Sunday, January 20, 1889.

Sunday, January 20, 1889.

2.30 P. M. W. sitting in his usual place. Neither reading nor writing—yet not dozing: hands folded across his stomach—seeming to be lost in thought. Particularly affectionate somehow to-day. Some of his mail down by his feet: letter and paper for Bucke: spoke of these. "I finished my letter, as I told you, last night: put it up: there it is: and The Critic, too: I think he will like to receive that: Maurice has a curious affinity for all the odds and ends Whitmanesque." Then he turned a questioning eye upon me: "How would Kennedy do? Could it have been Kennedy?" And when I looked quizzically at him: "Oh! I mean for The Critic piece: could he have written it? I have been running it over in my mind all the forenoon." I said "me too": I too had wondered about Kennedy: but I doubted if Kennedy had access to The Critic. W. said: "Oh yes! he has that: Kennedy is not closed out: I don't know but he is liked there: at any rate it might be him." Then W. exclaimed: "It is not wholesale: it pulses with enthusiasm: it 's hot victuals: not warm only but hot, hot, hot!" And when I spoke of it as gracefully written: "That is true: facility in every line." But he is still dubious of criticism in general.

I said Sanborn's piece in The Republican sounded as if it was written by a man who wanted to say more. W. said: "That is very like to be the case." How did he know that Sanborn had written the letter? "I do not know: I only conclude—assume, surmise: it seems to me probably: he is the only man from whom to expect that kind of a word in that paper." Was S. cold, stately? "No: I could not say that. I could best describe him by saying he was of the Emerson stamp—modelled himself on that standard." Then after stopping: "You never met Emerson? Well, anyone who had ever met Emerson would recognize any one of the

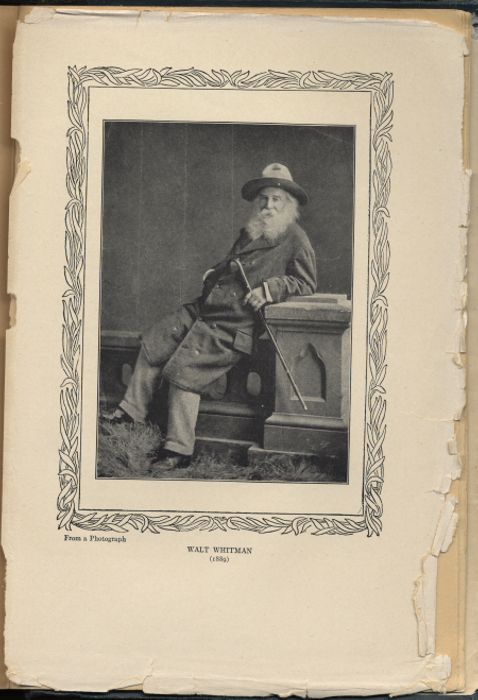

From a Photograph

From a Photograph

WALT WHITMAN

(1889)

Reproduction of a photograph of Whitman

group up there: they all more or less accept his fashion. It reminds me of something from a Voltairean—perhaps from Voltaire himself—who said that, pilgrimaging about in Christendom, you everywhere met a piece of the cross: here more, here less, of it: till finally getting to Rome you come upon the whole cross itself. It was so with the Emersonian manner: now a piece of it, then a piece of it, finally coming to Emerson himself—there the whole genuine beautiful efflux, of which you had only caught scents, glints, glimpses, before."

The Press this morning, under a display headline, The Flag Insulted gave a long sensational account of our Samoan difficulties with Germany. W. had read. Did it mean war, "Oh no! The Press makes a big noise: we will not be frightened or angered by it. I read The Press every day: it has all the news (a good deal more, too!)—all the news: but along with what's excellent in journalism it illustrates—illustrates better than any paper I know on the list—the dangers, pettinesses, possible in the profession. The man inside there—the fellow hired on the little editorials, witty pieces—evidently mistook his vocation. My objection to The Press is, that it is narrow, superficial: horribly flippant, arrogant, ignorant." I thought that a very severe arraignment. "Yes, it is: but it applies there." Why not to other papers too? Most of them? "Yes—more or less to others too, but to The Press most of all." Gave me back The Stage. "I have read it through: I always do."

It commenced to snow about noon: now snowing hard and lying: the first snow storm practically of the season. W. asked: "Was it not unusually early: it seemed to me the light came through the slats there piercingly: I wondered if it was in some way from an artificial light." We talked of the river: how the river is on days like this: W. interrogating. I was to go to Germantown in the late afternoon. "Ah!" and after a slight wait: "Well, if you meet out there with any inquiring friends, tell them Walt Whitman sends his best love—is still in his chair here: the fire briskly burning: the weeks wearing monotonously away." I said: "It 's at least half my business out there usually to talk of you." W. further: "It is very hard, very hard, having to sit here for such a period—now going on eight months—in the same room: to read a little, write a little: doze the time off into oblivion." He added: "I have been telling Eddy, I feel as if seven or eight hundred pounds were tied to me, to be borne about, borne with, and that not only physically but mentally, with my brain, as well." I wrote Bucke—now he is almost on the eve of his visit at last—that we little thought back in the summer that the three of us would meet here again in this way. W. listened. "Nor did we: there were doubtful days indeed!" Had he too had the same misgivings? "Yes indeed: those first days were full of seriosities." Said there was "a tied-up pile" of Passage to India on top shelf in the little room. I went in. Got down the package he indicated. He sat still—examined: there were about a dozen. "But all Democratic Vistas! Why, I did not know I was so rich in them!" Tied them up again. Put them back. Found P. to I. He took a copy—wrote in it: "Horace Traubel from Walt Whitman, Jan 20 '89." Had often promised me such a perfect copy.

Harned stopped at the door this noon. Left Tribune. Met Gilchrist at Eighteenth and Arch yesterday. W. "glad to hear of him." "He has not been over for several weeks." Referred to The Critic once again—the review—as "having no dubiosities whatever." Ed tells me of a visitor during one of W.'s bad spells: an old lady, who cried—said she "did so want to see the dear old poet." I said to W. that I thought Dave was not dissatisfied not to have his imprint on the big book. W.: "I guess he understands: I do not regret myself that the book stands as it does." He asked for my opinion. Had he "made a mistake in keeping the book thoroughly personal?" I said: "You can't help your- self: it would be personal with or without a publisher: that 's the start and finish of the book." He cried: "Good! good! so it is: the root of the matter: you have it. I wanted to make this a pet edition—to sort of let it go straight from my hands into the hands of the reader: from my heart to your heart—from me to anybody: giving us, whoever we are, strangers or friends, a direct relation—establishing us in immediate neighborliness." I said: "I suppose you say that every reader is a next door neighbor!" W. said: "I have n't said it, but now that you have said it for me I'll say it after you—adopt it." Then of a sudden he swung around to the table by the window. "Are you in a big hurry?" he asked. I said no. I was not due in Germantown till the last thing in the afternoon. He picked up an envelope. "I have found you another letter to Hugo: my letter to Hugo: a draft: one of the first drafts: I always kept the original. I would like you to read it to me before you finally take it along: to-morrow if you choose: now if you have time. We were just talking of personal things—of the Leaves—the complete book: we insist upon the personal: well, you have it in these letters too: they, too, demonstrate me—my theory, philosophy, what I am after: they too. If you want to know what I mean watch what I do. Did you say you had time to read the letter to-day? Do it then: I have time to listen to it." The envelope was indited: "To Hugo Oct 8 '63." The letter was written on four different sized sheets of paper. On the reverse of one of the sheets was this note in W.'s hand:

Fort Bennet, July 21st 1863.Adjutant General Thomas, General [substituted for Sir]: I have the honor to forward this my application for an officer's position in one of the Colored Regiments now forming in the District of Columbia.

I have been in the military service of the government as a private since the beginning of the War—enlisted first in the 8th New York Militia 19th April 1861, for three months—subsequently on the 25th August 1862, in the 2nd New York Artillery for three years—and am still in the regiment. I was born in the state of New York, am in sound health, & 26 years of age.

Herewith please see testimonials from my officers —

I have the honor General to remain &c Samuel S. Freyer, Co E 2nd New York Vol. Artillery."Yes," said W.: "I wrote hundreds of such, similar, letters for the boys: letters for their friends—for their folks: fathers, mothers, sweethearts: they were too sick to write, or not sure of themselves, or something: why, I even said their prayers for them—some of them. What did n't I do? I had n't noticed that letter on the back of the sheet: I 'm glad, however, that you read it: it was, it is, a part of the story. But read the big letter: read it: then I 'll let you go—you and the letter together."

Dear Hugo. I don't know why I have delayed so long as a month to write to you, for your affectionate and lively letter of September 5th gave me as much pleasure as I ever received from correspondence. I read it even yet & have taken the liberty to show it to one or two persons I knew would be interested. Dear comrade, you must be assured that my heart is much with you in New York, & with my other dear friends, your associates—& my dear I wish you to excuse me to Fred Gray & to Perk, & Ben Knower, for not yet writing to them, also to Charley Kingsley, should you see him—I am contemplating a tremendous letter to my dear comrade Frederickus, which will make up for deficiencies,—my own comrade Fred, how I should like to see him and have a good heart's time with him, & a mild orgie, just for a basis, you know, for talk & interchange of reminiscences & the play of the quiet lambent electricity of real friendship—O Hugo, as my pen glides along writing these thoughts, I feel as if I could not delay coming right off to New York & seeing you all, you & Fred & Bloom, & everybody—I want to see you, to be within hand's reach of you, and hear your voices, even if only for one evening for only three hours—I want to hear Perk's fiddle—I want to hear Perk himself, (& I will humbly submit to drink to the Church of England)—I want to be with Bloom (that wretched young man who I hear continually adorns himself outwardly, but I hear nothing of the interior) and I want to see Charley Russell, & if he is in N. Y. you see him I wish you to say that I sent him my love, particular, & that he & Fred & Charles Chauncey remain a group of itself in the portrait-gallery of my heart and mind yet & forever—for so it happened for our dear times, when we first got acquainted, (we recked not of them as they passed,) were so good, so hearty, those friendship times, our talk, our knitting together, it may be a whim, but I think nothing could be better or quieter & more happy of the kind—& is there any better kind in life's experiences? —

Dear comrade, I still live here as a hospital missionary after my own style, & on my own hook—I go every day or night without fail to some of the great government hospitals—O the sad scenes I witness—scenes of death, anguish, the fevers, amputations, friendlessness, hungering & thirsting young hearts, for some loving presence—such endurance, such native decorum, such candor—I will confess to you dear Hugo that in some respects I find myself in my element amid these scenes—shall I not say to you that I find I supply often to some of these dear suffering boys in my presence & magnetism that which nor doctors, nor medicines, nor skill, nor any routine assistance can give? Dear Hugo, you must write to me often as you can, & not delay it, your letters are very dear to me. Did you see my newspaper letter in N Y Times of Sunday Oct 4? About my dear comrade Bloom, is he still out in Pleasant Valley? Does he meet you often? Do you & the fellows meet at Gray's or anywhere? O Hugo I wish I could hear with you the current opera—I saw Devereux in the N Y papers of Monday announced for that night, & I knew in all probability you would be there—tell me how it goes, & about the principal singers—only don't run away with that theme, & occupy too much of your letter with it—but tell me mainly about all my dear friends, & every little personal item, & what you all do, & say &c.

I am excellent well. I have cut my beard short & hair ditto: (all my acquaintances are in anger & despair & go about wringing their hands) my face is all tanned & red. If the weather is moist or has been lately, or looks as if it thought of going to be, I perambulate this land in big army boots outside & up to my knees. Then around my majestic brow around my well-brimmed felt hat—a black & gold cord with acorns. Altogether the effect is satisfactory. The guards as I enter or pass places often salute me. All of which I tell, as you will of course take pride in your friend's special & expanding glory.

Fritschy, I am writing this in Major Hapgood's office, fifth story, by a window that overlooks all down the city, & over & down the beautiful Potomac, & far across the hills & shores for many a mile. We have had superb weather lately, yes for a month—it has just rained, so the dust is provided for, (that is the only thing I dread in Washington, the dust, I don't mind the mud). It is now between one and two o'clock Thursday afternoon. I am much alone in this pleasant far-up room, as Major is absent sick, & the clerk lays off a good deal. From three to five hours a day or night I go regularly among the sick, wounded, dying young men. I am enabled to give them things, food. There are very few visitors, amateurs, now. It has become an old story. The suffering ones cling to me poor children very close. I think of coming to New York quite soon to stay perhaps three weeks, then sure return here.

W. was quiet for a few minutes after I stopped reading. I put the letter in its envelope and both into my pocket. "That 's right," said W., "now it 's yours." He was serious: "The letters, my letters, sent to the boys, to others, in the days of the War, stir up memories that are both painful and joyous. That was the sort of work I always did with the most relish: I think there is nothing beyond the comrade—the man, the woman: nothing beyond: even our lovers must be comrades: even our wives, husbands: even our fathers, mothers: we can't stay together, feel satisfied, grow bigger, on any other basis." I said: "That picture of you in the sojer clothes is delicious." He laughed very heartily over it. "Ain't it, now? Well—I should say so: I could have passed for an understudy—for Thomas, Rosecrans, Meade: O yes! I must have presented a wonderful front as I stalked about dressed to kill—an N. P. Willis in the uniform of the Grand Army of the Republic!" Then again: "I was always between two loves at that time: I wanted to be in New York, I had to be in Washington: I was never in the one place but I was restless for the other: my heart was distracted: yet it never occurred to me for a minute that there were two things to do—that I had any right or call to abandon my work: it was a religion with me. A religion? Well—every man has a religion: has something in heaven or earth which he will give up everything else for—something which absorbs him, possesses itself of him, makes him over into its image: something: it may be something regarded by others as being very paltry, inadequate, useless: yet it is his dream, it is his lodestar, it is his master. That, whatever it is, seized upon me, made me its servant, slave: induced me to set aside the other ambitions: a trail of glory in the heavens, which I followed, followed, with a full heart. When once I am convinced I never let go: I had to pay much for what I got but what I got made what I paid for it much as it was seem cheap. I had to give up health for it—my body—the vitality of my physical self: oh! much had to go—much that was inestimable, that no man should give up until there is no longer any help for it: had to give that up: all that: and what did I get for it? I never weighed what I gave for what I got but I am satisfied with what I got. What did I get? Well—I got the boys, for one thing: the boys: thousands of them: they were, they are, they will be mine. I gave myself for them: myself: I got the boys: then I got Leaves of Grass: but for this I would never have had Leaves of Grass—the consummated book (the last confirming word): I got that: the boys, the Leaves: I got them."

He had fired up. Looked almost defiant. "All the wise ones said: 'Walt you should have saved yourself.' I did save myself though not in the way they meant: I saved myself in the only way salvation was possible to me. You look on me now with the ravages of that experience finally reducing me to powder. Still I say: I only gave myself: I got the boys, I got the Leaves. My body? Yes—it had to be given—it had to be sacrificed: who knows better than I do what that means? As to that, Horace, look here: here 's a dirty slip of paper I was re-reading to-day." He reached forward, picked up a soiled stained sheet of blue paper on which was some of his writing. "Read it," he said, handing it to me: "it falls in with what we have been talking about." I read this, aloud:

"Perfect health is simply the right relation of man himself, & all his body, by which I mean all that he is, & all its laws & the play of them, to Nature & its laws & the play of them. When really achieved (possessed) it dominates all that wealth, schooling, art, successful love, or ambition, or any other of life's coveted prizes, can possibly confer, & is in itself the sovereign & whole & sufficient good, & the inlet & outlet of every good. In perfect health (a far, far different condition from what is generally supposed—indeed few minds seem to have the true & full conception of it)—sometimes I think it is the last flower and fruitage of civilization & art, & of the best education."

I said to W.: "I see: you knew all that: you had to give that up: you have no regrets." "No regrets: none: it had to be done." I said: "Walt, you gave up health great as health is for something even greater than health." He said: "Horace, that 's what it means if it means anything."