Sunday, September, 9th, 1888.

Sunday, September, 9th, 1888.

Not one of W.'s best days. Very close, rainy, debilitating. I went down at seven. He lay on the bed, but knew me, dark as it was. "I know your step no matter how lightly you tread." Stayed on the bed for full half an hour. Talked very readily and easily. He wanted to get up at once but I objected. He did finally do so and go to his chair. He closed the blinds of the shutter. Adjusted the arm of the gaspipe and turned the key. Could not find a match. Fumbled about, upset the clothes-basket in which he throws his waste papers. He never said a word. Black enough to blind an owl. I then broke in and got the gas lighted. W. said: "I can generally pilot myself about here, but the devil gets into things (or me) now and then."

W. rarely reads his poems to anybody. To-night read An Evening Lull to me. His voice was strong and sweet. He never recites a poem (his own). I never had him do it for me. Occasionally he will cite a line or two. "I don't know my poems that way: any one of you fellows probably could repeat more lines from the Leaves than I could." Again: "I never commit poems to memory—they would be in my way." He further remarked: "I don't revise my revisions too much—polish: I don't hold it to be principally important to develope special technical flavors. Studying for recitation is mainly technical—tends to reaction: encourages formalism. I keep as far away from the mere machinery of composition as I can."

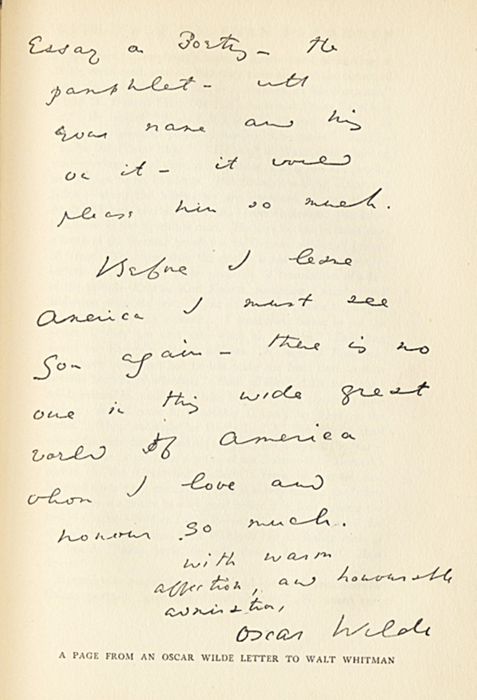

W. gave me the Wilde letter. I thought he might say more about it. He said little: only this: "It seems all straight and honest to me. I have been told a thousand times what Wilde is but I do not see why Wilde is not what he is and I am not what I am with both of us friends according each other a mutual respect. There is no parade in this note: it wears the simplest clothes—has no sunflower in its button hole—has in fact a cast of virgin simplicity, sincerity. Read it for yourself: see if the letter does not bear me out." He said nothing while I read. He had endorsed the envelope in blue pencil: "from Oscar Wilde early in '82." The postmark was Chicago, March 1. The letter was written in New York.

1267 Broadway, New York. My Dear Dear Walt—Swinburne has just written to me to say as follows.

"I am sincerely interested and gratified by your account of Walt Whitman and the assurance of his kindly and friendly feeling towards me: and I thank you, no less sincerely, for your kindness in sending me word of it. As sincerely can I say, what I shall be freshly obliged to you if you will assure him of in my name, that I have by no manner of means relaxed my admiration of his noblest works—such parts, above all, of his writings, as treat of the noblest subjects, material and spiritual, with which poetry can deal—I have always thought it, and I believe it will be hereafter generally thought his highest and surely most enviable distinction that he never speaks so well as when he speaks of great matters—Liberty, for instance, and Death.

"This of course does not imply that I do, or rather it implies that I do not agree with all his theories, or admire all his work in anything like equal measure—a form of admiration which I should by no means desire for myself and am as little prepared to bestow on another—considering it a form of scarcely indirect insult."

There! You see how you remain in our hearts—and how simply and grandly Swinburne speaks of you, knowing you to be simple and grand yourself.

Will you in return send me for Swinburne a copy of your Essay on Poetry—the pamphlet—with your name and his on it—it would please him so much. Before I leave America I must see you again—there is no one in this wide great world of America whom I love and honor so much.

With warm affection, and honorable admiration, Oscar Wilde.When I looked up after reading the letter W. asked: "Am I not right? Does he strike a false note? It all rings sound and true

A PAGE FROM AN OSCAR WILDE LETTER TO WALT WHITMAN

to me there. Everybody's been so in the habit of looking at Wilde cross-eyed, sort of, that they have charged the defect of their vision up against Wilde as a weakness in his character." I told W. Harned liked Old Age's Lambent peaks "a whole lot." He replied "So do I, if I may be allowed to say it: to me it is an essential poem—it needed to be made." Said he "had a letter from Rhys."

"He is off in Wales somewhere or was—having a good time, flitting about, seeing his own people, new things, fresh incidents. But he says nothing about our fellows—about the fellows we are interested in over there." Again: "I have another letter, too—from Rolleston: you know him?—he is the Epictetus man. He says he has in hand now a batch of the German proofs for the German edition of Leaves of Grass. You remember, the edition is not to be complete, to include all: is simply to be made up of translations of a few of the poems—Knortz, Karl Knortz, rendering a number and Rolleston doing the rest. What will the book come to, do you think? It excites my curiosity. I want your father to see the proofs if they are sent me—want his opinion." Rolleston asked for Knortz's present address. W. says of Rolleston: "We have never met but he has made me from time to time notable tenders of affection." Said of Rhys: "He has many solid, estimable qualities: lacks brilliancy but possesses substance: should come to something (I can't say what) in the finish." Then suddenly he laughed. "All the foreign mail comes the same day. I did not tell you I got a copy of the Star—London Star: it contains a notice of me drawn out by Herbert's picture in the Grosvenor Gallery." Here he paused and laughed again most merrily. "And it is very funny: the fellow who writes the notice (a very good notice it is, too: among the best)—Clarke—William I take it—says the picture is much like and all that except that Walt Whitman has no Italian curls in his beard: 'Italian curls' he calls them. How cute! How direct!

A PAGE FROM AN OSCAR WILDE LETTER TO WALT WHITMAN

to me there. Everybody's been so in the habit of looking at Wilde cross-eyed, sort of, that they have charged the defect of their vision up against Wilde as a weakness in his character." I told W. Harned liked Old Age's Lambent peaks "a whole lot." He replied "So do I, if I may be allowed to say it: to me it is an essential poem—it needed to be made." Said he "had a letter from Rhys."

"He is off in Wales somewhere or was—having a good time, flitting about, seeing his own people, new things, fresh incidents. But he says nothing about our fellows—about the fellows we are interested in over there." Again: "I have another letter, too—from Rolleston: you know him?—he is the Epictetus man. He says he has in hand now a batch of the German proofs for the German edition of Leaves of Grass. You remember, the edition is not to be complete, to include all: is simply to be made up of translations of a few of the poems—Knortz, Karl Knortz, rendering a number and Rolleston doing the rest. What will the book come to, do you think? It excites my curiosity. I want your father to see the proofs if they are sent me—want his opinion." Rolleston asked for Knortz's present address. W. says of Rolleston: "We have never met but he has made me from time to time notable tenders of affection." Said of Rhys: "He has many solid, estimable qualities: lacks brilliancy but possesses substance: should come to something (I can't say what) in the finish." Then suddenly he laughed. "All the foreign mail comes the same day. I did not tell you I got a copy of the Star—London Star: it contains a notice of me drawn out by Herbert's picture in the Grosvenor Gallery." Here he paused and laughed again most merrily. "And it is very funny: the fellow who writes the notice (a very good notice it is, too: among the best)—Clarke—William I take it—says the picture is much like and all that except that Walt Whitman has no Italian curls in his beard: 'Italian curls' he calls them. How cute! How direct!

Harned tells me Gilchrist on his call last week criticised the Eakins portrait "generally if not sharply." W. asked me: "Do you know exactly what he said of it?" adding without waiting for my answer: "But it's of no importance: of no importance at all what he thinks of it"—then saying rather apologetically: "I should not say that—should not say of no importance: it has an importance—an importance its own: has the sort of value which goes with the usual, the commonplace—as telling what technique purely, the schools, traditions, would say of such a piece of work." My father had said he was not entirely satisfied with the flesh of the portrait—it lacked in purity. W. replied: "It is good to hear that and it is in effect true I have no doubt. My own impression summed up is, that the painting is a genuine piece of work—a quite extraordinary piece of work: may one day be considered (as somebody has said here to me) even a great production. I can very easily see why the average run of critics should make faces at it—some of 'em hideous faces—why it is inevitable, necessary, for them to do so, considering their philosophies of style: but Eakins is not the man to be choked off by a few unripe or over-ripe dissenters." He said after another pause: "I am much mystified anyhow by Herbert's visit at this time. No doubt he has a big egg to crack and will crack it—but what it is, what it will all amount to—there I'm stuck."

Has sent the Hicks piece off to the Herald. Asked for my Holmes life of Emerson. "I have never read it but I should." "Morse says it's a better life of Holmes than of Emerson." "Good! That's more than likely—far more: and that's a thing that might just as pertinently be said of Herbert's picture: if it don't give me it gives Herbert. Often enough an artist floats out into his picture to the utter destruction of his subject." The Star quotes a post card recently received in England from W., who guessed it belonged to Rhys. W. read some proofs of Annex pages today. I went back a day or two to remind W. of the Rossetti letter. He said: "Read it to me: let me hear it again: I get a heap from letters, things, as I sit here, you reading, I just listening. It's getting to be a delicious lazy habit with me: you are spoiling me." I read. London, 5 Jan., 1886. Dear Whitman, I received your note of 30 November, and have been intending to write for some little while past. You and I have both suffered a loss in the death of that admirable woman Mrs. Gilchrist—a strong, warm nature, full of sympathetic sense and frank cordiality. I look round the circle of my acquaintance for her equal. Much might be said on such a topic: but often a little is as good as much. The subscription has continued going on, in much the same course as previously, as you will see from the enclosed list. In the Athanaeum (and I believe Academy) of 2 January a paragraph was put in, to serve as a reminder to any well-wishers: perhaps it may be expected that a few will respond, and that we may then regard our little movement as wound up. I shall always esteem it a privilege to have borne my small share in testifying the respect and gratitude to you which are due to you (I might say) from all open-minded men and women in the world—and from the shut-minded too, for the matter of that. My wife and children are away at Ventnor (Isle of Wight), as the London winter threatened to be too much for my wife's delicate chest. I expect to join them within the next few days, staying away some three weeks or so. As I may be a little hurried these last remaining days, it is possible that I may not just now pay in the £23. 16. 6 shown in the enclosed list—assuming as I do that this point would not be regarded as material. However, the utmost likely delay would not be long. I have seen three or four times Mr. Charles Aldrich of Webster City, Iowa: he told us of his interview with you shortly before he crossed the Atlantic. We liked him, and would gladly have seen more of him: but this apparently will not be, for he must now be just about to sail back from Liverpool to New York. Yours always truly, W. M. Rossetti.

W. said: "Rossetti is the kind of friend who never forgets the market basket: he does not bombard the needy with affectionate regrets—he feeds 'em. This is to say nothing, either, of the spiritual quality of his succor." He said: "Charles Aldrich is my good friend: he has ideas, faiths, which lead him affectionately my way. Rossetti mentions Mrs. Gilchrist. Well, he had a right to—almost as much right as I had: a sort of brother's right: she was his friend, she was more than my friend. I feel like Hamlet when he said forty thousand brothers could not feel what he felt for Ophelia. After all, Horace, we were a family—a happy family: the few of us who got together, going with love the same way—we were a happy family. The crowd was on the other side but we were on our side—we: a few of us, just a few: and despite our paucity of numbers we made ourselves tell for the good cause. These letters get me talking, don't you see?" I thought this a good time to read the Trowbridge letter to him. He did not object—in fact settled himself comfortably in the chair to hear it.

Somerville, Mass. Jan. 6th, 1865. My dear Friend.I have been thinking much of you lately and wondering where you were (for I heard some time since that you had left Washington), when the New York Times came, with your long and interesting communication. I do not yet, from reading that, understand very well where you are, and I send this at a venture. If this reaches you, please let me know your address, and I will try to send you something to help along your good work. I sent you, some time last summer, by private hands, a copy of Great Expectations and two dollars in money, but could never learn that they reached you: did they? How are you now?

A great change has taken place in my life since I saw you. My dearest friend has left me leaving in her place a little boy, now eleven months old. A superb little fellow (although I say it); and in him I have great comfort.

I went three times to find Dr. Le Baron Russell, with your note in my hand, but failing each time, I gave him up.

I am now trying to withdraw from the arena of popular literature: only the necessity of coining a livelihood has kept me in it so long. I feel that, if I live frugally and sincerely, and do not use up my mental energies in rapid writing, I may be able to do something excellent. I am about getting out a volume of poems—or, as you would say, prettinesses.

Sincerely your friend J. T. Trowbridge.W. asked as I concluded: "Is that all? It's good enough to be more. Trowbridge has had his knock-downs—bad ones—but he has always managed to get back on his feet again—to recover his mettle. He'll never set the world afire with his stories and poems—especially the poems (he puts the word 'prettiness' in my mouth, talking about them, you noticed) but he has a quite inimitable talent which I am led to believe within its own range and as subserving its own purpose amounts to a mastership. Trowbridge has a human side of which I am very fond. He took a real interest in my hospital work—contributed to it with more than words—with more than literary compliments. In these later years I have sometimes suspected Trowbridge is not quite so well satisfied with me. He says nothing to make me feel that way—except perhaps his saying nothing at all."