Monday, January 21, 1889

Monday, January 21, 1889

8.15 P.M. Harned stopped in to see me at home, so when I got in at W.'s it was a little late. W. sitting in chair—light turned down, evidently dozing. I stirred him up when I entered. He exclaimed heartily: "Ah Horace! I had almost given you up!" at the same time extending his hand. Spoke of his health at once, I having asked how he was. "Another day of the late usual kind but no grip: no pain, either—no prospect of getting off this low plane!" Very often refers to his "low plane" of present living—to the "weight that bears" him "down." And though not discouraged—as he never will be to the last—he is disposed to acknowledge that he "can never be better than" he is "today." Visitors are few. The few who come see him but for a minute. "I seem to need yet cannot receive visitors." He said tonight, "I'm crazy for that which I have no right to." And he added: "See how isolated I am, shut off irrevocably as I am from freedom—from the world." He picked up my hand and pressed it. "You are my one vital means of connection with the world—the one live wire left. I sit here some days and wonder what would become of me if you were removed—if something happened to you or if you got disgusted with me." I said: "You know, of course, that something might happen to me, but you should also know that nothing could disgust me." He asked: "Why not disgust you? Couldn't I do something that would disgust you?" I shook my head. "No?" "No. Can't you believe that a man's love when it's whole gets beyond being either pleased or disgusted." He was quiet for a few seconds. He looked towards the window. Then he looked down at his hands, feeling one [Begin page 2] hand with the other. Then he looked me in the face and smiled. "Yes: I see what you mean: you are right: you make me feel secure." I laughed and said: "Why, Walt, even if you told me the great secret it'd make no difference to me!" He grew serious at once. "Oh yes: the great secret: it might test you: but I believe what you say." But he added nothing. Did not seem disposed to talk more on that line. I was hoping he'd talk out at last on that long postponed mystery.

W. picked up a newspaper piece on November Boughs. "Some one sent this to me: it has the usual echoey character." Then he added: "These newspaper things while not weighty still say as much as could be expected from such casual sources. The newspaper is so fleeting: is so like a thing gone as quick as come: has no life, so to speak: its birth and death are almost coterminous." He thought "on the whole" he was being "far more generously treated as a penman by newspapers and magazines than formerly." "Why," he added: "if it keeps on like this, some day they may even forgive me for having written Leaves of Grass." He went on: "The gentle Emerson said to me in Boston that time when we had the long walk together: 'We must always remember, Mr. Whitman, that the world will make amends for all this some day.' I asked him: 'For all what?' He looked at me placidly and said: 'I know why you ask, For all what? and I will answer by saying: For everything.' "

Morse had sent me a copy of the Chicago Mail containing a full text of the decision in the Anarchist case. W. looked it over. "Sidney felt that I didn't quite realize the exceptionalness of that incident. Maybe he was right. I seem to be weak on the protagonist side." And he added: "Leave the paper: it may be more important to me than to you: it may remove my prejudices." I asked: "What prejudices have you?" "Prejudices against bombs, for one thing." "It seems to me you have some prejudices against courts and jails and policemen and soldiers too." He took this up sharply: "So I have: prejudices: not against persons: no: against the institutions that require them—that are built on, are perpetuated by, are shamed by, them."

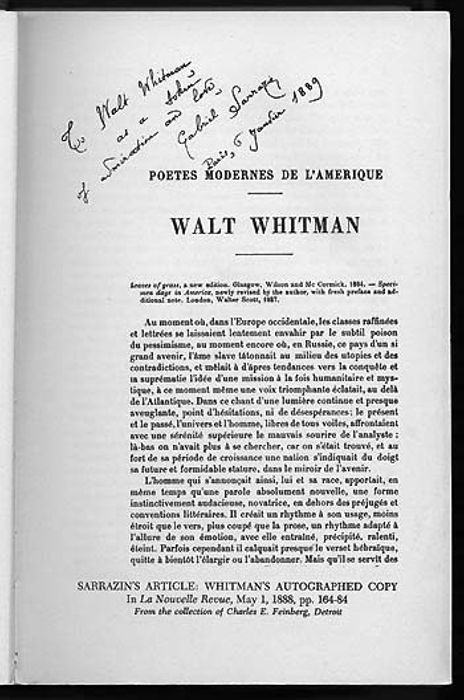

W. called my attention to a copy of a French review containing a Whitman essay by Gabriel Sarrazin. "I suppose it will eventually go to Bucke: I thought I might send it to him by way of Kennedy: perhaps I shall: they can tell me what it comes to. I can't read a word of it. I see Dr. Bucke and John Burroughs referred to but just how,

[Begin page figure-001]

[Begin page 3] God knows: French or Greek, they are one to me. If I only had my old French friend here—if he was living now—the job could easily be done: he would sit down right here, casually—give it to us viva voce." I said: "Perhaps my father can do it: I'll ask him."

"Evidently it went through without being proof-read by Sarrazin," W. remarked quietly: "it is full of emendations—changes: besides, he says in his letter—did I tell you he sent a letter along with it?—that this is not the whole matter—that he will use it in full in some volume he is to bring out." W. handed me the letter. It was written in English. S. speaks of former W.W. translations into the French: alludes to Griffin's work. W. said: "I have seen Laforgue's work: I am told it is brilliant—sparkles. These odds and ends of attention so to speak all get to me sometime or other from somebody: some of them, most of them, are about the house somewhere—or should be: it's my intention to turn them over to you when they show up." Sarrazin has addressed the letter to "Middle" Street. W. enjoyed this. "I suppose he had never been told where he was taught that 'many a mickle makes a muckle' as we were: so he would never have guessed either a mickle or a muckle street. But letters come to me all ways: even the letters addressed by some people more daring than others to 'Walt Whitman, America.' " I put in: "Some day they'll know where to find you if a letter is just addressed to 'Walt Whitman, World'!" He didn't take this up but pointed towards my coat. "What's that you've got in your pocket? Something to show me?" It was a copy of the Bazar. I handed it to him. "Yes! something for you to see: look at this picture: it's by Julien Dupré: it's your sort of a picture: what you call a Leaves of Grass picture." He put on his glasses and held the paper away from him as he looked. The picture was called The Haymaker. "You are sure I'll like it? I do like it: more and more: the more I see of it: Oh! it sinks into me deep. It is Millet: he has studied Millet: subject, treatment, atmosphere: but Millet would not have done that"—pointing to the face—"he would not have made her beautiful, a Maud Muller: no: he would rather have made her heavy, commonplace, almost sullen." But this was "only a minor drawback."

"The picture as a whole is certainly vital—stirring, generic." He reached forward picking up the French review again. "See this"—opening it after some search at a sketch of a man at a table eating: "Don't you think it's superb?—quick, natural, good,

[Begin page 4] conclusive?" Then he got back to the Dupré. "But this is more spacious—is rather more amply conceived." And he added: "I care nothing at all for some of the brazen art: the mere exhibitions of skilful painting: they rather horrify than attract me—are something like treason. I think of art as something to serve the people—the mass: when it fails to do that it's false to its promises: just as if a man would issue a note which from the first he has no intention of paying."

[Begin page 3] God knows: French or Greek, they are one to me. If I only had my old French friend here—if he was living now—the job could easily be done: he would sit down right here, casually—give it to us viva voce." I said: "Perhaps my father can do it: I'll ask him."

"Evidently it went through without being proof-read by Sarrazin," W. remarked quietly: "it is full of emendations—changes: besides, he says in his letter—did I tell you he sent a letter along with it?—that this is not the whole matter—that he will use it in full in some volume he is to bring out." W. handed me the letter. It was written in English. S. speaks of former W.W. translations into the French: alludes to Griffin's work. W. said: "I have seen Laforgue's work: I am told it is brilliant—sparkles. These odds and ends of attention so to speak all get to me sometime or other from somebody: some of them, most of them, are about the house somewhere—or should be: it's my intention to turn them over to you when they show up." Sarrazin has addressed the letter to "Middle" Street. W. enjoyed this. "I suppose he had never been told where he was taught that 'many a mickle makes a muckle' as we were: so he would never have guessed either a mickle or a muckle street. But letters come to me all ways: even the letters addressed by some people more daring than others to 'Walt Whitman, America.' " I put in: "Some day they'll know where to find you if a letter is just addressed to 'Walt Whitman, World'!" He didn't take this up but pointed towards my coat. "What's that you've got in your pocket? Something to show me?" It was a copy of the Bazar. I handed it to him. "Yes! something for you to see: look at this picture: it's by Julien Dupré: it's your sort of a picture: what you call a Leaves of Grass picture." He put on his glasses and held the paper away from him as he looked. The picture was called The Haymaker. "You are sure I'll like it? I do like it: more and more: the more I see of it: Oh! it sinks into me deep. It is Millet: he has studied Millet: subject, treatment, atmosphere: but Millet would not have done that"—pointing to the face—"he would not have made her beautiful, a Maud Muller: no: he would rather have made her heavy, commonplace, almost sullen." But this was "only a minor drawback."

"The picture as a whole is certainly vital—stirring, generic." He reached forward picking up the French review again. "See this"—opening it after some search at a sketch of a man at a table eating: "Don't you think it's superb?—quick, natural, good,

[Begin page 4] conclusive?" Then he got back to the Dupré. "But this is more spacious—is rather more amply conceived." And he added: "I care nothing at all for some of the brazen art: the mere exhibitions of skilful painting: they rather horrify than attract me—are something like treason. I think of art as something to serve the people—the mass: when it fails to do that it's false to its promises: just as if a man would issue a note which from the first he has no intention of paying."

James West, who edits The New Ideal in Boston, wrote me this in a letter I received today:

"I am glad you know Whitman. When next you call on him say, perhaps, if he cares to hear, that for years I have desired to make a pilgrimage to his building. In his writings I have found as much strength, hope, inspiration for my work of teaching, as in any others I know. In the West I quoted him so often in my sermons that some shallow ones began to look on me too as 'bad.' O saving badness! O glorious weakness!"

I read this to W. who was moved. "That men, women, we never meet, have not even heard of, except in the accidental way, should respond to our work—that is a thing to be pondered. It's a waft of something, a scent, a flavor, some indefinable entity, that must not be carelessly regarded or passed by." And he said further: "This is the precious return: personal love: the precious return." Also: "John Hay in one of our talks said: 'Whitman, no man who has been so successful with the prophetic few should lament his failure with the respectable many.' And I must bear that in mind. I don't think I ever felt sore on my enemies: I rather included them as of the first importance. I was surprised to find in Emerson an occasional asperity from which I think I have been exempt: in fact the dear Emerson said to me himself there in the Astor House: 'I find you agreeably gentle with those who have been cruel to you.' And he called it—thought it—my 'policy': which I disavowed with the statement that if it was true it was rather for temperamental than conscious reasons."

Oldach takes his own time with the cover. W. ordinarily says: "I don't care: I'm in no hurry." But tonight he expressed some impatience: "I get to want to see it: Oldach is very elephantine." I said: [Begin page 5] "That's just the way he's described you: he said the other day that you were as slow as a Dutch frigate turning a corner." This made W. laugh. "God knows I'm no doubt deliberate enough: I'm so slow I get tired of my own pace: yes, he's right: but what has that to do with his own procrastination? A fellow always gets worst mad seeing his sins in other people." And he went on: "There's this excuse for me: I'm walking daily in the shadow of death: I need to hurry if I'm to get certain things done: I don't like to take any chances with time: tell the old man, yes, I'm so: but tell him I should be humored, like a convict who's to be hung tomorrow." He got a good laugh out of this for himself.

W. produced a letter from England which he spoke of to me. "Read it to me," he said: "it is from a woman: a Mary Ashley: the name has a Quakerish sound: I don't know that she's famous for anything: but that's all the better: I shrink from the celebrated and the famous: read it." So I read:

16 New King Street, Bath, England, January 7, 1889. Dear Sir:I have very often felt that I should like to write to you and tell you how much pleasure and instruction your books have given me, and now I have determined that I will do so, because I have just read November Boughs and am so much pleased with it.

I have been watching for it to be published for some time, ever since I saw in The Pall Mall Gazette that you were engaged on it. Some of the poetical pieces in it please me greatly.

I have long cared for Leaves of Grass and Specimen Days. I love nature so much myself that there is much in Specimen Days that appeals to me. I have often experienced the feeling of absorbing into myself, physically and spiritually, the very life and spirit of nature. It is a thing that must be felt to be understood. The other papers in that book are interesting to me too. The broad and deep views you take of the future of democracy in America—everything connected with America—is a most interesting study to me. Your poems touch me very deeply as all true poetry that comes from the heart must do.

Please accept my best wishes that the year we have entered upon may bring to you much calm peacefulness, and that you may experience [Begin page 6] much comfort and sympathy in return for that which you have so generously given to others during your life.

I hope you will not think that I shall expect any reply to this, for I know how weak you are, and that you are not able to reply to all the letters that you receive.

I am, my dear sir, yours very truly and gratefully, Mary Ashley.W. said: "I wonder who she is? I haven't the least idea. Take it along. I get many curious things: some adulation—a little (a little's enough): some cussing: now and then somebody goes for me—gives me hell. If I had made a collection of such documents I'd have had some queer stuff for you to preserve. Look at this for instance." He handed me the annual message of the Mayor of Brooklyn. Laughed. "Now ain't that real literature for you? I want to be generous: I'll share my possessions with you." Also gave me Bucke's letter of the 18th: "Take that too: but I don't think you'll find anything in it to excite you. Bucke's almost ready to come: that's the best news." Then: "You'll never thoroughly know, comprehend, Bucke, till you have spent a summer with him at the Asylum—on the farm: till you meet the doctors, the patients, the nurses, there: till you see Bucke at his work." Referred to Mary Ashley again. "What is there in her note to move me so? I confess it moved me. Was it something in the letter or something in me? I find myself emotionally much more readily stirred some times than others. These days I seem to need something: seem to be looking for something—feeling towards it: something my illness makes me crave: God knows what it is: something there seemed to be a hint of in the gentle Mary's letter."

I wrote Burroughs today. W. has heard from Rolleston. "He's my Irish friend," W. explained: "the real thing, I may say: well favored intellectually: fervent with native faith. There's black round the paper and envelope: I wonder who's dead? What a funny custom that is—to publish such a fact: a death in the family: insist on it: but it's going out: gone out, in fact, except with the old families—except, too, with the new families who want to cut a dash. Over there in England they take their forms seriously—observe them: all of them: from king down, from the slums up: observe them all: forms we on this side for the most part never knew or have dismissed."

[Begin page 7]What had Rolleston written? "It's not a long letter: it's about his German edition: Rolleston is anxious to have me pushed in Germany: he says I'm a German requisite—that they'll 'adopt' me. I don't flatter myself: I don't believe in requisites—in chosen people, in chosen peoples, all that—it seems quite like nonsense to me. But I acquiesce in Rolleston as a beautiful friend: yes, I do that: wonderful he is, surely: but as to the 'requisite'—well, I have no opinion on that: though as for Rolleston in the end, it's not me but the idea we stand for that he's really after: the idea: the immortal idea."

As I was leaving W. said: "I had one of the curios here for you: a letter: but it seems to have got hid away again." He rammed his fingers into several piles of stuff on the table and then dropped tiredly back in his chair. "No: I don't see it: it'll maybe show up tomorrow again: I'll not let it get away if it does: they sort of take to cover when you come"—laughing—"knowing your ruthless appetite." And he admonished me: "Keep both your eyes on the book: I'm absolutely in your keeping."