Thursday, May 30, 1889

Thursday, May 30, 1889

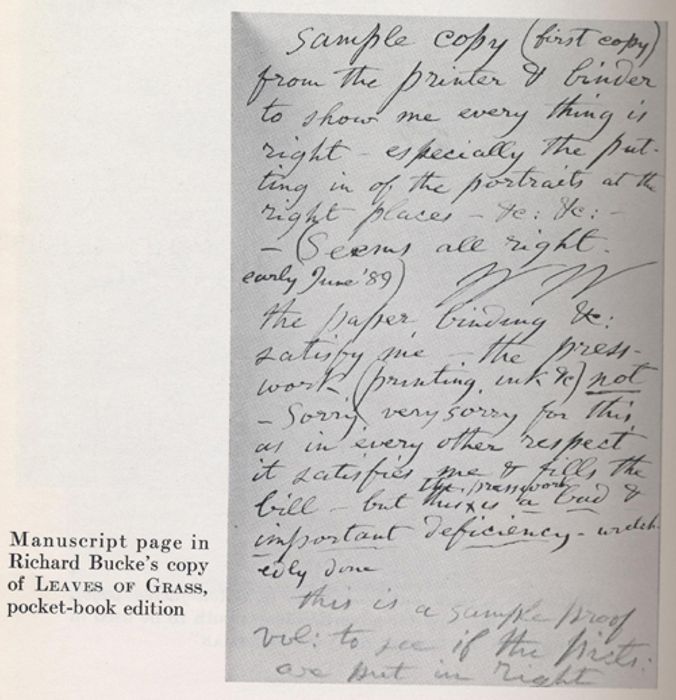

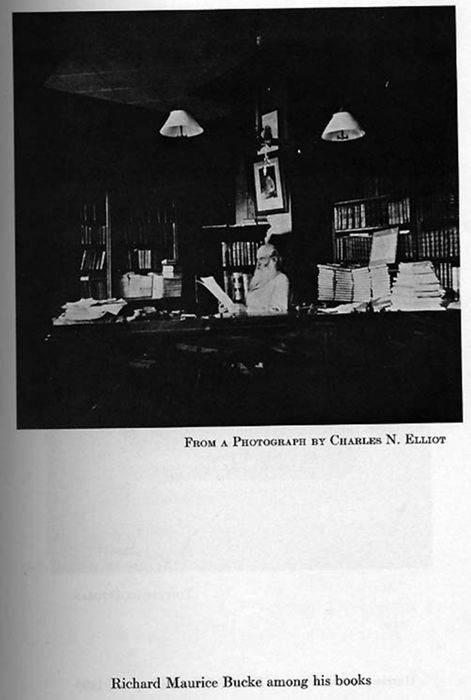

11 A.M. Just a year since the day we went down to W.'s with Kennedy and W. opened with us the bottle of Egg Harbor champagne! W. this noon, on my entrance, sat looking over a copy of the pocket edition. "I have just taken it up," he explained—"Everything seems to be right but the printing: even that is not as bad as it might be, though bad enough, to be sure. When we think of the elegant prints that come from abroad—of the English Bible—the Guild periodical—others—this makes you sick. I have tried to believe it was the paper, but can't convince myself that it is to be put off that way: it is the printer—the printer alone—who is to blame. Look at this margin! It is miserably registered." But the book as a whole impressed him. He asked me what I thought of the McKay portrait, over which he hung for a long time. "I am going to send a copy off to Dr. Bucke at once. It may be then that he will get it by the end of the week—by Saturday night. The book will, in form, be wholly new to Doctor—wholly—and that new portrait will be something for him to look at." I helped him bundle the book up. He addressed it in a large hand, and put a ten-cent stamp on it. Was that not more than was necessary? "Probably—but I always put it on that way: and look at the stamp—don't you think it a beauty? I think it the finest stamp Uncle Sam has ever issued."

W. tried to find me Edward Carpenter's letter, but it was not about, though the registered, blue-streaked envelope was at hand. W. laughingly said: "It was curious—the two letters came in the same mail—both had these same marks of registry

[Begin page 242]

—I opened Carpenter's first, and there was the money—the took up the other, expecting something substantial there, too—and lo! there was nothing but an autograph man again—the redoubtable!" Then he added: "Edward's was a very simple letter all through—very direct, very touching." And he promised: "If I receive letters that could be used for your purposes, I'll save them for you—give them to you."

"Here is one now," he went on smilingly, handing me a big envelope—"here is someone writing a poem about me—a fellow way off in the West—Milwaukee—take it away—and be sure you don't bring it again"—though adding with half compunction—"I should not like him to hear me say that—for he meant it honestly." I told him I had Elizabeth Porter Gould's poem with me: should I read it? He shook his head. Nor would he read it himself? "Neither: keep it in your pocket!" I read him Horace Howard Furness' letter, in which he was much interested. "It is Shakespearean all through"—and had me re-read the quotation. "And very kind and warm for me—perfumed." He spoke regretfully of Furness' enforced absence: "Although badly afflicted—deaf, almost utterly—he likes to get with the boys and have a jolly good time." Read him then a letter I had from Jennie Gilder this forenoon, which pleased him as being "more radical, positive, than Jo's usual manner." A third note I had this morning was from Cockrill, of the World. This, too, touched W. But most enjoyably of all did he listen to my reading of Kennedy's letter. He was intent—insisted on a second reading of good phrases, and at the end, when I called it "the best letter so far received," he nodded assent and said: "It is!—it is!—far! I do not see how it could be better." As to the excised phrase on Christianity, he laughed lightly: "It is right not to read that there: it would not be wise to open up a discussion on anything at such a moment. As men were involved in the arrangement who are very sensitive on that point, it would hardly do to raise the wind at that precise time. But you must print the letter—it must go along in the pamphlet."

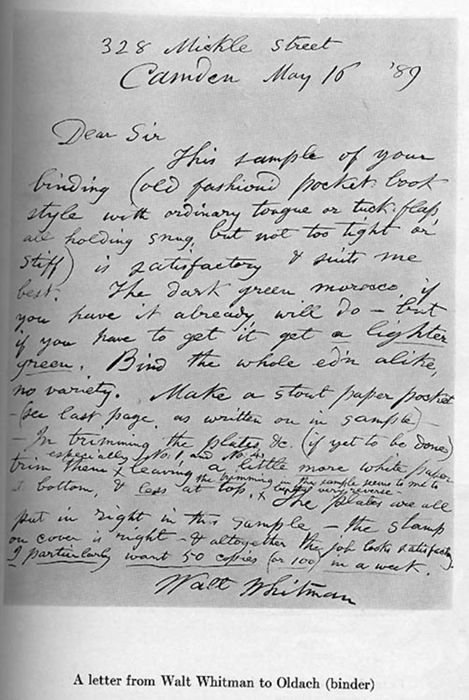

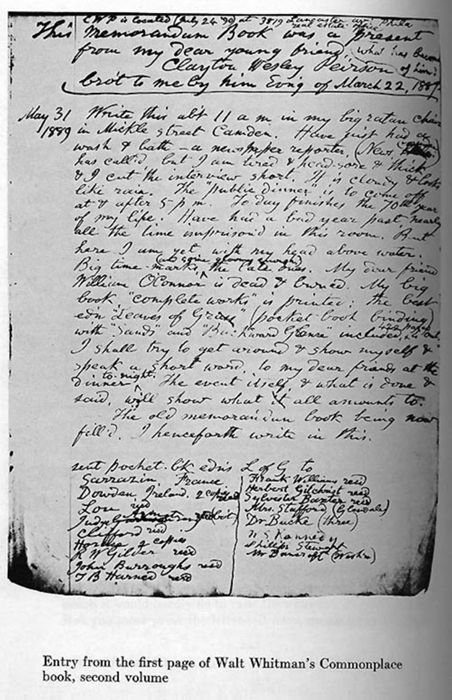

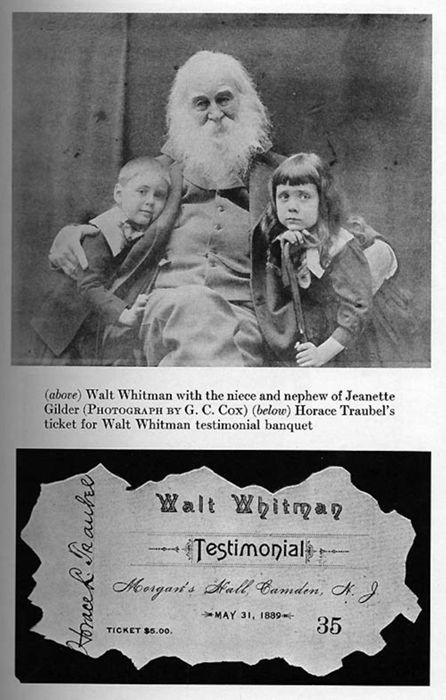

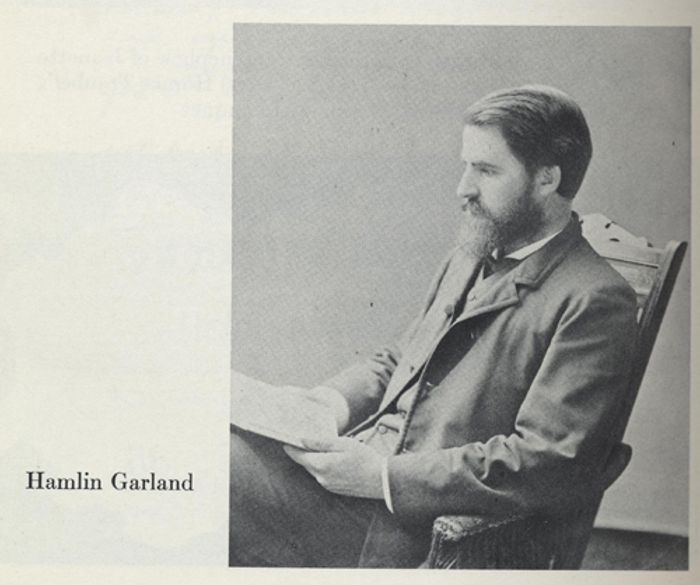

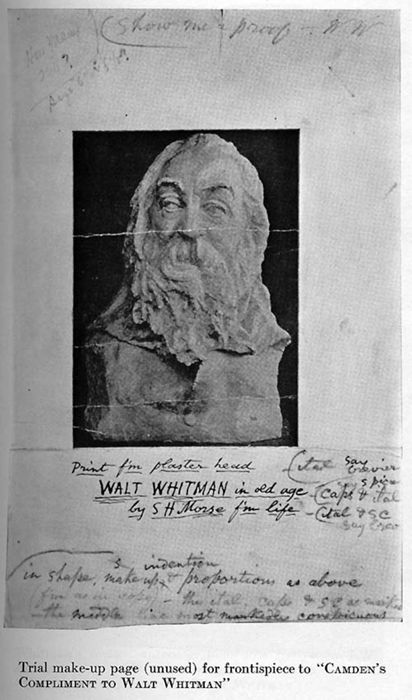

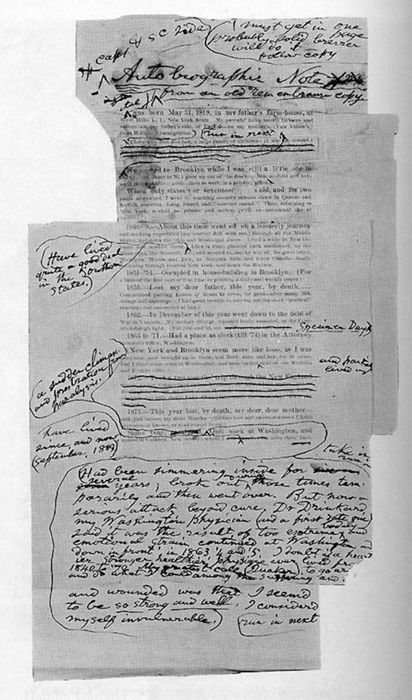

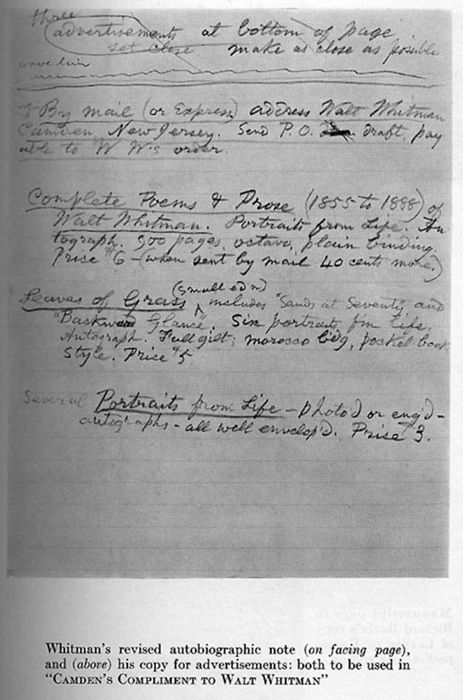

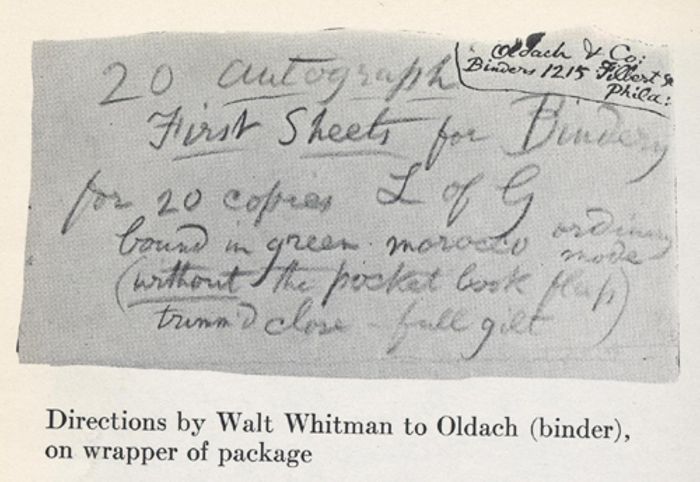

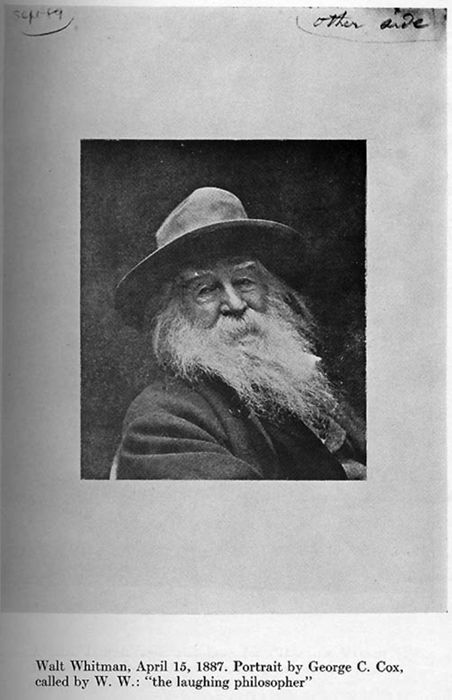

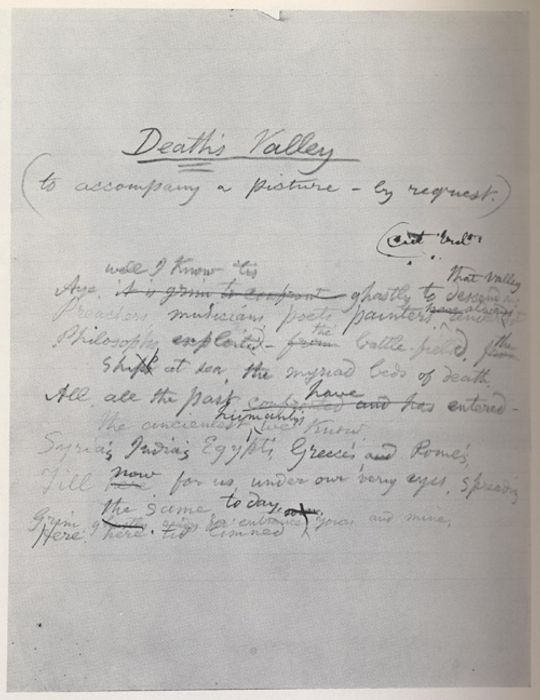

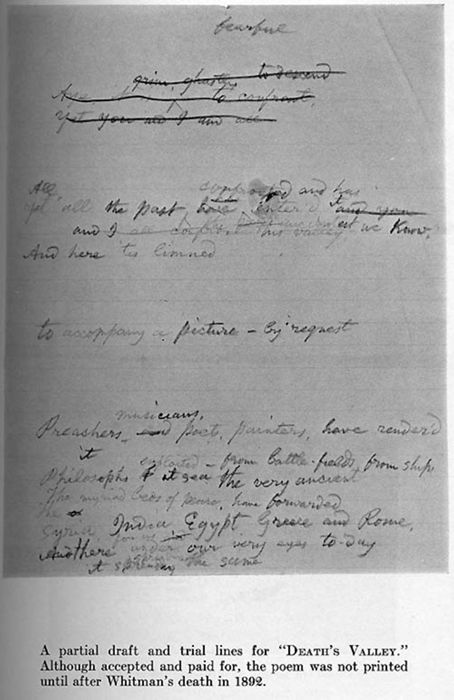

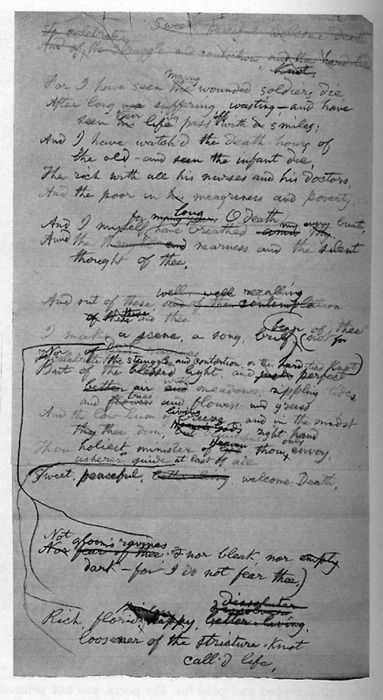

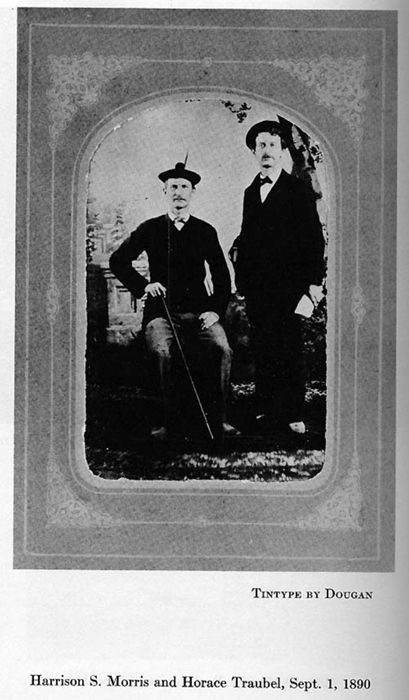

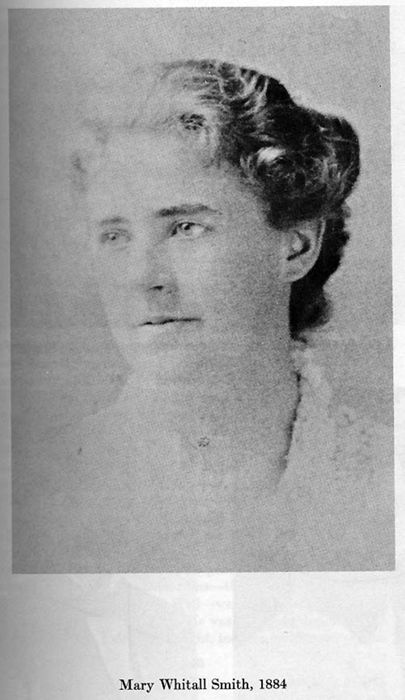

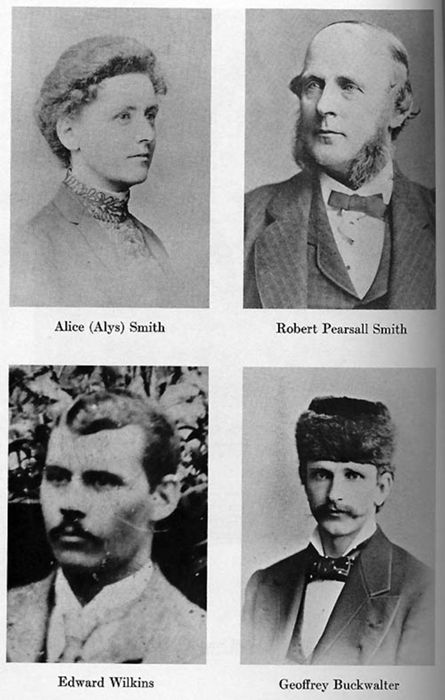

Note (): letter, dated Return to text. Note (): Commonplace book page, undated Return to text. Note (): photographs, undated, and ticket copy, dated Return to text. Note (): photograph, undated Return to text. Note (): photograph, undated Return to text. Note (): Photograph of Walt Whitman plaster head, undated Return to text. Note (): Autobiographic note, undated Return to text. Note (): Book advertisement note, undated Return to text. Note (): written binding instructions, undated Return to text. Note (): manuscript page, dated Return to text. Note (): photograph, dated Return to text. Note (): draft pages, undated, image 1 Return to text. Note (): draft pages, undated, image 2 Return to text. Note (): draft pages, undated, image 3 Return to text. Note (): photograph, undated Return to text. Note (): photograph, dated Return to text. Note (): photograph, dated Return to text. Note (): photographs, undated Return to text.

W.: "There is a thick letter down stairs from Dr. Bucke—enclosing Mrs. O'Connor's letters to him. I want you to see it: aside from its general interest it has something in about you. When you go, take it along with you. I gave it to Mary to read." W. suggested: "I think you ought to read Kennedy's letter, at least—if not others." I said I never attempted such a thing in a big hall. "Well—then now is the time to begin—read it just as you did here, only raising the pitch." "It ought to be read by somebody who knows us—who knows Kennedy."

I opened the box of books for W., and found therein 97 copies, making, with those I had brought over, and the model, 104 in all. W. joked about his pocket edition, as he had before: "The folks would always protest to me, what good are big pockets, anyhow? no one uses them? And then they would say, no gentleman carries a big book in his pocket! But I always said, I do! that is the puzzle! It seems to me that two things are indispensable in tailoring—to give a man the best buttons and provide him with plenty and strong and big pockets. I always lay this down as the law to anyone who works for me."

8.15 P.M. Found W. sitting in front of the house, the old man Curtz on the step nearby. W. said: "Ah! Horace—I was just about to go in!" So he called Ed, who responded, and between us he went laboriously into the parlor, Curtz along with us.

W. said: "I have been having your mail come to me—a couple of letters addressed here to my care—besides something of my own." He handed me a bundle of letters, four of them. One of them from Harrisburg, containing another bit of doggerel. Had he read it? "No—it got dark—I let it go." Another letter from Garland. "He is coming—he tells about it there: [Begin page 245] I am glad." The letters addressed to me were from Baxter and Sanborn. I also had a short note from Habberton this evening from Fortress Monroe, promising a note for the dinner. I read all these to W. who was much touched. He remarked of Baxter: "I count him one of my very best friends—one of the securest: his letter is fine, and very warm—perhaps too warm—not warmer, however, than was to have been expected." I read him Curtis' letter, which came to Cattell today. "Well—that is about the most positive thing that George was ever got to say, I do believe." Sanborn pleased him: I read parts of it over to him a second time. As to a telegram from J. H. Gilman, Rochester: "I don't know who he is—do you?" And he remarked in a general way: "There seems now to be a drift our way, the tide all set in for us—all for us: it makes us almost fear something, as if a disaster must be on the wind!" Spoke of his own response: "It will not be a speech or a poem—only a word or two to show I feel all that is being done for me, and shall cherish it." The old man Curtz started off on one of his long dreary monologues. W. listened patiently for a great while. I was in a hurry to get off. Suddenly I went towards W.: "Did you wish to go up stairs?" He caught the touch at a glance: "Yes—I must go." And so I helped him up and towards the door of the parlor. "I will have to say goodnight," he said to Curtz, and as we passed out into the hallway, Curtz following: "Get the labels done for me—as I said, the end of next week will do." Curtz had noticed his hasty withdrawal. "I always welcome opposing views," he protested, as if to mollify W.—who said, "Oh! I know—that is all right: only I have had a long day and must go." So Curtz, after a few more words, W. hesitating in the hallway—departed. Then W. smiled and switched off. "Let us go in to the back room here," he said, and there found Mrs. Davis and Mrs. Mapes sitting together, with whom he stayed a while. So he balked Curtz of his debate on the woman question. On his neck the gay handkerchief the Hindus had brought him: the inevitable grey hat on his head: [Begin page 246] his color good, though eye rather lustreless. "I am just back from a ride, and a good one," he explained. And said moreover: "I sent no books off today except the Doctor's—even that not till night." And he asked: "Is everything well? Buckwalter was in with what seemed a whole roll of what he called replies. It must be quite a batch. Will you get through with them all?" Spoke to Mrs. Davis: "This ceiling seems to be getting very black," adding, with a laugh, "but 'taint my funeral: if you will have it so, then have it so!" I left, having the long letters from Bater and Sanborn to transcribe. I recall this as from him: "The most significant thing about these modern pictures of Jesus is the absence of the aureola."