Sunday, April 15, 1888.

Sunday, April 15, 1888.

To W.'s in the forenoon. "I'm going up to Tom's for tea—you will be there?" He was trying on a new red tie. "Red has life in it—our men mostly look like funerals, undertakers: they set about to dress as gloomy as they can."

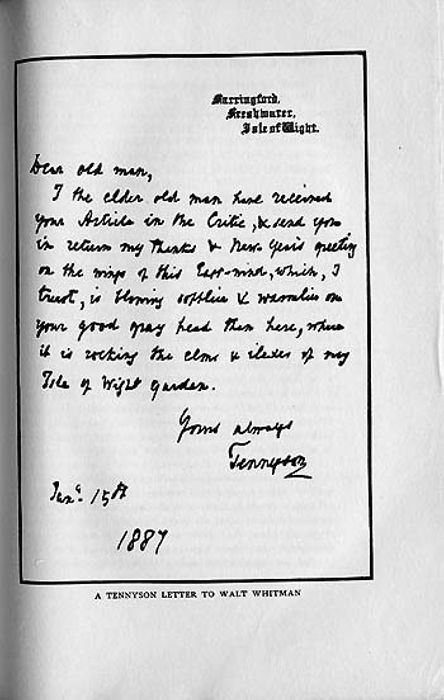

As I was about leaving W. said suddenly: "By the way, I have found the Tennyson letter I promised you. [See indexical note p036.2] Take it along—take good care of it: the curio hunters would call it quite a gem." [W. borrowed this letter back from me several times in after years and several times sent people to me to look at it.] "Tennyson has written me on a number of occasions—is always friendly, sometimes even warm: I don't think he ever quite makes me out: but he thinks I belong: perhaps that is enough—all I ought to expect." I read the letter. "It is a poem," I said. "Or better than a poem," added W. "Tennyson is an artist even when he writes a letter: this letter itself is protected all round from indecision, forwardness, uncertainty: it is correct—choice, final."

A Tennyson Letter to Walt Whitman

Farringford, Freshwater, Isle of Wight

Jany. 15th, 1887.

Dear old man,

A Tennyson Letter to Walt Whitman

Farringford, Freshwater, Isle of Wight

Jany. 15th, 1887.

Dear old man,

[See indexical note p037.1] I the elder old man have received your Article in the Critic, and send you in return my thanks and New Year's greeting on the wings of this east-wind, which, I trust, is blowing softlier and warmlier on your good gray head than here, where it is rocking the elms and ilexes of my Isle of Wight garden.

Yours always Tennyson.[See indexical note p037.2] Later at Harned's. No strangers present. "With each month that passes I feel more and more uncertain on my pins." "But you don't worry about the pins as long as you are all right at the top?" "I don't worry either way. But I guess I am all right at the top—at least as near right as Walt Whitman ever was: you know how crazy I have always been to some people."

W. talked with us in the parlor a long time. [See indexical note p037.3] "When I got up Monday morning last I had three sets of verses in hand. I sent one to the Herald, one to the Century and one to the Cosmopolitan. The Century folks sent me a check at once. The piece sent to the Herald was used according to our standing arrangement. The Cosmopolitan editor rejected me. He wrote a note saying the poem did not attract him—he suggested that I should submit other matter." The poem refused was To get the final Lilt of Songs.

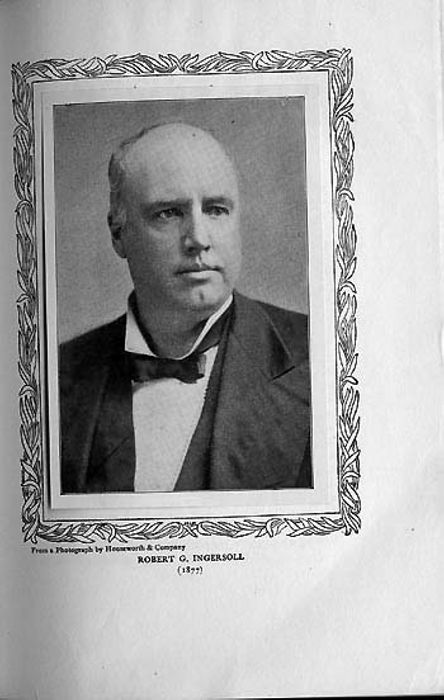

[See indexical note p037.4] W. got hold of a San Francisco portrait of Ingersoll from Harned's mantel and regarded it long and intently. "That is a grand brow: and the face—look at the face (see the mouth): it is the head, the face, the poise, of a noble human being. America don't know today how proud she ought to be of Ingersoll." Harned read aloud some paragraphs from Ingersoll's North American Review paper on Art and Morality. W. exclaimed: "Don't stop there, Tom: read it all— read it all." And several times in H.'s pauses W. cried out: "Go on! Go on!" When H. was through W. said: "I'm sorry there's no more, though I guess he has said all: it's every bit fine, every bit. A little of it here and there I might say no to, but I guess my no wouldn't be very loud." [See indexical note p038.1] W. said: "Ingersoll's gone to New York to live." "Yes," replied H., "it's the Lord's own country." "But say, Tom" retorted W., "isn't it a sort of delirium tremens?" Then he reflected: "I used to love it. Perhaps it'll do from seven or eight to fifty or sixty—but not before, not after!"

"What do you think?" W. asked: "I've received an invitation to embark on a lecturing tour in England—a real invitation with dollars, pounds, back of it. [See indexical note p038.2] Of course, it's impossible, but it's interesting. My friends here and there, both sides, do not realize how badly broken up I am. Another thing. Hollyer, over there in New York, who is getting up some etchings of the writers—Carlyle, Whittier, Longfellow, Tennyson, and so forth—has written me for my portrait, sending along some specimens of his work, with which I am but little impressed. [See indexical note p038.3] I assented to his request and sent him a copy of what Mary Smith calls the Lear picture: you all know it. Of course I am a lot curious and very little certain about Hollyer."

[See indexical note p038.4] At the table W. raised his glass before the others had done so and glancing at the picture of Lincoln on the wall opposite exclaimed: "Here's to the blessed man above the mantel!" and then remarked: "You know this is the day he died."

"After my dear, dear mother, I guess Lincoln gets almost nearer me than anybody else." W. borrowed Boswell's Johnson from Harned, saying: "I have never so far read it."

[See indexical note p038.5]

"Tom," he said, "when I was out in the carriage I picked up a lame fellow on the road—a sort of tramp, limpsy, hungry, a bit dirty, but damned human,

Robert G. Ingersoll (1877)

much like your uncle here, bless his buttons!" H. exclaimed: "Walt—that sentence is as good as a sermon." W. put on a look of mock inquiry: "Is that all it's worth—is that the best you can say of it?"

Robert G. Ingersoll (1877)

much like your uncle here, bless his buttons!" H. exclaimed: "Walt—that sentence is as good as a sermon." W. put on a look of mock inquiry: "Is that all it's worth—is that the best you can say of it?"

W. is writing about Hicks. Morse, now in the west, has made and sent W. a copy of a Hicks bust. W says: "The box is still unopened. [See indexical note p039.1] I told Sidney I was writing a Hicks piece which I would deliver in a lecture and give to Lippincott's to print (Will Walsh says he wants it). The bust has been along two or three weeks. I want Horace to come down with his hatchet or come down and use my hatchet and open the box."

Eakins' portrait of W. being mentioned, W. said: "It is about finished. Eakins asked me the other day: 'Well, Mr. Whitman, what will you do with your half of it?' I asked him: 'Which half is mine?' Eakins answered my question in this way: 'Either half,' and said again regarding that: 'Somehow I feel as if the picture was half yours, so I'm going to let it be regarded in that light.' [See indexical note p039.2] Neither of us at present has anything to suggest as to its final disposition. The portrait is very strong—it contrasts in every way with Herbert Gilchrist's, which is the parlor Whitman. Eakins' picture grows on you. It is not all seen at once—it only dawns on you gradually. It was not at first a pleasant version to me, but the more I get to realize it the profounder seems its insight. I do not say it is the best portrait yet—I say it is among the best: I can safely say that. I know you boys object to its fleshiness; something is to be said on that score; if it is weak anywhere perhaps it is weak there—too much Rabelais instead of just enough. Still, give it a place: it deserves a big place. [See indexical note p039.3] I seem to be in great request for portraits just now. The last request was from Warren Miller—he is in Brooklyn—who wants to know whether I will give him some sittings for a portrait in oil. I told him I would—yes, I would."

When W. was leaving H. said: "I hope you have enjoyed yourself today enough to come again." [See indexical note p040.1] W. replied merrily: "Better than that, I have enjoyed myself today enough to hate to go at all."