Saturday, May 5, 1888.

Saturday, May 5, 1888.

7.30 P.M. Found Harned at W.'s with Corning, candidate for the pulpit of the Unitarian church on Benson street. W. in a questioning mood. [See indexical note p102.2] "I like to cross-examine," said W. to me, once, "but I don't like to be cross-examined." He was in a mood to cross-examine. He found Corning a willing witness. C. told W. he had spent ten years travelling in Europe. He was particularly interested in Greek art. W. quizzed him freely. After he was gone W. said: "He was talkative enough but I like his voice. I am particularly susceptible to voices: voices of range, magnetism: mellow, persuading voices. [See indexical note p102.3] Corning hadn't much intrinsically to say, but his voice was worth while." W. asked Corning: "And what may be the subject of your sermon tomorrow? "My subject? Why—the tragedy of the ages." "And what may be the tragedy of the ages?" "The crucifixion." "What crucifixion?" "The crucifixion of Jesus, of course." "You call that the tragedy of the ages?" "Yes—what do you call it?" "It is a tragedy. [See indexical note p102.4] But the tragedy? O no! I don't think I would be willing to called it the tragedy." "Do you know any tragedy that meant so much to man?" "Twenty thousand tragedies—all equally significant." "I'm no bigot—I don't think I make any unreasonable fuss over Jesus—but I never looked at the thing the way you do." "Probably not. But do it now—just for once. Think of the other tragedies, just for once: the tragedies of the average man—the tragedies of every-day—the tragedies of war and peace—the obscured, the lost, tragedies: they are all cut out of the same goods. [See indexical note p103.1] I think too much is made of the execution of Jesus Christ. I know Jesus Christ would not have approved of this himself: he knew that his life was only another life, any other life, told big; he never wished to shine, especially to shine at the general expense. Think of the other tragedies, the twenty thousand, just for once, Mr. Corning." C. said: "I have no doubt all you say is true. You would not find me ready to quarrel with your point of view." W. laughed quietly. "The masters in history have had lots of chance: they have been glorified beyond recognition: now give the other fellows a chance: glorify the average man a bit: put in a word for his sorrows, his tragedies, just for once, just for once." [See indexical note p103.2] Corning said: "You ought to be in that pulpit instead of me, tomorrow, Mr. Whitman. You would tell the people something it would do them good to hear." "I am not necessary," replied W. graciously: "You have the thing all in yourself if you will only let it out. We get into such grooves—that's the trouble—passing traditions and exaggerations down from one generation to another unquestioned. After awhile we begin to think even the lies must be true."

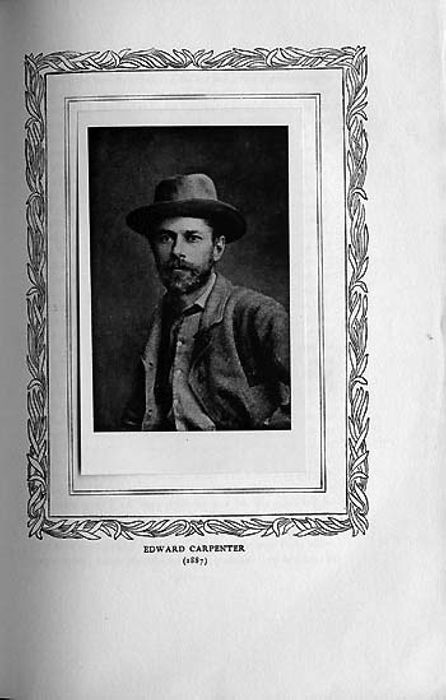

I had the waistcoat with me. It is knit, in red silk, and much too small for W. He examined it critically and said little. [See indexical note p103.3] "I suppose it will never be of the least practical use to me. The Lady Mount Temple meant well but hardly used good judgment. She must have made a guess on my size and guessed wrong." He said he had received two books from authors today—one from Harriet Prescott Spofford, Ballads about Authors, and another from Edward Carpenter, Songs of Labor. "Mrs. Spofford, as well as Dick Spofford, her husband, are good friends of mine; in fact, I have been told that at a meeting in Boston she declared openly that Walt Whitman had said the right thing in the right way about woman and her sphere—about sex—as no other writer in history has done. [See indexical note p104.1] This was a bold thing—a very bold thing. I do not know that she endorses me but she is that much and more my friend. The other Spofford, A. R., [the Librarian then at Washington], does not admit me. [See indexical note p104.2] I mean by that that he has no use for me—that he suspects my work, sees no excuse for it. He throws nothing in my way, but he does nothing to welcome me. I don't blame him—I am only putting down history for you to study—Whitman history. Spofford opposed when he might have benefited me." "Did I say I got a book from Edward Carpenter today? [See indexical note p104.3] O yes—so I did. Carpenter is a man of means on whom his estate sits lightly: is intensely interested in the radical problems: is of a religious nature—not formally so, but in atmosphere. He has been here to see me. I think he has given his book a Whitmanesque odor. He is ardently my friend—ardently. He will yet cut a figure in his own country. He is now just about climbing the hill: when he gets up to the top people will see and acknowledge him." [See indexical note p104.4] Someone asked W. whether Caird and Shairp had ever paid him their respects. "You have been so generally acknowledged in England." "Hardly by that class: I must seem like a comical, a sort of circus, genius to men of the severe scholarly type. I am too different to be included in their perspective."

Matthew Arnold's Milton address appears in the Century. [See indexical note p104.5] W. discussed it: "When you talk to me of 'style' it is as though you had brought me artificial flowers. Awhile ago, when I could get out more, I used to stop at Eighth street there, near Market, and look at the artificial flowers made with what marvellous skill. But then I would say: What's the use of the wax flowers when you can go out for yourself

Edward Carpenter (1879)

and pick the real flowers? That's what I think when people talk to me of 'style,' 'style,' as if style alone and of itself was anything. I have tried to be just with Arnold: have taken up his books over and over again, hoping I would at last get at the heart of him—have given him every sort of chance to convince me—taking him up in different moods, thinking it might possibly be the mood that prejudiced me. [See indexical note p105.1] The result was always the same: I was not interested: I was wearied: I laid the book down again: I said to myself: 'How now, why go any further with a thing that in no way either assists or attracts you?'"

"Speaking of style in that way," I said, "makes me think of something Lincoln said about policy—that it was his policy to have no policy."

"That's just it," exclaimed W. delightedly: "the style is to have no style."

[See indexical note p105.2] W. called my attention to some newspaper criticisms of his books. "All such criticisms, such threats, such warnings, go to show how necessary it is to leave the poems just as they are—to keep them intact: to weather out all the objections, sincere and insincere. The poems are not only fit for the future—they are also fit for today. Today is their day—I stick to it, is their day." Again: "You can detach poems from the book and wonder why they were written. But if you see them in their place in the book you know why I wrote them."

Edward Carpenter (1879)

and pick the real flowers? That's what I think when people talk to me of 'style,' 'style,' as if style alone and of itself was anything. I have tried to be just with Arnold: have taken up his books over and over again, hoping I would at last get at the heart of him—have given him every sort of chance to convince me—taking him up in different moods, thinking it might possibly be the mood that prejudiced me. [See indexical note p105.1] The result was always the same: I was not interested: I was wearied: I laid the book down again: I said to myself: 'How now, why go any further with a thing that in no way either assists or attracts you?'"

"Speaking of style in that way," I said, "makes me think of something Lincoln said about policy—that it was his policy to have no policy."

"That's just it," exclaimed W. delightedly: "the style is to have no style."

[See indexical note p105.2] W. called my attention to some newspaper criticisms of his books. "All such criticisms, such threats, such warnings, go to show how necessary it is to leave the poems just as they are—to keep them intact: to weather out all the objections, sincere and insincere. The poems are not only fit for the future—they are also fit for today. Today is their day—I stick to it, is their day." Again: "You can detach poems from the book and wonder why they were written. But if you see them in their place in the book you know why I wrote them."

Mail not very heavy just now. "Mostly requests for autographs, which, as a rule, I do not send." [See indexical note p105.3] Had been out for a drive. "I feel in much better feather today—I was out and happy in being out. I am an open air man: winged. I am also an open water man: aquatic. I want to get out, fly, swim—I am eager for feet again! But my feet are eternally gone." I happened to say to W.: "I will be honest. I don't care much for Milton or Dante." [See indexical note p105.4] W. laughed: "I'll be honest, too. I don't care for them either. I like the moderns better. I agree with you that Millet says more, much more, to us today than Raphael or the medieval painters. He is more immediate—I can feel his presence; he is no half mythical personage: he is a living man." [See indexical note p106.1] This, too, is from W.: "The world is through with sermonizing—with the necessity for it: the distinctly preacher ages are nearly gone. I am not sorry." W. had been reading Heine again—The Reisebilder. "I have the book here: it is good to read any time—Heine is good for almost any one of my moods. [See indexical note p106.2] And that reminds me: the best thing Arnold ever did was his essay on Heine: that is the one thing of Arnold's that I unqualifiedly like."

I had been seeing Verdi's Otello. "Is it our opera—the vocalism of the new sort? or is it still the old business lingering on?" "It is both, though mostly new." "Good—we have rather expected Verdi to do heroic things." [See indexical note p106.3] "I thought you liked the old operas—preferred them?" "I do like them—at least, I did—but their age is gone: we require larger measures, in music as in literature, to express the spirit of this age."

Touched upon a practical item. "I have been sending monthly bills to the Herald but tired of it—it seemed so commercial. [See indexical note p106.4] May 1st I did not do so. Yet the check came. They are very systematic—they have treated me handsomely. You sometimes hear me tell the truth about the editors who turn me face down, kick me out, advise me to go to a nunnery: now I am telling you of an opposite case—of another editor, who can find some wood for me to saw." As I was getting ready to go W. handed me an envelope: "Here's another little scribble from Joaquin—it has several fine little touches—one especially sweet to me towards the end. [See indexical note p106.5] You see, I too can be flattered—I too may give in. Why should we resent any honest friendliness? If a fellow don't give up his soul to get it, why is it not squarely his, to be cherished, for comfort, solace? the real capital is love, after all: just love. Take Miller along with you." I took Miller along. This is the letter:

Easton, Pa., Sept 30, 71. My dear Mr. Whitman:[See indexical note p107.1] I have many messages for you from your friends in Europe which I promised and so much desired to deliver face to face: and day after day and week after week I promised myself and hoped to come to you, but now I shall not see youtill I return; for I am tired of towns and tomorrow set my face to the West. I am weary and want rest, and I cannot rest in cities. My address for a time will be San Francisco and since I cannot see you I should be proud of a letter from you. I am tired of books too and take but one with me; one Rossetti gave me, a Walt Whitman—Grand old man! [See indexical note p107.2] The grandest and truest American I know, accept the love of your son,

Joaquin Miller.