Visits to Walt Whitman in 1890–1891: In Camden

med_sm.00638_large.jpg

med_sm.00638_large.jpg

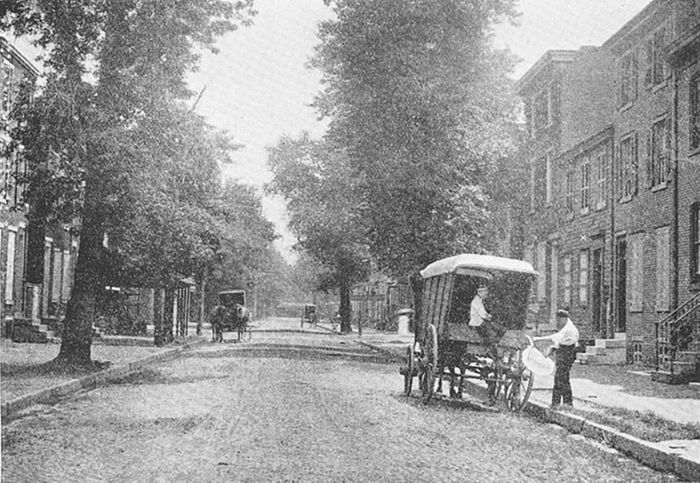

MICKLE STREET, CAMDEN, N.J. (1890).

Photograph of Mickle Street in 1890, with Whitman's house marked by an "x."

MICKLE STREET, CAMDEN, N.J. (1890).

Photograph of Mickle Street in 1890, with Whitman's house marked by an "x."

med_sm.00064_large.jpg

med_sm.00064_large.jpg

NOTES OF VISIT TO WALT WHITMAN

AND HIS FRIENDS IN

1890

IN CAMDEN

ON Tuesday, July 15, 1890, I landed at Philadelphia—"the city of brotherly love"—and after getting through the troublesome Customs I called at the post-office, where I found a letter from Mr. Andrew H. Rome, of Brooklyn, inviting me to go and stay with him, and enclosing a letter of introduction to Walt Whitman.

Crossing the ferry by the ferry-boat Delaware, I arrived at Camden, putting up at the "West Jersey" Hotel, and about noon I walked down to Mickle Street, which I found to be a quiet and retired side street, grass-grown on the roadway and side walks and ornamented with two rows of large and graceful, leafy trees, which give it quite a pleasant, breezy, semi-rural appearance. The houses are, for the most part, timbered structures, painted different, low-toned colours, and of various heights and outlines.

Number 328—which, by the way, is duplicated next door—is an

unpretentious, two-storied building, with four wooden steps to the front door,

on which is a small brass plate engraved "W. Whitman." I rang the bell, and the

vestibule door was opened by a fine young man, of whom I inquired if Walt

Whitman was at home. On his answering "Yes," I gave him my card, and was shown

into a room  med_sm.00161_large.jpg on the left side of the

lobby—a sort of parlour—with the blinds three-parts closed against

the heat.

med_sm.00161_large.jpg on the left side of the

lobby—a sort of parlour—with the blinds three-parts closed against

the heat.

The young man informed me that "Mr. Whitman was pretty well, but had been rather sick." He "Would see if he would receive me." He returned almost immediately, and asked me to "go right upstairs, turn to the left and go straight in."

I did so, and before I got to the room I heard a voice from within, calling, "Come in, Doctor! Come right in!" and in another moment I was in, and saw Walt Whitman seated. Stretching forth his right hand as far as he could reach he grasped mine with a firm, affectionate grip, saying, "Glad to see you. I've been expecting you. Sit down."

I did so, and his next words were, "And how are you?" To which I replied, and he continued, "You find it very warm in these parts, don't you? Strangers often find it uncomfortably so; but I just resign myself to it and take things quite easy; and I get along pretty well during the hot spell. So you've been travelling about our States, have you?"

"No," I said, "I only landed in Philadelphia this morning."

"Ah, I am confounding you with another friend of mine."

He talked on in the most genial, natural and affable manner for a few minutes, until I said, "But I'm forgetting my letter of introduction, and my commission."

This gave me the opportunity of changing my seat from facing the light to a place

by the window, where I could see him better. I then  med_sm.00162_large.jpg handed him Mr. Rome's letter, and while

he was reading it I took a look at him and his surroundings.

med_sm.00162_large.jpg handed him Mr. Rome's letter, and while

he was reading it I took a look at him and his surroundings.

The first thing about him that struck me was the physical immensity and magnificent proportions of the man, and, next, the picturesque majesty of his presence as a whole.

He sat quite erect in a great cane-runged chair, cross-legged, with slippers on his feet, and clad in rough, grey clothes and a shirt of pure white linen with a great wide collar edged with white lace—the shirt buttoned about midway down his breast, the big lapels of the collar thrown open, the points touching his shoulders and exposing the upper portion of his hirsute chest. He wore a vest of grey homespun, but it was unbuttoned almost to the bottom. He had no coat on, and his shirt sleeves were turned up above the elbows, exposing most beautifully shaped arms and flesh of the most delicate whiteness.

Although it was very hot he was not visibly perspiring, while I had to keep mopping my face.

His hands are large and massive, but in perfect proportion to the arms; the

fingers long, strong, and tapering to a blunt end. His nails are square, showing

about an eighth of an inch separate from the flesh. But his majesty is

concentrated in his head, which is set with leonine grace and dignity upon his

broad, square shoulders; and it is almost entirely covered with long, fine,

straggling hair, silvery and glistening, pure and white as sunlit snow, rather

thin on the top of his high, rounded crown, streaming over and around his large

but delicately shaped ears, down  med_sm.00163_large.jpg the back

of his big neck, and from his pinky-white cheeks and top lip over the lower part

of his face, right down to the middle of his chest—like a cataract of

materialized, white, glistening vapour, giving him a

most venerable and patriarchal appearance. His high massive forehead is seamed

with wrinkles. His nose is large, strong, broad and prominent, but beautifully

chiseled and proportioned, almost straight, very slightly depressed at the tip,

and with deep furrows on each side running down to the angles of the mouth. The

eyebrows are thick and shaggy with strong white hair, very highly arched and

standing a long way above the eyes, which are of a light blue with a tinge of

grey, small, rather deeply set, calm, clear, penetrating, and revealing

unfathomable depths of tenderness, kindness and sympathy. The upper eyelids

droop considerably over the eyeballs, the left rather more than the right. The

full lips are partly hidden by the thick, white moustache. The whole face

impresses one with a sense of resoluteness, strength and intellectual power, and

yet withal, it evinces a winning sweetness, unconquerable radiance, and hopeful

joyousness. His voice is highly pitched and musical, with a timbre which is astonishing in an old man. There is none of the usual

senile tremor, quaver, or shrillness, his utterance being clear, ringing, and

most sweetly musical.

med_sm.00163_large.jpg the back

of his big neck, and from his pinky-white cheeks and top lip over the lower part

of his face, right down to the middle of his chest—like a cataract of

materialized, white, glistening vapour, giving him a

most venerable and patriarchal appearance. His high massive forehead is seamed

with wrinkles. His nose is large, strong, broad and prominent, but beautifully

chiseled and proportioned, almost straight, very slightly depressed at the tip,

and with deep furrows on each side running down to the angles of the mouth. The

eyebrows are thick and shaggy with strong white hair, very highly arched and

standing a long way above the eyes, which are of a light blue with a tinge of

grey, small, rather deeply set, calm, clear, penetrating, and revealing

unfathomable depths of tenderness, kindness and sympathy. The upper eyelids

droop considerably over the eyeballs, the left rather more than the right. The

full lips are partly hidden by the thick, white moustache. The whole face

impresses one with a sense of resoluteness, strength and intellectual power, and

yet withal, it evinces a winning sweetness, unconquerable radiance, and hopeful

joyousness. His voice is highly pitched and musical, with a timbre which is astonishing in an old man. There is none of the usual

senile tremor, quaver, or shrillness, his utterance being clear, ringing, and

most sweetly musical.

But it was not in any one of these features that his charm lay so much as in his

tout ensemble and the irresistible magnetism of his

sweet, aromatic presence which seemed to exhale sanity, purity and naturalness,

and exercised over me an attraction  med_sm.00164_large.jpg

med_sm.00164_large.jpg

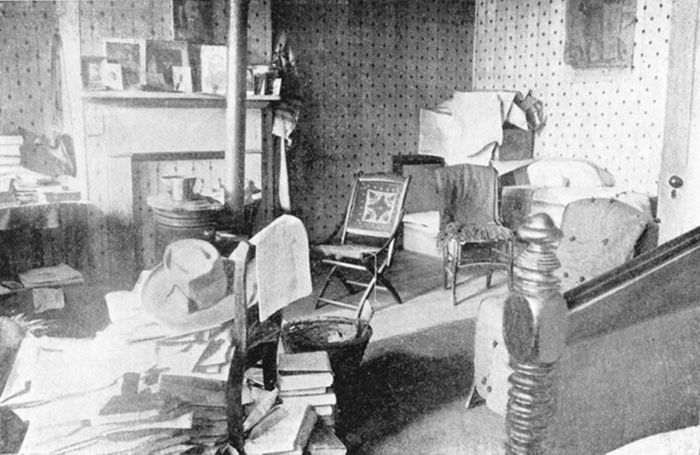

WALT WHITMAN'S ROOM (1890).

Photograph of Whitman's bedroom, showing piles of books, papers, etc.

WALT WHITMAN'S ROOM (1890).

Photograph of Whitman's bedroom, showing piles of books, papers, etc.

med_sm.00165_large.jpg which positively astonished me, producing

an exaltation of mind and soul which no man's presence ever did before. I felt

that I was here face to face with the living embodiment of all that was good,

noble and lovable in humanity.

med_sm.00165_large.jpg which positively astonished me, producing

an exaltation of mind and soul which no man's presence ever did before. I felt

that I was here face to face with the living embodiment of all that was good,

noble and lovable in humanity.

Before I refer to his talk with me, I may say a word about his surroundings, which were unique. All around him were books, manuscripts, letters, papers, magazines, parcels tied up with string, photographs and literary matériel, which were piled on the table a yard high, filled two or three waste-paper baskets, flowed over them on to the floor, beneath the table, on to and under the chairs, bed, washstand, etc., so that whenever he moved from his chair he had literally to wade through this sea of chaotic disorder and confusion. And yet it was no disorder to him, for he knew where to lay his hands upon whatever he wanted, in a few moments.

His apartment is roomy, almost square, with three windows—one blinded

up—facing the north. The boarded floor is partly carpeted, and on the east

side stands an iron stove with stove-pipe partly in the room. On the top of the

stove is a little tin mug. Opposite the stove is a large wooden bedstead, over

the head of which hang portraits of his father and mother. Near the bed, under

the blinded-up window, is the washstand—a plain wooden one, with a white

wash-jug and basin. There are two large tables in the room, one between the

stove and one of the windows, and another between that and the washstand. Both

of these are piled up with all sorts of papers, scissorings, magazines,

proof-sheets, books, etc. Some  med_sm.00166_large.jpg big boxes

and a few chairs complete the furniture. On the walls and on the mantel-piece

are pinned or tacked various pictures and photographs—Osceola, Dr. Bucke,

Professor Rudolph Schmidt, etc.

med_sm.00166_large.jpg big boxes

and a few chairs complete the furniture. On the walls and on the mantel-piece

are pinned or tacked various pictures and photographs—Osceola, Dr. Bucke,

Professor Rudolph Schmidt, etc.

He himself sits between the two unblinded windows, with his back to the stove, in the huge cane chair,¹ which was a Christmas present from the children of Mr. Donaldson, of Philadelphia.

Raising his head from Mr. Rome's letter, which he read with the air of a folding vulcanite-rimmed pince-nez, he said:—

"Oh, Doctor, you did not need an introduction to me; but I am very glad to hear from my old friend Andrew Rome. You know he was my first printer, with his other brothers, and I have a deep regard for them."

He talked so freely, and so unconstrainedly to me for over an hour, that I cannot possibly note down all that he said; and the following are mere scraps of his intensely interesting talk:—

"That must be a very nice little circle of friends you

have at Bolton." I assented; and he went on: "I

hope you will tell them how deeply sensible I am of their appreciation and

regard for me; and I should like you to tell all my friends in England whom

you come across how grateful I am, not only for their appreciation, but for

their more substantial tokens of goodwill. I have sometimes thought of

putting my acknowledgements in print in some form or other. I have already

alluded to it, but I feel it deserves more.

med_sm.00167_large.jpg I have a great many friends in

England, Scotland and Ireland, but most in England. I hope I acknowledged

your and Mr. Wallace's communications—some of my correspondents are

rather remiss, and I do not wish to be on the list of defaulters at

all."

med_sm.00167_large.jpg I have a great many friends in

England, Scotland and Ireland, but most in England. I hope I acknowledged

your and Mr. Wallace's communications—some of my correspondents are

rather remiss, and I do not wish to be on the list of defaulters at

all."

This gave me an opportunity of presenting him with the book and letter which my friend J. W. Wallace had kindly commissioned me to give him. The book was Symonds's "Introduction to the Study of Dante," and while reading the letter he exclaimed:—

"How wonderfully distinctly Mr. Wallace writes!"

"Ah, that is one of his characteristics, then. It is a pleasure to see such beautiful writing. Sometimes one has to wrestle with handwriting."

Reading on, he exclaimed, "Have you met Symonds?"

"No," I replied.

"He is a great friend of mine," he continued, "never seen, but often heard from; and he has given me a good many of his books, from time to time. He writes a good deal, and writes well; and he reads my books."

Reading the letter further on, he said, "What a wonderful

eye Mr. Wallace has for the beauties of external nature—the light, the

sky, the earth." (This was in reference to a sentence in the letter

beginning, "I draft this in the

open fields.") "That used to be a kink of mine.

'Leaves of Grass' was mainly gestated by the sea shore, on  med_sm.00168_large.jpg the west coast of Long Island, where

I was born and brought up. There is a great deal of sea there."

med_sm.00168_large.jpg the west coast of Long Island, where

I was born and brought up. There is a great deal of sea there."

I here mentioned that I purposed visiting Long Island and Huntington. "You do!" he exclaimed, evidently pleased; "then you must go to West Hills. It is a very picturesque place, and is still occupied by the same family, named Jarvis, that succeeded my father and mother in the farm. It is rather a common name there, and I think it must be a corruption of some old English name."

"Do you know Gilchrist?" he then asked.

"No," I said, "but I have an introduction to him, from Captain Nowell, of the British Prince. I believe he is staying on Long Island."

"Yes," he answered, "quite close to Huntington. He is located there, and you must go and see him."

Here I handed him J. W. Wallace's beautiful letter to me the day before my departure. As he read it, he exclaimed, "The dear fellow!" At one part of it he was visibly affected—tears standing in his eyes—and for a few moments he did not attempt to speak.

Upon my saying that I intended going to Timber Creek, he said, "That is a place I am very fond of. You must, while there, go and see Mrs. Susan Stafford, at Glendale, three miles from Timber Creek. She is a great friend of mine. Tell her that you have seen me, and that I am still, as I say, holding the fort."

On my saying that I might call on John Burroughs, he took up his big pen and

wrote out the  med_sm.00169_large.jpg address on one of his

envelopes, as well as that of Dr. Bucke, whom he suggested I should visit, if

possible.

med_sm.00169_large.jpg address on one of his

envelopes, as well as that of Dr. Bucke, whom he suggested I should visit, if

possible.

"Do you know Robert Ingersoll?" he asked me.

"Only by repute," I replied. "He was at your banquet, according to the report in the paper you sent me."

"Yes," he said, "and made a good speech of over and hour long. He lately sent me a copy of one of his books, most beautifully got up. Here it is," handing it to me, and showing me the inscription on the fly-leaf. "He is a wonderful man—one of those men who remind me of the ancient Peripatetics, who used to deliver long orations in a manner which few nowadays can. In Ingersoll there are none of the stock tricks of oratory, but it flows from him as freely as water, pure and clear from a hidden spring which eludes all the investigations of chemistry. It has spontaneity, naturalness, and yet behind it everything."

But he checked himself, saying, "I'm talking too much, and infringing on the doctor's orders; and I may have to pay for it by some little prostration."

This led him again to refer to his physical condition, which we had spoken of at the beginning of the interview.

"I am fairly well, for me, at present, though I have been sick lately. I live very simply. I had breakfast of bread and honey—there's some of the honey up there," pointing to a butter-cooler half-buried in the pile of papers on the table.

On my tasting it, he remarked, "It is in the comb, just as

the good friend who lives where the  med_sm.00170_large.jpg

bees make it sends it to me. Isn't it delicious? You can almost taste the

bees, can't you? Then I'm very fond of blackberries and fruits generally. I

have two meals a day; breakfast at half-past nine, and dinner at four

o'clock. I get out into the open air every day, if possible; my nurse [the

young man I had seen downstairs] wheels me out in the cool of the evening,

and I get along wonderfully well. My physical functions are fairly regular,

and my mental faculties are unaffected, except that they are slower than

they used to be. The brain has been somehow wounded—I don't know the

exact physical condition—I doubt if even the doctors know—but my

mentality is still as good as ever, with the exception of its being slower

than formerly."

med_sm.00170_large.jpg

bees make it sends it to me. Isn't it delicious? You can almost taste the

bees, can't you? Then I'm very fond of blackberries and fruits generally. I

have two meals a day; breakfast at half-past nine, and dinner at four

o'clock. I get out into the open air every day, if possible; my nurse [the

young man I had seen downstairs] wheels me out in the cool of the evening,

and I get along wonderfully well. My physical functions are fairly regular,

and my mental faculties are unaffected, except that they are slower than

they used to be. The brain has been somehow wounded—I don't know the

exact physical condition—I doubt if even the doctors know—but my

mentality is still as good as ever, with the exception of its being slower

than formerly."

I here referred to his paralysis.

"Yes," he said, "my right arm is my best, but I have a good deal of power in my left."

He then held it out for me to feel, which I did, and I was surprised at the wonderful softness and pliancy of the skin, and the firmness and fulness of the muscles beneath.

As I thought I had stayed long enough I rose to go, when he said: "I wish I could give you something. Have I given you my picture? I suppose so."

I replied that he had not, and, glancing around, I saw a torn scrap photograph of himself among the pile of papers and held it towards him.

"Ah," he said, "that's torn, but if you care to have it you may. I'll write my name on it."

And taking up his huge pen, he wrote on it, "Walt Whitman, July 1890."

med_sm.00171_large.jpg

med_sm.00171_large.jpg

FRONT PARLOR ON GROUND FLOOR OF WHITMAN'S HOUSE (1890).

Photograph of Whitman's bedroom, showing piles of books, papers, etc.

FRONT PARLOR ON GROUND FLOOR OF WHITMAN'S HOUSE (1890).

Photograph of Whitman's bedroom, showing piles of books, papers, etc.

med_sm.00172_large.jpg

med_sm.00172_large.jpg

Before leaving him I happened to mention my copy of "Leaves of Grass," whereupon he expressed a desire to see it, and asked me to "come again to-morrow" and show it to him, which I gladly agreed to do.

I also mentioned that I had seen a copy of the first edition of "Leaves of Grass" (the thin, quarto copy which Mr. Cuthbertson, of Annan, has), and that we were anxious to possess it.

"Why?" he asked.

"Because," I replied, "we know that the type had been partly set up by your own hand, and the book showed the first inception of your ideas."

"As to the printing," he said, "that edition was on very little different footing from the others. I always superintended, and sometimes undertook part of the work myself, as I am a printer and can use the 'stick,' you know."

Shaking hands with him, I came downstairs and was invited by Mrs. Davis, the

housekeeper, to sit down in the front room, which is less than the one upstairs

and is evidently the visitors' reception-room. The most striking thing about it

is the large collection of photographs and portraits that adorn it. Among these

I noticed oil paintings of Whitman's father, his mother, and himself. The

mantel-piece is covered with photographs, among which are those of Dr. Bucke,

the late Mrs. Gilchrist, Mr. Herbert Gilchrist, and others. Curiously enough, I

found a portrait of J. W. Wallace, and a copy of my photograph of Ecclefechan,

as well as one of myself, which we sent to him three years ago. His  med_sm.00173_large.jpg wheeled chair occupies one corner, and

his big house-chair the other. Two statuettes of ex-president Cleveland and a

huge head of Elias Hicks stand in separate corners.

med_sm.00173_large.jpg wheeled chair occupies one corner, and

his big house-chair the other. Two statuettes of ex-president Cleveland and a

huge head of Elias Hicks stand in separate corners.

In the room I found a little coloured girl, Annie Dent, "cleaning Mr. Whitman's wheeled chair," as she said. The young man who wheels him out and attends upon him, and whose name is Frederick Warren Fritzinger—"Warry," Whitman calls him—is a fine-looking young fellow with beautifully symmetrical features, coal black eyes and hair, and a quiet, unobtrusive, gentle manner. He is a genuine "sailor boy," as Whitman says. His father was a sea-captain, and he was spent a good deal of time at sea, having been round the world three times.

Mrs. Davis—Warry's foster-mother and the widow of a sailor who was drowned at sea—is an extremely pleasant and comely young "ma'am," almost typically American in face and speech, in striking contrast to Warry, who speaks without the least American accent. She has been with Whitman for six year, and Warry about three. They are both evidently very fond of him. During my stay they gave me a good deal of detailed information respecting his habits and mode of life, and were very kind to me in many ways. After chatting awhile I bade them good-day and left the house.

In the evening I had another long talk with Whitman—an unexpected treat. At

7 p.m. he was wheeled by Warry right past my hotel, according to his custom,

down to the wharf, close to the river. I was waiting about with my camera in  med_sm.00174_large.jpg

med_sm.00174_large.jpg

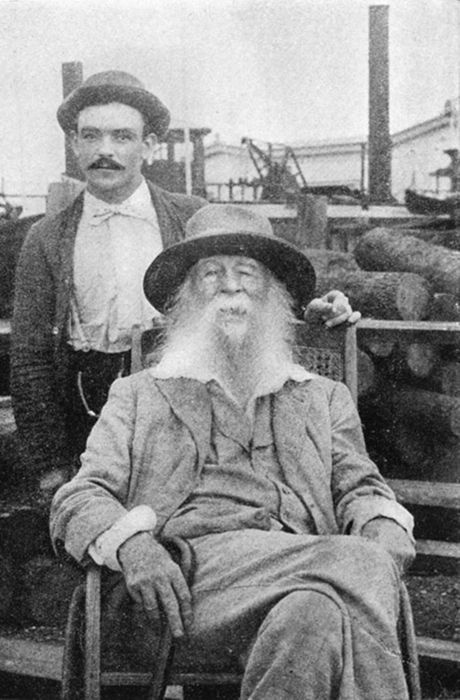

WALT WHITMAN AND WARREN FRITZINGER ON CAMDEN WHARF (1890).

Photograph of Whitman, sitting in a wheelchair, with Warren Fritzinger standing behind him.

WALT WHITMAN AND WARREN FRITZINGER ON CAMDEN WHARF (1890).

Photograph of Whitman, sitting in a wheelchair, with Warren Fritzinger standing behind him.

med_sm.00175_large.jpg the hope of meeting him, when he accosted

me, and invited me to accompany them down to the river's edge. As we approached

the wharf he exclaimed: "How delicious the air is!"

med_sm.00175_large.jpg the hope of meeting him, when he accosted

me, and invited me to accompany them down to the river's edge. As we approached

the wharf he exclaimed: "How delicious the air is!"

On the wharf he allowed me to photograph himself and Warry (it was almost dusk and the light unfavourable), after which I sat down on a log of wood beside him, and he talked in the most free and friendly manner for a full hour, facing the golden sunset, in the cool evening breeze, with the summer lightning playing around us, and the ferry-boats crossing and re-crossing the Delaware.

Soon a small crowd of boys collected on the wharf edge to fish and talk, which elicited the remark from him that—

"That miserable wretch, the mayor of this town, has forbidden the boys to bathe in the river. He thinks there is something objectionable in their stripping off their clothes and jumping into the water!"

In reference to these same boys he afterwards remarked:—

"Have you noticed what fine boys the American boys are? Their distinguishing feature is their good-naturedness and good temper with each other. You never hear them quarrel, nor even get to high words. Given a chance, they would develop the heroic and manly; but they will be spoiled by civilization, religion and the damnable conventions. Their parents will want them to grow up genteel—everybody wants to be genteel in America—and thus their heroic qualities will be simply crushed out of them."

During the talk which followed, and referring  med_sm.00176_large.jpg to his services during the War, he said that the memories of the American

people were "very evanescent."

"I daresay you find the same thing in

England"—this without the slightest tinge of resentment or ill-feeling

in his words; in fact, I never heard him express an angry feeling except when he

referred to the mayor's action in reference to the boys, and to the influences

which he knew would spoil them for men.

med_sm.00176_large.jpg to his services during the War, he said that the memories of the American

people were "very evanescent."

"I daresay you find the same thing in

England"—this without the slightest tinge of resentment or ill-feeling

in his words; in fact, I never heard him express an angry feeling except when he

referred to the mayor's action in reference to the boys, and to the influences

which he knew would spoil them for men.

The great hope of the America of the future, he said, lies in the fact that fully four-fifths of her territory is agricultural, and must be so; and while in towns and cities there is a great deal of pretentious show, sham and scum, the whole country shows a splendid average, which is an absolute justification for his fondest hopes—and nothing could ever destroy. All his experiences of the War confirmed him in it, and it was yet destined to find its full fruition in the future.

He quoted the saying of the Northern Farmer of "Lord Tennyson" as he called him: "Taake my word for it, Sammy, the poor in a loomp is bad"; which he took exception to, saying that the poor in a lump were not bad. "And not so poor either; for no man can become truly heroic who is really poor. He must have food, clothing and shelter, and," he added significantly, "a little money in the bank too, I think."

"America's present duty," he continued, "was to develop her material sources for a good many

years to come, and to trust that the spirit of the men who fought as those

soldiers did [in the War of Secession] would yet prove itself and justify

our most sanguine hopes." He repeated, almost  med_sm.00177_large.jpg verbatim, the "Interviewer's Item" in

"Specimen Days," the gist of which is that it is the business of the Americans

"to lay the foundations of a great nation in products,

in agriculture, in commerce," etc., and "when

these have their results and get settled, then a literature worthy of us

will be defined." Unlike other lands, the "superiority and vitality" of the nation lie not in a class—a

few, the gentry—but in the bulk of the people. "Our

leading men," he says, "are not of much account,

and never have been, but the average of the people is immense, beyond all

history." In the future, he thinks, "we shall not

have great individuals or great leaders, but a great average bulk,

unprecedentedly great."

med_sm.00177_large.jpg verbatim, the "Interviewer's Item" in

"Specimen Days," the gist of which is that it is the business of the Americans

"to lay the foundations of a great nation in products,

in agriculture, in commerce," etc., and "when

these have their results and get settled, then a literature worthy of us

will be defined." Unlike other lands, the "superiority and vitality" of the nation lie not in a class—a

few, the gentry—but in the bulk of the people. "Our

leading men," he says, "are not of much account,

and never have been, but the average of the people is immense, beyond all

history." In the future, he thinks, "we shall not

have great individuals or great leaders, but a great average bulk,

unprecedentedly great."

Speaking again of the War, he said that the surgeons, with whom he mixed a good deal, proved themselves heroic in their struggles to save the lives of the soldiers of both sides. "My sympathies," he said, "were aroused to their utmost pitch, and I found that mine were equaled by the doctors'. Oh, how they did work and wrestle with death! There is an impression that the medical profession in war time is a bit of a fraud, but my experience contradicts this; and nothing can ever diminish my admiration for our heroic doctors." I remarked that he had not put this in his book so emphatically, to which he said that he knew he had not, but felt that he ought to do, and if opportunity offered he intended doing so.

O'Connor and he, with a few others "who," he said, "must have been something like your little band in

Bolton," were among the few in Washington who supported Lincoln in his

policy. "We  med_sm.00178_large.jpg are

ready enough to shout hurrah for him now; but I tell you that up to his

death he had some very bitter enemies."

med_sm.00178_large.jpg are

ready enough to shout hurrah for him now; but I tell you that up to his

death he had some very bitter enemies."

"There were times, too, when the fate of the States trembled in the balance—when many of us feared that our Constitution was about to be smashed like a china plate. But it survived the conflict. We won, and it was wonderful how we did win."

Referring to Warren as his "sailor boy," he said that he had been of great service to him when he was at a loss about the names, etc., of parts of a ship. It had always been his custom, when writing or describing anything, to seek information directly from the men themselves; and he gave me two illustrations of this.

1. In one edition of "Leaves of Grass" he wrote, "Where the sea-whale swims with her calves," because he had often heard sailors say that the calves did swim with the mother; but on reading it to an old whaler he was told that it was a very exceptional thing for a whale to have more than one calf; so he altered it to—"Where the sea-whale swims with her calf." (See "Leaves of Grass," p. 56.)

2. He was under the impression that the Canadian raftsmen used a bugle, and he referred to it in one of his lines; but when he went to Canada he found his mistake and struck it out in the next edition.

Speaking of Walter Scott's edition of "Leaves of Grass," he said he did not like

it. "It was like cutting a leg, or a shoulder, or the head

off a man, and saying that was the man." He pre  med_sm.00179_large.jpg

med_sm.00179_large.jpg

WALT WHITMAN'S HOUSE (1890).

Photograph of Whitman's house, taken from the street.

WALT WHITMAN'S HOUSE (1890).

Photograph of Whitman's house, taken from the street.

med_sm.00180_large.jpg ferred that people who wished to read him

should have the whole critter, and those parts of his

book to which so many took exception were the very ones that he regarded as most

indispensable.

med_sm.00180_large.jpg ferred that people who wished to read him

should have the whole critter, and those parts of his

book to which so many took exception were the very ones that he regarded as most

indispensable.

"Voltaire," he said, "thought that a man-of-war and the grand opera were the crowning triumphs of civilization; but if he were living now he would find others more striking—in the modern development of engineering, etc."

"A ship in full sail is the grandest sight in the world, and it has never yet been put into a poem. The man who does it will achieve a wonderful work." "I once cherished the desire," he continued, "of going to sea, so that I might learn all about a ship. At another I wished to go on the railway to learn the modern locomotive. The latter I did to some extent, but the former I did not."

I asked him where I could get a copy of Dr. Bucke's "Man's Moral Nature." He told me at Mackay's, Philadelphia; and on my asking whether I could get a copy of John Burrough's "Notes" there also, he said, "Oh, I will give you a copy of that, if you like. I think I have one I can spare."

After listening to his delightful talk—(oh, that I could reproduce his

words, and, more than all, the sweetness of his voice, the loving sympathy, the

touches of humour, the smile that played round the lips

and in his merry twinkling eyes, the laughter that shook his stalwart frame, and

the intense magnetism of his personal presence!)—we returned, I

accompanying him right to his own door in Mickle Street. He talked the whole

time, seemed  med_sm.00181_large.jpg pleased with everything and

everybody; and everyone—man, woman and child—seemed to like him. He

saluted nearly every person he passed—the car drivers he accosted by name;

to the young men, he said "How do, boys?"; to the

women sitting on the door steps, with babies in their arms, he said, "How do, friends, how do? Hillo,

baby!" The labourers loafing at the corners

saluted him with: "Good evening, Mr. Whitman!" and some took off their hats to

him, though most simply bowed respectfully.

med_sm.00181_large.jpg pleased with everything and

everybody; and everyone—man, woman and child—seemed to like him. He

saluted nearly every person he passed—the car drivers he accosted by name;

to the young men, he said "How do, boys?"; to the

women sitting on the door steps, with babies in their arms, he said, "How do, friends, how do? Hillo,

baby!" The labourers loafing at the corners

saluted him with: "Good evening, Mr. Whitman!" and some took off their hats to

him, though most simply bowed respectfully.

As he went along he told me that he had "sent off a card to Wallace"; and continued, "When you see him tell him what a pleasure it is for me to see his beautiful caligraphy. I get so many letters that I can only read with a struggle, that I cannot help stopping to admire one which is well written. I am very fond of a well-printed book. Your William Black & Sons, of Edinburgh, produce some splendidly printed works. I think I was intended for an artist; I cannot help stopping to look at the 'how it's done' of any piece of work, be it a picture, speech, music, or what not."

"Ingersoll is a good illustration of what I mean. From my point of view the main question about his matter is 'What does it amount to?' But I cannot but admire his manner of giving it utterance—it is so thoroughly natural and spontaneous—just like a stream of pure water, issuing we know not whence, and flowing along we care not how, only conscious of the fact that it is beautiful all the time."

Soon we reached his house, where Warren  med_sm.00182_large.jpg

"scotched" his chair in the angle between the steps and the wall. He invited me

to take a seat beside him, on the steps, which I did, and he talked off and on

for half-an-hour longer, mostly about his health and physical condition. He

allowed me to feel his pulse, which I was pleased to note was fairly full and

strong, and quite regular—no intermission, as I half expected. Upon my

expressing the hope that he would not feel any ill after-effects from to-day, he

said—

med_sm.00182_large.jpg

"scotched" his chair in the angle between the steps and the wall. He invited me

to take a seat beside him, on the steps, which I did, and he talked off and on

for half-an-hour longer, mostly about his health and physical condition. He

allowed me to feel his pulse, which I was pleased to note was fairly full and

strong, and quite regular—no intermission, as I half expected. Upon my

expressing the hope that he would not feel any ill after-effects from to-day, he

said—

"No, Doctor, I don't think so—though I have had a quite a number of visitors. A dear niece (my brother's daughter) came to see me, after a considerable interval, and I have had several others as well as yourself, Doctor. It has been quite a 'field day' with me. My doctor is very strict, but I am always fearful of being too good, you know, and I am often tempted to trespass." He then told me the following story:—

An old gentleman, named Gore, lived opposite to him (in Mickle Street), who was so strictly proper in all his ways that once, when ill, he asked the doctor so many questions about what he must eat, drink, and avoid, that the doctor told him the best thing for him would be to go on a "devil of a drunk"! "By which," said Whitman, "I guess he meant that he lived so strictly by rules that it would be best for him to break through and away from them all for once. And," he added, with a chuckle, "I sometimes feel that way myself!"

"I suppose after this I shall have what Oliver Wendell

Holmes calls 'a large poultice of silence.' Holmes is a clever fellow, but

he is  med_sm.00183_large.jpg too smart, too cute, too

epigrammatic, to be a true poet."

med_sm.00183_large.jpg too smart, too cute, too

epigrammatic, to be a true poet."

"Emerson came nigh being our greatest man; in fact, I think he is our greatest man."

Some people passing and saluting him, I said, "You seem to have lots of friends about you, Mr. Whitman."

"Yes," he replied, "and I have some very bitter enemies. The old Devil has not gone from the earth without leaving some of his emissaries behind him."

He then referred to the lines he wrote—at the request of an editor—upon the death of the old German Emperor, and said that his Democratic and Liberal friends were incensed at him for venturing to say a word in his favour.¹¹

"You know, I include Kings, Queens, Emperors, Nobles, Barons and the aristocracy generally, in my net—excluding nobody and nothing human—and this does not seem to be relished by these narrow-minded folks."

"I had a visit last year from a young English earl, who, in the course of conversation, said:—

"'I have an impression that you regard lords and nobles as akin to fools.'

med_sm.00184_large.jpg

med_sm.00184_large.jpg

"'Well,' I replied, 'there is an impression of that kind abroad.'

"'But,' said the earl, 'I venture to hope that you may be willing to admit that there may be exceptions—that they are not all alike!'

"Which I thought," said Whitman, "a remarkably good answer."

As it was not 9 p.m. (his bedtime), I bade him good-night and went to my hotel, pondering deeply on many things, and marveling at the wondrous magnetic attraction this man had for me—for I felt I could stay with him for ever.

—A magnificent day, but so intensely hot that movement of any kind is

almost impossible. It had been my intention to go to Timber Creek to-day; but

finding, on inquiry, that it is not very easy of access, I decided to spend the

time at 328 Mickle Street. And now I am glad, because I have been able to take

photographs of the house and its inmates, and have held much pleasant converse

with them. Mrs. Davis gave me an engraved portrait of Whitman, and expressed a

great desire to send something as a little present to my wife. She is an

altogether agreeable person, and so charmingly natural that I do not wonder at

Whitman liking her; while Warren is so gentle, so unassuming, frank, intelligent

and unaffectedly kind-hearted that the more I see of him the better I like him.

He and I had a walk together, during which he talked about Whitman. He said that

two years ago the doctors—including Dr. Bucke, who was in

attendance—all said that he could not live, but that he  med_sm.00185_large.jpg is better now than he was for a long time

after that. He always attends to his mail himself, and replies with his own hand

to all his letters, except those of autograph-hunters, which are consigned to

the waste-paper baskets.

med_sm.00185_large.jpg is better now than he was for a long time

after that. He always attends to his mail himself, and replies with his own hand

to all his letters, except those of autograph-hunters, which are consigned to

the waste-paper baskets.

But my good fortune did not end here, for I was favoured with another brief interview with Whitman himself, whom I found lying upon his bed (over the head of which hangs a large daguerreotype of his mother—another of his father hanging by the washstand—), fanning himself—prostrated by the intense heat. I took the fan and fanned him for about five minutes, when he said:—

"I have found that copy of John Burroughs's 'Notes,' and I will get up and give it to you."

I assisted him on to his feet; and with his right arm round my neck and my left round his waist we walked across the floor to his chair, wading through the sea of papers on our way.

He then gave me John Burroughs's little book, and taking up two other booklets, he said,—

"I wish you to give these to Mr. Wallace, and these"—(taking up two similar ones)—"are for yourself."

They were copies of "Passage to India" (1871) and "As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free" (1872).

I thanked him, and afterwards, at my request, he kindly wrote our names and his own on the title pages of them all.

As I did not want him to talk much, I showed him some of my photographs. One of Annan, from the Milnfield, he especially admire, saying—

"What a beautiful vignette! There's nothing finer. It is very pretty."

med_sm.00186_large.jpg

med_sm.00186_large.jpg

He looked at it with evident interest for several minutes, and though I had intended it for John Burroughs I gave it to him.

He was interested in my copies of "Leaves of Grass" and "Specimen Days" (Wilson and McCormick's), which he had not seen before, but he at once recognized the type, and said,—

"I see they have used our type and their own title page. I believe they had permission to do so."

When shown the photograph of the interior of "Eagle Street College," he exclaimed,—

"So this is the room where you good fellows all meet! What a beautiful room!"

I asked him if he recognized the portrait on the wall.

"Is it mine?" he asked eagerly; "which one is it?"

I told him that it was published in the Illustrated London News, when he said,—

"Oh, I have seen it—and I don't like it."

"Why?" I asked.

"A friend of mine says there's a foxy, leering, half-cynical look about it—and I think he's right," he replied. "It's a wonderfully good piece of engraving, though," he added.

I gave him a photo of J. W. Wallace's room, as well as those of J. W. W. himself, which I took there.

He referred to our hour on the wharf last night, with evident pleasure.

Soon rising to go, I said, "Is that the portrait of Osceola?" referring to an old tattered engraving tacked on the wall near the door.

med_sm.00187_large.jpg

med_sm.00187_large.jpg

"Yes," he replied; "do you know much about him?"

"Not much," I said. He then gave me a brief sketch of Osceola's history—telling me that he was a Seminole chief whose grandfather was a Scotsman, married to an Indian squaw, down Florida way, and when trouble broke out some fifty years ago he was basely betrayed, imprisoned and literally done to death.

"That portrait," he continued, "is by George Cable, who is quite a clever portrait engraver. I got it in Washington during the war. It was packed away for a good many years, and when I found it it was all torn, cracked and frayed. I spent an hour one day in piecing it and pasting it on the paper."

Among the photographs on the mantel-piece upstairs I noted the original of the engraving in my edition of "Leaves of Grass," two of Prof. Rudolph Schmidt, of Copenhagen, one of Dr. Bucke, and others.

"And that," I said, pointing to a picture behind a pile of papers, "is another oil painting of yourself?"

"Yes," he said; "do you like it?"

"I do," I replied hesitatingly.

"Then you may take it with you if you like; I don't care for it," he said. "It was done several years ago by Sidney Morse, but I don't think it is satisfactory."

"Nor do I. In fact, I've never yet seen a portrait of you that is quite satisfactory to my mind," I said. "They are portraits, but they are not you."

med_sm.00188_large.jpg

med_sm.00188_large.jpg

"No, I guess not," he said. "You cannot put a person on to canvas—you cannot paint vitality."¹

Before my leaving he again referred to his circumstances, saying that he got along pretty well. The time of his extreme poverty had gone. He had many good friends, his wants were few, "and," he added, but without the least touch of sadness, "it will probably not be for very long that I shall want anything. I have no desire to emulate the manners of the genteel; and I never was one to whom so-called refinement, or even orderliness, stood for much."

Fearing that I had trespassed too much on his time, and feeling overwhelmed by his generosity, I took my leave.

On the mantel-piece of the room downstairs I found the photograph of "The Boys of the Eagle Street College," as well as those of Carlyle's grave and birth-room, which we had sent to him.

In the evening, I walked down to the wharf, in hopes of seeing Whitman and

"Warry," but was disappointed. I sat down on a log, and ate my repast of fruit

and crackers. Near me were a good many boys, of the lower middle class, fishing

and frolicking, and I could not but remark the genuine good humour that prevailed among them, and the entire absence of anything

approaching to rudeness or bad language; joking, of course, there was, but all

in good-natured fun, and I never

med_sm.00189_large.jpg heard a

single unseemly utterance. I think our English boys of a similar class would

compare very unfavourably with them. Nurses, with

babies and little children, were sitting about the logs, and I enticed one

bright little boy of three-and-a-half years on to my knee with my bag of

crackers. The sun had set beyond the river, and in its afterglow Venus was

outshining mildly and unattended. I stayed there, in the waning light, enjoying

the cool breeze from the Delaware—until the mosquitoes drove me home.

med_sm.00189_large.jpg heard a

single unseemly utterance. I think our English boys of a similar class would

compare very unfavourably with them. Nurses, with

babies and little children, were sitting about the logs, and I enticed one

bright little boy of three-and-a-half years on to my knee with my bag of

crackers. The sun had set beyond the river, and in its afterglow Venus was

outshining mildly and unattended. I stayed there, in the waning light, enjoying

the cool breeze from the Delaware—until the mosquitoes drove me home.

—Another day of magnificent sunshine and intense heat.

I crossed the Delaware in the Weenonah—Whitman's old favourite ferry-boat, he told me the other night, while we were sitting together on the wharf—the name of an old Indian tribe, though probably a corrupt spelling.

Returning, I took a bag of fruit with me to Mickle Street, and received a most cordial welcome from Whitman, who was seated in his chair fanning himself, looking quite bright and happy, dressed as on the first visit, and spotlessly clean. He gave me his manly grip with extended arm, saying—

"How do, Doctor, how do? Take a seat"—pointing to a chair. He said he had had a fairly good night, and had partaken of his usual breakfast of bread and honey (with milk and iced water, I think).

In a few minutes he said, "I'm going to send this

photograph to Wallace"—lifting up a large mounted photograph from

the top of his pile of  med_sm.00190_large.jpg papers—"I wish him to substitute it for the one he has hanging

in his room, as I don't like that one at all. It makes me look, as I told

you, a bit foxy, sly, smart, cute and almost Yankee. So if you will take

this one, and ask him to put it in place of the other, I shall be glad. If

it doesn't quite fit the frame you can get what we call a mat—I dare

say you in England have them—and make it fit."

med_sm.00190_large.jpg papers—"I wish him to substitute it for the one he has hanging

in his room, as I don't like that one at all. It makes me look, as I told

you, a bit foxy, sly, smart, cute and almost Yankee. So if you will take

this one, and ask him to put it in place of the other, I shall be glad. If

it doesn't quite fit the frame you can get what we call a mat—I dare

say you in England have them—and make it fit."

I said that Wallace would value this photograph very highly indeed, and I considered it the very best one of him I had yet seen.

"Yes," he said, "I think it is pretty satisfactory myself. They got me over in Philadelphia, much against my inclination, in the spring, I think it was, and that is the result of my sitting. Nowadays photographers have a trick of what they call 'touching up' their work—smoothing out the irregularities, wrinkles, and what they consider defects in a person's face—but, at my special request, that has not been interfered with in any way, and, on the whole, I consider it a good picture. And now I'll write my name on it, and I want you to take it to Wallace with my love." He then wrote on it, "Walt Whitman in 1890."

I told him I should try to coy it.

"Oh!" he said. "Well, if you do, I should be glad if you would send me a copy." This I promised to do.¹

I now produced my bag of fruit and gave him an orange, which he at once put to his nostrils, saying, "How delicious it smells!"

med_sm.00191_large.jpg

med_sm.00191_large.jpg

He smelled it in silence three or four times, each time dwelling upon it, and taking long, deep inspirations, closing his eyes and being apparently lost to everything except the delicious feeling which the aroma of the luscious fruit imparted to him. I noticed that he did not do this with any fruit except the orange, and that grapes, peaches and pears were admired and commented on, but no so lovingly handled as the orange, which he again took up and smelled after putting all the others aside.¹

He then took up a little volume—"Camden's Compliment to Walt Whitman"—saying, "Oh, I've found a copy of that little book I spoke of the other day, and will give it to you since you say you've not seen it."

Now it so happened that I had bought a copy at David Mackay's, and I told him so; but I said that since it was his original intention to give it to me, I would accept it and give mine to someone else. He thereon wrote in it, "J. Johnston, from Walt Whitman, July, 1890."

I afterwards found that he had put the following not on page 53, by the side of

Rudolph Schmidt's letter—"This is the

letter of R. S., referred to

med_sm.00192_large.jpg by me

when Dr. J. asked about the photo in Mickle Street."

med_sm.00192_large.jpg by me

when Dr. J. asked about the photo in Mickle Street."

Speaking of David Mackay, I mentioned the fact of his being a Scotsman, when he said that he had known quite a number of Scotsmen—"dozens, scores of them"—and had a high admiration for them. There was something "very human," something "very good and attachable," in the Scottish people, especially in the mothers of large families. Scotsmen, he thought, were apt to be a little glum and morose, as Carlyle was, but as they became old they usually mellowed a good deal.

I told him I had got an autograph copy of "Peter Peppercorn's" poems, and he said he was glad I had, because he knew "Peter" very well, and liked him for his genuine goodness of heart and his sharpness of intellect which was almost uncanny. He was a Scotsman, or of Scottish extraction; sometimes came to Camden to see him; and, with all his faults, was a downright good fellow.

Another volume I had was "Poems by Hermes" (Thayer), the author of which he also knew. "He comes here," he said, "and is a fine fellow—in fact, a very handsome fellow. I believe he is writing a history of modern Italy, including Garibaldi and his times."

He afterwards most willingly consented to let me try to take a photograph of the interior of his room, which I did, but he said,—

"You can't do it, Doctor, no more than you can photograph a bird. You may get an outline of the bird's body, but you can't fix the life, the surrounding air, the flowers and the grass."

med_sm.00193_large.jpg

med_sm.00193_large.jpg

On my leaving, he shook hands very warmly with me, saying,—

"Good-bye, Doctor, good-bye! Give my love to Wallace and the rest of the fellows—and tell them that I hope they won't overestimate Walt Whitman. He doesn't set up to be a finished anything, but just a rough epitome of some of the things in America. I have always been glad to hear from you all, and now that I have seen you in propriâ persona I feel that I know you, and regard you as friends. Good-bye, good-bye!"

Coming downstairs, I was invited by Mrs. Davis to join them in their mid-day repast, which I did; and much did I enjoy the sugared blackberries, bread and butter, and coffee. In fact, I regard it as almost the crowning honour that I should be asked to share the hospitality of Whitman's house, and to sit in that quaint, ship's-cabin-like kitchen, as one of the family.

Mrs. Davis gave me a fan which "Mr. Whitman" used for some time, and had given to her; also a bottle of most beautiful shells (off the mantel-piece), which her late husband had brought from the Island of Cuba. These are presents from Mrs. Davis to my wife.

Another member of the household is Harry Fritzinger—"Warry's" brother—a fine, tall, handsome young American, quiet and reserved in manner, but very likeable, and evidently "a good sort."

The other inmates are Polly the robin, Watch the spotted dog, a parrot, Kitty the black cat, and a canary bird.¹

While sitting there I was surprised to hear Whitman coming downstairs, "all by himself"; and he actually got nearly to the bottom before Warren could reach him. When he was seated in the front room he asked:—

"Has the Doctor gone?"

"No sir," answered Warren; "he's having a cup of coffee and some blackberries in the kitchen."

"Oh," said Whitman, "I'm very glad, and I hope he'll enjoy them."

We overheard him tell Mrs. Davis that he had sent a poor woman a dollar, and she had just replied, saying that she had "received his gift," which wording did not please him, for he said,—

"Why can't she say that she has received the dollar I sent, and not go running the devil round the post by saying that she has received my gift?"

I then came into the room for my things, and on my saying "Good-bye" again to him, he held out his hand—this time the left one, simply because it seemed to be the handiest at the moment.

Warren came with me to my hotel, assisted me to pack my box, put it on to the hack, went with me to the station, and even accompanied me in the train to the first station out. In our talk he said that he though Mr. Whitman had enjoyed my coming to see him, and he had never heard him say anything but what was pleasant in reference to it.

Many of his visitors, he said, seemed to expect

med_sm.00195_large.jpg him to keep talking about "Shakespeare and poetry" and such-like, all the time;

and Mr. Whitman told him that he liked a little of the talk of everyday life

occasionally—in fact, as Mr. Whitman once put it, he "liked to be a sensible man sometimes!"

med_sm.00195_large.jpg him to keep talking about "Shakespeare and poetry" and such-like, all the time;

and Mr. Whitman told him that he liked a little of the talk of everyday life

occasionally—in fact, as Mr. Whitman once put it, he "liked to be a sensible man sometimes!"

The following additional notes may be of interest:—

He does not use tobacco. I should be surprised if he did; I could not imagine Walt Whitman smoking.

He does not use a table for writing, but does it on a pad upon his knee; and he writes slowly and deliberately, but without the least perceptible tremor. He uses a huge penholder and pen, and he seldom blots his writing, preferring to let the ink dry.

He speaks slowly, distinctly, and with forceful and telling emphasis, occasionally hesitating for the right word or expression, but always rounding and completing his sentences in his own way; and I noticed that he frequently made use of phrases and words familiar to me in his books.

Of late years he seems to have changed in two particulars. (1) Mrs. Davis told me that he does not now sing much, whereas singing used to be his favourite amusement. Dr. Bucke speaks of him as singing whenever he was alone, whatever he might be doing: e.g. while taking his bath, dressing, or sauntering out of doors. (2) He talks more than he used to do. He certainly talked a good deal to me, and as freely and unconstrainedly as to an intimate and lifelong friend.