Friday, August 17, 1888.

Friday, August 17, 1888.

W. sat in his room reading Scott's The Antiquary. 7.45 evening. He laid his book down. "Ah, Horace, is that you? And what have you done, learned, today?" For his own part he had read, written letters and received two reporters—one from the Camden Courier and one from the Philadelphia Press. Gave me a copy of As a Strong Bird, inscribed: "John Clifford, Aug: 21st '88 from Walt Whitman and Horace Traubel." "There is your little book," he said—"is that what you wanted?" "Aunt Mary," an old woman who often comes in to help Mrs. Davis, had a stroke of paralysis in W.'s kitchen this evening. W. concerned but not worried. A carriage drove up to the door. "That's for the old lady," he said: "Go down and see if you can help: I wish I could do so myself." Later on he exclaimed again: "Oh! how I should like to go down to Aunt Mary's home to see how she fares!"

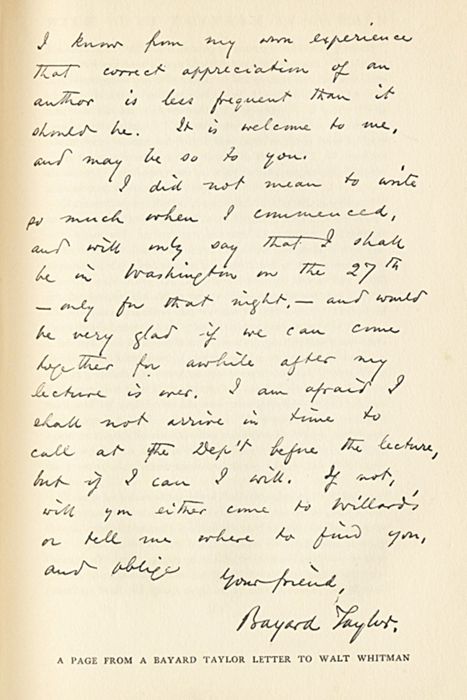

He seemed suddenly to have thought of something in danger of being forgotten. Reached forward to the table—picked up a letter. "Hurrah!" he cried, shaking it in the air. I repeated: "Hurrah!" and then asked: "But what is it?" He laughed gaily. "It's the Taylor letter, damn it—didn't you guess?" and before I could have replied he added: "It was here on the table all the time, of course, under a lot of other things. Now we have it let's keep it." He passed it across to me. "It's a warm letter," he added—"about as warm as the weather. Read it for yourself, read it for yourself! Seeing is believing: just look at it." I quoted my dentist who got off an old saw while he was working on one of my sensitive teeth: "Seeing is believing but feeling is the naked truth." W. laughed again: "That would not be regarded as quite proper but it's true, nevertheless. Read the letter to me: you will feel its naked truth before you get through." I asked W.: "Why is it you have lately had me read so many things to you that you were already perfectly familiar with?" "I don't know—read, read, and ask no questions." So I read. Kennett Square, Penna., Dec. 2, 1866. My dear Whitman: I find your book and cordial letter, on returning home from a lecturing tour in New York, and heartily thank you for both. I have had the first edition of your Leaves of Grass among my books, since its first appearance, and have read it many times. I may say, frankly, that there are two things in it which I find nowhere else in literature, though I find them in my own nature. I mean the awe and wonder and reverence and beauty of Life, as expressed in the human body, with the physical attraction and delight of mere contact which it inspires, and that tender and noble love of man for man which once certainly existed, but now almost seems to have gone out of the experience of the race. I think there is nothing in your volume which I do not fully comprehend in the sense in which you wrote; I always try to judge an author from his own standpoint rather than mine, but in this case the two nearly coincide. We should differ rather in regard to form than substance, I suspect. There is not one word of your large and beautiful sympathy for men, which I cannot take into my own heart, nor one of those subtle and wonderful physical affinities you describe which I cannot comprehend. I say these things, not in the way of praise, but because I know from my own experience that correct appreciation of an author is less frequent than it should be. It is welcome to me, and may be so to you. I did not mean to write so much when I commenced, and will only say that I shall be in Washington on the 27th—only for that night—and would be very glad if we can come together for awhile after my lecture is over. I am afraid I shall not arrive in time to call at the Dep't before the lecture, but if I can I will. If not, will you either come to Willard's or tell me where to find you, and oblige Your friend, Bayard Taylor.

W. said: "Taylor has been of recent years quoted against me—especially against the sex poems. Now, it is precisely on that point that the declarations of his letter are the most unqualified and decisive. What are we to believe? It would be easy to quote one Taylor against the other—but which against and which for?" He smiled good-naturedly: "I prefer to believe in the Taylor of my letters even if it does smack of egotism for me to do so." "Are you afraid of being accused of egotism?" "Hardly afraid—I am accused. I say just this: I hear all sorts of vague stories about Taylor nowadays—vague stories which may be false or true. Now, here are two letters: they are in his hand, he signed them, they are not vague. Why shouldn't I believe the letters?"

He said reflectively after awhile: "I wouldn't know what to do, how to comport myself, if I lived long enough to become accepted, to get in demand, to ride the crest of the wave. I would have to go scratching, questioning, hitching about, to see if this was the real critter, the old Walt Whitman—to see if Walt Whitman had not suffered a destructive transformation—become apostate, formal, reconciled to the conventions, subdued from the old independence. I have adjusted myself to the negative condition—have adjusted myself for opposition, denunciation, suspicion: the revolution, therefore, would have to be very violent indeed to whip me round to the other situation." He stopped to laugh. "But I guess there is no immediate danger: I am not very near such a crisis. I remember when Swinburne at last turned against me, John Burroughs said he felt that things were coming right again—that things had got back to their equilibrium—that the inexplicable community of admiration between him and Swinburne had come to its legitimate end—had had to perish of its own dead weight. John seemed to think that for the two of them to say the same things about me would prove either that Burroughs was not Burroughs or Walt Whitman wasn't Walt Whitman. Then came the Swinburne outburst: presto! the air was cleared: John breathed free again! It is a good story to know and tell.

A PAGE FROM A BAYARD TAYLOR LETTER TO WALT WHITMAN

I don't feel myself like damning Swinburne for saving himself!" W.'s little sallies of humor like this are always quiet. His laugh is a silent one—yet infectious. "Swinburne has his own bigness: he is not to be drummed out of all camps because he does not find himself comfortable in our camp." I said: "The people who instance Tennyson and Swinburne as masters of poetic form should not forget that both of them have in later years taken all sorts of liberties with the code." W. nodded an assent: "It is indeed so: so with Swinburne, so with Tennyson: almost phenomenally so."

A PAGE FROM A BAYARD TAYLOR LETTER TO WALT WHITMAN

I don't feel myself like damning Swinburne for saving himself!" W.'s little sallies of humor like this are always quiet. His laugh is a silent one—yet infectious. "Swinburne has his own bigness: he is not to be drummed out of all camps because he does not find himself comfortable in our camp." I said: "The people who instance Tennyson and Swinburne as masters of poetic form should not forget that both of them have in later years taken all sorts of liberties with the code." W. nodded an assent: "It is indeed so: so with Swinburne, so with Tennyson: almost phenomenally so."

Commenting on Bucke's approval of the Hicks piece: "I have not yet adjusted myself to it: I cannot tell today or tomorrow what will be my own matured impression. Judgment never comes to me in a hurry. My first notion is one of disappointment. That comes because I am at the moment too sensitive concerning the thing I did not do. Some day I will get the matter in another perspective—maybe see that it after all possesses qualities that excuse its creation." Talked of Browning's letter: "I am glad he did not come over in person: if he had done so I might have been tempted to see him—then there would have been a storm—and a storm would earn no sort of profitable interest on my present capital." Some one had been in to take W.'s picture. W. said: "So you think every man will by and by be his own photographer, painter, shoemaker, again? Well—who knows? The world is turning around again towards the simple—the condition in which each man may supply his own needs. A day may yet arrive to find us grown aboriginal again—civilized aboriginal if I may say so."

W. says he misses Kennedy's "old-time letters." "He used to write martial letters—warlike letters: was up in arms about things. He got about a good deal, saw people, had a story to tell. Now he seems too busy. When Kennedy was passing through the early stages of his faith in the Leaves—the first fervors of conversion—he made Whitman the password: opposed to Walt Whitman opposed to me—that sort of chip-on- the-shoulder business: so that in ways Sloane got unpopular—people avoided him—they didn't want to hear his wild Indian ideas, and so forth." I brought W. over today plate proofs, three sets, to page 125. Has finally decided to make the price of the book one dollar. Has finally decided "no" as to de luxe copies. "I want no autocrat editions." Heat intense all day and evening. "I manage to stay—to hold on—that's about all."

I met Edward Coates today—husband of Florence Earle. He asked me about W.'s autograph editions and the Cox portraits. "The curio collector is from everlasting to everlasting," said W., "but he has his parts, too. Some of my old editions, which I could not give away at the time, now bring fabulous prices, ridiculous prices: it beats the devil, the ups and downs of authorship—especially the downs: I've had my fill and fill again of the downs. Yes, tell the Coates people—Mrs., Mr. Coates—to come over: I will see them." Then said as to the Cox portraits: "Advise Coates to go to see William Carey—no doubt Coates is often in New York (those men are): send him, then, to my friend Carey: Carey puts up with the Century Company—works there. Carey has the photographs, all duly autographed. If Coates goes let him know that I like one of the pictures in particular—the laughing philosopher, I call it—and one other, perhaps as well—my head resting in my hands forward, this way"—indicating—"and always, of course, the unsilvered copies—always those. And should you want one of the heads, Horace, I want to give it to you." I objected: "It would be robbery." "No—no: I want to and you must let me do it." Again: "Pictures are partial—they give a dash of a man, a phase: many are called but few are chosen: there is a success here and there to a hundred failures. I guess they all hint at the man—even Herbert's, maybe, strange as that may seem. The very worst place in the world to put Herbert's picture would be right next to Eakins'. It would be sure death." W. gave me a Washington relic which he had endorsed as "Pass Burnside's Army Jan. '63." It read this way:

Headquarters Rg D. Near Falmouth Dec 27 1862.Pass the bearer Walter Whitman, a citizen, to Washington Rail R. and government steamer.

By command ofMaj Gen Sumner I N Taylor

Chief of Staff Actg—

W. said nothing much about it: "Would you like that for a curio? It won't pass for money—". I laughed and said "pass?" and he said "pass?" after me, adding: "Did you ever know me to pun? It's not in my line at all. I am guilty of most the real bad sins but that bad sin I never acquired."