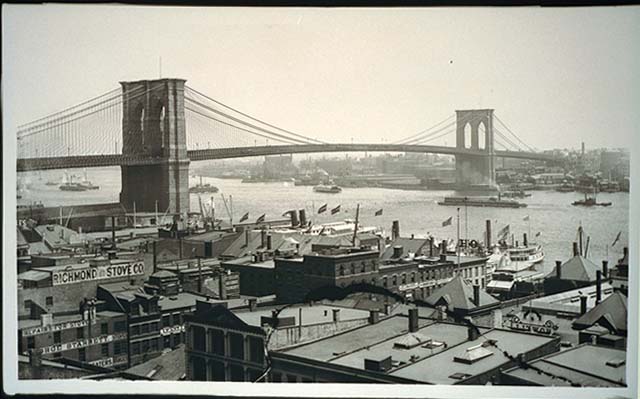

The Brooklyn Bridge, circa 1900. It is obviously

not a monument to Walt Whitman. However, as a powerful symbol, as

an icon representing an American ideal and spirit, it is relevant to the

matter at hand. A brief exploration of the bridge's history may also

be helpful in shedding light on Whitman's relevancy to bridges, and what

to make of the dedication of a Walt Whitman Bridge.

The Brooklyn Bridge was but a concept in 1800. A bridge was suggested

under a sort of Manifest Destiny spirit; a bridge across the East River,

connecting the village of Brooklyn to New York, would also thereby raise

the value of these lands on the east side of the river. At this point

in time, rural life was the inescapable norm. However, the idea of

this bridge foreshadowed a new standard; it was but a seed of the industry

and development that was on the rise. A time of urbanization, receding

rural areas, and technology was on the horizon even from this early point

in time. And it was gathering speed in its approach.

At the start of the nineteenth century, just sixty-nine years before the

construction would start on the Brooklyn Bridge, bridge building was still

in its relatively infantile stages. The biggest concern lay with

the designing of trusses, that were no longer than several hundred feet,

and were to support a moving locomotive weighing several tons (Wiedeman,

9). Suspension bridges were hardly reliable; many fell down as soon

as they were put up.

When steel was developed as a building material, the art of bridge building

took a great leap. Nevertheless, at the time that John Roebling drew

up the plans a the 3,455 foot steel suspension bridge, "nearly twice [the

length] of its nearest rival," he was taking a gamble not only on the reliability

and know-how with regard to the new material of steel, but also with the

competency of engineering.

The bridge took fourteen years to build. Construction began under

Roebling in 1869 and ended in 1883 and cost $15.5 million. The doubts

that surrounded it in the beginning, melted away upon its completion.

It was a feat, an entirely American marvel: "It should be remembered

that the Brooklyn Bridge is a 20th century bridge built by 19th century

methods. . many of the tools were the same as had been used to build

medieval Gothic cathedrals" (Weidman, 13).

When

it was complete, the Brooklyn Bridge

became a national confidence builder--

a badly

needed shot of positivism after

a civil war that

nearly ripped the country apart.

The symbol of

a bridge is not lost on anyone

who has ever

written about the Brooklyn Bridge

since.

The bridge gave 19th century Americans

a new perspective on themselves

and the world,

not unlike the perspective the

moon shot gave

us in the 20th century. For

the first time, the

average citizen could look out

over his city from

a height unattainable before.

;

(Weidman, 13)

In light of this sort of transformation, with its deep roots touching

the core of American identity, Walt Whitman has a presence. Many

of his poems express a spirit of transformation-- even going so far as

to use the metaphor of the road-- that is tied to modernization, urbanization,

the development and maturity of the country.

In Whitman's 1891-92 edition of Leaves of Grass, are these lines

from the poem "Song of the Open Road," expressing an exalted ideal of traveling

, transforming, growing, gaining new perspective. It begins with

a rural dirt road, a "brown path," and then move to the city, exalting

all along the way (Trachtenberg, 14).

Section one begins:

Afoot and light-hearted I take to

the open road,

Healthy, free, the world before

me,

The long brown path before me leading

wherever I choose.

Henceforth I ask not good-fortune,

I myself am good-fortune,

Henceforth I whimper no more, postpone

no more, need nothing,

Done with indoor complaints, libraries,

querulous criticisms,

Strong and content I travel the

open road.

Whitman professes a confidence in traveling down

this road towards change. He is about to come upon a new sort of

landscape; he crosses a bridge, in a manner of speaking. It is a

significant change in the road, and marks a critical point in the journey.

One might say it is a point of literal and figurative transformation.

Section three progresses:

You flagg'd walks of the cities!

you strong curbs at the edges!

You ferries! you planks and posts

of wharves! you timber-lined

sides! you distant

ships!

You rows of houses! you window-pierc'd

facades! you roofs!

You porches and entrances! you

copings and iron guards!

You windows whose transparent shells

might expose so much!

You doors and ascending steps!

you arches!

You gray stones of interminable

pavements! you trodden crossings!

Whitman's poetry is in step with the evolving, the transforming, the ever

shifting tide of change. This change may be viewed in personal terms,

as in personal growth; however, it may also be interpreted from the stand-point

of technology. With the exultant catalogue of early modern,

urban elements of the city, Whitman reveals an excitement, an optimism

for a wider sense of progress, similarly found with regard to the Brooklyn

Bridge.

The same points can be applied to Whitman's cultural image today.

Popularly speaking, he was more shunned than embraced for his poetry during

his time. The real value of this work, however, has unfolded

over time. Just as skeptics doubted the construction of the Brooklyn

Bridge, but later embraced it as it proved functional and awe-inspiring,

and later came to use it as a screen upon which they could project their

ideals, the same can be said of Walt Whitman.

On the other hand, all this conjecture of symbolism, of parallels, linking

the cultural roles of Whitman and the Brooklyn Bridge, or to Whitman to

bridges in general, may be bunk in light of the Walt Whitman Bridge, which

spans Gloucester, New Jersey and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. . .