O voluptuous cool-breath'd earth!

Earth of the slumbering and liquid trees!

Earth of departed sunset--earth of the mountains misty-topt!

Earth of the vitreous pour of the full moon just tinged

with blue!

Earth of shine and dark mottling the tide of the river!

Earth of the limpid gray of clouds brighter and clearer

for my sake!

Far-swooping elbow'd earth--rich apple-blossom'd earth!

Smile, for your lover comes.

Prodigal, you have given me love--therefore I to you give

love!

O unspeakable passionate love (Whitman 208).

This theory focuses on the yin-yang type sexual relationship explored in

the above Whitman passage and further in Van Gogh's painting. Lewis Layman

says that: "Whitman renders his vision of a harmonious union in which

earth and sky fuse together and yet retain their distinctness" (Layman

106). Whitman gives a masculine personification in the line "I am he that

walks with the tender and growing night." Opposite this is the feminine

earth, which receives "the vitreous pour of the full moon," and brings

forth apple-blossoms. The comparison seems like a masculine night/sky power

and a feminine earth power, but Whitman jumbles the distinction with the

line, "Press close bare-bosom'd night." Layman suggests that the harmony

exists in "An interplay between two androgynous forces" (Layman 106). In

Starry Night, we see this idea visually: "The unity is similar to

Whitman's vision of the sky and the earth as distinct from each other,

yet in harmony" (Layman 106). The sexual ambiguity exists in the painting

as well. The hills' shape echoes the "bare-bosom'd night," and the large

and intruding cypress tree conjures up an image of a phallus. The crescent

moon is interesting--it is at first glance a moon, but actually resembles

a combination of a moon and sun. The moon, with a striking parallel to

the Chinese yin-yang symbol, is therefore the embodiment of harmony.

The movement of Van Gogh's paint brush also echoes Whitman's lines.

Van Gogh's sky is in a state of movement and "press[es] close" to the earth.

"The circular movement is a manifestation of a vital 'magnetic' force which

seems to draw the tree and steeple upward. The night is 'nourishing' in

the sense that it is fertile to the earth" (Layman 107).

The attraction between the earth and the sky is just as prominent in

Starry Night as in "Song of Myself." Equally pertinent to this discussion

is Van Gogh's 11 stars, each thoroughly emphasized in the painting. "He

expresses the Whitmanian sentiment that each star, like each blade of grass,

is unique yet similar to every other one" (Layman 107). No two stars are

identical in the painting, yet each is important in its relationship to

the whole. Each star has distinguishing characteristics, yet are comprised

of the same shape and colors.

The above section of "Song of Myself" is echoed in nearly every aspect

of Starry Night, and though Van Gogh himself rarely discussed this

work, Whitman's influence is hard to miss.

Conclusions

There are two other theories about Whitman's influence on Starry

Night. In her essay "Van Gogh's Starry Night and Whitman: A

Study in Source," Jean Schwind links Whitman to the painting because of

his Noon to Starry Night poems. She also examines "Prayer of Columbus,"

saying this poem and its counterpart, "Passage to India," are parallel

to Van Gogh's Starry Night and its (daytime) counterpart, Wheatfield

with Cypress. Hope Werness suggests that Starry Night shares

the cosmic consciousness of Whitman's star imagery in "When Lilacs Last

in the Dooryard Bloom'd." But the striking remnants of "Song of Myself"

in Starry Night remains the most convincing. All these theories

prove one thing: Starry Night was undeniably influenced by "the

American poems by Whitman."

"Starry Night stands out as one of the most important works of

art produced in the nineteenth century" (Brooks). The everlasting popularity

and importance of Van Gogh's painting will remain; so will the speculation

over its origin. This speculation certainly is not limited to Walt Whitman's

"Song of Myself," but the textual similarities of section 21 and Starry

Night strongly point to Whitman was an influence. And to be an influence

on one of the most important works of art produced in the nineteenth century

shows Walt Whitman impacted the visual arts world with his poetic imagery. |