Wednesday, October 17, 1888.

Wednesday, October 17, 1888.

7:45, evening. W. reading Memoirs of Bewick. "It is autobiographical," said W: "simple, plain, interesting." "Are you particularly interested in artists? You read a lot about Blake, Millet—". He replied: "I suppose I am, but not necessarily. The book just accidentally turned up—I have had it for years: so I tackle it again. Why do I read? Here I sit, all day long, days in and out: what else have I to do?" He handed me a copy of Alden's Literature: "Kennedy sent it on in a bundle: I took it up—saw that piece on Thackeray by Guernsey—started it—read the whole thing." "Did it seem to be of any special value?" "No—not that: I got started: kept on because I got started. I must fill up the time in some way: it's greatly a matter of chance what I read: a book may turn up, like the Bewick—a long, long time mislaid: then I am at it again. My reading is wholly without plan: the first thing at hand, that is the thing I take up." Had he finished the Mrs. Carlyle letters? "Yes—and for good: done with them: there isn't the slightest possibility of a revival of interest: take them away for forever." Picked up the Bewick again: "I like the make of the book—the open page: it is all leaded out—has a liberal look. Every book ought to be leaded, double-leaded, triple-leaded: we ought to have respect for each others' eyes: though sometimes a fellow has so much to put into a book he has to forego his esthetics very largely." Again he said: "I read by fits and starts—fragments: read in moods: no sequence, no order, no nothing." Had he seen the Critic piece talked of the other day? "Yes, at last: I read it, not carefully, but clearly enough to give me its main notions. I think people [Begin page 493] generally attach more importance to that sort of writing than I do." Asked me: "have you met Gosse?" No. "Well—if Gosse did not mention me it must have been by order." "Whose order?" "Metcalf's: You know about Metcalf? He was at one time on the North American Review—left there, I don't know whether voluntarily or by Rice's command, going I don't know for what: started his rival affair." "But why do you suppose Metcalf objects to you?" "I can say I am certain of it: Metcalf has no time for me: has always been of that feeling—was so when on the Review." "You never had anything in the Forum?" "No—never: would not send them anything."

We are expecting Bucke's visit. W. expressed interest in Bucke's report. "He always sends it on. Of course that drink argument this year won't hit me—I care nothing for it. I am more interested in the patients—their number, their work, all that. You remember, I have been up there—I know the lay of the ground." Speaks of "the gloomy news all around"—explaining: "There's poor O'Connor—I get to thinking of him days at a time: his condition is miserable—dangerous: I look ahead with fear: and there's my sister up in Vermont—she's having hell's own time, between her viper husband and a thumb she lost years ago which is now troubling her again." Asked him about the autographs: "I haven't signed any for two or three days but I'll get at it tomorrow or next day and finish the job." Then said: "I've about decided to have one hundred of the books made up at once." Asked him if he had any visitors today. "Yes—one of the right sort: Frank Williams: he was over. He stayed with me but a few minutes but they have lasted for hours. Horace—you fellows mustn't make any mistake about Frank: he's one of the saints of the calendar." No sign of the Linton cut. I wrote to Arthur Stedman today. I had a postal from Burroughs this morning:

West Park, Oct. 16, 1888.I hope you will continue writing me such notes as these, "My food nourishes me better." I shall certainly see our great friend [Begin page 494] again. I am pretty well—work now with better heart. I had a few days by the sea with Mr. Johnson after I left Camden. My love to W.W.

J. B.W. asked: "Is the postmark West Park? I don't know why, but West Park and West Farms always mix themselves together in my mind. I know nobody at West Farms: the name simply got into my noddle in some inexplicable way. How queer it is with the mind: it gets a false impression—then there's an end: can never wholly eject the interloper." Turning again to Burroughs: "If you write to him give him my love: that will be all for this time. I do not remember writing the line John quotes, though I have no doubt I did write it. I have written him I think twice since my sickness set in: if I did write that I don't know what called it forth." W. called my attention to a copy of the Yonkers Gazette containing two sonnets (marked with blue pencil) by W. L. Shoemaker: September Sonnets: The Valley Pathway Blue. W. spoke of S.: "he was here a week ago: came up : I liked him: an old man—rather past the age of vigor—but discreet, quiet, not obtrusive." Then added: "Take the paper: give the sonnets more careful reading: they are not bad—good, rather: I was attracted. He sent me the paper after he had gone home."

Brown thinks they are making a new plate for the title. W. says: "Maybe I've put my foot in it: maybe I'd better kept my mouth shut." Osler said to me: "Carpe diem should be his motto." I had not repeated this to W., who today said to me: "Carpe diem is my motto." I told him I had sold another book. Laid the money on the table. "Don't let it get lost," I said. He laughed: "Never fear. I lose other things but I never lose money." He went searching among his papers on a chair near by, finally producing a letter and handing it to me: "It's from Jerome Buck, lawyer and so forth: warm, warm: he got the book. Now he writes to say how-do-you-do and here's luck! Read the letter: it's quite after your own heart. Tom [Begin page 495] tells me Buck is a clever lawyer." W. then asked: "What did you make out of William's letter—the one I gave you yesterday? It was written in one of his most vehement moods. William's enemies always felt that an earthquake had occurred after he had blown one of his lambasting blasts. Have you got the letter in your pocket there?" He had seen me make a motion as though to get it. "Good! Good! read it to me: I want to hear it again." He fixed himself in the chair as if to enjoy himself and I read. He repeatedly broke in with, "Good!" "That's every word true!" "That's right, give 'em hell!" "Now, William, don't be too hard on 'em!" "Chadwick! heaven help 'im!" and several other exclamations which I do not recall.

Washington, D. C. Aug. 19, 1882. Dear Walt:I got your card of the 6th, and duly the new edition of the book arrived, for which I am much obliged. I have now all the editions, except the second, which I hope to possess some day. The weather has been until yesterday so fearfully oppressive that I have unwittingly delayed acknowledging the book, having been almost sick with the heat. I sent a blast against Comstock to the Tribune on Friday, apropos of his threats in that paper of the 6th, which I suppose you saw. They may not print it or they may tomorrow. Whitelaw Reid being away is against me. We shall see. The article is brief, but a scorcher. I debated before sending it, holding your interests in consideration, but concluded that Comstock means mischief, and thought prudent to make him feel the talon as a warning. If he meddles with your book in New York, I will do my utmost in all directions to have him removed from his Post Office agency, and I think I can raise a tempest that will darken him forever, if I try.

It is splendid, the way the Rees Welsh edition sells. I am delighted.

Much obliged for your interest about the Florio Montaigne. I only asked because I saw Welsh dealt in old books. There has been a boom in Montaigne in late years, and it is not so easy [Begin page 496] to get hold of the earlier editions now. I have been re-reading him lately. It is immense. I can hardly doubt that Bacon is the true author—the book so fits into his scheme. That chapter, On Some Verses in Virgil, is tremendous, and backs you greatly.

I thought Gilder of the Critic was a friend of yours. His taking up for that miserable Chadwick against me, misrepresenting and falsifying my argumentation, was anything but friendly. The Index did a rascally thing lately in reprinting Chadwick's letter verbatim, without my reply. Dr. Channing went up to Boston and saw Underwood, the editor, and gave him a piece of his mind (the Doctor thinks it "a crushing reply.") Underwood excused himself for not printing my answer on the ground that it was too personal! When you remember how Chadwick assailed me as a liar, you will appreciate this delicious reason. Upon hearing of it, I wrote Underwood a note in which I gave him cantharides, or, as the Long Island boys say, "hell under the shirt." To which he rejoined in a whining letter saying he meant to do me no injustice, and would print a reply from me to Chadwick if I would write him one and make it short! In conclusion he begged me to remember that his paper was "small." To which I had a mind to answer, "Very." But I have not again written him, being quite satisfied with letting him know what I thought of his fair play.

Dr. Bucke has written me about his book. Can anything be done to make Rees Welsh publish it? I wish it could be done. Now is the time, when public interest has been awakened, and persecution is yet possible.

That is a sick article of Gordon's you sent me. But will have something to say on that point yet.

I have a card from John Burroughs on his return.

I was sorry to see the item in the Tribune of the 15th, saying that your book had been proscribed by Trinity College, Dublin, through the efforts of one Galbraith, described as a Fellow of the College, and a damned low fellow too, I should say. The news made me fear the possible effect here. Strange that I

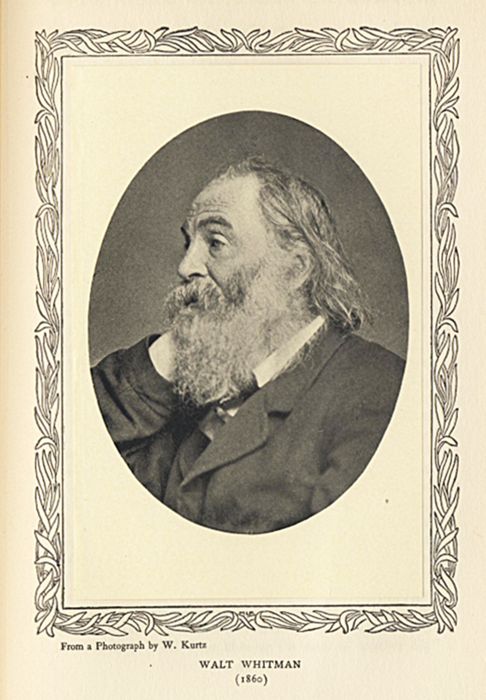

[Begin page figure-014]

[Begin page 497] cannot find the alleged letter to Marston in any of the Boston papers. It was in Dublin, either at this College or the University, that Tyrrell lectured on you, glorifying the book they now proscribe. "So runs the world away."

[Begin page 497] cannot find the alleged letter to Marston in any of the Boston papers. It was in Dublin, either at this College or the University, that Tyrrell lectured on you, glorifying the book they now proscribe. "So runs the world away."

Good-bye. I hope to hear that the third edition is already called for!

Faithfully, W. D. O'Connor.W. said: "Looked back upon from these days of peace that sounds like the report of a commander in chief off the field of battle. William was always in the thick of danger: was always the first in and the last out of a fight."