Saturday, August 4, 1888.

Saturday, August 4, 1888.

In the progress of W.'s disease this has been one of his worst days. Till three o'clock—all through the morning and the hours of the early afternoon—he "felt utterly exhausted—sick in head and body—with everything promising another spell except the spell itself." To-night complains of being "melted and weak though better." The day very hot. Has done practically nothing except write to Bucke. Read no proofs. "On the whole I feel like Abe Lincoln who would not growl over the scars and the losses but thought that the government was lucky to come out of its troubles alive." Went on: "I have been incessantly thinking of the fearful, frightful tragedy in New York—that terrible fire in the tenements last night. I often wonder how the people in those foul rookeries manage to exist anyhow in such weather. I have often been accused of turning a deaf ear to that side of life—of being too unconcerned—of treating it as if it was not. Lately, as I have sat here thinking, it has come upon me that there must be some truth in the charge—that I should have studied that strata of life more directly—seen what it signifies, what it starts from, what it means as a part of the social fabric. I have seen a lot of the rich-poor—of the people who have plenty yet have little—of the miseries of the well-to-do, who are supposed to be exempt from creature troubles. One of the painful facts in connection with this human misery—a fact insisted upon by the men who know most and who know what to do with their knowledge—is that the evil cannot be remedied by any one change, one reform, or even half a dozen changes and reforms, but must be accomplished by countless forces working towards the one effect. Hygiene will help—oh! help much. But how will we get our hygiene? I am quite well aware that there are economic considerations, also, to be taken into account. It strikes me again, as it always has struck me, that the whole business finally comes back to the good body—not back to wealth, to poverty, but to the strong body—the sane, sufficient body." I said: "You don't expect the sane body in the tenements, do you?" "No—I do not. The tenements are hot-beds of disease—scrofula, syphilis, of everything, almost: disease just fattens in the tenements. You have touched the nerve of the trouble." "Then isn't it possible to produce social conditions which will make the sane body possible?" "Surely—surely: that is the problem. I think all the scientists would agree with me, as I agree with the scientists, that a beautiful, competent, sufficing, body is the prime force making towards the virtues in civilization, life, history, I think I now see better what you mean when you speak of the economic problems as coming before all the rest and though I have not stated it in that extreme way myself I do not doubt your position: I have great faith in science—real science: the science that is the science of the soul as well as the science of the body (you know many men of half sciences seem to forget the soul)."

O'Connor writes W. of Charles Eldridge's 1889 calendar quoted from Leaves of Grass. W. says: "It is a dubious experiment—I don't shine in bits (there are no 'gems' in Leaves of Grass) though O'Connor says this collection is a strong one. I was at first inclined to demur powerfully but suppose such an experiment may best be left to find its own level." He talked of the propositions to take him away: "I look now for a hot siege of it—for sultry weather: but after going this far we must not admit that such a little thing can keep us from going to the end. As to leaving this place just now—it is impossible—out of the question: my legs would not take me if I wished to go, as I do not. Besides, the compensation would not fit the case: while gaining something in the mountains or at the sea shore, I would lose more than I gain—lose the sense of being on a spot of my own earth, of doing what I choose—and what a comfort that is! If I went off somewhere into more complaisant surroundings—had servants at my beck, the best of food, a down bed to sleep on—what would it all come to? I might be tempted some——I could not be tempted enough to go—my decision would be finally reverse."

W. said regarding a certain passage in Leaves of Grass which I thought particularly effective: "I am glad to hear you say that. It has often happened, often happens—not with me alone—that an author thinks himself very simple, clear, true, at a point considered by others of all points silly, befogged, inane." Referring to another paper in the American series on W. W. "Well, let them go on. It is interesting to be in court and find that none of the witnesses called know anything about the case." I remarked: "You had a lot of good and right things to say about the Burroughs letter yesterday but you said nothing about Dowden's. Had you no amen for Dowden's letter?" He replied: "I am guilty—put me down for guilty. The fact is, Dowden's letter is of the best sort. I happened to say extra much of Burroughs because of what he wrote about style, which seemed to me the best first and the best last thing to be said on the subject. Dowden has a wonderful passage in his letter—a passage about death. Read it to me again, won't you? just that one bit. The whole letter is human—it is not the letter of one literary man to another but of one simple man to a man as simple as himself. Won't you read the letter?" I answered "yes". "I like to get all my relations with people personal, human. I hate to think I can possibly excite any professional feeling in another." I read the whole letter again to myself and the particular part he asked for aloud to W.

Winstead, Temple Road, Rathmines, Dublin, Oct. 4, 1876. My dear Mr. Whitman.Some days ago came my parcel—many thanks—Mr. Grosairt's books included. That for Mr. Graves had come previously. I have waited a few days expecting to hear from my brother (from Edinburgh) of the arrival of his copies, but it is sometimes his way to put off writing to me too long, and I have little doubt he has got the books safely.

Rossetti let me know from time to time any news of you that reached him, and I have to thank you for some newspapers now and again.

It was a real sorrow to us, dear friend, to hear of the death of your little nephew and namesake. A friend of mine, Harold Littledale, watched this summer by the side of a little sister (about twenty years younger than himself) who died and he told me that in the presence of death and with its consciousness enveloping him it was words of yours which expressed the deepest truths of the hour and the event. Littledale is President this year of our principal society of students in Trinity College, the Philosophical Society, and I believe his opening address, which is the event of the session, is to be partly concerned with your poetry. It was a great satisfaction to me this year, also, to get a kind of confession or self-revelation from one of the most promising men in my class of the really saving and delivering power of your writings when he was lapsing in that lethargy and cynicism which is one of the diseases of youth in our Old World, if not in your New one—(but in both I should suppose).

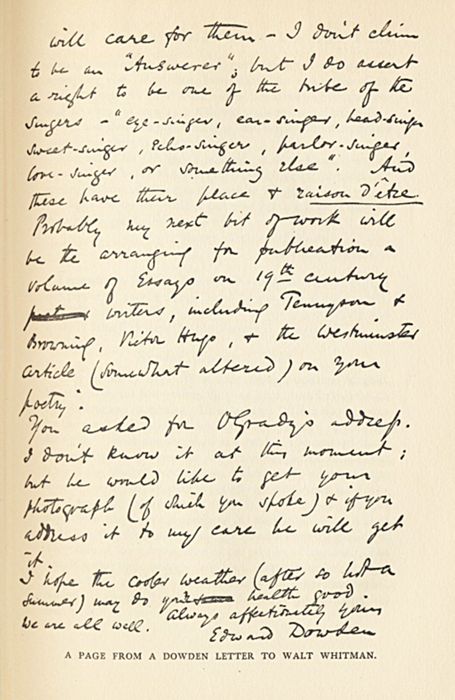

I have done too little this last summer. I copied out about 200 pp. of verse, and am about to have them published. I will send you a copy, but I doubt whether you will care for them—I don't claim to be an "Answerer," but I do assert a right to be one of the tribe of the singers—"Eye-singer, ear-singer, head-

A PAGE FROM A DOWDEN LETTER TO WALT WHITMAN.

singer, sweet-singer, echo-singer, parlor-singer, love-singer," or something else. And these have their place and raison d'etre. Probably my next bit of work will be the arranging for publication a volume of essays on 19th century writers, including Tennyson and Browning, Victor Hugo, and the Westminister article (somewhat altered) on your poetry.

A PAGE FROM A DOWDEN LETTER TO WALT WHITMAN.

singer, sweet-singer, echo-singer, parlor-singer, love-singer," or something else. And these have their place and raison d'etre. Probably my next bit of work will be the arranging for publication a volume of essays on 19th century writers, including Tennyson and Browning, Victor Hugo, and the Westminister article (somewhat altered) on your poetry.

You asked for O'Grady's address. I don't know it at this moment; but he would like to get your photograph (of which you spoke)—if you address it to my care he will get it.

I hope the cooler weather (after so hot a summer) may do your health good. We are all well.

Always affectionately yours, Edward Dowden.I repeated to W. that phrase—"the really saving and delivering power of your writings," and he repeated it back again, and still again, finally saying of it: "It has gospel beauty and beat: I hope I deserve it—oh! deserve it, deserve it."