Thursday, January 24, 1889

Thursday, January 24, 1889

8 P.M. W. considerably better tonight than he had himself expected to be, he said. "Yet I do not feel very well or very ill—neither the one nor the other." "Ever since Mary's cup of coffee yesterday I have felt like myself again." Did coffee agree with him? "I can't say yes or no: Mary's cup yesterday was the first cup for two weeks: it tasted delicious: coffee carries with it decided esthetic satisfactions. Bucke has decided objections to my coffee: he includes coffee and tea with the alcoholic drinks: advises abstention altogether: believes these drinks impede or accelerate digestion—both being bad—instead of leaving it to its natural course. Bucke did not come to this conclusion bigotedly—oh no—but as a doctor, a thinking man of science, a dispassionate observer. The cause of all [Begin page 17] my woes is indigestion: Bucke realizes that—advises me accordingly: I have no doubt he is right—wholly right: he rarely talks in the air: he has no professional doctoriness: is too profound for that: which makes it natural for me to observe the precautions he suggests."

W. was reading Laurence Hutton's Literary Notes in Harper's when I entered. "Some one sent me the magazine: who could it have been?" Then he handed me the envelope. "Was it Howells?" he asked: adding: "Probably Howells' suggestion." It had come addressed to "Mr. Walter Whitman." In the Editor's Study this issue H. starts off with a section about November Boughs. W. called it "so-so" and "friendly" but didn't in the least warm up over it. "Take it along," he said: "see what you can make of it yourself." He had read some other things in the magazine. "You will find the first article very interesting in spite of its title—The Hôtel Drouot: Theodore Child." Had also read and "found very good" Verestchagin's A Russian Village: but The Work of John Ruskin by Charles Waldstein "I tried to read but found so dull I had to drop it." Frontispiece portrait of Ruskin "very vital": indeed, W. felt that "all the illustrations" were "fine, convincing, conclusive." Still, he was not "a wholesale Ruskin man": rather "take my Ruskin with some qualifications": though insisting still that Ruskin "is not to be made little of: is of unquestionable genius and nobility." He wanted to know about Waldstein, he listening to what I said as if he really wished to know. "My first feeling about Howells' piece," he said, "is wholly indifference." Then he asked: "Don't you find Howells tame? I think tame is the word: yes, tame." And he added: "He's not exactly colorless: only, he rather seems to be afraid of color."

"You know Thorndike Rice?" W. asked. "I had a note from him here today saying that he proposes having another symposium in the Review: the influence of novels on life—of English novels on American life: then he goes on to invite me to take a hand in it." "Will you do it?" "That depends: I am not at all settled in my own notions on the subject as yet." But "take the letter," he said, handing it over: "take it home: I shall not want it at once—can wait till you bring it back."

[Begin page 18] New York, January 18th, 1889. Dear Mr. Whitman:One frequently hears it said in connection with the agitation for international copyright that the enactment of the proposed law is desirable not only as a matter of justice to the foreign author, and of protection to the native, but also because the flood of English literature, especially of English fiction, which piracy lets loose sets ideals before our young readers which are contrary to the spirit of American life. I do not quite understand how the English ideal of life differs from the American, but a discussion of the subject which I propose to have in The North American Review will, no doubt, be a source of enlightenment. Will you be one of the symposium and send me your views in an article of two thousand words, or less, for which, of course, I will pay you? The American Ideal in Fiction—that will be the title; and each contributor will be expected to point out everything which he considers objectionable in the habit of reading foreign stories.

I am, dear Mr. Whitman, Allen Thorndike Rice."He is very explicit," W. said: "the letter is quite long for such a thing: he is friendly to me: I should acknowledge it in some way: but as to writing about the novelists, novels, English, American, any other—God help me: I can't see my way to it." "Have you answered the note?" "No: I want to—mean to: Rice is serious: I take him so: but what he proposes is rather out of my line." I said: "Nonsense." This stirred W. up. "Why do you say that? Nonsense? Why nonsense?" I said: "I didn't know you had a line: you speak of your line: what is your line? Ain't novels as much your line as history or anything else that's human as well as literary?" W. replied a bit testily: "You always come at me like a lawyer, shaking your fist in my face. If I say it's not in my line then it's not in my line: that's the end of it: that settles it: do you hear? that settles it." Once in a while he gets a little that way. I fired back at him: "Walt, you're guilty: you wouldn't get mad if you wasn't guilty." He still held his own. "Perhaps I would: perhaps I wouldn't: not my line: that's my say: let's stop right there." This made me stubborn too: "Walt: what in hell's the matter with you? I never knew you to fly off on so little provocation." This got at him. He quieted down at [Begin page 19] once. "It is a damned trifle, to be sure," he said: and he added: "Let's call it off." A minute later he said calmly: "Sure enough why shouldn't I write about novels too if I am of the mind to? though I hardly imagine that I shall do so in this instance."

Bucke (22d) wrote me as to The Critic review: "The piece is (as you say) 'astonishingly enthusiastic,' but its enthusiasm somehow offends me, as if it were not genuine. How is it? What is the matter with it?" I referred this to W., who said: "Yes: he wrote to the same effect to me: made the same remark about The Critic: said he liked Sanborn's column better." Gave me letter in which Bucke says: "It has a smack of unrealness, want of sincerity (but perhaps I do the writer injustice)." Had he felt such a thing himself? "Not at all: not anything that could be called even a tinge, suspicion, of it." Then he didn't agree with Bucke? "Oh no! no! I consider the objection gratuitous: have not experienced the slightest reason for such a criticism of the piece: I am even inclined to rate it above all the other things so far said of the book." W. again said: "Doctor is inclined to make impossible claims for me: he is too much disposed to wipe out the other fellows in my interest: which, of course, is an injustice to me as well as to them."

Harrison Morris writes me about W.'s "fierce" piece in The Critic. "Fierce" is Bucke's word, too. W. repeated the word "fierce—fierce," then said: "Well, what of it? If Morris was to ask me I should have to ask: Sure enough, what does it mean?" I said: "That's one way to get rid of a question, Walt: but sometimes there's another way—a better way." "Sometimes: that's so: but not this time." Then he went on half jesting, half mad: "God Almighty how I hate to be catechized!" He does, you bet. Again, upon a reference to Rice: "Not Rice—Jim Redpath was my very good friend in the Review. Redpath has been sick: is now better: has gone to Ireland: visiting, I think, somebody or other. He is a vehement Home Ruler: fiery, flaming: is an Irish sympathizer of the intensest sort." I asked W. how he stood on Home Rule. "Home Rule? I want home rule for everybody—every section: home rule: for races, persons: liberty, freedom: as little politics as possible: as little: as much goodwill, as much fraternity, as possible: that's how it presents itself to me."

W. discussed the big book. "I have turned it into all sorts of disadvantageous positions today: it always turned up well: I'll have [Begin page 20] fifty copies bound at once." Then he asked: "Isn't it dear?" and when I said "no" he added: "I guess you are right: you and Dave ought to know if anyone knows." After a slight pause: "There is an emendation—'edition 1889' must be more conspicuous: conspicuous, plain, are the two words. We want a letter that can be readily grasped as you pass the shelves." I said: "Walt: do you like the William Morris books?" He replied: "I may say yes: I may also say no: they are wonderful books, I'm told: but they are not books for the people: they are books for collectors. I want a beautiful book, too, but I want that beautiful book cheap: that is, I want it to be within the reach of the average buyer. I don't find that I'm interested in any other kind of book." I alluded to the medieval illuminated books. Didn't they appeal to him? He said: "Yes and no again: they are pathetic to me: they stand for some one's life—the labor of a whole life, all in one little book which you can hold in your hand: like the exquisite coverings I have seen brought from the East: yes, I can sense them: but they are exclusive: they are made by slaves for masters: I find myself always looking for something different: for simple things made by simple people for simple people."

I told W. that Frothingham (Octavius Brooks) would speak at the Ethical Convention tomorrow evening. "He has been very cordially my friend first and last," W. said: "I suppose he is so still: though as for that he may have shifted his point of view: they do it sometimes. I met Frothingham several years ago: talked with him: we got along together famously: he was expansive, sympathetic: he was of latitudinal longitudinal dimensions." It was curious after this that W. should have given me an old O'Connor letter in which Frothingham was alluded to. He had me read it to him.

Washington, Sept. 20, 1882. Dear Walt:I have your postals of the 3d and the 17th.

Comstock takes the dare! He cowers, like a kicked spaniel, and does not venture to carry out his threat. I thought my letter would have the effect of making him cautious.

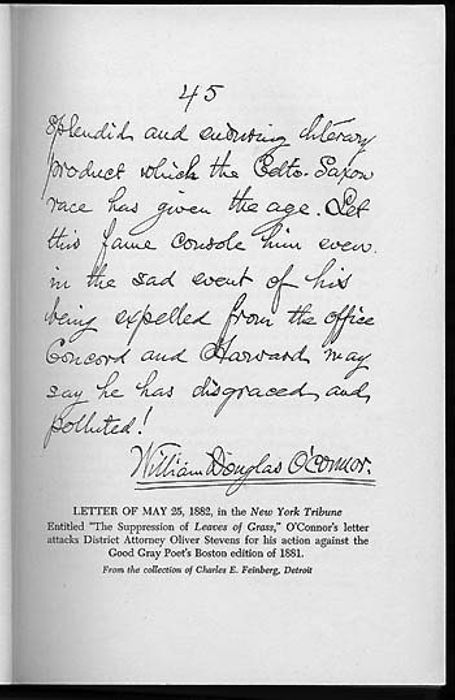

Now for Tobey. Look out for the Tribune—I have sent (last Saturday) an elaborate vivisection of the Boston postmaster and Oliver

[Begin page figure-002]

[Begin page 21] Stevens together, which, if the Tribune publishes, will certainly make a big row. I think you will like it as well as my first letter. It is gay and stinging until near the close, when it rises and darkens into righteous anger. The Boston Journal will surely respond to it, and Tobey will rue the day. Old orthodox rascal!

[Begin page 21] Stevens together, which, if the Tribune publishes, will certainly make a big row. I think you will like it as well as my first letter. It is gay and stinging until near the close, when it rises and darkens into righteous anger. The Boston Journal will surely respond to it, and Tobey will rue the day. Old orthodox rascal!

Glad to hear your other book is near the launch. I got the programme—very attractive and picturesque. I only regretted that you had included your paper on Poe, which I think all mistaken. Everyone flings a stone at poor Edgar—Stedman's the worst of all. No such man as you fancy ever got and held the love of such a woman as Helen Whitman. I know so much about him through her, and through much reading of what he wrote, that I cannot help deploring all adverse criticisms upon him.

Frothingham's article is fair, but unworthy of him. The arrière pensée is evident. He thinks better of your book than he dares to write. But such cowardice is simply shameful. A scholar ought to be a soldier, and face the batteries proudly.

I will send the Modern Thought to Bucke soon. Hurrah for Molloy! I read his article with gratification. Apropos, I wish you would tell me just what Ruskin said about L. of G., for I discover that it was to you, or some near friend of yours, that he wrote. I want to know very much.

Is there any chance of Rees Welsh printing Bucke's book? I wish it might be done. It would help, and now is the time, while public interest is alive.

I will try to get the American Queen ("spell it with an A," as I once heard Horace Mann say sarcastically) and peruse the fury.

I am glad you liked the way I cooked Comstock.

The weather here is very oppressive, and "the weight of the superincumbent hour is hard to bear, together with the load of office work and the lassitude and illness that afflict the subscriber. But October will soon be here, with healing in its wings.

My Jeannie has been very ill this summer, but is getting better, and will go to Providence on Friday. She can scarcely walk with weakness, but is on the mend. It has made life heavy for me.

Good bye. Faithfully,

William D. O'Connor. [Begin page 22]W. quoted the line: "A scholar ought to be a soldier, and face the batteries proudly." "That sounds like a call to battle: no one could do that more wonderfully than William." And he added: "In spite of what may in that incident have looked like timidity in Frothingham he has steadfastly been my friend." I said: "You and William evidently run afoul of each other over Poe." He smiled: "Yes—some: William takes a polemic interest in Poe: won't have any heresy at all with regard to him: has always made the whole demand, which I am by no means convinced of. William is a vehement expounder, propounder: won't let a fellow off with compromises, half measures." W. spoke of Comstock as "the anomaly of the age." I said: "The age supports him—allows him: how is he an anomaly?" W. assented to this. "That may be said, too: I rather suspect that we have Anthony in spite of, not because of, the age." Left at 9:30.