With Walt Whitman in Camden (vol. 3)

VOLUME THREE [Begin page ii]

Copyright 1914 by Horace Traubel

Copyright 1912 by The Century Company

Copyright 1912 by Mitchell Kennerley

The Plimpton Press - Norwood - Mass - USA

ILLUSTRATIONS CONTAINED IN THIS VOLUME

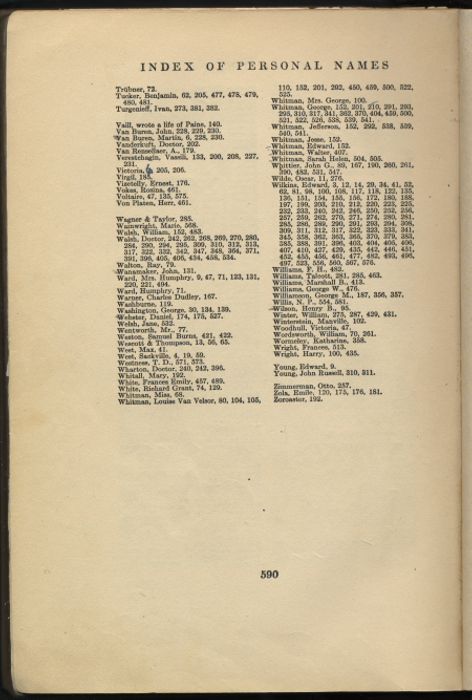

| Morse's Plaster Model of Walt Whitman in a Rocking Chair | Frontispiece |

| Facing page | |

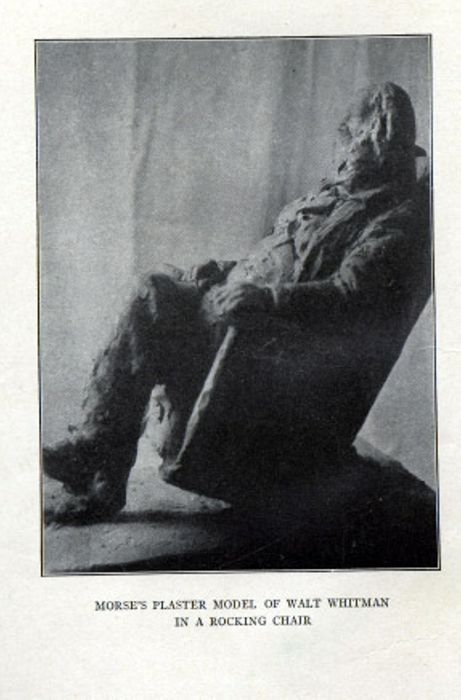

| Walt Whitman's "copy" and Instructions to the Printer for the Printing of Labels for "Complete Poems and Prose" | 188 |

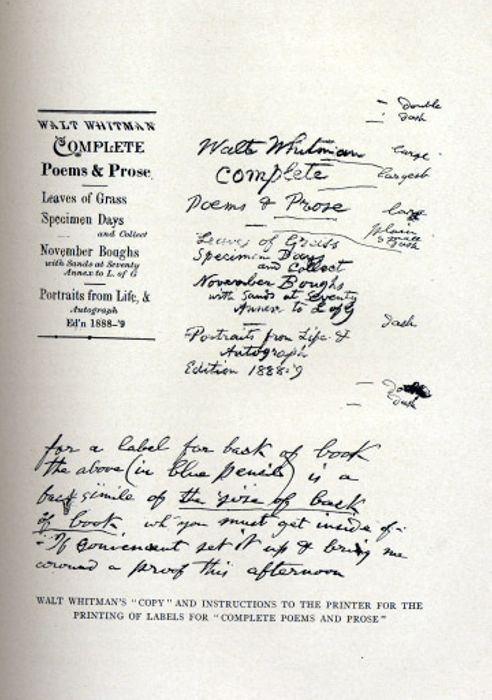

| Four Page Letter from Walt Whitman to William O'Connor September 28, 1869 | 236 |

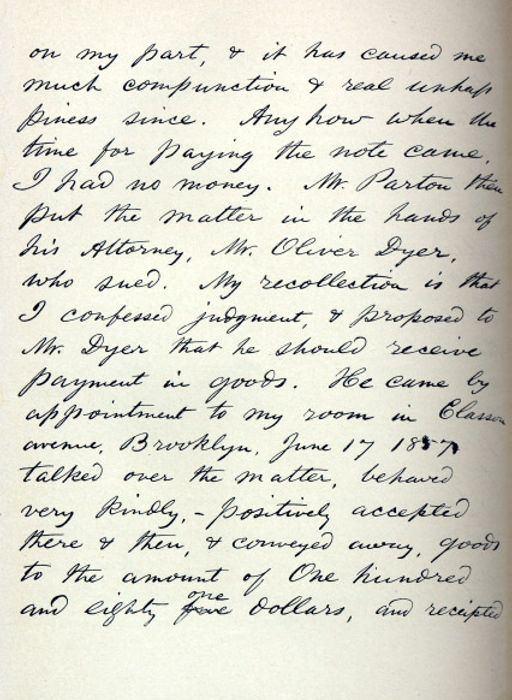

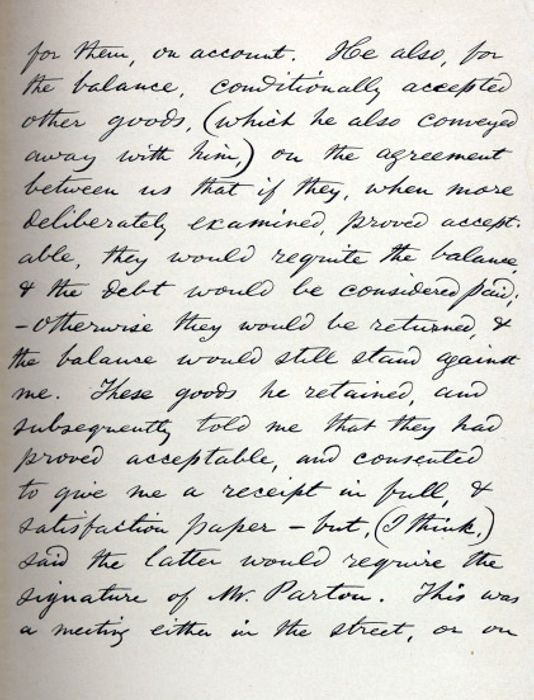

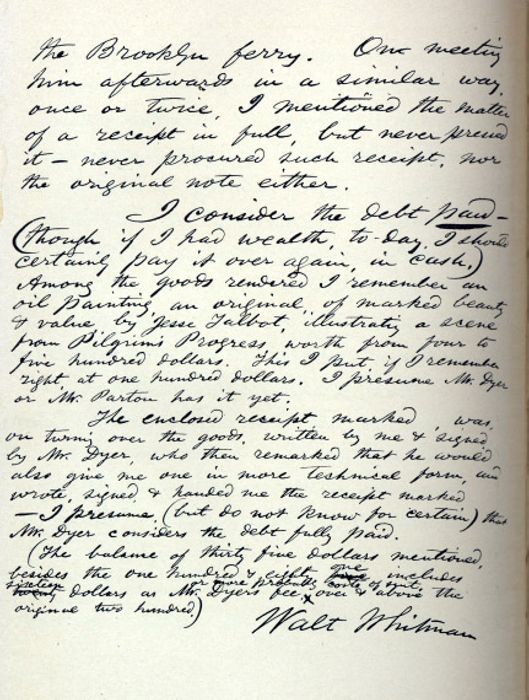

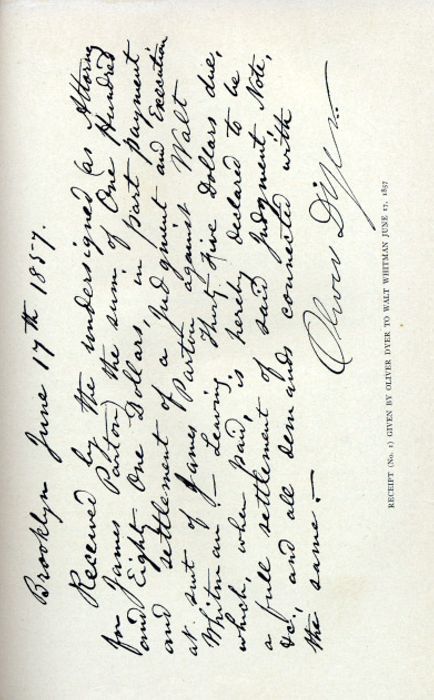

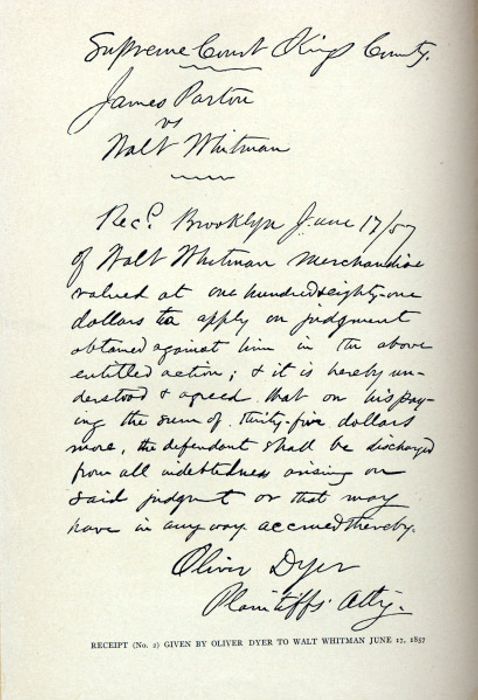

| Receipt (No. 1) Given by Oliver Dyer to Walt Whitman June 17, 1857 | 238 |

| Receipt (No. 2) Given by Oliver Dyer to Walt Whitman June 17, 1857 | 239 |

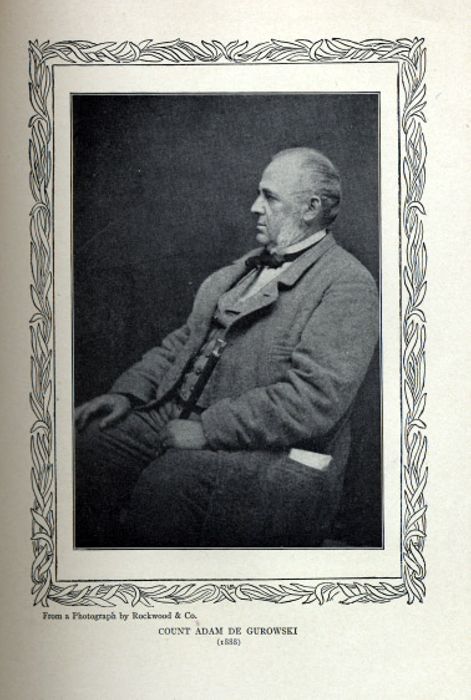

| Count Adam de Gurowski | 340 |

| From a photograph by Rockwood & Co., 1888 | |

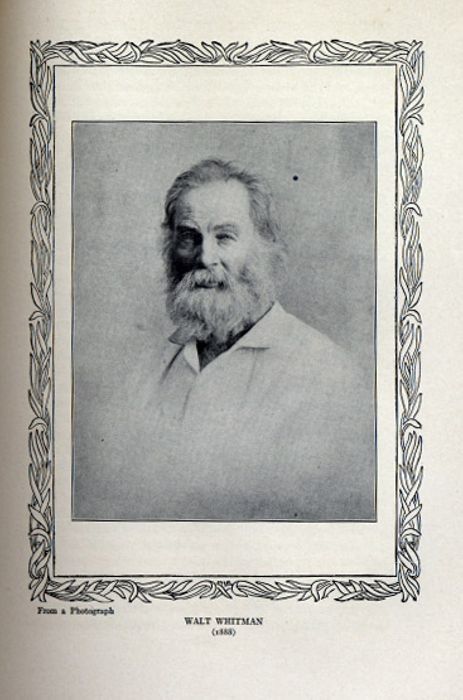

| Walt Whitman From a photograph, 1888 | 364 |

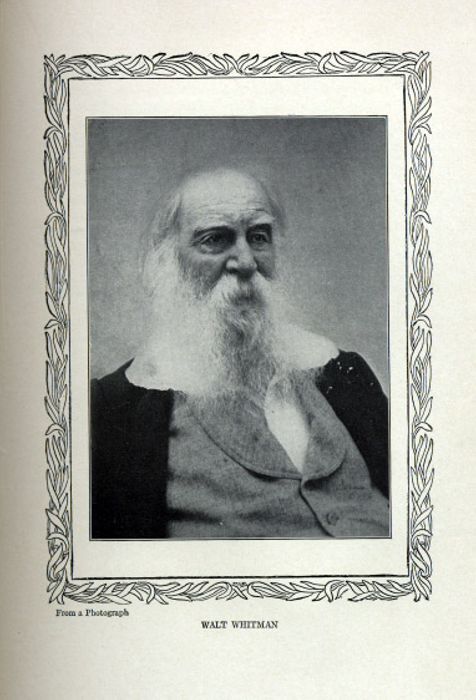

| Walt Whitman From a photograph | 378 |

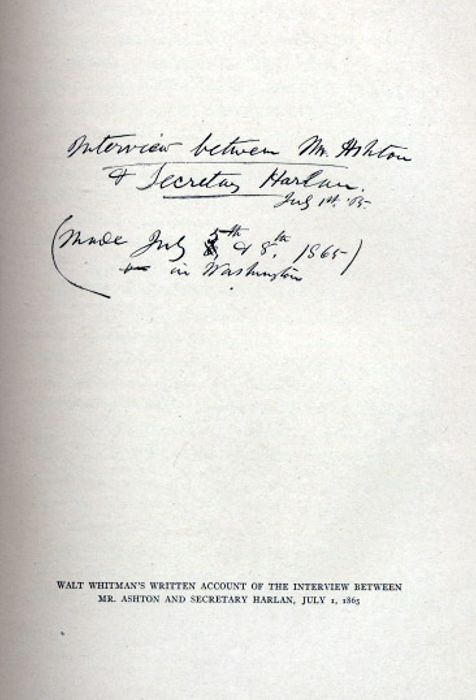

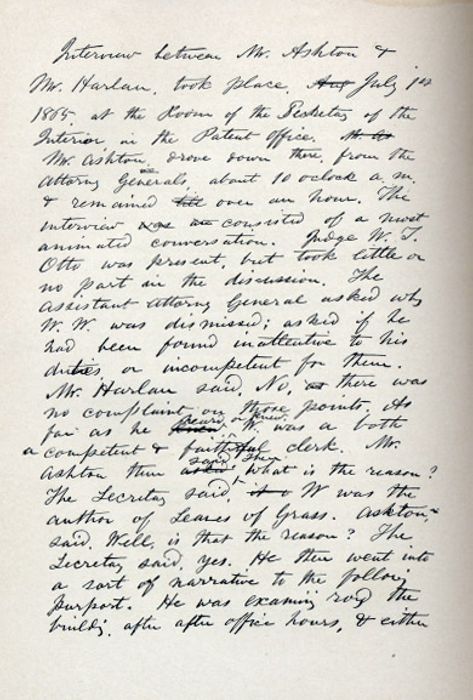

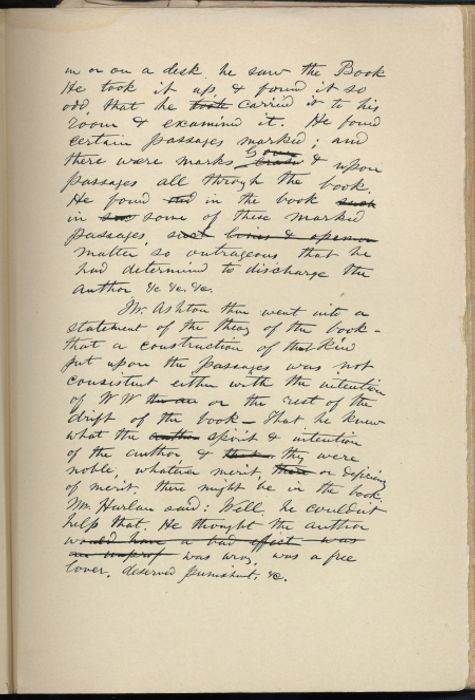

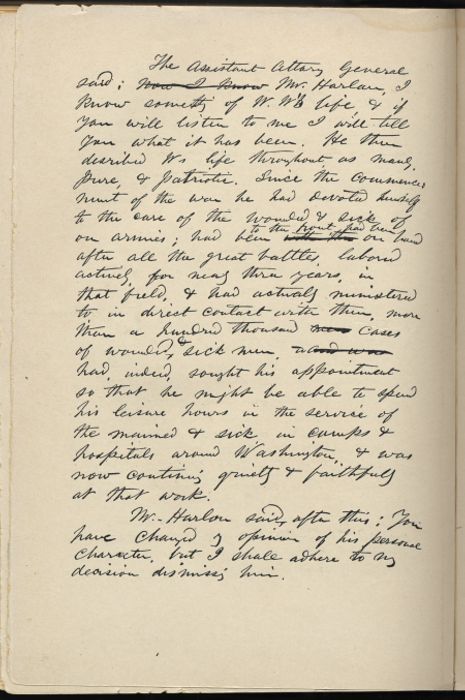

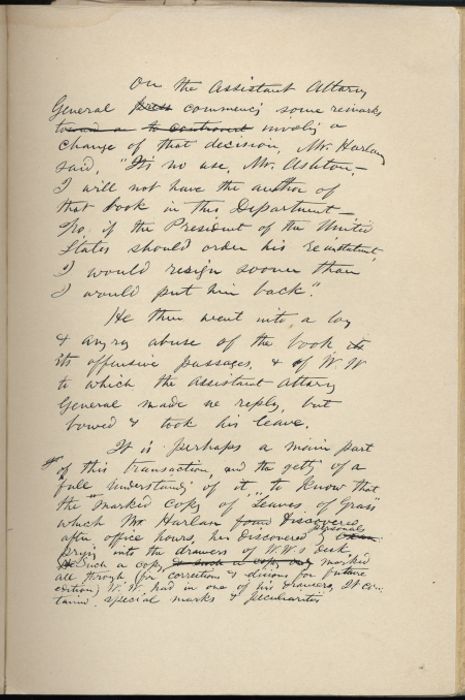

| Walt Whitman's written account of the interview between Mr. Ashton and Secretary Harlan | 472 |

| July 1, 1865 | |

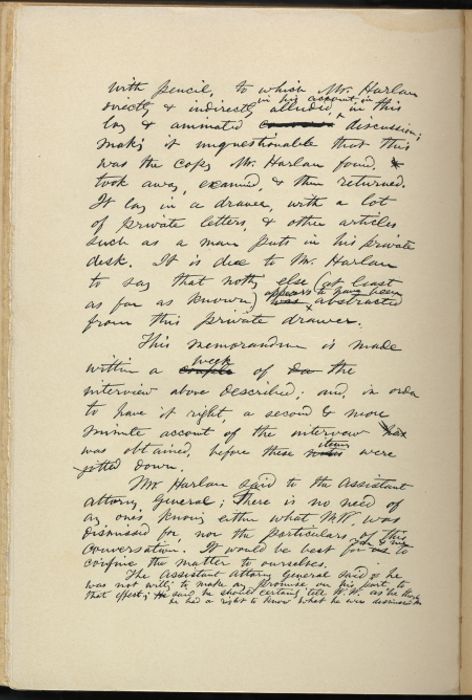

| Walt Whitman From a photograph, 1873 | 494 |

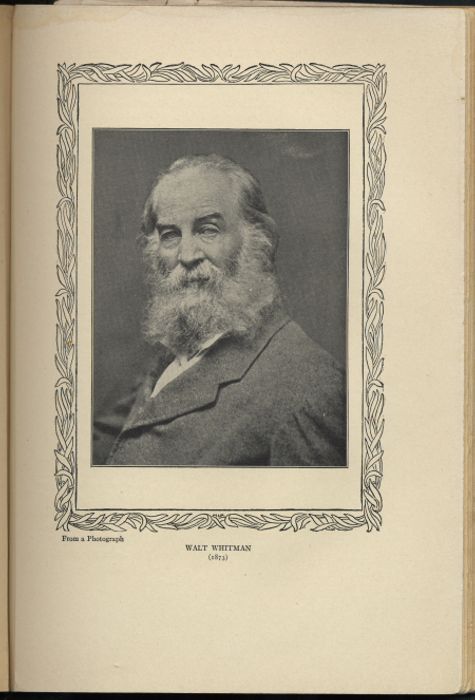

| Walt Whitman and His Rebel Soldier Friend, Pete Doyle, 1889 | 544 |

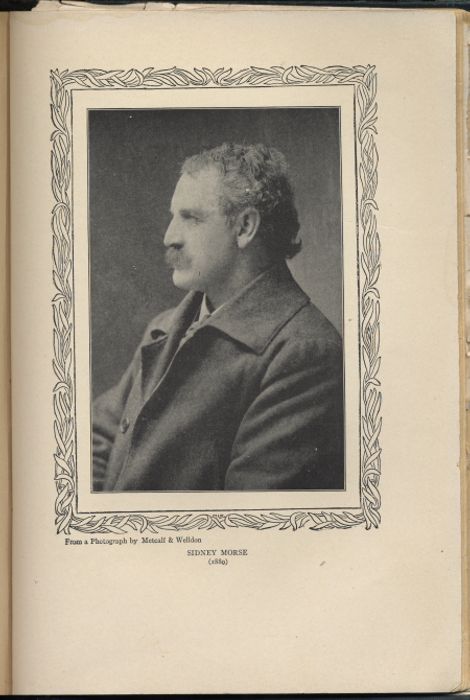

| Sidney Morse | 554 |

| From a photograph by Metcalf & Welldon, 1889 | |

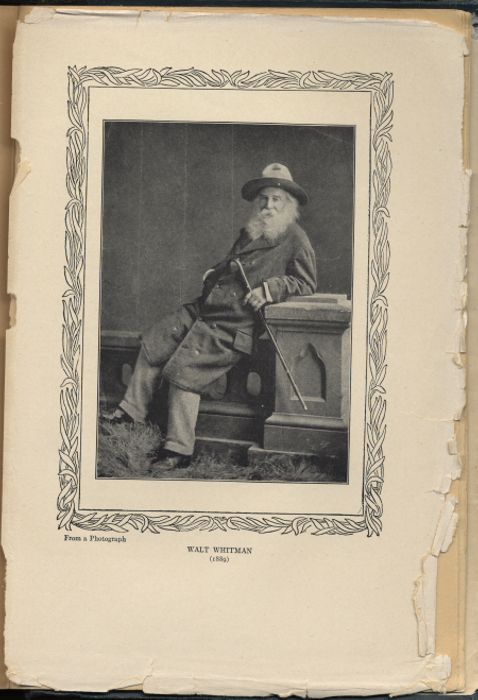

| Walt Whitman From a photograph, 1889 | 574 |

LETTERS CONTAINED IN THIS VOLUME

(INCLUDING OTHER MANUSCRIPTS OF WALT WHITMAN)

| Alden, William L., 259 |

| Alcott, A. Bronson, 243, 245 |

| Binckley, John M., 475 |

| Blake, J. V., 153 |

| Blauvelt, William H., 8 |

| Bucke, Richard Maurice, 248, 269, 397 |

| Bullard, Laura Curtis, 556 |

| Burroughs, John, 28, 260, 281, 350 |

| Carpenter, Edward, 192, 414 |

| Conway, Moncure D., 111, 267, 296, 322 |

| Cook, William, 202 |

| Croly, D. S., 560 |

| Dowden, Edward, 41, 146, 215 |

| Dyer, Oliver, 238, 239 |

| Eldridge, Charles, 483 |

| Freyer, Samuel S., 577 |

| Gardner, Alexander, 346 |

| Garland, Hamlin, 67, 114 |

| Gilder, Joseph B., 124 |

| Gillette, F. B., 465 |

| Greg, Thomas Tylston, 432 |

| Hale, Philip, 533 |

| Harlan, James, 471 |

| Hay, John, 91 |

| Hine, Mrs. Charles, 330 |

| Houghton, Lord (Richard Monckton Milnes), 31 |

| [Begin page viii] Johnson, John H., 331 |

| Knortz, Karl, 488 |

| Miller, Joaquin, 225 |

| O'Connor, Nelly, 524 |

| O'Connor, Wm. Douglas, 9, 48, 74, 128, 130, 282, 337, 349, 351, 504, 521, 563 |

| Otto, W. T., 470, 471 |

| Redpath, James, 460 |

| Rhys, Ernest, 59, 162, 440 |

| Ritter, Fanny Raymond, 483 |

| Roberts, Morley C., 466 |

| Rolleston, T. W., 85, 487 |

| Rossetti, William M., 65, 141, 170, 299, 303, 306, 376 |

| Sanborn, Frank B., 402 |

| Schmidt, Rudolf, 361 |

| Stetson, Carles Walter, 10 |

| Stoddard, Charles Warren, 444 |

| Sullivan, Louis H., 25 |

| Symonds, John Addington, 197 |

| Trowbridge, John T., 506 |

| Van Rensellaer, A., 178 |

| Westness, T. D., 571 |

| Whitman, Walt, 101, 188, 201, 232, 237, 244, 292, 298, 301, 316, 329, 363, 367, 395, 408, 425, 454, 475, 488, 499, 513, 539, 561, 578 |

| Whitman, Sara Helen, 505 |

| Williams, George W., 475, 476 |

| Young, John Russell, 311 |

"I want you to be in possession of data which will equip you after I am gone for making statements, that sort of thing, when necessary. I can't sit down offhand and dictate the story to you, but I can talk with you and give you the documentary evidence here and there, adding a little every day, so as to finally graduate you for the job."

W.W. to H.T., Jan. 9, 1889.

"I don't choose you as a biographer: or anything of that sort—as an authority for this or that: that would n't be an honor, it would only be a burden, to you: no, not that: I only in a sense put certain materials in your hands for you to use at discretion."

W.W. to H.T., Nov. 16, 1888.

"I am disposed to trust myself more and more to your younger body and spirit, knowing, as I do, that you love me, that you will not betray me—more than that (and in a way better than that) that you understand me and can be depended upon to represent me not only vehemently but with authority."

W.W. to H.T., Dec. 10, 1888.

Thursday, November 1, 1888.

7.45 P. M. W. lying on his bed—clothed. Remained recumbent during the time of my stay, except when here and there, in the course of our animated talk, he half rose on his elbow to give some emphasis to a remark. Complained of weariness. I asked him how he had spent the day. "I am not as bad as I might be—not as good as I wish to be." Last night after I left he took a trip down stairs again, alone. "I went silently, so as not to disturb Mary, but I realized my exhaustion." I asked anxiously: "Why do you do that? Why don't you listen to our warnings? Why don't you warn yourself?" He made no kick. I thought he would. He said: "I'll never again attempt to make the trip alone—never: I promise." He said to Mrs. Davis after this experiment: "I see I 'm far gone, Mary: I'll not be with you long, Mary." He has been down on his bed a great part of the day. "I feel weak—exhausted." He speaks less of a rally than he did. "I 'm down a certain distance and there I'll stay till I slip farther down: I 'm not likely to slip up any more." Yet he cheerfully goes his way. He asked me after our hellos were all over: "Did I tell you about yesterday's caller?"—and on my shaking my head: "Well—I intended to: it escaped me." W. went on tersely: " His name was Aldrich"—spelling it carefully: "He is just back from Europe: as I understand it, on his way home: stopped in here: a likely man: we had quite a talk." Then [Begin page 2] he relapsed a minute—all was quiet over on the bed: "He said he dined with Rossetti—William Rossetti—while he was in England." I asked: "Did Rossetti send you any word like Tennyson?" "Ah! no: Rossetti is not effusive: nor is Tennyson for that matter: but Tennyson knew Herbert was coming over—would see me." He added: "But however that be, Rossetti is my friend: he has always borne me in mind—stayed close: he has always done whatever seemed at the moment necessary to demonstrate his loyalty." Aldrich, as W. had said before, had "dined with Rossetti"—"met there once a Frenchman—I think a writer—who said he had seen in one of the great French periodicals some big piece about me—about Leaves of Grass." I asked: "Who was that?—and who wrote the piece?" W. replying: "I don't know either: I do not remember the name of the man Aldrich met: Aldrich did not remember the name of the piece: but I will hear from Aldrich—he said he had memoranda on the subject which he would look up for me." Here he described Aldrich himself. "He is gray, not large, active—a very likeable man—I suppose what they would call in England a tufthunter"—asking me: "You know what a tufthunter is?" and hardly waiting for my nodded assent before going on: "Though that is not peeping out, so far as I could see—not making itself obtrusive." Then he added: "He is from Iowa—has probably make money: is a man of affairs: I noticed that he had a little touch of local pride: he told me of Des Moines—said they have there what he described as the best of the Western capitols—capitol buildings: in one building a suite of rooms dedicated as a public library in which Aldrich himself is a sort of king-pin."

I had met Hunter's daughter this evening on the boat and walked up the street with her, she telling me about her father's sickness (he has been in bed for weeks) and alluding to his later visits to W., which, she said, her father feared had worried W. I said to her: "Walt likes your father—I can assure you likes him to come. There are [Begin page 3] times, of course, when he can see nobody, or, seeing people, can do little talking, but when he is in good condition there are few people he would rather see." W. said very heartily: "I 'm glad you said what you did—mighty glad: glad you said it in that way, as if it came from me." He asked: "So he thought I looked bored? I may have seemed troubled: sometimes that can't be helped: I am not always well—never well in fact: not altogether seeable: but Hunter is always cheery, hearty, interesting: has a story to tell which I want to hear—would not miss—and all that." I read W. Bucke's letter of the thirtieth to me, in which he said on the nurse question: "Still you say nothing definite about Wilkins. Meanwhile W. has written quite a strong letter wanting him sent." W. interrupted me at this point: "Did he say 'strong' letter?"—then: "I don't think that—I don't remember that"—yet confessing that he had written approvingly, much in the temper of his talks on the same subject with me. He no doubt would welcome a change. Yet he does not want to do anything, to say a word, which would seem like wanton criticism of Musgrove. Musgrove is curt, rough, almost surly—creates a bad atmosphere for a sick room. "He has done his best," said W., "but don't quite understand that I 'm a peculiar critter mostly determined to have my own way—not to be unnecessarily interfered with even here, even in my incompetencies." Walt's mild, "I am not disinclined for a change," helps us out of the puzzle. We have not given him any details of the fund which puts the nurse in the house, but he knows of it in general, and in general defers to our notion as to how it should be disposed of.

W. monologued on politics: started off on his own accord and went on for some time about the situation. "I am troubled by the merely mercenary influences that seem to be let loose in current legislation: the hog let loose: the grabber, the stealer, the arrogant honorable so and so: but I still have my faith—in the end my faith prevails. [Begin page 4] It has been my ambition for America that she should permit, excite, high ideals—enlarged views. Take the West case: what a disgrace we made of ourselves out of it! I should have advised, urged, say nothing—don't break the silence by a breath even. Why should n't we allow even to the British minister or any minister or anybody, the largest liberty of opinion and expression?—why not? Why not? Cleveland lost his head—should not have given West his passports. They call it that—"giving him his passports." It was unworthy of Cleveland—unworthy of all of us—was little instead of big: I hate with my whole soul anything that smacks of truckling to our meaner, baser impulses, as this act surely does. I watch the campaign interestedly, but without passion: it has its meanings for me: but it scarcely sinks very deep or goes very high: as I wrote Dr. Bucke the other day, I 'm in no danger of getting worried or excited over it: I feel llike taking the advice of Epictetus to the youth who was bent upon seeing the Roman games—don't get heated, don't fret over results, accept the facts as they appear: wish but this—that the fellow who deserves to win will win: something in that strain." I asked W.: "But suppose neither deserves to win?" He laughed. "There you've got me: abstractly speaking, neither deserves to win: neither Democrats nor Republicans." "But sometimes though neither is good one is not as bad as the other: is that your idea?" "Yes—just that: though I don't get into a boil over it I keep up a devil of a thinking in my corner—my silent thunderings. There are reasons why Cleveland should win—good reasons: then there are reasons the opposite." He shaded his eyes from the light with one hand and lifted himself on his elbow. "Personally I can see no point of view from which it appears desirable to me to elect Harrison. To me the condemnation of Harrison is in his support—in the fact that he is the candidate of all the toploftical conventionalisms of the North—of all that is formal, sectional, schismatic—of all that is commercially iniquitous, [Begin page 5] arrogant, macerating." He said he was anti-Harrison quite apart from his free-trade antagonism. "That would be enough, but there 's vastly more—vastly more: it is a serious consideration to me—the buffet, the slap in the face, which Harrison's election would be to the South: to me it is abhorrent, deplorable, to find all the States of the North on one side, all the States of the South on the other. I know what our people say about that: it 's their fault, our people say: but that don't say it all—not by a long shot. Why is everybody more interested in boundary lines than in unity?—in sects, parties, classes, hates, passions? What a humbug is our so-called civilization if it can't lead us the way out of the jungle! Why North, South—why even America—alone? I know the problem has its difficulties: it must be many years before we heal that old sore." But he had "lived in the South," had "known the meanness of the Southern people" to the full—"known also their strong points." "I can hardly be accused of abasing my high ideals to the Southern contagion: I was anti-slavery, always: the horror of slavery always had a strong hold on me." Yet he "saw other things, too," and refused to "permit one fact to close all other facts out." "I can never forget or deny that the acts of some of the Southern officials, agents who went into rebellion, were as black, perfidious, forbidding, as any known in history: yet these elements of treachery were exceptional: I regard them as exceptional: after all I am an optimist, I suppose: I agree with Dr. Buck that man is better than he was—is constantly growing better still: but there are passions in man to be fought by man to extinction: in our own campaign, here, in America, this year now, there is on one side a spirit of section which must be met and destroyed: I can never condone it. As for free-trade—it is greatly to be desired, not because it is good for America, but because it is good for the world. For Cleveland personally I have no great admiration, though there are some things in him which I like: but the West [Begin page 6] matter, Cleveland's attitude, his official mock heroic indignation, is not creditable to him—rather a blot on his record: a play made to the Paddy O'Reillys and the McMullins."

I said: "Our officialism, most of it, is foreign: it is mainly foreign." W. replied: "So it is: you have touched the nerve: but you have to live in Washington for a time, as I did, to fully comprehend the length to which the tradition is carried: I remember at least one occasion in point during my stay: the question was brought up—the question of officialism, clothes, habit: the question whether a minister should wear a sword, gilt buttons—clothes cut so and so—on demand—to conform with social etiquettical dogmatisms. They all declared to me, in Rome it behooved me to do as the Romans did: to make no demurrer—to take my chances with the rule. I objected—took the ground that men should dress as befitted tastes, habits, necessities, no matter for what the occasion: I did not believe in small clothes, and so forth, and so forth, and so forth. You should have seen the imposing air with which I was sat down on—with which I was assured that if one went to court he should accept the court's dictum." But this was not invariable: "Even officals, usually formal enough, sometimes recognized the tyrrany of the code: we know what happened to Buchanan at the English court. Buchanan (was it from Marcy that he got the appointment under Van Buren?) was a simple, quiet man in his manner: went to a reception—was barred out because he was not formally attired: went home without a murmur. The Queen heard of what had transpired—sent a messenger after Buchanan telling him the Queen would be glad to receive him in any habit he himself elected to adopt: but Buchanan received the messenger slippered in a dressing gown—said he would not go back, and so forth—which seems to me to have been an admirably simple and effective rebuke: it enforces my view—has the American I am in it—or what ought to be the American I am. Sanford, in France, went through the same experience, except [Begin page 7] that he was not barred out: the French court more wisely, less stiffly, construed official right and wrong. But there was Franklin, too: he set the teeth of the French court on edge: his wonderful exceptionalness from the ways of other men—the daring liberties he took—allowed to him probably because of his magnificent personal magnetism,"—"that quality least of all to be defined, yet least to be left out of the qualities of men," as I put it and as he endorsed it with accented warmth—"Amen! Amen! to the end of the chapter!" When he said "good night" to me, I said back: "It sounds so much better to say good night than bad night": to which he replied: "Yes—bad nights don't seem so good as good nights! We 'll only wish bad nights to them who hate!"

Friday, November 2, 1888.

8 P.M. W. reading Pepacton—rather lazily. "I see little in it to hold me: but I had a little notion towards it: I have John humors when I pick up his books and browse with him for a while." Looked pretty well. Yet said in reply to my question: "I can say I am here—little else, nothing else." Sat up near the light: no fire: the evening warmer, as the day had been: the stars out: a touch almost of something that felt like Indian summer. W. particularly interested as always in the state of things outdoors. Questioned me: "Where have you been? What have you been doing?" and so on. Gets great pleasure out of my recital of average experiences—particularly street incidents: likes me to tell him about people I meet—particularly everyday people. "At last and for good I 'm penned up here," said W. He said again: "We hear nothing but politics—cheap politics: cheap and nasty politics: a wearying platitudinous wrangle of politics: with hardly a sincere note anywhere to relieve the tedium of corruption." I showed him The Bulletin of Tuesday containing a review of November Boughs. W. read it while I stood looking [Begin page 8] over his shoulder. "It is kindly," he said—"very kindly: and that is much." Then he added: "Be sure you send the paper to Doctor: he goes wild if he misses a single sliver—he is deadset for curios." Stopping a minute. "The Doctor must have a curious collection: I wonder what it 's all for? I have also sent Doctor a copy of The Transcript in which I found a bit of something which might go into his portfolio." He said again: "That Bulletin fellow does one thing for us—he don't say we are sick. I want the book to be taken on its merits: if it 's a sick book I don't want it excused." "Your being a sick man wouldn't excuse a sick book." "That 's just it: exactly: I want to last whole—don't want to go out piecemeal." I showed W. a letter which I received to-day:

Richfield Springs, N. Y., Oct. 31, 1888.I am illustrating E. C. Stedman's Poets of America, and in it I find mention made of a portrait of Walt Whitman; the one which was in his Leaves of Grass, first edition, and also, I think, in the two volume Centennial edition. I am anxious to get a copy of this portrait, and Mr. Stedman suggests that I may do so through you. Will you kindly inform me whether or no a copy is obtainable, and, if obtainable, the price?

Yours respectfully, William H. Blauvelt.After reading the note W. said: "This means the Linton cut or the steel"—then, as he looked again: "No—it means the steel—it could mean no other: there was no other in that edition"—continuing: "Well—send him the steel. I wonder anyhow why he chose that picture: I wonder: I wonder." He looked at the postmark: "Richfield Springs: ah! I know: the name is familiar: it suggests tone—it is the place for the eight and ten dollars a day fellows: not the ten cents a meal fellows like us: [Begin page 9] no, not us." He asked me about my reading. I mentioned Robert Elsmere and happened to quote the opinion of some one who put Mrs. Ward in the same class as George Eliot. W. exclaimed: "Ah! that 's the woman!—George Eliot! I keep right on reading the book you brought me: I want to read it all: I get more and more interested in her: she was quite the cutest of all women: I have read German Life, Heine, Young—more, too, than them: I can't tell which piece I most like—whether I don't like them all equally well." Then after a pause: "I never supposed George Eliot capable of saying so many good things." I referred to The Impressions of Theophrastus Such. He said: "I think I must have read them—there is an old ring to the name"—then pausing: "Let me see"—putting his finger up against his forehead as if to cudgel his brains—breaking out again finally: "After all, I guess not, Horace: I can hardly have seen the book: I must have taken some one name from another: anyhow, bring the book along: I would like to see it." Talked now and then in a pathetic, hungry way about his friends. "No word from Morse yet: poor Morse! I wonder where he is now? And not a word from John! Oh! I need the fellows—they feed me: lying in here, cribbed here, they are sustenance, life to me. I am sorry for myself when I think how little John writes me nowadays." Then he handed me an O'Connor note with an enclosure. "Look at them," he said: "sit right where you are—read them." I took the letters. Here they are:

Washington, D. C., Nov. 1, 1888. Dear Walt:I was so impressed with the letter Mr. Stetson wrote a year ago about the calendar that I got Grace to send it to me from California, and enclose you a copy, thinking you might like to see it. You can return it sometime, as I have sent back the original. It does not say much, to be sure, and makes me long for such a mind to do the calendar. Don't you think so?

[Begin page 10]The eye is as bad as ever and I see with difficulty. Good bye.

Always faithfully, W. D. O'C. Providence, R. I., 27th July, 1887. Dear Miss Channing:Yours of the 17th came yesterday. I am glad indeed to have such definite information as to what you do not want the calendar to be. I was never so at a loss for an appropriate design, probably because of the greatness of Whitman, of whom I think more highly, and probably more truly, each time I renew my reading.

My idea thus far for a cheap calendar is a nearly square card large enough to hold the three and one-half by four inch days, and a photogravure in some warm tint of the head of the poet, surrounded by a sort of wreath of lilac leaves and pine (with cones and needles of course). I am convinced that pine and lilac are the keynote of the poetry. Then I thought that at the sides I could faintly—I mean delicately—indicate the evolution out of mortality to life that is so strong a feature in many of the poems, by a half-buried inoffensive skull, out of which—or rather the surface of which—merges the "leaves of grass," with their seeds, perhaps. I 'm afraid that will seem to you rather ghastly, but it would not be as I should do it. If there is any one thing that the poems suggest to me, it is the permanent change of all things, but always towards life. Things die constantly, but only to give energy to life by the nourishment of the living. I cannot see any simpler way to express it than by the accepted emblem of death out of which grows grass that so pleases him. I should dearly like to work in something expressive of the enormous sympathy he has with the earth, air, and water, but I confess myself unable to see how to do it in one card with any degree of simplicity and expressiveness.

I had read most of the letter aloud. I stopped at this place. W. said: "Stetson goes on in detail: do you know [Begin page 11] him? He is the painter—the portrait artist: enjoys quite a fame. There 's a line or so at the bottom—farther on: you will like to see it." I looked and repeated this: "I have a horror of the cheap imitation of missal painting that has been in vogue." W. interrupted me: "So have I: I always want the real thing even if it 's real bad." Then he added: "But I am always asking myself about all that calendar business—what's the use? I can't see that it leads to anything worth while: but I 'm not responsible for it: I wash my hands of it." W. also gave me a Bucke letter. He said: "O'Connor writes on the whole as if he was on the mend"—then, after a pause: "I have hoped you would meet him: he has been here several times—yes, I think once when Sidney was here: but I feel dubious: I don't like the look of things: I 'm afraid he 'll never be here again."

I had been to a committee meeting of the Contemporary Club. Gave W. a message from Coates. "Coates is always cheerful, encouraging, gentle. He struck me as that sort of a man: and comfortable, too: perhaps too comfortable—perhaps with a little too big pocket book, God help 'im!" I said to Brinton at the meeting: "Walt has a thorough liking for you." Brinton replied: "I take that as a great honor—a fact to cherish." I quoted this now to W. who said: "Yes, I like him: yet when you tell me of his self congratulation I recall a little story told of Oscar Wilde when he was in this country—in Boston, at some drawing room reception. Wilde said to those there—said it gravely, I think—(at least, I have taken it gravely): 'If I may presume to speak for them—to include myself among them—I should say, it is not your praise, your laudations, that we, the poets, seek, but your comprehension—your recognition of what we stand for and what we effect.'" I drifted into fuller details of my talk with Brinton. "Brinton is simple, candid, forceful, and never flatters: it 's your significance that Brinton first and last of all realizes: he is scientific: he never talks of things he has not examined and never acquiesces in things he does not approve of." W. [Begin page 12] smiled and said: "Amen! Amen! that sounds something like: I see: I see: Brinton is the genuine article—is the typical scientist: in the best of them that spirit is beautiful indeed: the fact, the fact, the divine fact! that 's what they're after."

I read this out of Bucke's letter: "In the afternoon came McKay's November Boughs—for which many thanks. I like it well, and if I had not seen the other should have thought it quite perfect. As it is like YOUR November Boughs with the limp covers the best." But W. shook his head: "But mine was not the best: Maurice likes what I do when I do not like what I do myself." Bucke said this about the change in nurses: "Horace tells me that Musgrove is to leave on Sunday or Monday morning. I have written Ed Wilkins and will have him leave here by 11.40 train Sunday morning. He will reach Philadelphia about 8 A. M. Monday." This seemed to make W. serious. Yet he said: "I guess the shift on the whole will be welcome: no doubt the time has come for it." He put his name on a copy of the title page medallion. "Give it to Acton," he said. Acton is Bilstein's proof-reader. He had expressed himself as "a Whitmanite." W. said: "Give him that: give him that for me. I still find in myself that simple childlike instinct which says, I like you because you like me." And he said further: "I have a great emotional respect for the background people—for the folks who are not generally included—for the absentees, the forgotten: the shy nobodies who in the end are the best of all." A letter was handed him by Mrs. Davis. It had been left by someone at the door. "It is from Hunter: he is better: he says he hopes to get up in person on Sunday to report: he says he has suffered greatly from a boil." W. then added in a laughing way: "It 's always a boil or something: we're all in for it more or less: no one is exempt." W. referred in this way to the two O'Connor letters in Bucke's book: "I think one is as good as the other—they are alike in quality—in power—in immense impetuosity." He asked me as I was leaving: "Well: how do our book affairs get along?" [Begin page 13] He always says our and we. I told him I had taken the original of the title page to Wescott and Thompson to-day for their second trial of an electro.

Saturday, November 3, 1888.

8.15 P. M. W. sitting at the table, his head resting on his hand, his elbow on the arm of the chair. He looked around, hearing me—turned the light up instantly. "Ah!" he exclaimed: "Horace!"—then: "And how are you this day? how goes it with you?" We at once got to talking busily. I stayed a full hour. W. bright, cheery, if not confident, if not vigorous. I handed him a printed copy of the title page. He regarded it with pleased eyes. "I can say it fully meets my expectations: yes, more—that it exceeds the most I could have hoped for." I said: "I like it because there 's no business intimation on it—no publisher's imprint." "Ah!" he said, "you regard that as a sort of esthetic dash?" "Esthetic?" I asked: "what have you to do with estheticism?" He laughed. "Why not? I 'm afraid I would not at all times be out of danger of that—appealing to an art impression, of reaching towards the simply tasteful or beautiful." After a pause: "I of course mean that in the exceptional sense—as an incident, not the main thing."

I described to W. my hunt most of my spare time to-day for the steel plate. I found that Adams had it after all—pushed away somewhere in his shop. W. asked: "What do you suppose Blauvelt intends doing with the steel plate? Is he to illustrate Stedman's book?" I am to inquire and to send the plate on Monday. W. wanted to know what was my "real opinion of the plate," saying then: "William O'Connor fancies it because of its portrayal of the proletarian—the carpenter, builder, mason, mechanic: but I do not share his view: I take real pleasure in it for its execution as a specimen piece of rare engraving: then I like it because it is natural, honest, easy: as spontaneous as you are, as I am, this instant, as we talk together." He gave [Begin page 14] me a copy of the Gutekunst phototype, endorsing it with blue pencil: "Walt Whitman: Nov: 3, 1888." He asked: "Do you think it glum? severe? I have had that suspicion but most people won't hear to it. I called Mary's attention to it once: she is cute, knows me: but she said what you say, that I am wrong: and I hope your view is correct: I don't want to figure anywhere as misanthropic, sour, doubtful: as a discourager—as a putter-out of lights." He referred to Stetson's letter. "It was a noteworthy suggestion—he has the true feel of the genuine painter: I feel its essential verity. I shall send it on to Doctor to remind him that it must go back to William."

W. reached forward to the chair near him and picked off it a copy of The Pall Mall Gazette of the eighteenth of last month. "William Summers has gone home and written a piece. It is good—pretty good: nothing to brag of, but passable. I read it wondering how it came about that I said so much as he quotes. It is not inaccurate: there is a slip now and then: two or three places where I'd like to make changes: but the story at large sticks pretty decently to the facts. You know, I spoke of Summers when he was here—rather favored him. Did I show you Mary Costelloe's letter about him?" "No." "Well, she said he was a man of parts—that he would be a man of far greater prominence if he was not the most inordinately lazy man that ever was born: something like that. Fortunately he 's rich. As for being lazy, I 'm some punkins at that myself, so I guess I readily understand Summers." He pushed the paper into my hand. "I want you to take it along: when you bring it back I'll give it another look and forward it to Bucke." He seemed a bit grave about Wilkins. "He will be here Monday: but will he do? Well—we are to see: if he does as well as Mr. Musgrove I shall be satisfied: if he does better—" Here he broke off.

W. had been turning over old papers to-day: manuscripts and clippings and portraits were wildly strewn across the table and floor. He had asked Mary to bring him up a [Begin page 15] bunch of stuff from down stairs. "I must do something: it 's slow death to sit here with my hands folded: so I am cleaning house, so to speak—looking into old scribbled pieces—throwing a lot of débris away." He got up for something: I walked about with him, he leaning on my shoulder. "The assistance is very welcome, Horace: yet if one allows it, invites it, gives in to it, he comes to need it. I must be on my guard: I must take care not to grow helpless before my time." Warren has been suffering with an abscessed ankle. W. said of it: "He 's knocked up worse than I am now: but then he 's young—he 'll recover: I 'm old—I'll not recover." I met Harrison Morris to-day. He said: "I hope Walt will do me the justice to believe that when I proposed to go over to Camden to see him I had no idea he was so ill." W. now replied: "I do do him that justice: I have never done anything else from the start: tell him that: I am sure I understand: but he knows that I am sick—that conversation wears me out—that I often have to dodge it—that I sit here in a mental physical condition which demands isolation of me. I realize his feeling: tell him so: tell him this."

W. suddenly spoke out briskly as if he had almost forgotten to say something he wanted to speak of. "Now I am in the way of it, Horace, I want to let you know that I took up the Conway book again to-day—sort of fell across it, got interested in it and I read on for fifty pages or more. I mean the Carlyle—Conway's. By the merest accident I struck upon a reference to myself. Conway had had some talk with Carlyle—some talk about democracy: some point arose: he tried to set Carlyle right by quoting me: Carlyle stopping him instantly: 'No—no—don't quote that man! he 's the fellow who thinks he must be a big man because he lives in a big country.'" W. was highly amused. Exploded in quiet chuckles. "It may be I put it a little strong but that 's the gist of it: it consorts mighty well with Carlyle—with the Carlyle we otherwise hear of—his humor, his judgment, as it has been told of so often by so [Begin page 16] many people." He wanted to know this: "Did you ever remark the strong likeness between Goethe and Hicks? Goethe lived in a little slip of a place—a little town interested in small wares—given up to petty, trivial gossipings: yet he glorified himself, glorified the place, by his tremendous vital grasp of eternal principles—by the infinite reach of his faculty—his illimitable intuitions. Goethe would say, Hicks would say: 'It 's not the land a man lives in but the sould he has that makes him big or little, useful or useless.' Oh! there 's a great heap in that: I could not question it: I know it could be argued for, forcibly argued for—perhaps proved: yet I find myself always coming back to my own point of view." "Which is what?" "Oh! have n't I spoken of it often, vehemently enough? of the common man and the common ways? that they too must be included and made much of?" Back then to Conway. "After all," he presently argued: "I was too quick to condemn the Conway books: I pushed them aside the other day just as if they contained no message for me." "I noticed you did: I thought of taking them home again." He placed his hand on mine and looked into my face affectionately. "I noticed that you noticed: but you did n't take them: I am glad now that you did n't. There 's considerably more to the Conway stuff than I supposed: Conway has greatly improved in recent years. Take those last years—the last days—in the Carlyle book: they are better told of there than anywhere else by any other writer. Yet I can't help feeling still a little suspicion of Conway's lack of historic veracity: he romances: he has romanced about me: William says lied: but romanced will do. I don't feel sore or ugly about it: it only makes me watchful. There 's Tom, now: why, he puts Conway way up—in the seventh heaven: they even say he is quite an orator, as maybe he is. He has done too much hack work—that 's the trouble: it damns any man: the fellows allow themselves to need too much money—then they sell out to get it: Conway did more or less: he had the story teller's faculty of [Begin page 17] forcing things. Personally, he has mostly been my friend: and one thing—Conway has always stood for free things—free thought: I can't forget that—don't want to: that atones for much."

Something or other induced me to mention John Boyle O'Reilly. This started W. right off. He is immensely approbrative of O'Reilly always. "Boyle's charm came out of his tremendous fiery personality: he had lived through tremendous experiences which were always appearing somehow reflected in his speech and in his dress and in his attitude of body and mind. I had wonderful talks with him there in Boston when I was doing the Leaves: he came every day. Oh! he is not the typical Irishman: rather, Spanish: poetic, ardent." Then reflectively: "You know his life in outline: he has given me glimpses into it: short, sharp, pathetic look-ins." He stopped a minute. "They were like this: it was in his prison days: the prisoners suffered from bad food or too little food or something: O'Reilly is deputed to present a complaint: he does it: the overseer does not answer—pays no attention whatever: raises his hand, this way"—indicates it—"hits Boyle—slaps him in the mouth—violently—staggers him or knocks him over." Walt had raised his voice. His eyes flashed. "Think of it, Horace!—think of it! what must that have meant to O'Reilly: he was a mere boy, I should say: scarcely twenty or not more: noble, manly, confiding: think of it: try to comprehend it: what it must have aroused and entailed." W. dropped back into his chair: closed his eyes. "It is horrible! horrible!" I did n't intervene. W. after a bit talked on: "O'Reilly has had a memorable life: this is but a sample item: he is full of similar dramatic retrospections: who can fail to be aroused when a man meets you that way stepping right out of a background of vital experience? Here is Kennan, too. I have read him: at first, specifically, deliberately: then with pain: with added grief, more emotion, almost a nightmarish dread: till the horror of it drove me off. I swore I would [Begin page 18] never listen to such stories, read them, again: then something else appears—new material: somebody's confessions—the tales of travellers, investigators: I take it all up once more—can't drop it: the strange, beautiful, haunting emotional appeal dissipating all objections. I swore off Kennan once, twice, many times: now I swear him on again."

We discussed Kennan. I had seen him at the Contemporary meeting. W. asked me many questions re his appearance. "Yes, it must be all there in his face if you can look deep enough: the fierce unforgivable Siberia of his stories." He digressed: "It 's interesting, very—interesting to think of the irrepressible journalist defying danger, penetrating into remote places: coming face to face with alien distant fact: the new fighter on the new plane—the indefatigable gatherer of historic treasure: the surprising paperman: impertinent but pertinent: shameless, often glorious." I said: "Walt, you got the reporter business about right: it 's both divine and devilish: we both know it, don't we?" He seemed to enjoy the idea: "Yes—we 've tasted the fruit of the tree—some of it rotten as hell, some of it sweet as heaven!" Then we got off on another tack. "I was going to say something of things I knew in war time. I have in mind one particular fellow—a North Carolinian—keeper of North Shore light there: a magnificent fellow: not conventionally pretty, but handsome, strong, manly, developed—recognizably so to anyone who knows how the rock, the tree, the stream, has its own beauty. This man had been away to see his wife: was arrested on his return—asked to enter the Southern service. 'How can I? I have given my oath to the Union.' He was impressed, imprisoned—kept so for years—in some hole like Libby or Andersonville. This man in the later years of the War came to Washington: he had been released: came up: I met him: we became friends—saw much of each other: I got to know his whole sad history."

W. recurred to O'Reilly: "Put these things together: [Begin page 19] think of such men: the best sort of men: the plain elect: all their young hopes of life scattered—the blessed joys of camaradarie all crushed out: power, brutality, everywhere to annul, to destroy: everything crushed out of a man but his resentments, the unutterable memories of barbarisms, the heart's uncompromising revolt." W. had this furthur to say about O'Reilly: "His late years have not been as free as the years of his youth—as noble: he is in some respects too much like Cleveland—too much interested in the Irish vote." This political swing led the talk to the campaign. "I don't enthuse: I have my hopes: some, not many—a few (just a few): but after all the fight is between two parties neither one of which has any real faith. I can't help thinking of the Sackville West affair: it disgusts me: I hate anything which looks like a surrender to debased appetites: for instance, now, to-day—the haste of politicians all around to pander to the Irish vote: it is contemptible—all such hypcrisies are contemptible—to the last degree." I repeated to W. what I said to Brinton to-day: "An average Pennsylvanian has no god but the tariff." Brinton had replied: "That is so: yet anybody should see that there is no problem more difficult to decide one way than the tariff." W. said: "The whole tariff business is too damned little to give much time to: it 's only on the surface: the real troubles are profounder: but our time will come: we will keep on with the stir: our time will come: I say to the radicals—the impatient young fellows: wait, don't be in too great a hurry: your day is near: in the meantime hold your own ground—defend what you have already won—look, listen, for the summons: it will come, sure: it can't come too soon." Gave W. a copy of to-day's Star containing some Carlyle matter. "Yes, leave it with me: I 'm sure it 's a thing I should look into: Carlyle is always grist to my mill, no matter what form he comes in or where he comes from." I asked W. if he had any directions to give me about a cover for the book. "Not yet: I must turn the matter [Begin page 20] over: I don't think I want much to do with it. I'll try to get myself so I can tell you what I don't want: then you can proceed on your own account." He picked up the title page and held it in his hand as he said: "John should like this—number two: John Burroughs: it shows the ear: John has very strong notions—physiological, spiritual even—about the importance, the significance, of the ear."

Sunday, November 4, 1888.

7.15 P. M. I found W. writing. "I 'm thinking of a squib for the big book," he said. He thought he would call it "a note in conclusion." Not sure yet, however. His writing pad was on his lap. He had been busy. "I am feeling about a bit to see whether I should or should not write a little prefatory note and perhaps an epilogue—something of the kind. What do you think of the idea? Would it seem superfluous to make the addition?" So far he had been saying: "I guess I'll let the book go as it is: no intermediating words are necessary." Now he says: "If you say yes I'll do yes. What do you say?" I said yes, of course. W. then: "Well—that 's a vote: two for, none against: I'll work on the thing to-morrow—will have the copy for you to-morrow evening. I have spent most of the day arguing it over with myself: I needed you to bring me to a conclusion—to end my vacillation."

W. very cheery. Said he felt "almost flirty" most of the day. "Hunter did not get here: I expected him—wanted him: but Tom came in with Frank and young Mr. Corning. We talked politics: Tom is hot about the election but I don't feel my pulse stirred a bit: even my hopes are only lukewarm: for Cleveland personally, I care nothing: he don't attract me: is rather beefy, elephantine: yet I do care for some of the things he represents. I have no feelings against Harrison as a man: he may be good enough looked at as a hail fellow well met—but so is Dick Turpin: the fact remains that I dread what his election must inevitably [Begin page 21] bring about. No man can look into what we call party politics without seeing what a mockery it all is—how little either Democrats or Republicans know about essential truths." W. said again: "It 's fine to see Tom so hot in the collar but I always wish it was in the interest of something more important: I am always quoting Epictetus myself: he said: 'Don't fret, don't excite yourself: be satisfied: the man who must win will win.': which is an admonition to self-control." He did not like Harrison's attitude towards the South. "I recognize all the flummery of the South—the flummeriness, the tinsel: but I would humor it in that—give it plenty of rope: yes, humor it, as I would a bad boy or a bad horse: humor it, wait, rest my faith in the developmental energies: giving the good a chance to drive out the bad, as it will, is sure to, with time. This may seem like a trifle, but trifles move mountains. I remember a story which Bryant told me. There was a banquet arranged for: the guests came—were gathered about: a waiter brought in a big bowl of soup, placed it on the table: one of the guests took a toothpick, used it and threw it into the soup. That toothpick was a little thing, but it nullified the soup: it was only a detail, a trifle, but it changed the face of that world. This represents the Harrison case to me: Harrison's election could only be that toothpick—and yet! Now," he concluded, "let them all have their useless says: all of them: even The Press man over there in Philadelphia with his damned cartoons, which, if I had a weak stomach, would make me throw up. What do you think of The Press anyway? To me it gets worse and worse: of all the political horrors it is the most horrible horror."

W. passed me back The Star piece about Carlyle: "I read it with considerable interest: it corroborates all that has gone before—is in the usual strain: is genuine: it adds nothing to the Carlyle story but goes over the old ground vividly." He quizzed me. "How does the title page seem to you to-day? Do you think it looks lean? Has it a [Begin page 22] thinnish air? I am more and more interested in the reproduction: Clifford is right—it beats the original: this half-tone gives an effect of richness—in tint, effect, delicacy—that the photo itself does not possess." And he said further: "I am a little suspicious of the picture in one regard: it seems to give me a superior niceness which I have never thought of as an element in my makeup." Referred to "O'Connor's orator nature—his mobile, passionate, high-strung orator nature," and spoke again of William as being "all over eyes to see and ears to hear—his senses are so infinitely comprehensive." Nora Baldwin said to me this afternoon in Germantown: "The carpenter portrait of Walt is prevailingly sad—seems sad first and last—is overpoweringly pathetic to me." W. admitted: "It is open to such a suspicion: it must be touched with what is tragic—the minor key: the idea has been exploited before: even Dr. Bucke has made something of it: but Bucke speaks of it as an elusive, fleeting phase only."

W. picked up The North American Review volume on Lincoln and opened it at his own piece. He pointed to the portrait facing it. "See this: of all the Lincoln pictures this is the best." He looked at it long and earnestly in silence. "I think I must at one time have collected fully fifty pictures of Lincoln: there were lots of them; they were countless: most of them very cheap and hideous—as ugly as the devil. I had a copy of this picture: they wanted it: I sent it for the book. They promised me faithfully they would use it and return it, which they have never done. The figure is better than St. Gaudens'—far better: Lincoln has for the most part been slanderously portrayed. I vividly remember a street view I once had of Lincoln: he was on a balcony speaking to a big crowd—a mixed popular assemblage—a usual American audience—not too still, not too noisy: it affected me powerfully: Lincoln stood just as we see him here—he had one hand behind him, he was in spite of his speechifying calm and in a way reposed: his face—its fine rugged lines—was [Begin page 23] lighted up: it seemed removed, beyond, disembodied: I see it all over again now: this picture is like enough to have been seized out of that scene." Then he spoke of photography itself. "The art is growing with strides and leaps: God knows what it will come to: some of the smart wide awake fellows even back in that Lincoln time had a knack of catching life on the run, in a flash, as it shifted, moved, evolved." Don Piatt's name was there before us in the Lincoln book. W. remarked: "He makes me think of a sloop, a yacht, without an anchor, that would forever keep on going like hell." He spoke of Piatt's "fermentative lightness." "The only thing in Piatt that interests me is his free-tradeism: the free-trade principle is like the sun—it shines upon the good and the bad alike: Piatt has a right to his evil and his free-trade, both: he is a fiery cuss who burns but does not shine."

W. asked me further about the Germantown party at Clifford's. Some one there had asked about W.'s weight at the the time the steel was made. W. said: "I should say about forty pounds less than for the last twenty years—about a hundred and sixty-five or thereabouts: I formerly lacked in flesh, though I was not thin: I was less fleshy than in after years—had less belly—though I never had belly in excess—was never at all portly: I had a good liberal frame—was all right that way: I owed a lot to my mothers and fathers." Another question came up. Had Sam Longfellow been over during his occupancy of the Germantown Unitarian pulpit which Clifford now has charge of? Clifford said: "He must have been here at the time of the Boston affair: if so, if he was Walt's friend, it was his place to call—to put himself on record by Walt's side." W. said to that: "I should never have thought of that myself but now that Clifford says it I can see very well why it should have been said. I don't think Sam was ever here: I may have met him over there in the city—in Germantown—though even that seems doubtful. Sam is a fellow who would not do anything to [Begin page 24] endanger his share of a good dinner—of one or two thousand a year. I know very well that this is not so of Clifford: it would not be like him: being brave, on the right side, uncompromising, goes of course with such a man."

Clifford had said to me: "Sam Longfellow is in some ways at least a more powerful figure than Henry." W. took that up when I repeated it. "I have said that to myself more than a few times: but then I am not sure enough of my ground to dogmatize about it. Perhaps Sam is like our man there in The Pall Mall Gazette as Mary Costelloe describes him—inordinately lazy. Henry's face does not suggest strength: no—not at all: it suggests grace, finish, affability, sweetness, suavity." I alluded to the Longfellow diary notes in Sam's Life of Henry as "almost insipid." W. took me up. "Regarding them critically that probably might be said—but you must not regard them critically. Take Longfellow for what he was: a man of a certain sort, of his own sort (more or less traditional, according to rule)—as necessary as men to whom we would attribute an ampler genius, larger purposes. Longfellow was no revolutionaire: never travelled new paths: of course never broke new paths: in fact was a man who shrank from unusual things—from what was highly colored, dynamic, drastic. Longfellow was the expresser of the common themes—of the little songs of the masses—perhaps will always have some vogue among average readers of English. Such a man is always in order—could not be dispensed with—maintains a popular conventional pertinency."

I said: "Clifford spoke of O'Connor's two letters as unmatched in English literature." W. at once assented: "There is nothing in their line anywhere near equal to them: William was vehement: he was boundless in his forthreach: he went into the anti-slavery fight hot, ripe, for all encounters: transcendentally powerful: enjoyed the smoke of battle: had not fire in his eye (his eye was gentle) [Begin page 25] but certainly was a burning bush of justice. I was always anti-slavery myself but never was able wholly to sympathize with O'Connor's fervid dead-earnestness." I cited Emerson's "what right have you to your one virtue?" But Walt dissented: "I don't know that it was for Emerson's reason or for any conscious reason: I felt, I feel, that the cosmos includes Emperors as well as Presidents, good as well as bad. Why should n't I?" W. stuck his fingers under some papers on the table and pulled out a letter which he handed me. "Read that," he said: "it 's not new according to the calendar but it 's brand new according to its goodwill. Read it aloud: I 've read it often but I'd like to hear it again." So I read.

Chicago, Feb. 3rd, 1887. My dear and honored Walt Whitman:It is less than a year ago that I made your acquaintance so to speak, quite by accident, searching among the shelves of a book store. I was attracted by the curious title: Leaves of Grass, opened the book at random, and my eyes met the lines of Elemental Drifts. You then and there entered my soul, have not departed, and never will depart.

Be assured that there is as least one (and I hope there are many others) who understands you as you wish to be understood; one, moreover, who has weighed you in the balance of his intuition and finds you the greatest of poets.

To a man who can resolve himself into subtle unison with Nature and Humanity as you have done, who can blend the soul harmoniously with materials, who sees good in all and overflows in sympathy toward all things, enfolding them with his spirit: to such a man I joyfully give the name of Poet—the most precious of all names.

At the time I first met your work, I was engaged upon the essay which I herewith send you. I had just finished Decadence. In the Spring Song and the Song of the Depths my orbit responded to the new attracting sun. I send you this essay because it is your opinion above all [Begin page 26] other opinions that I should most highly value. What you may say in praise or encouragement will please me, but sympathetic surgery will better please. I know that I am not presuming, for have you not said: "I concentrate toward them that are nigh"—"will you speak before I am gone? Will you prove already too late?"

After all, words fail me in writing to you. Imagine that I have expressed to you my sincere conviction of what I owe to you.

The essay is my first effort at the age of thirty. I, too, "have sweated through fog with linguists and contenders." I, too, "have pried through the strata, analyzed to a hair," reaching for the basis of a virile and indigenous art. Holding on in silence to this day, for fear of foolish utterances, I hope at least that my words may carry the weight of conviction.

Trusting that it may not be in vain that I hope to hear from you, believe me, noble man, affectionately your distant friend,

Louis H. Sullivan.When I was through W. asked: "Ain't that catchin'? It sounds like something good that comes along on the wind for them as know enough to suck in. I'd say that feller's some shucks himself: whatever he does I'll bet he does big: he writes as if he reached way round things and encircled them. He 's an architect or something: and he 's a man for sure. Take the letter along, Horace: keep it near you: use it now and then when it comes in just right."

I had casually mentioned Harrison Morris: W. thereupon suddenly starting to hunt something up among his papers—finally pulling out a copy of The Poetry of the Future—a pamphlet such as he had sent to Jerome Buck. W. said then to me: "Show this to Morris sometime: There 's a passage along here which exactly meets his case." Turning to page 202, he marked the following with his [Begin page 27] blue pencil, saying at the same time: "They sent me several of these pamphlets from New York there: I think Bromley had a hand in it: you know it is Bromley who sent me this book"—holding up the Lincoln volume: "He is a Friend."

"Is there not even now, indeed, an evolution—a departure from the masters? Venerable and unsurpassable after their kind as are the old works, and always unspeakably precious as studies (for Americans more than any other people), is it too much to say that by the shifted combinations of the modern mind the whole underlying theory of first-class verse has changed? 'Formerly, during the period termed classic,' says Sainte-Beuve, 'when literature was governed by recognized rules, he was considered the best poet who had composed the most perfect work, the most beautiful poem, the most intelligible, the most agreeable to read, the most complete in every respect—the Æneid, the Gerusalemme, a fine tragedy. To-day, something else is wanted. For us the greatest poet is he who in his best works most stimulates the reader's imagination and reflection, who excites him the most himself to poetize. The greatest poet is not he who has done the best; it is he who suggests the most; he, not all of whose meaning is at first obvious, and who leaves you much to desire, to explain, to study, much to complete in your turn.'"

Monday, November 5, 1888.

7.50 P. M. W. reading George Eliot. Very cheerful though speaking of an only "tolerable day." I asked him at once: "Did you get the manuscript completed to-day?" He answered: "No, I could not make it fit: it would not come out as I wished it." He had attempted it. "The prefatory note is satisfactory—all done: the other is helter-skelter." He would stick to it. "If I can't manage it in a day or two I must let it all go." I protested: "But you will manage: if you have anything to say you must [Begin page 28] find a way to say it: if you have nothing to say why write at all?" He seemed to spur up. "That is wholly true: you give me my resolution back: I have something I want to say: I still expect to find a way to get it said: I feel that it will come if I but wait." I had sent the picture to Blauvelt and asked him what he intended to use it for. W. assented. I read W. a postcard received from Burroughs to-day:

West Park, N. Y., Nov. 2, '88. Dear Horace:I rec'd the book all right and wrote so to W. W. in a few days. Many many thanks. I shall find time to read it by and by. I see there are new things in it. I am busy with the farm these fine days and pretty well. I hardly need to tell you how much joy your letters have of late given me. With love to W. W. and yourself.

J. B.W. said: "I guess John wrote if he says so, but the letter never reached me. If you write tell him this. Make it plain to him always that he is eminently present to me always here: no matter what happens, remains vitally with me, sharing my life." He reached towards the table. "I have had a letter to show you: it came to-day: from Sidney—Sidney Morse: I laid it out somewhere for you." He struck upon it after considerable difficulty. "It is in his worst hand." I was looking it over. "But in his best heart," I said. He said: "Yes, that: Sidney is notable for fellowship: radiates, illumines: is the whole, not the piece, of a man." Brinton informs me that Ingersoll's name is taboo in The Ledger office—is prohibited by a standing order. I said to W.: "To judge by the rare appearance of your name there you must be under a similar ban." W. rejected this idea: "Hardly—hardly me: McKean would not go to that extreme: indeed, I am occasionally referred to, and kindly, though without enthusiasm."

I reported to W. that Acton was proud to have the portrait. W. was happy over it: "It 's fine to be able to do [Begin page 29] things to make people happy: I like to confer unsolicited benefits—to give people what they don't ask for: I dread the spoils hunters, especially the autographists: but I am willing to please the rest of folks all I can." Had the new nurse turned up yet? W. laughed. "Now—that 's funny: why did n't we speak of that before? Ed? Yes: I think he 's in the next room this minute"—calling out: "Ed! Ed!"—and when Ed seemed not to hear: "Open the door, Horace"—I doing it and W. calling again: "Ed! Ed!"—Wilkins coming in at that and towards me. W. introduced us. "Ed, this is one of my friends—this is Horace Traubel." Ed scanned me. He was tall, young, ruddy, dynamic. W. regarded him approvingly. Ed had been writing. He stood, his arms folded up, against the foot of the bed. He was in his shirt sleeves. There was a half smile on his face. I moved about, sitting, standing, in different places.

W. talked freely of various things, Ed remaining. W. addressed himself to Ed: "Do you know that you have plunged into the very heart of protectionism? that the merest breath against the tariff is blasphemy here? stirs the whole community against you? Some one says, if you have an odious law, enforce it—let it be seen for what it is: maybe: Grant said something of the same import: there may be good sense, philosophy, in the idea: but the question is, can you enforce it? If most people or a tremendous mass of the people (a large minority) is against it, can it be enforced?" Then he inquired playfully of Ed: "But There 's nothing to keep Canadians out, is there? If a Canadian chooses to come over what shall we do with him? That raises a point which if settled humanly right impeaches the whole system." I asked if Bucke was an out and out free-trader. W. seemed uncertain: "I don't know: don't remember that we ever talked of it: but he should be—it would seem logical for him to be: by his antecedents, tastes, training in science: what else could he be? It would seem like gross self-contradiction for Maurice [Begin page 30] to have any tariff notions whatsoever." W. said again: "The tariff business is all flub-dub anyway."

W. asked me some questions having to do with to-morrow's election. "I'd like to smash out two damnable idols—the tariff and the bloody shirt. I don't want to see Harrison elected: yet I don't anticipate anything special from the election of Cleveland—in fact, from any President as Presidents go, with party policies as they are these days. We have in a sense been fortunate in our Presidents: no matter what their backgrounds may have been the Presidents after they become Presidents have borne themselves well—the whole line of them: carried themselves according to their lights"—"Yes, dim as some of their lights have been," I interrupted—he was laughing: "Yes, dim as some of them undoubtedly were. But if they had all of them except Lincoln been inadequate, impossible, he would have redeemed, justified, the tribe." Then after a pause: "But there have been other forcible goodsized men: there was Jackson: he was a great character: true gold: not a line false or for effect—unmined, unforged, unanything, in fact—anything wholly done, completed—just the genuine ore in the rough. Jackson had something of Carlyle in him: a touch of irascibility: quarrelsome, testy, threatening humors: still was always finally honest, like Carlyle: Jackson was virile and instant. Look at some of the other Presidents: take Andy Johnson and Frank Pierce, who were the worst of the lot: they tried every way they know how to steady up—to redeem themselves from their weaknesses. Take Buchanan: he was perhaps the weakest of the President tribe—the very unablest: he was a gentleman—meant to do well—was almost basely inert in the one crisis of his career: though at the last, in the two or three weeks before his retirement, he came to himself, stood straight again, saved his soul. It goes much so all the way on. Start with Washington: come down to our own day—to Cleveland: the selection of men from the first to last registered a certain average of success. We are too apt to pause with [Begin page 31] particulars: the Presidency has a significance, a meaning, broader, higher, than could be imparted to it by any individual however spacious, satisfying. There is no great importance attaching to Presidents regarding them simply as individuals put into the chair after a partisan fight: the Presidency stands for a profounder fact: consider that: detached from that it is an incumbrance indeed, not a lift, to the spirit. We need to enclose the principle of the Presidency in this conception: here is the summing up, the essence, the eventuation, of the will of sixty millions of people of all races, colors, origins, inextricably intermixed: for true or false the sovereign statement of the popular hope."

W. dropped the political talk here. He produced from under some other papers what proved to be an "undecipherable" letter. "Here is a specimen note from one of the illegibles," he said. I turned it over. "Read it if you can," he said. I asked: "Can't you read it?" He answered: "It has never been read so far as I know: I never have read it: I read enough of it to get its purport: I managed to read the postcript, which was meant for me." I commenced to puzzle over it. W. demurred: "I wouldn't bother with it now: take it with you: devote yourself to it some day when the time hangs heavy on your hands." "You call Houghton one of the illegibles?" "Yes: there are two illegibles: Miller is one, Houghton is the other: curiously enough this letter is from one to the other." "I wonder how they like taking each other's medicine?" W. broke into a hearty laugh. "I wonder?"

Chicago, Sept. 4. My dear Miller:Here I am in the heart of the old country and directly on the borders of the new. We (I and my son) have had three pleasant weeks in Canada—a Dominion not to be snubbed as you Americans are in the habit of doing.

I don't know how you have found your way to that "inferior [Begin page 32] Europe," as you call the Northern cities. I told everybody you were going to Japan and India—but this was on your own authority—which of course I ought n't to have cared for.

I myself expect to be there about the 29th and shall stay in the neighborhood of New York and Boston through October. My son returns on the 29th to England, to the University of Cambridge.

I have been intending to write every day to Mr. B—— in answer to his cordial letter but did not like to do so till my plans were a little clearer. I shall do so as soon as I have quite made them out.

I have to thank you for verse and prose. I did not care for the subject of your Poem as much as for that of your others but the treatment and diction are very powerful. The story of the Sierras has the difficulty of following Bret Harte. I wish you had been the first in that field. You would have done it as well and won both fame and gold. The publishers said your Italian novel would be out soon. I await it with interest.

Please give my best regard to Mr. Whitman.

I am yours very truly Houghton.W. said: "Miller sent me that letter on account of the postcript, but it is, all of it, a valuable example of touch and go from a traveller. I have talked with you before about Miller and Houghton: Miller, rugged, careless, happy-go-lucky, earthy: Houghton, titled, refined, cultivated, in a certain sense an elect: they were both my friends: I feel warm towards them—towards their work. Miller's work? Oh! Miller has broken loose some—been more or less free in technique: Houghton wrote in the old ways, hugging the traditions."

John Forney is often spoken of in Philadelphia as Buchanan's son. W. said: "I never heard of that. I do not believe it. Yet I have been aware of Buchanan's signal [Begin page 33] interest in Forney. Forney I knew well: liked him, honored him: he was warm—a man of passion: a strong anti-slavery man—stronger than I ever was: I always was anti-slavery, but I never looked at slavery as the beginning and end of crimes. His presence was fine in the extreme—was noble, fascinating." I described a speech I had heard from Forney on election night 1876 to a crowd of bitter disappointed Republicans. He spoke from his bay window on Seventh Street. It looked as though Hayes was defeated. I stood in the torchlit crowd. W. said: "Oh! that is graphic to me: I can see it all: Forney was just the right man to figure in such an episode."

Clifford said yesterday: "If Doctor Bucke is to come on and comes out here why should n't he speak some Sunday from my pulpit?" I repeated this to Bucke in writing to-day. W. said: "What you tell me is surprising: Clifford must have a phenomenal church: he is himself phenomenal. Did I say what you tell me is surprising? Well—I hardly meant that: it would be surprising emanating from any other man: coming from Clifford it seem natural enough." I asked: "Suppose Bucke should give them a Leaves of Grass sermon?" W. answered: "Suppose? I can hardly conceive of it: they have never made much of us in pulpits: I know of no case: there have been allusions—some of them strong (some kindly enough): but for the most part we have been ignored or damned." He said Conway when in Cincinnati had treated him liberally. "But then Conway is not the man we find Clifford to be—not as true, not of nearly equal weight and measure, however brillant." He advised: "Don't take Bucke's simple no as sufficient: insist upon the speech: let him come down: tell him of a Saturday evening without ceremony, $lsquo;Your sermon comes on to-morrow morning$rsquo;: he will go, find his message, speak. Maurice has his head full of things which people over there might like to hear."

Harned came in. He sat on the edge of the sofa. W. asked: "Tom, who's going to be elected?" Tom did n't [Begin page 34] answer direct. He made some general remarks. W. said: "Of course you will vote for Harrison"—adding: "You 're chained—you have to." Tom looked annoyed—seemed about to put in his dissent. W. stopped him: "I don't mean that invidiously: I mean it fairly: chained as I am often conscious I am chained: old habits, associations, speculations, hopes, reasserting themselves." W. said: "Tom—here is Ed Wilkins: Ed, this is my friend Tom Harned." Then he said, with Ed still present: "If Ed suits as well as Baker and Musgrove I'll be satisfied: he has got to prove himself." Musgrove is greatly disturbed. When he settled with Harned he was completely out of humor. W. said: "I saw that, too: he is put out—indeed I may say, mad." W. is glad of the change. That is easily seen. But he is unwilling to have Musgrove imagine that he rejoices in his retirement. W. said as I left: "You are getting to be more important to me than my right arm: I suppose I might get along somehow without you, but I don't like to think I could: somehow, needing you, and having you respond to my need, seems entirely right for us both. That 's how it looks to me: and you?—how does it look to you?"

Tuesday, November 6, 1888.

7.15 P. M. W. lying on the bed when I came, but at once got up and with my assistance crossed the room to his chair. Seemed extra heavy and weak on his pins. Very bright. Talked of many things. I had brought him The Impressions of Theophrastus Such. He took it, repeated its title line, went over the subheads. "No doubt," he said, "the matter is better than the manner"—putting his forefinger down on the list of themes: "The old essayists, the Addison fellows, would say, On Power, On Love—all that: it was their custom, tradition: on this, on the other." I said: "Emerson used the simplified caption—Power, Love, and so on." "Yes," W. nodded: "it was justified in him: I only hope my own titles will be justified in me." "George [Begin page 35] Eliot hasn't your gift for headlining." "I don't know about myself: she seems to have no great trick in that direction: yet I would be happy if I felt that I could do as well." He asked: "Have you ever seen a portrait of George Eliot that impressed you as being adequate? I never have. I have seen portraits, but they don't look probable: they are heavy, torpid, inert. George Sand's face was alluring: it was aged in the portraits I saw, but still cheerful, bright: it was poetic, expressed power, saw up and around." He brushed his hand across the hair on the top of his head. "She wore her hair so." "Do you rather prefer Sand?" "I can hardly say that: both women were formidable: they had, each one had, their own perfections: I am not inclined to decide between them: I consider them essentially akin in their exceptional eminent exalted genius. Yet my heart turns to Sand: I regard her as the brightest woman ever born." Better than Hugo as a novel writer? "Oh! greatly! Why, read Consuelo: see if you don't think so yourself: it will open your eyes: it displays the most marvellous verity and temperance: no false color—not a bit: no superfluous flesh—not an ounce: suggests an athlete, a soldier, stripped of all ornament, prepared for the fight—absolutely no flummery about her. She was Dantesque in her rigid fidelity to nature—her imagery: she led a peculiar life—obeyed the law of her personal temperament: she redeems woman." "Do you think woman needs redeeming?" "No indeed: no, no, no: I do not use the word in that sense: I had in mind the question, what is woman's place, function, in the complexity of our social life? Can women create, as man creates, in the arts? rank with the master craftsmen? I mean it in that way. It has been a historic question. Well—George Eliot, George Sand, have answered it: have contradicted the denial with a supreme affirmation."

Reference having been made to Shakespeare, W. said: "Shakespeare shows undoubted defects: he often uses a hundred words where a dozen would do: it is true that there [Begin page 36] are many pithy terse sentences everywhere: but there are countless prolixities: though as for the overabundances of words more might be said: as, for instance, that he was not ignorantly prolific: that he was like nature itself: nature, with her trees, the oceans: nature, saying 'there 's lots of this, infinitudes of it—therefore, why spare it? If you ask for ten I give you a hundred, for a hundred I give you a thousand, for a thousand I give you ten thousand.' It may be that we should look at it in that way: not complain of it: rather understand its amazing intimations."

W. had read the George Eliot letters "after a fashion," as he described it: "Looked over them: but I want to particularize: I want to go carefully through the whole series." W. gave me Bucke's letter of the 4th. "Read the first sentence or two," he said: "it 's rich." I opened the letter and did so. Bucke wrote: "Gave the first lecture of the course yesterday morning—a demonstration of the brain—cerebral statics—the next will deal with cerebral dynamics (what grand names we give to our various ignorances!)." W. laughed. "Our various ignorances! how immense that is! it specifies, contains, the whole of a great truth: exhibits the whole weakness of professionalism in three words: 'what grand names we give our various ignorances': how perfect that is—how it says all, leaves nothing to be added: our various ignorances: scientific, priestly, literary: our various ignorances: oh! Maurice, you are none too vehement: 'our various ignorances': Amen! Amen!" I said: "Bucke is impatient for the big book." He said: "Tell Maurice to give the big book time: you can't shift the tide ahead of its own pleasure: it comes in, it goes out, according to its own leisurely law." Read Donaldson's piece in to-day's Press on Phil Sheridan: called it "wonderfully interesting"—adding: "Sheridan is always a fierce flaming fiery figure." I laughed: "What are you laughing about?" he asked. "Your alliteration: it sounds like Swinburne." He was unconscious of what he had done. I repeated the phrase back to him. "Sure enough—that [Begin page 37] has a Swinburnesque fling: we must n't flirt our phrases so much." He said: "A letter came along to-day from Tom: quite a fat one: and then something more: wine, California wine—some he said he had had eighteen years: champagne: and back here," he added, pointing behind the chair, "some fruit—the best: I shall surely make a raid on it pretty soon." "What about that wine? Bucke puts a ban upon it." "The way I have felt the last two or three days I owe myself a glass now and then: Maurice is all right: the wine is all right, too: sometimes even Maurice must be adjourned!"

Had he done any work on the Note to-day? "No: I did not touch it: it does not come to me: something holds me back: if a day or two more passes without an inspiration I'll let the thing drop." "But they won't," I put in: "the inspiration always comes in the end." "Yes: that has been so far true." "If you could lay it aside, take a walk out, ride across the river, loaf a bit in the streets, the secret would come back to you at once!" "Ah!" he said: "that would be the solution of it all: that was my old way: a walk to the river, a look up at the stars, a trip to Timber Creek: oh! those days at Timber Creek! If anything went wrong I would get my stick and hobble down to the water." Then he paused, closed his eyes. "Those old days! those old days! they are past—gone forever!" I said to him: "After awhile I 'm going over to the city to mix in the crowd and see the election returns." He was immediately interested. "If I had leges for it I'd go with you: in the old days I never missed it: until very lately, never missed it: as long as I could keep on my pins: now that I cannot go you must be my scout: you must go around, peering into everything, reporting by and by at headquarters!" He asked: "Did you hear anything on your way home to-night? It 's just as well not to get into a stew over it. I think of Emerson's 'why so hot, my little man?' That seems to me to apply—I adopt it. Have you noticed how these tides—these [Begin page 38] noisy currents—rush past, and the people hardly give them a thought? There may be a quarter of a million people out on the streets of Philadelphia to-night: yet the vast majority of people stay at home, pay little attention to the splutter, attend to their own personal affairs—go their own individual ways: and the great world goes on and goes on whatever for God knows: on and on unhurried, undeterred."