Pete the Great: A Biography of Peter Doyle

Peter George Doyle's importance in the emotional life of Walt Whitman is well established. The romantic friendship that sprang up in 1865 between the streetcar conductor and the poet spanned the years of Whitman's residence in Washington, D.C, and continued nearly up through Whitman's death in Camden, in 1892. Yet despite the prominent role that Doyle played in Whitman's life, our knowledge of his personal history is incomplete. The following biography fills in some of the missing pieces about this enigmatic figure.1 In so doing, it hopes to give voice to the man John Burroughs hailed as "a mute inglorious Whitman."2

A Boyhood in Ireland and Passage to America

Until now, Doyle's actual birthday was a mystery to Whitman biographers. Peter Doyle himself claimed that he "was born in 1847, in Ireland." 3 Whitman thought Doyle was born in Limerick on June 3, 1845, 4 while Pete's death certificate gave 1848 as his year of birth (NUPM, 2: 891). To settle the question, I engaged Dr. S.C. O'Mahony of the Limerick Regional Archives to search for Doyle's baptismal record.5 O'Mahony found that Peter Doyle was baptized in the parish of St. John the Baptist Roman Catholic Church, Limerick City, Ireland on June 16, 1843.6 Presumably, Pete would have been baptized soon after his birth, as was the custom in those days. In that case, we can reasonably ascribe to Doyle a birth date of June 3, 1843.

Figure 1.

Limerick, Ireland, on the banks of the Shannon, the birthplace of Peter Doyle.

Figure 1.

Limerick, Ireland, on the banks of the Shannon, the birthplace of Peter Doyle. - John, baptized May 16, 1831;

- Francis Michael, born on September 29, 1833;

- John, baptized June 29, 1836 (evidently the eldest boy died before this son was born);

- James, baptized July 17, 1839;

- Elizabeth, baptized September 30, 1842;

- Peter, baptized June 16, 1843;

- Mary, baptized April 8, 1846;

- Edward, baptized May 28, 1849; and

- Margaret, born in Virginia in 1853.,

Doyle claimed that he "was about two years old when brought to America" (Bucke, 21–22). A note Whitman made about Doyle, however, stated that Pete "came to America aged nearly 8 in March 1853 The heavy storm & danger Good Friday night—1853—almost a wreck" (NUPM, 2: 821). Whitman recollected that Doyle was "a bright-eyed little fellow—and the sailors took to him a good deal, as sailors do. 9

Both Whitman and Doyle were slightly off the mark in their dating of Doyle's arrival. Peter Doyle was eight years old when he came to the United States from Ireland in May 1852. He emigrated with his mother and brothers, John, James, and Edward. Their names can be found on the passenger list for the vessel William Patten. The ship, originating in Liverpool, England, arrived in Baltimore, Maryland on May 10, 1852. 10

Charles Theobald captained the full-rigged sailing ship that carried the family to America.11 The ship was nearly wrecked at sea, as Whitman noted. The May 10, 1852, edition of the Baltimore Sun stated that the vessel had "experienced a continued succession of easterly gales since April 1st; had bulwarks, stove, bowsprit carried away, &c." The Good Friday storm to which Whitman referred, would have occurred on April 9.

Presumably, Doyle's father and his brother, Francis Michael, came to this country at an earlier date. They were not listed as passengers on the William Patten. Perhaps Peter's sisters, Elizabeth and Mary, were victims of the Great Hunger that engulfed Ireland in the late 1840's. There is no record that the girls ever joined the other family members in America.

Hometown Alexandria, VA

Peter Doyle stated that his family spent its first years in America living in Alexandria, Virginia (Bucke, 22). This river port city on the Potomac is a few miles south of Washington, D.C. Catherine's brother, Michael Nash, lived in the District of Columbia, and probably influenced the Doyles' decision to settle in that area. The youngest Doyle child, Margaret, was born in Alexandria around 1853.

Peter Doyle, Sr. was a blacksmith (Bucke, 22). A likely place of employment was the Smith and Perkins Locomotive Works.12 Located on the Alexandria waterfront, the works included a machine shop, a foundry building, a blacksmith shop, a boiler shop, and a car shop. Smith and Perkins built coal-burning locomotives, at the rate of three per month, for railroads that included the Baltimore & Ohio, Pennsylvania Railroad, Manassas Gap, and Hudson River companies. In 1852, the company employed some 200 men in its operations.

The social life of an Irish Catholic family like the Doyles would have been centered on St. Mary's parish. The original church building, still in use in 1994, was consecrated on March 4, 1827.13 Church tradition states that George Washington was an early benefactor, contributing to the building fund at the chuch's inception on July 14, 1793. The parish's first pastor, John Thayer, was a Boston native. Thayer had served Washington's Colonials as a Protestant minister before his conversion to Catholicism. Father Thayer's ministry led him eventually to St. John's in Limerick, Ireland. He lived there from 1803 until his death on February 5, 1815.14 It's likely that as children, Peter, Sr. and Catherine Nash, had heard Thayer speak of his Alexandria parish in Sunday sermons.

During the 1850's, St. Mary's was a mission church staffed by the Jesuits of Georgetown College. Pete may have learned to read and write at the parish's Sunday school for boys.

Doyle stated that the family left Alexandria in 1856-57 when "bad times came on" (Bucke, 22) during the general national depression. If his father worked for Smith and Perkins Locomotive Works, he would have lost his job when the firm declared bankruptcy in 1857 (Smith & Miller, 77). Extant Alexandria municipal records list Peter Doyle as paying taxes in 1856 and 1858. This suggests that the family moved in 1858 or 1859. Doyle further remarked that the family went to Richmond, Virginia, where Doyle's father was offered employment in an iron foundry (Bucke, 22).

According to the 1860 Richmond city directory, Doyle worked as a blacksmith for Tredegar Iron Works.15 On the eve of the Civil War, Tredegar was the largest ironmaker in the South. 16 The foundry employed eight hundred free workers and slaves, the fourth largest such employer in the United States (Dew, 20). Its free workforce consisted primarily of Irish and German immigrants (Dew, 28). During the Civil War, the Confederates relied heavily on the Tredegar works to supply it with arms. Among its many notable accomplishments during the War, it supplied the iron for the C.S.S. Virginia, better known as the Merrimac, for its historic battle with the Union ironclad, the Monitor (Dew, 118).

The 1860 Population Census for Richmond, enumerated on June 28 of that year, lists Peter Doyle, aged 47, a laborer, Catherine, aged 45, a dressmaker, and their children John, employed as a machinist, James, Peter, Edward, and Margaret.

Pete the Rebel

Doyle stated that he "was a member of the Fayette Artillery, and when the war broke out I entered the Confederate Army" (Bucke, 22). According to his Compiled Military Service Record, Doyle enlisted with the Richmond Fayette Artillery on April 25, 1861, a week and a day following the Virginia State Convention's adoption of an Ordinance of Secession on April 17. He served in the Confederate military for seventeen months, and was discharged on November 7, 1862.17 The official documents apparently inverted Doyle's first and middle names. He appears both as George P. Doyle, and as Peter Doyle. He was seventeen years old when he enlisted. Military papers described Doyle as 5 feet 8 inches tall, with blue eyes, a light complexion and light-colored hair. Doyle's civilian occupation was given as "cooper," that is, a barrel or cask maker. Doyle's company was named in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette, upon the Revolutionary War hero's visit to Richmond in July 1824.18 The company's association with Lafayette would have charmed Walt Whitman. The poet fondly remembered that, as a boy, he was "touched by the hands, and taken a moment to the breast of the immortal old Frenchman" during Lafayette's visit to Brooklyn Heights in 1825.19

As light artillery, the Richmond company provided field support for infantry units. The company's guns included four six-pounders (two of which had been used in the Revolutionary War, and were given to the company by Lafayette in 1824), two ten-pounder Parrots, and one twelve-pounder Howitzer (Moore, 14). Initially, the company consisted of one hundred and eight enlisted men and four officers (Moore, 4). Doyle was one of ten Irish natives in the battalion (Moore, 135).

The company spent a quiet first year at Gloucester Point, Virginia, opposite Yorktown (Moore, 4). During this assignment, Doyle was promoted, on October 27, 1861, from Private to Second Corporal.

On February 8, 1862, apparently as part of a reorganization of the company under the Confederate States Act, most of the company's members, including Doyle, re-enlisted for a term of two years. Doyle received a re-enlistment bounty, and a furlough to visit Richmond from February 20 through March 7.

The Peninsula Campaign

On February 22, 1862, the Fayette Artillery was ordered to Yorktown, Virginia (Moore, 9). In April, the company formed part of the Yorktown defenses as the city came under seige by General George McClellan's Union Army. McClellan's ultimate objective in the Peninsula Campaign was to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond by marching up the peninsula formed by the York and James rivers. During the Yorktown engagement, Doyle's company was under fire at Harrod's Mill on April 3, and at Wynn's Mill from April 5 until May 4 (Moore, 9).

Following the Confederates' withdrawal from Yorktown, the Fayette Artillery manned the defenses at Fort Magruder during the rear-guard battle of Williamsburg. Three of Doyle's comrades—Delaware Branch, Delaware Crafton, and George Smith— were killed during the battle, and one—Joseph Beck—died three weeks later from wounds received (Moore, 144, 146, 150, 169). Nine other men in the company were also wounded (Moore,11). Beginning with the May 1862 company roster, Doyle was listed as a Private, rather than as a 2d Corporal.

On May 31, the Fayette Artillery participated in the far-larger battle of Seven Pines, or Fair Oaks, at the gates of Richmond.20 Doyle and his comrades also took part in several battles of what would later be called The Seven Days Campaign, under a new commander, General Robert E. Lee, of what was now known as the Army of Northern Virginia. These battles were fought along the Chickahominy River, just outside the Confederate capital. The Richmond company fought at Gaines' Mill on June 27; Frayser's Farm or Glendale on June 30; and Malvern Hill on July 1 (Chamberlayne, 4). Although the latter battle was a Union victory, McClellan withdrew his army, much to President Lincoln's consternation.

The Peninsula Campaign took a heavy toll on the Fayette Artillery. Writing from Richmond on July 10, the company's 1st Lieutenant, William Izard Clopton, told his sister Joyce, "I was in all the fights on the Chickahominy & terrible ones they were—my heart sickens when I think of the gallant spirits that then fled from us for ever...Although I am unhurt, I am utterly broken down & exhausted & I am here for a few days to rest. I need it most sadly, for three months I have been thru' the most terrible service."21 In addition to those killed and wounded at Williamsburg, fourteen artillerymen were hospitalized from wounds or sickness suffered during the campaign, fifteen were AWOL at some point, and six men deserted (Moore, 143–174).

From July 11 through 23, Peter Doyle was away from camp, on a detail to track down and arrest deserters. The Fayette Artillery was called to Manassas, Virginia. However, they did not arrive in time to take part in this battle, in which the Confederates repeated the victory won there the year before (Moore, 13).

Blood and Water

The Richmond company next took part in General Robert E. Lee's Maryland Campaign. In the battles of South Mountain and Antietam that followed, Doyle's Confederates squared off against Federal forces that included Walt Whitman's brother, George Washington Whitman.

The Fayette Artillery was assigned to General Lafayette McLaws' Division. The troops crossed the Potomac near Leesburg, Virginia on September 6, 1862, and marched to Frederick, Maryland. The Confederates soon withdrew, as the Federal forces advanced from Washington, DC, and re-took the city. Along with his comrades in the 51st New York Volunteers, George Whitman passed in review of General McClellan as the brigade marched through the Western Maryland town.22

After leaving Frederick, the Richmond Fayette Artillery marched southwest. They took a position with Semmes' Brigade on South Mountain at the Brownsville Gap, just outside Burkittsville. They were engaged in battle there on September 14. Following the Confederate loss to the Union that same day in the nearby Crampton's Gap, the Fayette Artillery was summoned to Harpers Ferry, which fell to the rebels on September 15.

Meanwhile, George Whitman and the 51st New York Volunteers were also fighting on South Mountain. Whitman's company fought the enemy on the 7th of September, and again on the 14th, at Fox's Gap, approximately five miles north of Doyle's position at Brownsville Gap.23

Doyle and Whitman both saw heavy action in the battle of Antietam, (refered to as the battle of Sharpsburg by the Confederates). As part of McLaws' Division, the Fayette Artillery marched all night from Harper's Ferry to Sharpsburg. They arrived in Lee's camp with the morning sun on September 17 (Moore, 15). After a brief rest, the Division reinforced General Stonewall Jackson's beleaguered troops, who were positioned in the West Wood. McLaws' artillery, under the direction of Colonel Henry Cabell, the former captain of the Fayette Artillery, was in the heat of battle during the late morning and early afternoon.24 Lt. Clopton of the Richmond company described his feelings after this battle in a letter home: "At day-break on the 17th of September we recrossed into Maryland to re-inforce Genl. Lee & were all day long in the great battle of Sharpsburg. This was a most terrific affair & at night both parties rested on their arms completely satisifed with each other with the dead & wounded lying on the field. That is the most unnerving part of a fight to see the poor wounded fellows lying utterly helpless & to hear their agonizing groans. We should have infalibly & utterly routed the enemy but the men have straggled so much that one half our force could not be gotten into the fight. There is terrible management & I suppose the commanding Genl. is responsible.25

In another part of the battlefield, George Whitman and the 51st New York Volunteers were occupied with taking Rohrbach Bridge, across Antietam Creek, better known ever since as Burnside's Bridge, after Union General Ambrose Burnside. Their much-celebrated crossing occured early in the afternoon of the 17th (Sears, 266, 354). The Antietam National Battlefield Park today contains a monument to the men of the 51st New York, where the men took the bridge.26

Beginning that evening and continuing throughout the following day, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia withdrew to Winchester, Virginia. The Richmond company provided artillery cover for the withdrawal. These soldiers claimed to be the last to cross into Virginia (Moore, 16).

Doyle is Discharged

This day personnally appeared before me a Notary Public for the Said City in the State aforesaid, Peter Doyle, and made oath that he is not a Citizen of the Confederate States, that he was born in Ireland, in the Kingdom of Great Britain, and that he came to the Confederate States of America in the Spring of 1860, that he came from the City of Washington, D.C. where he had lived for three or four years that being the first place he stopped at after arriving in the United States. That he came to the City of Richmond, Va in the year 1860 in search of employment, and remained in the said city until 1861 when he joined the Fayette Artillery (Capt. Cabbell) for one year, and was mustered in the service of the Confederate States where he has remained ever since. That he has never acquired domicile in the said Confederacy, that he owns no property, never paid taxes nor voted in the said Confederacy, And that he has no family. He asks the Hon. Secretary of War to discharge him from the Army of the Confederate States. [signed] Peter Doyle Sworn and subscribed to before me this 14th day of Oct. 1862. V. L. Atkinson, N.P.The particulars of Doyle's testimony were supported by a John Smith who stated before Atkinson on October 14 that he had known Doyle in Washington, D.C.

And the affidant, Peter Doyle, further states on oath that he joined the Fayette Artillery, (Capt. Cabbell's company), on the 25th day of April, 1861, and that he does not intend to acquire a permanent residence in the Confederate States of America and that he intends to return to his native country, (Ireland), as soon as an opportunity will afford his doing so. [signed] Peter Doyle Sworn and Subscribed to before me this 31st day of Octr. 1862 V. L. Atkinson, N.P.

On the basis of this application, the Secretary of War granted Doyle a discharge on November 7, 1862.

Peter Doyle's statement in support of his discharge contained an equal measure of truths, and half-truths. An Irish native, Doyle could claim allegiance to the British crown, but his residence in this country was twice as long as Doyle alleged, and it is unlikely that he actually intended to return to Ireland. I found no evidence of Doyle in Washington before the War, but it is possible that he lived there for a time with his brother, Francis Michael, or his uncle, Michael Nash, before joining his parents and siblings in Richmond. A teenager, Doyle presumably owned no property. Doyle had neither wife nor offspring, but he did have a family consisting of his own parents and siblings living in the Confederate capital city.

In seeking a discharge, Doyle was probably motivated by a combination of war weariness and illness. From April through September of 1862, Doyle's company was engaged in arguably the most demanding series of battles fought during the war. Doyle's wartime service culminated in the battle of Antietam, which retains the dubious distinction of being the bloodiest single-day battle in American military history. It is possible that Doyle's battle wound was serious enough for him to feel unable to return to active service, although the hard-pressed Confederates may have been unwilling to discharge him solely on this basis. Even after Doyle received his discharge, his service record continues to show him as spending time in military hospitals. Whitman claimed that Doyle was an outpatient in Washington when the two men met (Johnston & Wallace, 147).

Despite this renunciation, Doyle maintained a strong identification with his Southern roots, and pride in his Confederate military service. He was well known to his friends as a former "Rebel." Later in life, he joined the United Confederate Veterans.

Doyle was one of five company members—Lucius Poitras, Charles Hutzler, Charles Matthias, and Andrew Baccigalupo were the other four—who were discharged in 1862 based on their claim that they had "never acquired a domicile" in the Confederate states (Moore, 144, 158, 162, 166). In particular, Poitras, a Canadian, and Baccigalupo, a Sardinian, were discharged on the basis of their claimed alien status.27 Indeed, of the 106 men who enlisted as Privates with Doyle on April 25, 1861, in the Fayette Artillery, 40 men had been discharged or had deserted by the time Doyle received his discharge in November 1862 (Moore, 143-174).

While Doyle was gaining his discharge in Richmond, the Fayette Artillery was being re-organized. On November 23, 1862, the Richmond artillery became part of a battalion under the leadership of Captain James G. Dearing, Jr (Moore, 65). A month after Pete left the military, his comrades in Dearing's (38th) Battalion took part in the battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia on December 13, 1862. A minor facial wound George Washington Whitman received from an artillery shell at this battle caused his brother Walt to rush to the battlesite from his Brooklyn home. Walt's desire to tend the wounded soldiers North and South kept him in Washington through the remainder of the war. Perhaps it was a shell lofted from Lee's Hill by one of Doyle's comrades in the Fayette Artillery that felled George Whitman, thus triggering the chain of events that resulted in Peter Doyle meeting Walt Whitman in Washington a few years later.

Although Doyle was discharged on November 7, 1862, his official military record contains several entries after this date. His name appears on the register of patients in General Hospital No. 2 in Richmond, Virginia; the record does not indicate when he was received into the hospital or for what illness he was treated, but it states that he was released on December 5, 1862. I have assumed that Doyle was wounded at Sharpsburg and admitted to the hospital shortly thereafter. This assumption is based on the fact that Doyle was in Richmond on October 14 and 31 (when he requested his discharge), while his company was at that time stationed in Winchester, Virginia. Also, Whitman stated that Doyle was wounded during the war (Johnston & Wallace, 147).

More significantly, Doyle's name appears on a March 7, 1863, record of payment, in the amount of thirty dollars, to George Wright by Major John H. Parkhill, Quartermaster of the Confederate States Army. Wright received a bounty, "For arresting and delivering to Gen. John H. Winder at Richmond, Peter Doyle, a deserter from the Fayette Artillery." It remains unclear why Doyle, who had received a discharge in November 1862, was arrested for desertion four months afterwards. One possible explanation is that Doyle's company was never officially notified of the discharge, and began proceedings against him. A second possibility is that the Richmond authorities had decided that the terms of Doyle's discharge were invalid. Doyle had claimed alien status, and expressed an intention to return to Ireland, but had remained in Virginia. In the spring of 1863, there was a crackdown on foreigners who claimed exemption from military service but who continued to remain in Virginia.28 Such aliens were ordered to produce their papers at the office of General John H. Winder, the military provost of Richmond. As a result of Winder's action, there was a large exodus of foreigners from Virginia that spring.

Doyle apparently was ordered to report back to his company, which was then stationed in Petersburg, Virginia (Moore, 67). The records of the Confederate States Hospital in Petersburg stated that a Peter Doyle of Dearing's Battalion (the battalion into which the Fayette Artillery was subsumed) was admitted on March 19, 1863. The records further stated that Doyle was released on April 17, to return to duty. At the time of his release from the hospital, Doyle's company was on duty in Suffolk, Virginia (Moore, 68-71). According to extant company muster rolls, Doyle never rejoined his outfit.29

"Prison-escaping"

What happened next to Doyle? In the Bucke interview, Doyle stated, "Being taken prisoner, happening in Washington, forced to look out for myself, I stayed in the Capital."30 Whitman's note to himself remarked upon Doyle's "experience in the war—prison—escaping" (NUPM, 2: 821). It's been assumed that Doyle was a prisoner of war. The story I have been able to reconstruct, based on material in the National Archives, suggests a different scenario. Apparently, after Doyle was released from the hospital in Petersburg, he decided against resuming life in the Confederate Army. Instead, he `escaped' to the North. As he attempted to cross Federal lines, Doyle was captured by Union forces and taken to Washington, DC.31 On April 18, 1863, he was confined in Carroll Prison, an annex to the Old Capitol Prison.32

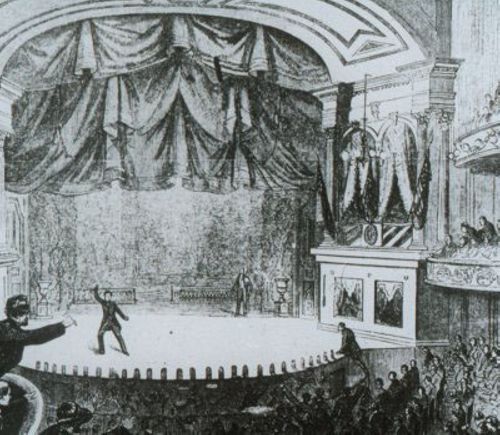

Figure 2.

Peter Doyle was imprisoned in the Old Capital complex from April 8 to May 11, 1863.

Figure 2.

Peter Doyle was imprisoned in the Old Capital complex from April 8 to May 11, 1863. Doyle was charged with "entering & attempting to enter our lines, from the insurgent states, without a permit from the Federal authorities." In response to the charge, Doyle asserted that he was a British subject, and a refugee from war-torn Virginia. Notice of Peter Doyle's imprisonment was made in Washington's Evening Star on Monday, April 20. The following day, Doyle's sister-in-law Ellen (nee Branzell) Doyle and Skip Branzell, visited Pete at the Old Capitol. Ellen Doyle may have appealed to the British legation to secure Peter's release. On May 2, Secretary of State William Henry Seward requested information about Doyle's case, on behalf of the British minister, Lord Lyons. Army Judge Advocate Levi C. Turner investigated the case. His report concluded that Doyle, and several other prisoners confined with him, were "poor Irishmen who fled from Richmond to avoid starvation . . . They will not take oath of allegiance, but will give sworn parole." On May 11, Peter Doyle was released, after taking an oath not to aid the Rebellion.

The Doyles in Washington

Apparently, Peter Doyle's first job in D.C. was as a Smith's helper, at the Washington Navy Yard. A Peter Doyle is listed on the Yard's monthly payroll report from December 1863 until June 1865.33 During Confederate General Jubal Early's raid on Washington in July 1864, the 1,000 Navy Yard employees were organized into an ad-hoc militia to join in the defense of the Capital City.34 Whether Pete himself took arms against his former comrades in the Rebel army is unknown. At the Yard, Pete's daily wages increased from $1.50 per day at the beginning of the period to $2.25 per day at the end of the period. A James Doyle (Pete's brother?) was also employed as a Smith's helper from February 1864 through February 1865 (nine days in the latter).

Initially, Pete lived with his brother, Francis Michael, and Francis' wife, Eleanor (or Ellen). Francis was nearly ten years older than Peter. Standing 5 feet 7 inches tall, Francis had gray eyes, brown hair, and a fair complexion, with a roguish scar on his left cheek.35 Unlike the rest of the Doyles, Francis never lived in Virginia. He had settled immediately in D.C. Francis married Eleanor Branzell, a Maryland native, on October 16, 1858. Reverend L.F. Morgan, a minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church, performed the marriage in Washington, DC.36 Like his father, Francis was a blacksmith. He worked at the Washington Navy Yard in the late 1850's and early 1860's.37

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Francis had enlisted in Captain Robert Clarke's Company, of the D.C. Military Infantry.38 He joined the Union forces on April 24, 1861—just one day before his brother Peter enlisted as a Confederate soldier in Virginia. Francis served his full three-month term of enlistment. He was mustered out on July 24, 1861. Francis and Eleanor had a daughter Emma, born on July 31, 1864. Francis again joined the military in the War's closing months, enlisting on March 2, 1865, in the U.S. Navy. He served as a fireman aboard the Wasp until his discharge on April 18, 1867. After his military service ended, Francis joined the Metropolitan Police force, on February 15, 1868. He and his wife, Eleanor, had two more children: Mary born on June 12, 1868, and Robert Emmet (named after the Irish patriot), born on February 24, 1871. The children were brought up in their mother's church.

In addition to Peter and the Francis Doyles, the house at 62 M Street, South (which would have been situated between 4th and 5th Streets, SW in today's grid) also was home to brother, James Doyle, and Robert Branzell, who I assume was Eleanor's brother.39 James Doyle married in 1866.40 His wife, Charlotte, gave birth that same year to a boy, James, and to a daughter, Kate, in 1869.

Their mother, Catherine, and younger siblings, Edward and Margaret eventually joined the Doyle brothers, in Washington. It remains unclear what happened to Peter's father. According to Whitman, Peter, Sr. went to New York in search of work, "and that was the last that was heard of him. No doubt he was drowned or killed" (Johnston & Wallace, 147–148).41 The 1870 Population Census for the District of Columbia lists Pete, Jr. as the sole breadwinner and head of the household, which included his mother (listed as a widow), and Edward, and Margaret.42

The Doyle households were within blocks of one another in the city's Southwest section. Surrounded by the Potomac River, the Eastern Branch (now called the Anacostia) River, and the City Canal connecting the two, this area was popularly called "the Island," and was home to a large community of European immigrants and newly freed slaves.

Pete's uncle and aunt, Michael and Ann Nash, lived in a large, brick house they owned at 813 L Street, SE, a few blocks from the Navy Yard. They had two sons, Edward, a bricklayer, and William, a carpenter. Born in Limerick, Ireland on May 1, 1805, Michael Nash came to this country about 1818. He lived the remainder of his life in the District of Columbia.43 As a young man, he was a member of the local militia and the volunteer fire department. Later, he was employed as superintendent of the shoemaking establishment connected with the old penitentiary. In time, he was a charter member and large stockholder of the Firemen's Insurance Company, and was also a stockholder in the Great Falls Ice Company.

Nash was married to Ann Maria Clarke who was born on June 10, 1810, to Robert and Jane Clarke.44 Michael Nash owned two houses in addition to the one he lived in, and several other pieces of property in the District.45 Nash was a member of the Association of the Oldest Inhabitants of the District of Columbia. This citizens group was founded in 1865 to "keep alive the reminiscences of the past and the social and paternal communion of the present."46 Its membership included such prominent Washingtonians as banker and philanthropist, William Wilson Corcoran, and Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, an owner of The Willard Hotel. An annual tradition in which Nash took part was the New Year's Day call upon the President at the White House.47

The Nashes were communicants at St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church on Capitol Hill. Michael Nash may have been responsible for introducing Whitman to the parish's pastor, Reverend F.E. Boyle, to whom Whitman sent greetings in a letter to Doyle (Corr.., 2: 113).

Clang, Clang, Clang...

Evidently while still working at the Navy Yard, 48 Peter Doyle began a second-job as a horsecar conductor with the Washington and Georgetown Railroad Company. This company began operation on May 17, 1862, with a Congressional charter. The first route, along Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol to the Treasury, opened two months later. The three-mile journey cost a nickel and took 45 minutes. Service on the route was every five minutes. Eventually, the line was extended westward along Pennsylvania Avenue past Washington Circle, and into Georgetown. It ended at Bridge and High Streets (Wisconsin Avenue and M Streets, North West, in today's grid). Eastward, the line went along Pennsylvania Avenue, headed south on Eighth Street, SE, passed the Marine Barracks, and ended up at the Navy Yard at M Street, SE. A line running north along Fourteenth Street, NW, from Pennsylvania Avenue to Boundary Street (now Florida Avenue), and one running the length of Seventh Street, NW, from the Potomac River to Boundary Street, were later added.49 The original 10-horsecar operation grew to one with 60 cars—running 941 trips daily—that carried over eight and a half million passengers in 1865.50

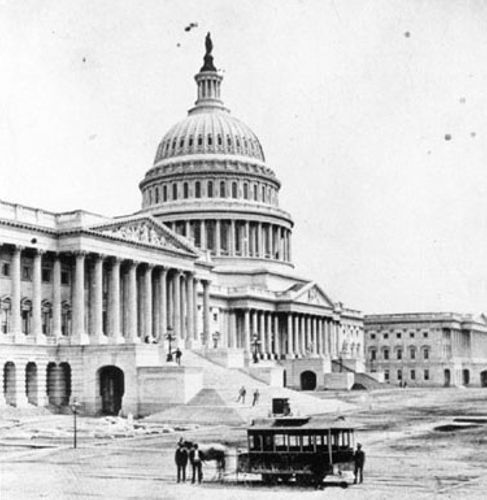

Figure 3.

Peter Doyle worked as a conductor on the Washington and Georgetown Railroad Company horsecars shown here in front of the U.S. Capitol.

Figure 3.

Peter Doyle worked as a conductor on the Washington and Georgetown Railroad Company horsecars shown here in front of the U.S. Capitol. The earliest cars consisted of a single-truck coach that measured fifteen by seven feet (Boettjer, 23). Passengers entered through the rear. The coach sat twenty persons on two silk velvet benches running along the sides of the car. The window panes were of stained and plain glass. The windows were covered with poplar blinds, and damask curtains. An oil lamp, covered by a red-tinted glass globe, which hung in the center of the car, lighted the car's interior. The railroad also had open-air cars for summer use, with cross-wise seats that accommodated twenty-four riders.

You ask where I first met him? It is a curious story. We felt to each other at once. I was a conductor. The night was very stormy,—he had been over to see Burroughs before he came down to take the car—the storm was awful. Walt had his blanket—it was thrown round his shoulders—he seemed like an old sea-captain. He was the only passenger, it was a lonely night, so I thought I would go in and talk with him. Something in me made me do it and something in him drew me that way. He used to say there was something in me had the same effect on him. Anyway, I went into the car. We were familiar at once—I put my hand on his knee—we understood. He did not get out at the end of the trip—in fact went all the way back with me. I think the year of this was 1866. From that time on we were the biggest sort of friends (Bucke, 23).

Although Doyle dated the meeting to 1866, he and Whitman probably met in early 1865. It seems likely that the encounter Doyle described occurred between January 23, and mid-March. The former date was when Whitman returned to DC from his six-month hiatus in Brooklyn (Corr.., 1: 248), and the latter date was when Whitman left Washington again to visit his family in New York (Corr.., 1: 255–256). (Whitman didn't return until after Lincoln's assassination in April). This dating coincides with the fall-off in hours worked by Doyle at the Navy Yard in February 1865. This, in turn, suggests the approximate time that Doyle began his second job as a streetcar conductor. Doyle's reminiscence of their first meeting indicated a cold climate.

That Whitman and Doyle knew one another before the end of the Civil War is attested by two separate published remembrances. John Burroughs situated Doyle and Whitman on the streetcars together "toward the close of the war."51 (The last of the Confederate armies surrendered in June of 1865.) The writer Joel Sayre recalled that his father had encountered Whitman and Doyle together during Whitman's tenure at the Office of Indian Affairs.52 (Whitman worked at there from January through June 1865.)

Whitman provided additional evidence of their meeting in 1865. In a Specimen Days entry dated "December 1865", Whitman suggested that he and Doyle were by then well-acquainted. Whitman also dated a photograph of himself and Doyle as taken in 1865. The attraction between Walt and Pete seems to confirm the cliché about opposites attracting. Physically, the six-foot tall, heavy-set, middle-aged Whitman towered over the young, five-foot eight Doyle. Intellectually, Whitman was highly literate, both as a reader and a published author. In contrast, Doyle possessed only a rudimentary education (albeit a "Jesuit education," at St. Mary's Sunday school). Whitman identified strongly with the Union as a native-born Easterner. Doyle, of course, was born in Ireland, and raised in America's South; his first independent adult act was to fight against the Union.

In other respects, Whitman and Doyle were cut from the same cloth. Despite his white-collar occupations of journalist and government clerk, Whitman was at heart "one of the roughs." He felt most at home with the workingman that Doyle represented. For a time, Whitman had even taken up the carpenter's craft that his father had taught to Walt and the other Whitman boys. Whitman's brother, Andrew, worked in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, just as Doyle worked at its Washington counterpart. Whitman could identify with Doyle's emotional and financial responsibilities to a widowed mother and dependent siblings. Whitman was shouldering similar obligations himself. It is likely that Doyle's large, extended family served as a surrogate to Whitman's geographically distant own.

Peter Doyle was described, by his niece, Mary Catherine, to her daughter Mary, as "a homosexual."53 This capacity in Doyle—"to love as I myself am capable of loving," as Whitman put it in his "Calamus" poem—cemented the bond between the two men. For the next eight years (until Whitman's stroke in 1873 caused his removal to Camden, New Jersey), Walt and Pete were constant companions.

Doyle bore some similarity to Fred Vaughan. This is the man whom Charley Shively has speculated was Whitman's lover during the late 1850's, when Whitman was writing his "Calamus" poems.54 Both Doyle and Vaughan were ethnic Irish; foreign-born (Vaughan was a native Canadian); railroad men (Vaughan was a Broadway stage coach driver, and later a railroad engineer); and in their early twenties, at the time of each man's involvement with Whitman.55

Poet's Muse

I heard that the President and his wife would be present and made up my mind to go. There was a great crowd in the building. I got into the second gallery. There was nothing extraordinary in the performance. I saw everything on the stage and was in a good position to see the President's box. I heard the pistol shot. I had no idea what it was, what it meant—it was sort of muffled. I really knew nothing of what had occurred until Mrs. Lincoln leaned out of the box and cried, "The President is shot!" I needn't tell you what I felt then, or saw. It is all put down in Walt's piece—that piece is exactly right. I saw Booth on the cushion of the box, saw him jump over, saw him catch his foot, which turned, saw him fall on the stage. He got up on his feet, cried out something which I could not hear for the hub-hub and disappeared. I suppose I lingered almost the last person. A soldier came into the gallery, saw me still there, called to me: "Get out of here! we're going to burn this damned building down!" I said: "If that is so I'll get out!" (Bucke, 25–26).Doyle claimed that Whitman later made use of Pete's eyewitness account for the poet's Lincoln sketches (in Memoranda During the War, Specimen Days, and various lectures). It is interesting to speculate in what other ways Doyle may have influenced Whitman's work. Was Pete the muse for Whitman's most popular Lincoln tribute, the poem, "O Captain! My Captain!"? Recall that the poem presents Lincoln as a ship's master, who dies just as the craft he piloted safely through a storm arrives at harbor. In developing this poem, Whitman may have sought to impress Doyle, by making the Irish immigrant's own sea journey to America the central image of this heroic elegy to Lincoln ("The heavy storm and danger Good Friday night...almost a wreck," is how Whitman recalled Doyle's voyage). Both the president's assassination and Doyle's near wreck at sea occurred on a Good Friday. Whitman may also have broken from his own poetical tradition and adopted rhyme to make the poem more appealing to the limerick-spouting Doyle. 56 Interestingly, Whitman's first draft of "O Captain!" is not rhymed, but rather written in free verse. 57 The captain of the poem may have been drawn from Doyle's description of Charles Theobald, the master of the immigrant ship that brought the Doyle family to this country. Or, it may have been drawn from Doyle's image of Whitman as an "old sea-captain" riding the horsecars. This of course presupposes that Doyle had described his voyage to Whitman by the time the poem was written; Whitman's notation about Doyle's voyage to America apparently was not made until 1875 (NUPM, 2: 821).

Figure 4.

Peter Doyle witnessed the assassination of President Lincoln from his seat in the theater's balcony.

Figure 4.

Peter Doyle witnessed the assassination of President Lincoln from his seat in the theater's balcony. While "O Captain!" is remarkable for its use of rhyme, a second poem written at this time, "Come Up From The Fields Father," is unique in its use of a first name to identify the poem's fictional hero. The name used is "Pete." 58 Other than this one instance, Whitman never before or after in his poems used a personal name for a fictional character.59

The real life hero of this poem, however, was not Peter Doyle. Likely, it was Oscar Cunningham, the Ohio soldier whom Whitman nursed at Armory Square Hospital. The young soldier died in 1864, and was buried on the grounds of Arlington Plantation, the home of Colonel Robert E. Lee's wife, Mary Custis Lee (what is now Arlington National Cemetery). In particular, the poem takes place on an Ohio farm. A friend in the hospital writing to the boy's sister, just as Whitman wrote to Helen Cunningham, transmits the news of the son's illness. The letter-writer is ultimately mistaken about the son's condition, just as Whitman failed to communicate in time Oscar's imminent death to the Cunningham family. Whitman's decision to use the name, "Pete," reflects an aesthetic decision. The first name of his new buddy strikes the required note of familiarity that the formal-sounding "Oscar" does not. It also suggests transference to Doyle of the powerful emotions Whitman had felt towards the convalescing soldiers.

The "Calamus" emotions are expressed throughout the Drum Taps poems. If Doyle did not directly inspire these poems, he at least reinforced the feelings underlying them, as Whitman was preparing the war poems for publication. This sentiment is seen especially in the following sample: "Vigil Strange I Kept On The Field One Night" and its depiction of the older soldier burying his "son of responding kisses, (never again on earth responding;)" (LG Var., 2: 491);the rover of "As Toilsome I Wander'd Virginia's Woods" who comes upon the unknown soldier's grave with its rude inscription, "Bold, cautious, true, and my loving comrade." (LG Var., 2: 509); "The Dresser"'s bitter-sweet remembrance that "(Many a soldier's loving arms about this neck have cross'd and rested, Many a soldier's kiss dwells on these bearded lips.)" (LG Var., 2:482); the loving gaze of "O Tan-Faced Prairie-Boy," which was valued in camp "more than all the gifts of the world," (LG Var., 2: 507); "Reconciliation" with the dead enemy, "I draw near, I bend down and touch lightly with my lips the white face in the coffin." (LG Var., 2: 556); and the poet's confession made "As I Lay With My Head In Your Lap Camerado" that, "I confront peace, security, and all the settled laws, to unsettle them;" (LG Var., 2: 549).

Whitman made a gift of the Drum Taps manuscript to Pete (Bucke, 30). Perhaps this was Whitman's way of acknowledging the young man's creative influence on the poet during this fruitful period.

The effects of his friendship with Doyle may also be seen in the 1867 edition of Whitman's Leaves of Grass. Whitman added several new poems, but more significantly, deleted three poems that had been in the "Calamus" section. As Florence Freedman noted in her biography of Whitman's knight-errant, William Douglas O'Connor, Whitman eliminated those poems that "expressed self-doubt and despair," but "kept those which expressed love and longing unaccompanied by despair."60 The excised poems were: "Long I Thought That Knowledge Alone Would Suffice," in which the poet renounces his vocation because "One who loves me is jealous of me, and withdraws me from all but love," (LG Var., 2: 379); "Hours Continuing Long," in which Whitman writes, "Hours discouraged, distracted—for the one I cannot content myself without, soon I saw him content himself without me;" (LG Var., 2: 379); and "Who Is Now Reading This?" which has Whitman confessing to have "interior in myself, the stuff of wrongdoing," (LG Var., 2: 386).

Freedman credits Whitman's more optimistic mood to "his finally having found `lovers and avowers' of himself and of his poems in William and Nelly O'Connor, in Charles Eldridge, John Burroughs, and in the Washington circle of friends—with William as the central figure" (Freedman, 199–200). Freedman's focus was limited to the smart literary set, and did not include the unlettered Doyle. It seems likely, however, that Walt's new-found confidence in love was, in large measure, a result of his satisfying friendship with Pete. The excisions can be interpreted as Whitman putting the unhappiness of his first "Calamus" love relationship with Fred Vaughan behind him, as he embarked on this new love adventure.

Loving Comrades

It was one of my diversions to ride on the front platform with the driver in all kinds of weather except during thunderstorms. One of my occasional companions in that enjoyment on the cars of the Washington and Georgetown Railroad Company was the poet Walt Whitman, who preferred to ride on the front platform of a car on which a young man with light curly hair, whose name I think was Doyle, and whose appearance indicated Irish descent, was conductor. Whitman's custom was to get on the car of this conductor at the Treasury Department, where he was employed, after office hours, and ride toward the Navy Yard. During the rides with them in which I participated, their conversation, so far as I can remember, consisted of less than fifty words. It was the most taciturn mutual admiration society I ever attended; perhaps because the young Apollo was generally as uninformed as he was handsome, and Whitman's intellectual altitude was too far beyond his understanding to be reached by his apprehension or expressed by his vocabulary. The fellowship was a typical manifestation of the unconscious deference which mediocrity pays to genius, and of the restfulness which genius sometimes finds in the companionship of an opposite type of mentality. The youthful grace of the conductor and the mature personality of the poet with iron-gray beard, slouch hat and rolling shirt collar that exposed a sturdy throat and enough of a broad chest to move with envy the modest young women of this day who affect the low-necked exposure, completed an ideal study in individual physical contrast.61

Doyle recalled that he and Walt would watch from the streetcar, as President Grant strolled from the White House to visit Mrs. Magruder, widow of a well-respected local physician. Doyle also provided a rare glimpse of Whitman's anger in a streetcar incident. Whitman had rubbed up against "an old fellow (a fellow who was trying to represent the state of Virginia in the Senate)." The passenger cursed Walt, Walt issued an epithet in return, and the two came close to blows before Pete pulled them apart. 62 Perhaps Walt's antagonist was Alexander Sharpe of Richmond, whom the Conservative/Democratic caucus in the Virginia Legislature unsuccessfully put up against the Unionist candidate John Lewis, in the 1869 Senate campaign race.

Doyle recalled, "It was our practice to go to a hotel on Washington Avenue after I was done with my car. I remember the place well—there on the corner. Like as not I would go to sleep—lay my head on my hands on the table. Walt would sit there, wait, watch, keep me undisturbed—would wake me up when the hour of closing came" (Bucke, 24-25). Doyle's recollection is strikingly reminiscent of Whitman's "Calamus" poem, "A Glimpse:"

The bar that the two patronized was in Georgetown's Union Hotel, at the corner of Washington and Bridge Streets (30th and M Streets, NW, in today's grid).63 During the first two years of the Civil War, the hotel had been used as a hospital for patients with contagious diseases. In the winter of 1862-63, Louisa May Alcott nursed the wounded soldiers there and drew her Hospital Sketches from the experience.64

Figure 5.

Pete and Walt patronized the Union Hotel, near the Georgetown terminus of Doyle's horsecar route.

Figure 5.

Pete and Walt patronized the Union Hotel, near the Georgetown terminus of Doyle's horsecar route. Unlike the physical wreck of his last years, Whitman was, by Doyle's recollection, "an athlete—great, great. I knew him to do wonderful lifting, running, walking." (Bucke, 23.) Walt and Pete were especially fond of taking long hikes together out of the city. A favorite destination of the wanderers was Doyle's American hometown of Alexandria, Virginia. The two would cross over the Potomac River's Eastern Branch via the Navy Yard Bridge, wander south along the Maryland side of the river, and take the ferry across to Virginia. Then, the rovers headed back home, following the Potomac on the Virginia side. Crossing the Long Bridge into the District's Island neighborhood, Whitman saw Pete to his home.

Doyle recalled that Walt was "always whistling or singing. We would talk of ordinary matters. He would recite poetry, especially Shakespeare—he would hum airs or shout in the woods" (Bucke, 26). Whitman told Horace Traubel, "We would walk together for miles and miles, never sated. Often we would go on for some time without a word, then talk—Pete a rod ahead or I a rod ahead...It was a great, a precious, a memorable experience. To get the ensemble of Leaves of Grass you have got to include such things as these—the walks, Pete's friendship: yes, such things: they are absolutely necessary to the completion of the story."65

Their jaunts would occasionally be interrupted. A shout from behind of, "After all not to create only!" would signal the arrival of Ohio Congressman James Garfield. The former Brigadier General in the Union Army was a good friend of Walt's, despite his persistent ribbing about the poor reception accorded Whitman's 1871, address to the American Institute (Bucke, 32).

I remember one special night. We met a half-loaded fellow with some of his friends, George Alfred Townsend, `Gath' he is now called, & some other newspaper boys. George was officiously familiar with Walt—insisted on introducing his friends, & all that & Walt held him off—froze him out—would not be introduced. It was impossible for Townsend to make his point. Now, Walt was always dignified—simple enough, too—& this was a sample of the manner he showed to all alike—famous or plain folks—who stepped across what he thought his private border-line.66

Whitman's love for the photographer's lens is well known. On at least two occasions, he brought Pete along with him for a sitting. In the better-known picture, the two are seated facing each other, each with a silly grin. Whitman once asked Thomas Harned (his future literary executor) what the poet's look suggested. Harned offered, "Fondness, and Doyle should be a girl" (Traubel, 3: 543).

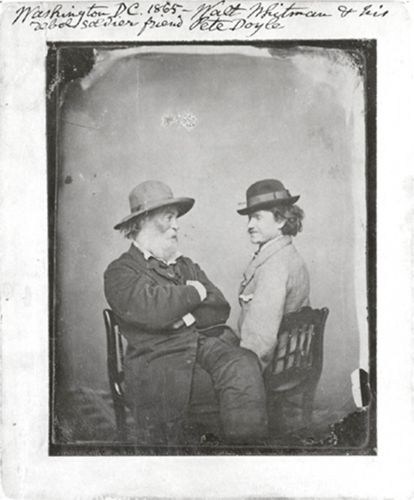

Figure 6.

Walt's fondness for Pete is captured in this photograph.

Figure 6.

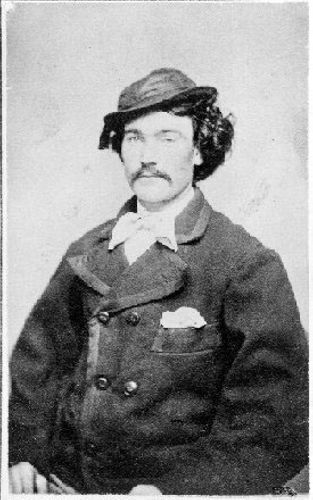

Walt's fondness for Pete is captured in this photograph. In a more serious pose, Whitman is seated looking over at Doyle, who faces the camera squarely as he stands by the older man's side. More flattering to Pete's good looks than either of the photographs with Whitman is a solo portrait taken on July 5, 1868.67 67 The photographer captured Doyle's handsome, moon-shaped faced, with the wispy mustache drooping over full lips, a sharp gaze in his right eye, and a lazy, withdrawn look in the left, and a head of thick, curly hair, barely contained by a rakish leather cap. All three photographs were taken in the studio of Moses P. Rice, located on Pennsylvania Avenue, between 2nd and 3rd Streets, NW.

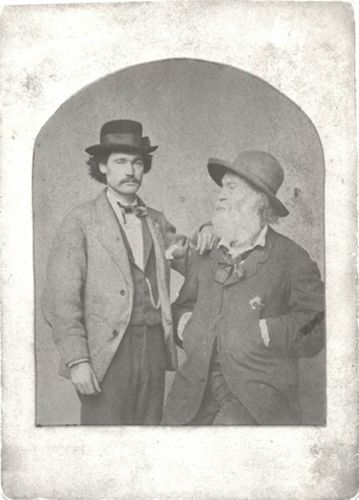

Figure 7.

Doyle and Whitman, circa 1869.

Figure 7.

Doyle and Whitman, circa 1869.  Figure 8.

Doyle's Irish good looks are on full display in this Moses P. Rice studio photograph.

Figure 8.

Doyle's Irish good looks are on full display in this Moses P. Rice studio photograph. "Dear Pete,": The Correspondence

Although Whitman and Doyle's friendship dates to early 1865, the first extant correspondence between them is in the fall of 1868. At the time, Whitman was in New York visiting family and friends. The very first surviving letter of what was to prove a long correspondence was from Pete, written on September 18.68 He exclaimed, "I could not resist the inclination to write to you this morning it seems more than a week since i saw you" (Shively, 104). On September 25, Walt declared, "I think of you very often, dearest comrade, & with more calmness than when I was there—I find it first rate to think of you, Pete, & to know that you are there, all right, & that I shall return, & we will be together again. I don't know what I should do if I hadn't you to think of & look forward to" (Corr.., 2: 47). In the six weeks that they were apart, Doyle wrote at least seven times, and Walt wrote eleven times (Corr.., 2:67).

Doyle's letters to Walt were full of the small events of daily life that Whitman so loved to hear. `Pete the Great' (as he signed himself) described his trip to the baseball game where he saw the Olympics clobber Cincinnati. He visited the theater to see the Black Crook—"i had no idea that it was so good. Some of the scenes was magnificent" (Shively, 106). He shared with Walt the gossip about the Railroad men—"Jim Sorrill sends his love & says Charley's baby is well and doing first rate...I would like to send you a Picture of Dave as i write this, he is about two thirds asleep in one end of the car while i sit in the other end writing this letter" (Shively, 108). Pete sent on the Washington papers, including an article in the September 18, Daily Morning Chronicle about Whitman's visit to Brooklyn. He also sent him the September 30, Evening Star, which contained an account of Chicago written by Whitman's friend and the Star's editor, Crosby Stuart Noyes: "Mr. Noyes...was on my car ...& he looks first rate i told him i sent you the star containing his letter and it seemed to please him very much" (Shively, 107–108).

On his side, Whitman recounted the sights, sounds and smells of the East River, a Democratic Party torch light parade, and his publishing endeavors (Corr., 2: 55–56). Whitman told Doyle of his side trip to Providence, Rhode Island. There he was the guest in the home of Dr. William Francis Channing and his wife, Jeannie, (Ellen O'Connor's sister). He also stayed with former Congressman Thomas Davis. Satisfied with his comfortable arrangements, Walt crowed, "So you see, Pete, your old man is in clover" (Corr.., 2: 60). Whitman remarked at the abundance of fresh fruits and flowers at his host's home: "Pete, I could now send you a bouquet every morning, far better than I used to, of much choicer flowers" (Corr.., 2: 61).

You would be astonished, my son, to see the brass & coolness, & the capacity of flirtation & carrying on with the girls—I would never have believed it of myself...Of course, young man, you understand, it is all on the square. My going in amounts to just talking & joking & having a devil of a jolly time, carrying on—that's all...So long, dear Pete—& my love to you as always, always (Corr.., 2: 62-63).

Pete's last letter to Whitman that Fall, sent October 14, mentioned attending the wake for a cousin who had died. Perhaps this was Robert E. Taylor, who the Evening Star for Saturday, October 10, mentions had died that day, "aged 31 years, 5 months, and 6 days." According to the paper, Taylor was waked at the residence of Pete's uncle, Michael Nash, on October 12. After sending love from "all the boys," Doyle signed the letter, "Pete X X" (Shively, 109).

My darling, if you are not well when I come back I will get a good room or two in some quiet place, (or out of Washington, perhaps in Baltimore,) and we will live together, & devote ourselves altogether to the job of curing you, & rooting the cursed thing out entirely, & making you stronger & healthier than ever. I have had this in my mind before, but never broached it to you. I could go on with my work in the Attorney General's office just the same—& we would see that your mother should have a small sum every week to keep the pot a-boiling at home...Dear comrade, I think of you very often. My love for you is indestructible (Corr.., 2: 84–85).

DR. JOHNSTON HAS DISCOVERED THE most Certain, Speedy, and only Effectual Remedy in the World for Weakness in the Back or Limbs, Strictures, Affection of the Kidneys and Bladder, Involuntary Discharges, Impotency, General Debility, Nervousness, Dyspepsia, Languor, Low Spirits, Confusion of Ideas, Palpitation of the Heart, Timidity, Trembling, Dimness of Sight or Giddiness, Disease of the Head, Throat, Nose, or Skin, Affections of the Liver, Lungs, Stomach, or Bowels—those terrible Disorders arising from Solitary Habits of Youth—SECRET and solitary practices more fatal to their victims than the song of Syrens to the Mariners of Ulysses, blighting their most brilliant hopes or anticipations, rendering marriage, &c. impossible.

YOUNG MEN especially, who have become the victims of Solitary Vice, that dreadful and destructive habit which annually sweeps to an untimely grave thousands of young men of the most exalted talents and brilliant intellect, who might otherwise have entranced listening Senators with the thunders of eloquence, or waked to ecstacy the living lyre, may call with full confidence. 69

The Lock Hospital did sufficiently good business hawking cures for sexual malady that it could afford to run a full-column advertisement several days a week, for months at a time.

From Walt's letters to Pete that summer, it appears that Doyle soon shook his moroseness about his own health. Whitman himself wasn't well that summer, but he minimized his illness to keep Pete from worrying about him. Whitman mentioned that his "particular women friends" had sent for him, although he had not been to see them (Corr.., 2: 87). Walt did find the time to ride the East River ferries: "Some of the pilots are dear personal friends of mine—some, when we meet, we kiss each other (I am an exception to all their customs with others)" (Corr.., 2:88).

References in the 1868 and 1869 correspondence by both Doyle and Whitman to the latter's capacity for flirting with women are curious, given the assumption that Whitman and Doyle were "lovers" in the contemporary sense of the word. It seems especially odd that Whitman mentioned his relationships with women to Doyle, only to quickly discount the seriousness of these encounters. This may simply have been Whitman's way of reassuring Doyle of the poet's "manliness" (and by extension, Doyle's own), given the heterosexual norms of the day. Another possibility is that Whitman had occasional involvement with women while in New York and at home in Washington. In such a case, Whitman may have felt the need to assure Doyle that, despite these "secondary" relationships, his affection for Pete was "primary." In this respect, although Doyle in his published remarks to Bucke and Traubel claimed that Whitman had no special relationships with women in Washington, privately Doyle told Laurens Maynard (the publisher of the "Calamus" letters from Whitman to Doyle) that "he knew of a woman in Washington with whom W. had sex relations."70 If such woman existed, she has yet to be identified.

Adhesiveness

He [Walt] was a long time after me to go to New York, while his mother was alive. I asked him: "Will we stop there with your mother?" He was a little doubtful about that. We both stayed in Jersey City. 72 The Whitmans lived on Portland Avenue. We took our dinner with Mrs. Whitman. We would take a bus-ride in the morning—then go to Brooklyn and have dinner. After we had had our dinner she would always say—"Now take a long walk to aid digestion." Mrs. Whitman was a lovely woman. There were just the three of us eating together. Walt and I had a week of it there in New York that time. It was always impressed upon my mind—the opera he took me to see—"Polyato." All the omnibus drivers knew him. We always climbed up to the top of the busses, our heels hanging over (Bucke, 27).

The opera they saw was Gaetano Donizetti's Poliuto. This story about the life of the Armenian Christian martyr was performed on May 26, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. The tenor C. Lefranc performed the title role. The American-born soprano Clara Kellogg played his wife Paolina (Odell, 8: 669).

In Walt Whitman & Opera, Robert D. Faner noted that Whitman refers to Poliuto by name both in Specimen Days and in the poem, "Italian Music in Dakota."73 In the latter, Whitman enthuses over, "Thy ecstatic chorus Poliuto." Whitman may have been as moved by Donizetti's tribulations in putting on this opera as he was by the martyrdom of Poliuto and Paolina depicted therein. Originally written to be performed in Naples in 1838, the opera was stopped by the town censors, who believed the subject matter too sacred to be paraded on the stage.

From Doyle's much-later perspective, the trip was idyllic. However, Walt's single letter to William O'Connor from Brooklyn spoke not of pleasure, but of pain (from the bad hand): "It has caused me much suffering, since I have been here," he wrote (Corr.., 2: 98–99). Walt told William that he saw Mrs. Whitman, but he made no mention of Pete's presence.

TO GIVE UP ABSOLUTELY & for good, from the present hour, this FEVERISH, FLUCTUATING, useless UNDIGNIFIED PURSUIT of 16.4—too long, (much too long) persevered in,—so humiliating——It must come at last & had better come now—(It cannot possibly be a success) LET THERE FROM THIS HOUR BE NO FALTERING, NO GETTING at all henceforth, (NOT ONCE, UNDER any circumstances)—avoid seeing her, or meeting her, or any talk or explanations—or ANY MEETING WHATEVER, FROM THIS HOUR FORTH, FOR LIFE (NUPM, 2: 888–889)

Oscar Cargill first surmised that 16.4 stood for Peter Doyle (the alphabetical order of his initials). Roger Asselineau followed this up with the observation that the "im" of him had been erased and replaced by "er" to form her (NUPM, 2: 885). Whitman faults himself for making inappropriate puns, plays upon words, and sarcastic comments to "16" (NUPM, 2: 887). One can imagine that the contrariness Whitman exhibited during political and philosophical discussions with O'Connor, and which led eventually to their falling-out, was present also in Whitman's relationship with Doyle. Perhaps less able than O'Connor to parry with Whitman, Doyle may have had a lower tolerance for the older man's occasionally caustic bantering.

Whitman urged himself: Depress the adhesive nature/ It is in excess—making life a torment/ Ah this diseased, feverish disproportionate adhesiveness/ Remember Fred Vaughan (NUPM, 2: 889-890)

Whitman's trip to Brooklyn in the late spring of 1870 with Doyle, his second "Calamus" lover resurrected memories of his first lover, Vaughan. An important motif of the "Calamus" poems written about the Vaughan relationship, is a preoccupation with unrequited love. (This can be seen particularly by examining Whitman's original "Live Oak" manuscript, from which the "Calamus" poems sprung.)74 The summer of 1870 manuscript shows that Whitman had likewise become preoccupied that Doyle did not eturn his love. The MS chastised, "Cheating, childish abandonment of myself, fancying what does not really exist in another, but is all the time in myself alone—utterly deluded & cheated by myself, & my own weakness—REMEMBER WHERE I AM MOST WEAK, & most lacking. Yet always preserve a kind spirit & demeanor to 16. BUT PURSUE HER NO MORE." (NUPM, 2: 887).

As already noted Whitman's initial response to his friendship with Doyle had been to purge the "Calamus" cluster of those poems that expressed his abandonment fears. What caused these fears to arise anew? One possibility is that a change may have occurred in Whitman's physical relationship with Doyle. The 1869 correspondence suggested that Doyle was not immune to popular sexual bugaboos. As a result, Doyle may have been frightened into a period of abstinence. In the 1870 MS, Whitman sounded like a frustrated suitor, lamenting that his "useless, undignified pursuit" of Doyle had continued far too long.

Perhaps Doyle was undergoing a period of soul-searching about his future. One can imagine that Doyle, at 27-years old, was subject to considerable societal pressure to marry. This may be what is meant by the comment made by Edward "Ned" Stewart, who in a February 25, 1870, letter to Whitman noted that Pete "is coming to his senses and thinking about settling down in life and is going to benefit by the numerous opportunities which he has" (Shively, 111). `Settling down' is typically used to convey an intention to marry. Although Shively suggests that Stewart himself was seemingly attracted to men, he also was pursuing a woman in Vancouver at the time of his letter writing to Whitman and Doyle (Shively, 111–112). Whitman described Doyle to Traubel as "a little too fond maybe of his beer, now and then, and of the women: maybe, maybe" (Traubel, 1: 542–543). Whitman's first lover, Vaughan, eventually married (after his relationship with Walt had ended).

The trip to Mrs. Whitman's home with Pete, and the reminders of his shared Brooklyn home with Vaughan (Shively, 50), may have exacerbated Whitman's own desire, expressed to Doyle the previous summer, to settle down with Pete. Stewart's comments provided the reason why this dream was unattainable, when he asked Walt, "How does he [Pete] & the widow pull together now, I suppose Ile find you & Pete in the same box when I return to Washington" (Shively, 111). Doyle, of course, was unable to establish a home with Walt, because Pete's mother continued to rely upon her son for financial support.

Whatever the reason for Whitman's crisis of faith in his relationship with Doyle, it resolved itself. As Whitman was preparing to leave for New York that summer, Doyle acknowledged to Walt how deeply attached he was to him. From Brooklyn, Whitman wrote to Doyle on Saturday, July 30, "We parted there, you know, at the corner of 7th st. Tuesday night. Pete, there was something in that hour from 10 to 11 o,clock (parting though it was) that has left me pleasure & comfort for good—I never dreamed that you made so much of having me with you, nor that you could feel so downcast at losing me. I foolishly thought it was all on the other side. But all I will say further on the subject is, I now see clearly, that was all wrong" (Corr.., 2: 101). A few days later, Whitman again recalled this leave-taking, describing their parting hour as if it were the scene lifted from his 1865 poem, "When I Heard the Learn'd Astronomer:"Dear son, I can almost see you drowsing & nodding since last Sunday, going home late—especially as we wait there at 7th st. and I am telling you something deep about the heavenly bodies—& in the midst of it I look around & find you fast asleep, & your head on my shoulder like a chunk of wood—an awful compliment to my lecturing powers (Corr.., 2: 103–104).

Whitman remained in Brooklyn through mid-October. For the rest of his vacation, Walt's correspondence with Pete focused on mundane affairs. Pete griped regularly about his job on the streetcars. After violating some work rule, he was suspended. Walt condemned the "thin-livered cuss" Silvanus Riker, president of the Washington and Georgetown Railroad, for his ill treatment of Doyle. "Let Riker go to hell," Walt advised Pete (Corr.., 2:106). The older man proposed to take Pete's mind off of his troubles: "All I have to say is—to say nothing—only a good smacking kiss, & many of them—& taking in return many, many, many, from my dear son—good loving ones too—which will do more credit to his lips than growling & complaining at his father" (Corr.., 2: 110). Walt mentioned dining with an old acquaintance, now grown rich, who lived in "a big house on Fifth avenue—I was there to dinner (dinner at 8 p.m.!)—every thing in the loudest sort of style...But my friend is just one of the manliest, jovialest best sort of fellows—no airs—& just the one to suit you & me—no women in the house—he is single" (Corr.., 2: 109).

Assured now of Pete's affection, Whitman disregarded his resolution to shun sarcasm in his dealings with Doyle. He needled the Catholic Doyle about the Papal States' absorption by Garibaldi in the nascent Italy: "I propose to take my first drink with you when I return, in celebrations of the pegging out of the Pope & all his gang of Cardinals & priests—& the entry of Victor Emanuel into Rome, & making it the capital of the great independent Italian nation" (Corr.., 2: 112). Whitman asked Pete to convey his love to a long list of friends, including Aunt and Uncle Nash, and Father Boyle of St. Peter's Catholic Church (Corr.., 2: 113). Aside from a single reference to his "being quite a lady's man again in my old days" after accompanying a young female neighbor to New York (Corr.., 2: 102), Whitman, from this time on, no longer made the suggestive references about flirting with women that had been present in the earlier years' correspondence to Doyle. Whitman wrote to William O'Connor, asking him to secure lodging for Walt at the Union Hotel, where Walt and Pete hung out after Doyle's workday (Corr.., 2: 115). The hotel was full, and Whitman took a room upon his return at the St. Cloud, on the corner of 9th and F Streets, NW (Corr.., 2: 116).

The reconciliation with Doyle did not include a fulfillment of Whitman's wish to share a home with Pete. Throughout their long friendship in Washington, the two men kept separate quarters. Whitman lived in various rooming houses within easy commute of the Treasury Building (15th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, Northwest), while Doyle provided a home for his mother and younger siblings on M Street, Southwest, between 4 1/2 and 6th Streets.

Figure 9.

Whitman had an office in the southwest wing of the Treasury Building, across from his Fifteenth Street boarding house, shown in the background.

Figure 9.

Whitman had an office in the southwest wing of the Treasury Building, across from his Fifteenth Street boarding house, shown in the background. Walt Defends Big Brother

In the spring of 1871, Whitman joined the Doyle family as it rallied around its eldest son, patrolman Francis Michael. His arrest and incarceration on May 12 of a young boy for stealing eggs was sensationalized in the D.C. press, as an egregious instance of police brutality.75 Most of the local press was not satisfied with Doyle's reprimand by the Police Board, and demanded his removal from the force. Pained at the public humiliation of Peter Doyle's eldest brother, Whitman drafted an editorial in Francis Doyle's defense. Whitman commended Doyle as "an energetic officer...[who] bears an excellent repu[ta]tion, and served the Union cause, as soldier or sailor, all through the war" (NUPM, 2: 783). He lambasted the press for its "attempt to make martyrs and heroes of the steadily increasing swarms of juvenile thieves & vagabonds who infest the streets of Washington." Although this editorial was not published, Whitman's behind-the-scenes lobbying apparently kept editors Crosby Noyes of the Evening Star and D.C. Forney of the Sunday Morning Chronicle—the District's two largest circulation newspapers—from excoriating Doyle in print. Eventually, the other newspapers lost interest in the story. Francis Doyle kept his job on the police force.

There was quite a brush in N.Y. on Wednesday—the Irish lower orders (Catholic) had determined that the Orange parade (protestant) should be put down..I saw a big squad of prisoners carried along under guard—they reminded me of the squads of rebel prisoners brought in Washington, six years ago—The N.Y. police looked & behaved splendidly—no fuss, few words, but action—great, brown, bearded, able, American looking fellows, (Irish stock, though, many of them)" (Corr.., 2: 126–127).The old man softened this jab with an affectionate sign-off, "Love to you, my dearest boy," (Corr.., 2: 127).

Later that year, Pete and his family were shocked by the murder of Francis Michael Doyle. On the afternoon of December 29, 1871, Policeman Doyle was attempting to serve a warrant to search the house of John and Maria Shea, who were fences for stolen goods. Mrs. Shea shot him in the chest with a Remington-type six-shooter, killing the policeman immediately. Whitman attended the funeral for Francis, held on New Year's Eve (Corr.., 2: 148–149). According to the report in the Evening Star, thirty of Doyle's fellow officers escorted the policeman's remains to a grave in Washington's Congressional Cemetery.

Figure 10.

Peter Doyle is buried with his brother Edward in Washington's Congressional Cemetery.

Figure 10.

Peter Doyle is buried with his brother Edward in Washington's Congressional Cemetery. Working on the Railroad

Doyle left his job as streetcar conductor the following year. He "went on the Pennsylvania Railroad" in 1872 (Bucke, 23). The Pennsylvania Railroad, through its Baltimore and Potomac Railroad subsidiary, opened its line from Baltimore to Washington, D.C., on July 2, 1872.76 Doyle started on the railroad as a brakeman, according to the occupational listing for Doyle in the 1873 Washington city directory.

In the days before the widespread use of automatic air brakes, a train necessarily was braked by hand.77 The brakeman rode on the top of the freight or passenger car where he could observe the terrain and quickly respond to the need for putting on, or releasing, the brakes. He did this by turning a wheel on the roof, which was connected to a rod that, in turn, applied friction to the train's wheels. Each car had its own brake, and a brakeman was responsible for braking several cars in a long train. To do this, the brakeman had to jump across and run the length of each of several cars to apply the brakes in good time. In bad weather anytime, but especially during the cold winters when the roofs were covered with snow and ice, this job could be quite dangerous. A mis-step might easily result in a brakeman's falling off the train, or between the cars. Another feature of the brakeman's job was "going back to flag." When a train was stopped on the tracks, the brakeman on the rear car had to take his red flag or lantern and go back down the track a half-mile or more to give the "stop" signal to the engineer of any train that may be following. In performing this job, the brakeman faced the risks of over-exposure in frigid temperatures, and being hit by a train that failed to heed his stop signal.

A brakeman was also responsible for "coupling," that is, joining together, the separate cars of a train, before it set out on its assigned run. Coupling required the brakeman to lift the link in one car and guide it into the opening of the approaching car. Although railroad regulations specified that the brakeman stand beside the tracks and perform the task by the use of a short stick, more typically the brakeman chose to couple the cars by hand as he stood on the tracks in between the cars. This exposed him to the risk of having his hands or entire body crushed by the approaching car should he make the slightest mistake in the task's execution.

Given such risks faced by a railroad man of that day, it is no wonder that Whitman described Doyle's work, in a letter to Ellen O'Connor, as "his dangerous post on the Baltimore & Potomac RR" (Corr.., 2: 230).

Nursing Walt

Pete do you remember...during my tedious sickness and first paralysis ('73) how you used to come to my solitary garret room and make up my bed, and enliven me and chat for an hour or so—or perhaps go out and get the medicines Dr. Drinkard had order'd for me—before you went on duty? (Bucke, iii)

Whitman's mother wrote approvingly to Walt of Pete's ministrations on her son's behalf: "i thought of peter. i knew if it was in his power to be with you he would and cherefully doo everything that he could for you" (Corr.., 1: 193n). By mid February, Walt was making short jaunts outside his room, "convoyed" as he put it, by Pete or Eldridge. Pete gave Whitman a shillelagh to lean upon as he walked (Traubel, 5: 228).

In February, Whitman received the sad news that his brother Jeff's wife, Mattie, had died. Towards the end of March, Whitman resumed work at the office. He took the pre-caution, however, of writing a will, on May 15, 1873 (NUPM, 2: 917–919). He left most of his estate to his mother, in trust for the care of his feeble-minded brother, Edward. Token sums were also given to his surviving sisters, and brothers. Peter Doyle was the only non-family member listed in the will. Walt wrote, "I wish Eighty-Nine Dollars paid to Peter Doyle—that sum being due to him from me. I also will to him my silver watch. Appleton-Tracy movement, hunting-case. I wish it given to him with my love."

That spring, Walt had begun to receive disturbing reports of his mother's ill health. He visited her in Camden, New Jersey, where she was then living with her son, George, and his wife. He arrived in time to be present at her death, on May 23. Walt returned to Washington on June 2, staying at the home of Mr. and Mrs. J. Hubley Ashton (one of the Attorneys General whom Whitman served under) at 12th and K Streets, NW (Corr.., 2: 222). Whitman did not stay long with his Washington friends. Within two weeks, he had moved in with George in Camden to convalesce, hoping the move would be temporary.

I rec'd your letter telling me you was too late to get any chance for the letter carrier's position—& about Mr. Noyes' friendliness—Are things just the same, as far as you and your crew are concerned? I think about you every night—I reproach myself, that I did not fly around when I was well, & in Washington, to find some better employment for you—now I am here, crippled, laid up for God knows how long, unable to help myself, or my dear boy—I do not miss any thing of Washington here, but your visits—if I could only have a daily visit here, just as I had there. (Corr.., 2: 227)