Visits to Walt Whitman in 1890–1891: Visit to West Hills

NOTES OF VISIT TO WALT WHITMAN

AND HIS FRIENDS IN

1890

med_sm.00066_large.jpg

med_sm.00066_large.jpg

VISIT TO WEST HILLS

Monday, July 21st.—After a brief visit to some relatives at Wheatley, Long Island, I took train to Huntington. Here a letter awaited me from Mr. Herbert Gilchrist. A darkey driver took me in a "Brewster's side-bar wagon" on to West Hills, where, after a little difficulty—for candour compels the admission that the name of Walt Whitman is not so familiar in the neighbourhood as I expected—I found the farm-house in which he was born. Alighting, I went up to an elderly, farmer-looking man in the yard.

"Good-day to you! Are you Mr. Henry Jarvis?" I asked.

"I believe I am," he replied.

"Is this the farm where Walt Whitman was born?" I enquired.

"Walter Whitman? I guess so," he replied.

"Well," said I, "I've come a long way to see this house, and I should much like to stay in the neighbourhood all night, if I possibly could."

After a little further talk, he "guessed I could stay

there," but in a few minutes his wife came out and said she could not

accommodate me. However, after a little persuasion, she agreed to let me stay

the night; and here I am, writing  med_sm.00200_large.jpgthis note in the very house—perhaps

the very room—in which Whitman was born, seventy-one years ago!

med_sm.00200_large.jpgthis note in the very house—perhaps

the very room—in which Whitman was born, seventy-one years ago!

After supper with the family I spent three delightful hours strolling quietly about the neighbourhood. It is richly wooded, the vegetation is luxuriant, and the roads seem to cut their way through a dense undergrowth of shrub and grass and creepers, which lines each side, climbs high up the trees, and completely covers the fences.

The evening was gloriously fine—another superb sunset, the sun going down in splendour and trailing after him clouds of crimson and vermilion, shading off into violet, pink, orange, saffron and pale lemon—and "artist's despair" sunset, which was followed by a starry night of unusual brilliance and beauty. I had witnessed just such another starry night at sea—the Milky Way stretching like a luminous belt across the star-sprinkled sky, the constellations shining in unsurpassed brilliance, and almost shaming the light of the crescent moon.

I wandered on in the waning light until the sun was below the horizon and the peaceful beauty of the scene at "the drape of the day" was most impressive, with the all-pervading music of the crickets filling the air, until the young katydids began their evensong, and the fire-flies flashed their phosphorescent lights on the grass, the roadway, the trees and the fences. I strolled along the road to where all insect sounds ceased, and there stood alone with the deep solitude and peace and the sublime spectacle of the luminous, crowded heaven above.

med_sm.00201_large.jpg

med_sm.00201_large.jpg

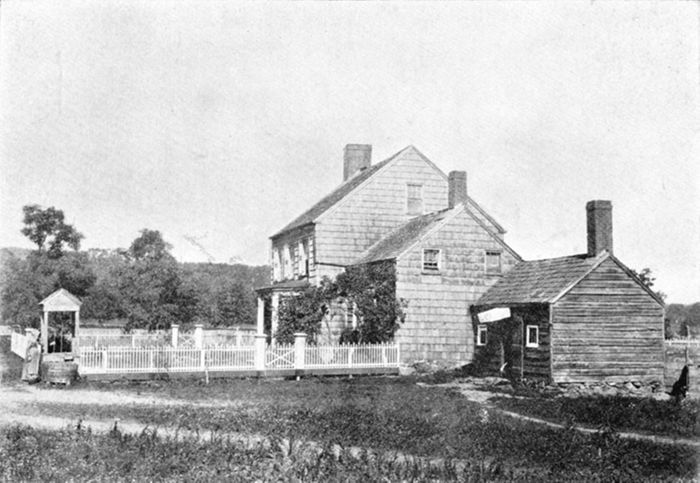

WEST HILLS—WHITMAN'S BIRTHPLACE—FROM FARMYARD (1904).

Photograph of Whitman's birthplace home in West Hills, on Long Island, New York.

WEST HILLS—WHITMAN'S BIRTHPLACE—FROM FARMYARD (1904).

Photograph of Whitman's birthplace home in West Hills, on Long Island, New York.

med_sm.00202_large.jpg

med_sm.00202_large.jpg

I do not remember to have experienced a solitude so utter or a silence so profound as when I stood there under the silvery radiance of the moon, "alone with the stars." They seemed charged with a new beauty and a new meaning addressed to my individual soul; and long did I stand there, drinking in peace, contentment and bliss.

—After a refreshing night's sleep I awoke to the singing of some sweet little songsters at my window. What they are nobody here can tell me, but they are certainly not English. Even the so-called robin is not the English robin, but seems to be a sort of cross between it and a thrush, being almost as large as the latter, with a red breast and a long spread-out tail, which it flicks about with sharp, sudden, spasmodic jerks, like a blackbird.

I was up betimes, and went out into the grateful morning air and the beautiful sunshine which flooded and steeped everything with its glory.

I walked, or rather waded, through a field of tall, rank grass, wild flowers and

weeds, rising almost breast-high, and was amazed at the wealth of colour, and the multitudinous abundance and variety of

insect life. Great club-bodied dragon flies buzzed with their gauzy, diaphanous

wings; butterflies of every conceivable tint and hue hovered around or fluttered

from flower to flower; brown locusts and green grasshoppers shuffled and fiddled

on the slender, bending stalks of the tall, golden-headed grasses;

yellow-bodied, black-barred bees hummed as  med_sm.00203_large.jpg

they flitted from the nectar-laden chalices; flies, moths and "bugs" of all

kinds were there in almost countless numbers; and the katydids were loudly

whispering their self-contradictory assertions, that "Katy did," and "Katy

didn't." Where could such a scene as this be found but in America?

med_sm.00203_large.jpg

they flitted from the nectar-laden chalices; flies, moths and "bugs" of all

kinds were there in almost countless numbers; and the katydids were loudly

whispering their self-contradictory assertions, that "Katy did," and "Katy

didn't." Where could such a scene as this be found but in America?

Soon—too soon, alas, for I was reluctant to leave this charming district, the motherly-kind Mrs. Jarvis and her interesting household—my darkey came along with his wagon, to take me to Centreport Cove, to visit Mr. Herbert Gilchrist.

On the road we met an old man named Sandford Brown, who, I had been told, had known Whitman in his youth. We stopped him, and the following are some of the scraps of his talk:—

"Walter Whitman, or 'Walt,' as we used ter call him, was my first teacher. He 'kept school' for 'bout a year around here. I was one of his scholars,

and I used ter think a powerful deal on him. I can't

say that he was exactly a failure as a teacher, but he was certainly not a

success. He warn't in his element. He was always

musin'

an'

writin', 'stead of

'tending to his proper dooties; but I guess

he was like a good many on us—not very well off, and had to do somethin' for a livin'.

But school-teachin' was not his forte. His forte was poetry.

Folks used ter consider him a bit lazy and indolent,

because, when he was workin' in the fields, he

would sometimes go off for from five minutes to an hour, and lay down on his

back on the grass in the sun, then get up and do some writin', and the folks used ter say he was

idlin'; but I guess  med_sm.00204_large.jpg he was then workin' with his brain, and thinkin'

hard, and then writin' down his thoughts.

med_sm.00204_large.jpg he was then workin' with his brain, and thinkin'

hard, and then writin' down his thoughts.

"He was a tall, straight man, but not so tall as his father and his uncle, who were about 6½ feet high."

Here I showed him the portrait in "Leaves of Grass," when he said that he did not recognize the features as he then knew them, but he did recognize the negligent style of the dress, the open collar and the "way of wearin' the hat."

"He kept school for a year," he went on, "and then his sister"—Fanny, he thought—"succeeded him. I did not see him again for about forty years, when one day he came to my house and asked me,—

"'Do you know anything about Walt Whitman?'

"'I should think I do,' I said. And I looked at him, reco'nizin' him, and said,—

"'Yes, an' I know Walt Whitman.'

"'Yes,' said Walt holding out his hand, 'I see you do; but I have seen those that didn't.'

"I'm one of the very few left," continued the old man, "that knew him in the old days, but there are enough on us to be his pall-bearers, and I hope, when his time comes, that he will elect to lie here, where all his forbears rest."

I told him I had seen a newspaper paragraph to the effect that he had selected his burial place in Camden, at which he hung his head, and said sadly,—

"Oh, I'm very sorry if that's so. I've never read his

'Leaves of Grass,' because I could not afford to buy it; but I've heard tell

that some  med_sm.00205_large.jpg folks say some parts of it

is immoral; but I can't believe that, because Walt was always a man of

strict propriety. But it may be that those folks don't quite understand his

mean'. He is a very well eddicated man, and a very deep think' man, and I am

quite sure that he would write nothing' but what he believed to be proper

and true. I believe he is far in advance of his time."

med_sm.00205_large.jpg folks say some parts of it

is immoral; but I can't believe that, because Walt was always a man of

strict propriety. But it may be that those folks don't quite understand his

mean'. He is a very well eddicated man, and a very deep think' man, and I am

quite sure that he would write nothing' but what he believed to be proper

and true. I believe he is far in advance of his time."

"Yes," I said, "he will have to be dead and buried a hundred years before he is properly appreciated."

At this the old man looked suddenly up at me, and said quite sharply—

"Bury Walt Whitman, did you say? No, sir-r! They'll never bury Walt Whitman! Walt Whitman'll never die!"—and he nodded significantly at me, as much as to say, "I have you there!"

"And so," I said, "you believe in the immortality of the soul?"

"Well, naow," he replied slowly, "it would take too long to explain my views on that subject, and I might say somethin' which might mislead you; but I may say I believe that nothin' really dies that has ever lived. I believe, too, that I once existed before I lived in my present form, and that I shall again live as an individual after I have changed my present form."

"Why," I said, "that is something like Whitman's belief."

"I don't know whose belief it is, but I tell you it's mine," he said.

"Walt Whitman is a great favourite of mine," he continued, "and I think a good deal on him.  med_sm.00206_large.jpg I don't say that because I know he

has now made a name for himself and become famous. Lots of folks want to

claim friendship with him now, but I hear he won't have 'em. But it's what I've allus thought,

and I would give almost anythin' just to take

him by the hand and look in his face—though I wouldn't tell

him—oh, dear no!—I wouldn't tell him—I couldn't tell

him—what I think on him!"

med_sm.00206_large.jpg I don't say that because I know he

has now made a name for himself and become famous. Lots of folks want to

claim friendship with him now, but I hear he won't have 'em. But it's what I've allus thought,

and I would give almost anythin' just to take

him by the hand and look in his face—though I wouldn't tell

him—oh, dear no!—I wouldn't tell him—I couldn't tell

him—what I think on him!"