Visits to Walt Whitman in 1890–1891: First Visit to Camden, September 8th and 9th

VISITS TO WALT WHITMAN AND HIS

FRIENDS, Etc., IN

1891

med_sm.00067_large.jpg

med_sm.00067_large.jpg

FIRST VISIT TO CAMDEN

SEPTEMBER 8TH AND 9TH

The British Prince arrived in Philadelphia at noon on Tuesday, September 8th,

after an unusually protracted voyage, having been delayed considerably by a

storm in mid-Atlantic. I soon distinguished Dr. Bucke amongst the crowd on the

wharf waiting the arrival of the ship, and with him were Horace Traubel and

Whitman's nurse, Warren Fritzinger ("Warry"). I recognized Warry at once from

his photograph, though the actual man looked better than the portrait, and he

won my heart immediately. Horace Traubel, too, seemed a familiar figure, and

quickly made me feel as though we were old and close friends. After clearing the

customs and arranging for my baggage to be sent to Traubel's, we walked on

together, Bucke taking my arm, till we came to a point where we had to separate,

—Traubel to go to business and Warry to return home to inform Whitman of

my arrival. Dr. Bucke and I then took a car into the town, where we had dinner

together in a large restaurant in the "Bullitt Building." Returning to the

street Bucke said: "Now we'll go see Walt."

We walked down to the ferry, crossed over to Camden, and then took a cab to  med_sm.00207_large.jpg Mickle Street—"to Mr. Whitman's."

We alighted opposite the door of the house and Bucke walked up to an open window

on the ground floor, near which Whitman usually sat when downstairs, and looked

in to see if he was there. As the room was unoccupied, he went to the front

door, opened it, walked in, and turned to the left into the front parlour, I following him. We were joined immediately by

Mrs. Davis, who shook hands with me very cordially and expressed her pleasure in

seeing me. She then went upstairs to notify Whitman of our arrival, and we sat

down to await her return. I looked round the room, illustrated and described in

Dr. Johnston's "Notes," and examined the various photographs on the

mantel-piece, amongst which I was pleased to see one of our "College" group, one

of Dr. Johnston, etc. Mrs. Davis returned presently, saying that Mr. Whitman was

awaiting us, and Dr. Bucke and I went upstairs, he preceding me and walking

straight into the front room. As I followed I heard Whitman's voice: "Come right in! Have you got Wallace with you?" Then

face to face with Whitman, and the grip, long and kind, of his outstretched

hand.

med_sm.00207_large.jpg Mickle Street—"to Mr. Whitman's."

We alighted opposite the door of the house and Bucke walked up to an open window

on the ground floor, near which Whitman usually sat when downstairs, and looked

in to see if he was there. As the room was unoccupied, he went to the front

door, opened it, walked in, and turned to the left into the front parlour, I following him. We were joined immediately by

Mrs. Davis, who shook hands with me very cordially and expressed her pleasure in

seeing me. She then went upstairs to notify Whitman of our arrival, and we sat

down to await her return. I looked round the room, illustrated and described in

Dr. Johnston's "Notes," and examined the various photographs on the

mantel-piece, amongst which I was pleased to see one of our "College" group, one

of Dr. Johnston, etc. Mrs. Davis returned presently, saying that Mr. Whitman was

awaiting us, and Dr. Bucke and I went upstairs, he preceding me and walking

straight into the front room. As I followed I heard Whitman's voice: "Come right in! Have you got Wallace with you?" Then

face to face with Whitman, and the grip, long and kind, of his outstretched

hand.

"Well," he said, with a smile, "you've come to be disillusioned, have you?"

Of course I said that I had not, but with what words I do not know.

He was sitting in a chair near the stove, and I seated myself in a chair opposite to him, with Dr. Bucke to my left.

Of course I had had a previous conception of my own of Whitman and his room,

derived from  med_sm.00208_large.jpg the descriptions and

photographs by Dr. Johnston and others; and, equally of course, this was

instantly corrected and supplemented to a considerable extent by the actual

facts. But any partial sense of strangeness resulting from this was immediately

offset by the unaffected and homely simplicity of Whitman's greeting, the first,

kind grip of his hand, his look into my eyes, and his smiling suggestion that I

should be "disillusioned."

med_sm.00208_large.jpg the descriptions and

photographs by Dr. Johnston and others; and, equally of course, this was

instantly corrected and supplemented to a considerable extent by the actual

facts. But any partial sense of strangeness resulting from this was immediately

offset by the unaffected and homely simplicity of Whitman's greeting, the first,

kind grip of his hand, his look into my eyes, and his smiling suggestion that I

should be "disillusioned."

Indeed, I was a little disillusioned. The reality was simpler, homelier and more intimately related to myself than I had imagined. I had long regarded him as not only the greatest man of his time but for many centuries past, and I was familiar with the descriptions given by others of the personal majesty which was one of his characteristics. But any vague preconceptions resulting from these ideas were instantly put to flight on coming into his presence. For here he sat before me—an infirm old man, unaffectedly simple and gentle in manner, giving me courteous and affectionate welcome on terms of perfect equality, and reminding me far more of the common humanity to be met with everywhere than suggesting any singular eminence or special distinction. Indeed it was our common humanity as it will appear when, as in Whitman, it is stripped of all that divides or disguises man from man.

I was to realize very soon after, as fully as any, the impressions of majesty, and of something in him "more than mortal," which others have experienced and referred to, but my first and predominant impressions on this first encounter were those which I have just described.

med_sm.00209_large.jpg

med_sm.00209_large.jpg

No doubt Dr. Bucke's presence contributed to this sense of intimate and homely familiarity. For Bucke had already exemplified for us the same qualities; and Walt himself was hardly more simple and unaffected in his intercourse with all classes of people than was Bucke. It was very interesting to see them together. Bucke tall and powerful in physique, robust and virile, easy and unaffected in manner, and direct almost to bluntness in speech, his voice strong and slightly harsh, and addressing Walt, for all his profound reverence for him, with the careless ease and frankness of an equal comrade. Walt, originally robust and powerful as he, now grown old and feeble, presented a striking contrast with Bucke's more exclusively masculine nature by his exquisitely delicate sensitiveness, his gentleness and refinement of speech and manner, and also by his deep and sympathetic tenderness, "maternal as well as paternal."

I can only give disjointed scraps of the conversation, for it was late that night

before I was free to write them down, and I had experienced so many new

impressions, and had seen and heard so much of intense interest to me, that my

memory could not hold all the details of the conversation. Of course even a

complete record of the spoken words would only present the least important

elements of the general effect upon me of this my first interview with Whitman.

The changing expressions of the face, the look of the eyes, the wonderfully

varied and subtle modulations of the voice, the pose and aspect of the whole

figure, and the yet deeper, more potent, and indescribable  med_sm.00210_large.jpg influence of personality—these

cannot appear in any record. I can only give such scraps of talk as I have

preserved, and add some accounts of the impressions I experienced at different

stages of our talks and afterwards.

med_sm.00210_large.jpg influence of personality—these

cannot appear in any record. I can only give such scraps of talk as I have

preserved, and add some accounts of the impressions I experienced at different

stages of our talks and afterwards.

W. W. "What sort of trip have you had? Well, you are welcome to America, and welcome to Walt Whitman. But you have come to be disillusioned!"

"I have written a letter to Dr. Johnston which I have purposely kept back till now. I will add a few lines after supper, saying that you are here, and it will be mailed to-night."

"What a splendid lot of fellows you have in Bolton!"

J. W. W. "I am afraid there is an exaggerated notion here of what we are. We are only commonplace fellows who happen to be good friends."

W. W. "Oh! we size them up pretty well, and succeed better than you do with us. We all swear by them here."

Dr. B. "Horace has had a letter from Symonds this morning and will let you have it tonight."

W. W. "Have you read it?"

Dr. B. "Horace read it to me as we were waiting for Wallace. I guess Symonds is in a bad way—dying. I don't mean that he will die in a few days, but in a few months likely. He talks of having his 'Warry' with him in Florence—someone to attend to him." (W., evidently affected, listening silently, except for an occasional "Oh!"—spoken with great tenderness.)

med_sm.00211_large.jpg

med_sm.00211_large.jpg

After a pause, Dr. B. "Of course he's been ill a long time."

W. W. "Yes. He's like a—" (I didn't catch the word)—"as we call it; but the divine Soul shines through it all.—That's his portrait, Wallace" (pointing to end of mantel-piece).

I took it down, looked at it, and passed it to Dr. B.

Dr. B. "How old is he, Walt? Sixty?"

W. W. "I should say he must be six or seven years younger than that."

Dr. B. "There can't be any immediate danger. Someone has asked him to write a life of Michael Angelo, and he had some thought of doing it. So he's likely to live some time yet."

W. W. "Yes; just hanging on, like me."

(Dr. Bucke said to me afterwards, with reference to the abrupt way in which he had told Walt that Symonds was very ill, that the best plan always was to tell him the worst right off. Then, if he found that things were not so bad, he was relieved and pleased.)

W. W.

"There's a fine group of friends at Melbourne. One of

them, Bernard O'Dowd, writes to me and gives me quite interesting off-hand

pictures of Australian life, sheep-walks, grazing, etc. They have a

bell-bird there, as they call it, a bird about so high," (indicating the

height with his hand) "with a note like the striking of a

bell, and with an undertone of something weird and plaintive. Barny has

traveled a good deal and is quite a 'Leaves of Grass' fellow. There are

about twelve persons in the group, some of them women. They meet

frequently—Sunday even-  med_sm.00212_large.jpgings,

etc.,—at O'Dowd's house. Barny sends me sketches of them."

med_sm.00212_large.jpgings,

etc.,—at O'Dowd's house. Barny sends me sketches of them."

I suggested that I might write to O'Dowd, mentioning Hutton, (one of our group who had been in Australia and whose wife in an Australian) and W. at once gave me his address, Dr. Bucke pronouncing it "a good scheme."

Dr. B. Speaking about some book belonging to Walt said he hoped it was not lost, and then laughed heartily and looked significantly at the litter of papers and books on the floor described in Dr. Johnston's "Notes."

W. W. "You may laugh at my want of order, but I have given it up. The exertion is too much for me, and when I have read a paper I just drop it on the floor."

Dr. B. "Walt, I'm going to take Wallace to Fairmount Park to-morrow."

W. W. "Yes, he should see it."

Dr. B. "And Anne" (Mrs. Traubel) "and Mrs. Bush will go with us. Will you come?"

W. W. "No, I think I must not do so. I should like to come."

Dr. B. "I will not urge it, as it involves three or four miles of rough jolting road in the town itself."

W. W. "My bladder trouble must be remembered too. I soon fill up. I am like the man whom the doctor ordered to drink a quart of a certain liquid. 'But, doctor, I only hold a pint!' My friends do not realize my condition. They persist in imagining that I am like them."

Later he said that he would go downstairs, and called for Warry to assist him.

Dr. Bucke and  med_sm.00213_large.jpg I left the room and went

down to the front parlour in which we had previously sat. Here Bucke took a seat

in the corner to the left of the doorway and near the front wall, and I seated

myself on his right. Opposite to us, in the corner to the right of the window,

stood Walt's huge arm chair, presented to him by Thomas Donaldson's family. Walt

followed us, stick in hand, and as he advanced to his chair, he called my

attention to it, saying: "Have you noticed my chair? It is

strong and timbered like a ship. I thought of sending one like it to

Tennyson."

med_sm.00213_large.jpg I left the room and went

down to the front parlour in which we had previously sat. Here Bucke took a seat

in the corner to the left of the doorway and near the front wall, and I seated

myself on his right. Opposite to us, in the corner to the right of the window,

stood Walt's huge arm chair, presented to him by Thomas Donaldson's family. Walt

followed us, stick in hand, and as he advanced to his chair, he called my

attention to it, saying: "Have you noticed my chair? It is

strong and timbered like a ship. I thought of sending one like it to

Tennyson."

Dr. B. "How would you get it to Tennyson?"

W. "I thought once of sending it by the Smiths, but I think I will ask Herbert Gilchrist to take it. He is going to England soon, and he knows the way about. He know Hallam well."

Here Mrs. Davis came in with Whitman's supper, which she placed on a light table before him, with a cup of tea, etc., of which he partook, speaking only at intervals.

W. "My supper is my main meal now. My breakfast used to be, but I have changed that, or it has changed itself."

Lifting up a volume of Scott's poems near him he held it towards me, saying:—

"Wallace, here is a book I have had for the last fifty years. It is an inexhaustible mine of interest. I used to read it and re-read it and re-read it, and now I read the interminable prefaces and notes. They are full of meat. What a talker Scott was!"

J. W. W. "Have you read Scott's Diary recently published?"

med_sm.00214_large.jpg

med_sm.00214_large.jpg

W. "No; do you think I should do?"

(Later) "Wallace, if any of your friends like good eating, Mrs. Davis cooks a dish of tapioca and stewed apples together, which is very good, and which I am having now."

He invited me to a cup of tea, but I declined, as we had promised to go to supper at Traubel's.

A photograph of Mrs. Davis and the dog, "Watch," hung upon the wall near me, to which he directed my attention.

Speaking of my trip he said that he had felt uneasy in consequence of my late arrival. He found that as he got old he was given to imagine things, as old people do, and hearing of the storm in the Atlantic, and the ship being thirteen days out, he grew uneasy.

(Warry told me afterwards that Whitman had sent him down to the wharf for three or four mornings in succession to make enquiries about the ship, and that when he returned each time with the report that no information had been received, Whitman had once exclaimed:—"the damned ship!")

Horace Traubel came in presently with the easy unobtrusive familiarity of an

intimate of the household, and, after greeting us all quietly, seated himself

near the fireplace, the four of us forming an irregular square. He was soon

asked by Walt if he had Symonds's letter with him. Traubel at once handed it to

him, and suggested that he should read it aloud for me; but it was ultimately

settled that he should read it later at his leisure, and return it the following

afternoon. It was very  med_sm.00215_large.jpg beautiful to see

the way he took the letter and the tender care with which he put it in his

inside breast-pocket.

med_sm.00215_large.jpg beautiful to see

the way he took the letter and the tender care with which he put it in his

inside breast-pocket.

A rather prolonged conversation then took place between Bucke and Traubel about

Canadian affairs and politics, during which Walt sat silent, looking sideways

through the window to his right. He appeared to by physically tired and weary,

and was probably in some pain or discomfort as well; and, though he listened

with interest and courtesy to all that was said, and was obviously one with us

in fullest comradeship and sympathy, his thoughts evidently travelled over a

wider area than that of the immediate talk and scene. I sat in close watch of

his every look and movement, and I shall never forget the noble and pensive

majesty of his appearance and expression; far beyond that of any portrait or

picture I have seen of him, or of any other picture or sculpture. His great head

seen almost in profile, with its lofty and rounded dome, his long white hair and

beard, the striking and impressive effect of what seemed from my position the

immense arch of his high-set and shaggy eyebrows, his brow seamed with wrinkles,

his whole aspect suggested something primeval, preterhuman, and of deeply moving

power. His expression was pensive and almost mournful, as that of one who has

had long and intimate experience of all human sorrows ("a man of sorrows and

acquainted with grief,") and full of a profound and wistful tenderness and

compassion; but it was also that of one who is visibly clothed with immortality,

sharing to the full the limitations of our mortal life and yet ranging in worlds

beyond our ken. And though

med_sm.00216_large.jpg

med_sm.00216_large.jpg

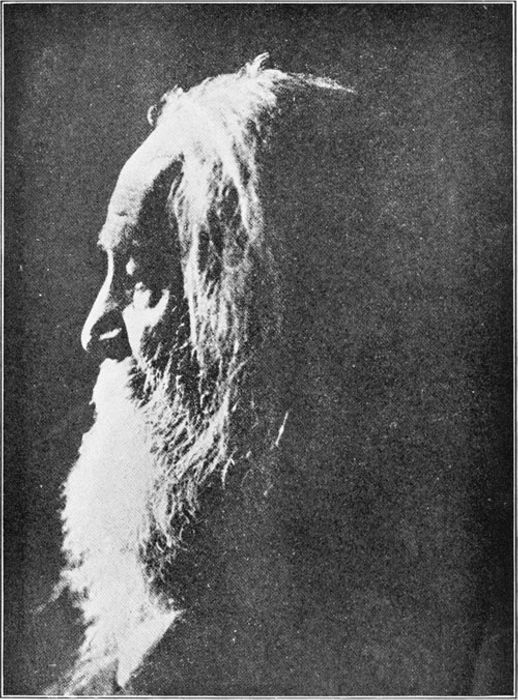

SCULPTOR'S PROFILE OF WALT WHITMAN, MAY 1891.

Photograph #129, showing Whitman's face in profile, taken by Samuel Murray in May 1891.

SCULPTOR'S PROFILE OF WALT WHITMAN, MAY 1891.

Photograph #129, showing Whitman's face in profile, taken by Samuel Murray in May 1891.

med_sm.00217_large.jpg

in present pain and weakness he was

uncomplaining, patient, gentle and loving.

med_sm.00217_large.jpg

in present pain and weakness he was

uncomplaining, patient, gentle and loving.

As I sat watching him, after a time a strange and unique experience happened to me. I am not psychic or clairvoyant and I have never engaged in any experimental investigation of spiritualism or the "occult." But quite suddenly there came into my mind what I can only describe as a most vivid consciousness of the presence with us of my mother, who had died six and a half years before. I seemed to see her mentally with perfect clearness, her face radiant with the joy of our realized communion and with more than its old expression of sweetness and love, and to feel myself enwrapped in and penetrated by her living and palpitating presence. I record it here because it seemed equally indubitable that Walt was somehow the link between us, and as if his presence had made the experience possible.

I had not been thinking about my mother, and at the time I was too much engrossed

in close observation of Walt to think of anything else. And no explanations that

have occurred to me have ever affected my inner and abiding conviction of the

essential veracity of the experience. Whether it was the result of some shifting

of my "threshold of consciousness," due to the emotional effect upon me of

Walt's appearance and expression, or due to some deeper and more direct

influence emanating from him, I do not know. I never spoke of it to him, and I

believe that Dr. Bucke was the only person in America whom I told about it, when

we were at his home in Canada, about two weeks later. But it has always seemed

to me  med_sm.00218_large.jpg to be significant in relation to

many passages in "Leaves of Grass."

med_sm.00218_large.jpg to be significant in relation to

many passages in "Leaves of Grass."

During the desultory conversation which followed I once said something in praise of Warry—I forget in what connection. "Yes," responded Walt, "he is faithful, true, and loyal—or leal. What is the meaning of leal?"

Finally he called for Warry and said:— "Well, friends, I must bid you good-night, as I must go upstairs." He took his stick and stood up, leaning upon it, and as he passed he extended two fingers from the handle of his stick to me and advised me to sit in his chair and see how comfortable it was. I stood beside him as his tall figure passed slowly out of the room; and couldn't help noticing the extraordinary delicacy and beauty of form of his ears, so often noted by others. Soon after we left and proceeded to Traubel's.

Throughout the following day, while the impressions of my first visit to Whitman

were yet strongly and deeply felt, a line in O'Connor's famous letter of 1865,

in which he described Whitman as "the

grandest gentleman that treads this continent," recurred continually to

my mind as an apt summary of the various impressions he had made upon me. I

still think it apt. It marks first of all the grandeur of personality, in its

range of character and power, which is obvious to any competent student of his

work and life, and which one soon felt in his presence. And it rightly lays

emphasis on qualities in him which have often been depreciated, but which in all

I saw of him were equally supreme and unique. I am only concerned  med_sm.00219_large.jpg here with my own experience, without

reference to anything else, and I am anxious to avoid both exaggeration and

understatement, and I can only say that in his full and rounded combination of

all the qualities which go to the make-up of a true and perfect gentleman

(including all those enumerated by Ruskin in his analysis of gentleness as

contrasted with vulgarity) he was not only unequalled but unapproached by any

one else whom I have ever met.

med_sm.00219_large.jpg here with my own experience, without

reference to anything else, and I am anxious to avoid both exaggeration and

understatement, and I can only say that in his full and rounded combination of

all the qualities which go to the make-up of a true and perfect gentleman

(including all those enumerated by Ruskin in his analysis of gentleness as

contrasted with vulgarity) he was not only unequalled but unapproached by any

one else whom I have ever met.

After leaving Mickle Street a walk of about ten minutes took us to Traubel's home in York Street. Here I received a hospitable welcome which made the evening very memorable to me, both in itself and because of the high qualities of our host and hostess.

Traubel was at that time thirty-two years of age, clerk in a bank in

Philadelphia, actively associated with the Ethical Society there and elsewhere,

and editor of the Conservator, then it its second year,

much of which he wrote himself. He was of medium height and rather long in body,

with a well-developed head of great length from front to back ("always the best

sign of intellect," says Carlyle), wavy hair, and square forehead. He had fine

clear eyes, grayish-blue in colour, nose somewhat

Jewish in profile, a moustache, and a delicately moulded and dimpled chin. Quiet and unaffected in speech and manner;

undemonstrative, though kind and brotherly and always silently planning for my

benefit; simple, spontaneous, and natural; easily taking his part in ordinary

social talk and pleasantry, and enjoying a joke; very  med_sm.00220_large.jpg intuitive and of unusually alert and

swift intelligence, with eyes which at times showed rare penetration; a born

idealist and poet, yet a tireless worker, and with many-sided practical

ability;—he devoted himself unsparingly, during all the leisure he could

command, to the service of Whitman,—to whom he was more than a

son,—and of all his friends, as well as to the causes which he

represented.

med_sm.00220_large.jpg intuitive and of unusually alert and

swift intelligence, with eyes which at times showed rare penetration; a born

idealist and poet, yet a tireless worker, and with many-sided practical

ability;—he devoted himself unsparingly, during all the leisure he could

command, to the service of Whitman,—to whom he was more than a

son,—and of all his friends, as well as to the causes which he

represented.

His wife (to whom he had been married the previous May) was equally notable in her transparent goodness, naturalness, purity, sweetness and loyal affectionateness, as well as in her grace and charm of person and manner. With both, Bucke, who had been staying there, seemed perfectly at home, like an elder member of the family. There was also present a lady friend from New York, Mrs. Bush, who left us during the evening to visit other friends in Philadelphia. In addition to these two Mrs. O'Connor—the widow of Whitman's brilliant friends William O'Connor—had also been spending a few days at Traubel's, and had left only the previous day, after kindly protracting her stay as long as possible in the expectation of meeting me.

Traubel took me up to his study after supper and showed me his unique collection

of Whitman MSS. and other treasures. During the evening we discussed

arrangements with Dr. Bucke. It had previously been agreed that I should

accompany him to Canada, and, as he naturally desired to go home now without any

unnecessary delay after his long absence, we decided to leave Philadelphia the

following evening—I return to Traubel's four

med_sm.00221_large.jpg

med_sm.00221_large.jpg

HORACE TRAUBEL (1893).

Photograph of Horace Traubel.

HORACE TRAUBEL (1893).

Photograph of Horace Traubel.

med_sm.00222_large.jpg

or

five weeks later, and to make my home there during the rest of my stay in

America. For the morrow it had been arranged that Bucke and I should drive

through Fairmount Park—Mrs. Traubel and Mrs. Bush accompanying

us—and pay a brief visit to Whitman after our return.

med_sm.00222_large.jpg

or

five weeks later, and to make my home there during the rest of my stay in

America. For the morrow it had been arranged that Bucke and I should drive

through Fairmount Park—Mrs. Traubel and Mrs. Bush accompanying

us—and pay a brief visit to Whitman after our return.

—Traubel left us after breakfast to go to business, and at nine o'clock Warry came round, as arranged, with a two-horse buggy which he had engaged for us. Before returning he told me that Whitman was about the same as on the previous day and had passed a fair night. He had sent a letter to Dr. Johnston by the previous evening's mail, and Warry had also written. Dr. Bucke drove off in the buggy to call for Mrs. Bush, and Mrs. Traubel and I followed later to join them at an appointed rendezvous in Philadelphia.

It was a day of perfect loveliness and the long drive through the park and along

the Schuykill river and back—with lunch in Germantown—was most

enjoyable. We arrived at Traubel's again about five o'clock and, after leaving

the ladies there, Bucke and I drove to Whitman's where we stayed about half an

hour. Dr. Bucke went upstairs at once to see Whitman, while I conversed for a

few minutes with Mrs. Davis and Warry, to whom I gave little presents from

Johnston and myself. I then followed Bucke upstairs, and on knocking at the door

of Whitman's room heard both call to me to come in. As I entered Whitman haled

out his arm at fell length, and grasping my hand in his own held it steadily for

some time, saying with a smile: "I won't say as I  med_sm.00223_large.jpg said yesterday that you come to be

disillusioned." Horace Traubel was also in the room and nodded

pleasantly to me. A little talk followed between the three, of which I have no

record, Whitman always addressing Bucke as "Maurice."

med_sm.00223_large.jpg said yesterday that you come to be

disillusioned." Horace Traubel was also in the room and nodded

pleasantly to me. A little talk followed between the three, of which I have no

record, Whitman always addressing Bucke as "Maurice."

I had with me present of some underwear sent to Whitman by one of our group—Sam Hodgkinson—who was a hosiery manufacturer. I told him about it and, at his request, opened the parcel to show it to him. He took the goods in his hands and admired them—Bucke assuring him that nothing could be better for winter wear. He showed me the sleeve of the vest he was then wearing; knitted fine and suitable for the season. I told him that Johnston and I had intended the present to come from ourselves, but as Hodgkinson had insisted, we were left at the last moment without anything. "Well," he said, "but you've brought yourself!"

I then showed him several photographs by Dr. Johnston, which he examined with the

utmost courtesy and interest. He was chiefly interested in some pictures of the

British Prince (taken by Johnston the previous year) and of the steerage

passengers—mostly foreign immigrants including several

Armenians—saying: "The human critter is pretty much

the same everywhere!" But the photograph which interested him most of

all was that of a stowaway—a man with a sooty face, clear wide-open eyes,

and a hunted, wistful expression which was very pathetic. Whitman looked at it

closely and absorbingly for a long time. I wish it were possible to convey in

print the deep and tender compassion, or the wonderfully sympathetic  med_sm.00224_large.jpg and subtle modulations of voice, with

which he said: "Poor fellow!—I suppose they would

have to take him on? Poo-or fel-low!"

med_sm.00224_large.jpg and subtle modulations of voice, with

which he said: "Poor fellow!—I suppose they would

have to take him on? Poo-or fel-low!"

He grew physically tired, however, of looking at them, so I picked out those chiefly meant for him, or most likely to interest him, and put them together on his table. Our time, too, was limited, and we rose to go. As we did so Dr. Bucke said: "Well, Walt, I must go. I shall see you again before long. You are better now than you have been for three years back."

W. W. "But I so soon give out."

Dr. B. "You do. I know you do."

W. W. "But I recuperate. I suppose it is quite appropriate that I should hold out so."

"Good-bye, Wallace. I hope you will have a pleasant journey. I traveled along the same route, I think, and I got along very well."

Before leaving the house we spent a few minutes downstairs with Mrs. Davis and Warry. Mrs. Davis invited me very cordially to come in as often as I chose after my return to Camden, to make myself quite at home, ask any questions I wished, and when Whitman was too unwell to see me to sit with them.

We drove to Traubel's to supper, after which we had a little chat, and Mrs. Bush gave us some very excellent music on the piano. One item of the talk (in connection with the packing of our belongings) was a little story of Whitman's. "Moses, have you got all my things together?" "Yes, massa, I'se got all, at least!"

Dr. Bucke left at seven o'clock to make a call, and I left half an hour later,

Traubel accompany-  med_sm.00225_large.jpging me to the Depot in

Philadelphia. The new moon was shining, and the lights on the river as we

crossed it were very beautiful. Traubel's quiet talk, as we walked together,

impressed me as these did, and brought him very near to my heart and soul.

med_sm.00225_large.jpging me to the Depot in

Philadelphia. The new moon was shining, and the lights on the river as we

crossed it were very beautiful. Traubel's quiet talk, as we walked together,

impressed me as these did, and brought him very near to my heart and soul.