Sunday, September 16, 1888

Sunday, September 16, 1888

W. woke up this morning feeling bum, but rallied a little towards noon. Very close, oppressive, today. Sat in a chair eating some grapes when I entered (1.15 p.m.). "I have been frugal today." Then he added: "Sit down—get that chair and bring it here." He resumed eating his grapes. "Tom just left: he went to church this morning: Corning spoke on formalism, tradition, and what is the opposite of that: a fruitful subject: and Tom says the sermon was good. But—the best sermon is a bit (more than a bit) doubtful to me." Took him the supplementary volume Emerson-Carlyle correspondence. "I am mighty glad to get the book: it fits in with my present mood." Had been reading Hugo (translation: Canterbury Poets): "He always appeals to what is deepest in me." He is gradually gathering his books about him again—getting them from down stairs, the other room, &c. Reads miscellaneously, "to kill time," he says. Told him I had written Kennedy this morning speaking of W.'s ups and downs. He said: "I don't know what will come of it: but this much at least, is settled—we will get the books out: we have won that much." He proposed sending As a Strong Bird to Myrick. The books were piled in the next room on the shelf. I offered to get a copy. W. expostulated: "No—I will do it: I can my hand right on it: and it always does me good to move about a little." Took up his cane, rose painfully, and crossed to the other room alone. Upon getting back to his chair he wrote in the book: "Mr. Myrick, from Walt Whitman, Sept: '88." "Give him that: he should have it, something, from us: I want him to know I respect and love him."

W. questioned me searchingly about the George meeting I went to last night. "What did George say? Was he outspoken?—no hedging?" And after my replies: "Good for George! It's a fine thing to have a man talk straight instead of crooked: you must have enjoyed it. I think George must be right: I, too, for example, feel that with free trade—absolute free trade—war would be less frequent—would perhaps stop: and what a universal step ahead that would be!" W. asked what books I had home "connecting in any way with Emerson, Thoreau, and so forth." I spoke of several. "A mine! a regular mine! I shall have to make drafts upon it!" Asked particularly for Sanborn's Thoreau. "I may have read it but I think not. You see I am daily going out on new voyages of discovery." He said after a bit during which we sat quietly without a word: "I have decided to have the title pages as you suggested: the three, each dropped to the center—then a main page, enclosing all. As you say, that would unify the volume. As to what the general page should be, I must have a set of the sheets in my hands before I can fully make up my mind what to do."

W. said to me: "I like your interest in sports—ball, chiefest of all—base-ball particularly: base-ball is our game: the American game: I connect it with our national character. Sports take people out of doors, get them filled with oxygen—generate some of the brutal customs (so-called brutal customs) which, after all, tend to habituate people to a necessary physical stoicism. We are some ways a dyspeptic, nervous set: anything which will repair such losses may be regarded as a blessing to the race. We want to go out and howl, swear, run, jump, wrestle, even fight, if only by so doing we may improve the guts of the people: the guts, vile as guts are, divine as guts are!" I said to W.: "Neither do you refuse praise." "No—why should I? I am willing to have praise that belongs to me but I would not go out of my way to get it." "Isn't there something higher even than honest praise?" "You mean appreciation? Yes—that is higher—that is the highest of all." We talked a little about an old letter from Rossetti:

5 Endsleigh Gardens, N. W. 13 November, '85 Dear Whitman,I read with great concern the statement in your note of 20 October that you are "in poorer health even than of late seasons": it would give me and others the sincerest pleasure to receive pretty soon a statement to the reverse effect.

Since I wrote last to you little sums have been accumulating in my hands: I enclose an account of them, amounting to £31:19. Within the next few days I shall take the usual steps for postal remittance of this amount, and will send you the papers.

In the letter of Miss Agnes Jones to me (more especially) there are some expressions which I think you will be pleased to read. I don't know this lady: she writes from 16 Nevern Road, Earl's Court, London.

"The necessities of persons one knows, and may be bound to do all he can for, are so near and pressing that to give money to help on the efforts of those who try to realize one's ideals is seldom possible; and, even in sign of one's gratitude to one who has partly reformed our ideals, is less so. . . . Yet Walt Whitman should have those to whom it is at once instinct and natural inevitable duty not to count any cost, or weigh this claim with that; but to break the alabaster, and pour the ointment, with no thought but of him. Has he not? This is a long apology for sending five shillings: it seemed so poor and ungenerous to send, unless I had said what gratitude it may yet stand for. Walt Whitman knows better than most that the sense of spiritual gain can seldom find the expression it longs for; and that it may forever remain unexpressed in material terms, and yet be present and abiding. I have so often wished to thank him."

I grieve to say that Mrs. Gilchrist has been much out of health of late, and I fear still continues so. No doubt you have details from headquarters.

Yours in reverence and affection, W. M. Rossetti."That is in a sense a woman's letter," said W. "Though the women are by no means always on my side, when they are they are. I like Rossetti's signature: 'yours in reverence and affection'—especially the 'affection.' Leaves of Grass is essentially a woman's book: the women do not know it, but every now and then a woman shows that she knows it: it speaks out the necessities, its cry is the cry of the right and wrong of the woman sex—of the woman first of all, of the facts of creation first of all—of the feminine: speaks out loud: warns, encourages, persuades, points the way." I broke in: "And marriage? What of marriage?" "I don't know what about marriage (the state, the church, marriage) but about love—well, love will always take care of itself: it does not need censors, monitors, guardians." "And free love?" "Why—you are catechizing me! Free love? Is there any other kind of love?" "Would less law mean less responsibility?" "No—more: more responsibility."

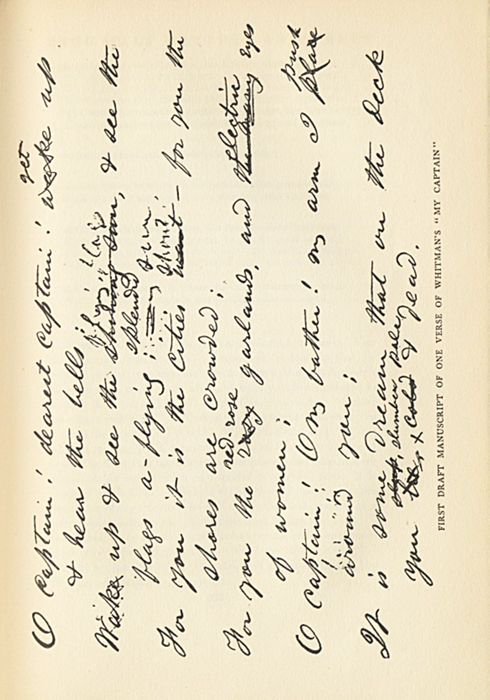

W. is very familiar with the formal classics in a general way. In our talk today he referred at different times to Aristophanes, Plato, Socrates, Marcus Aurelius, the Bagavad Ghita, Euripides, Seneca. Once he quoted the Bible. He also advised me to read all I could "in Buddhist and Confucian books," saying: "Tackle them anyhow, anyhow: they will reward you." I had a pink in my button hole. He called me over to him. Took the flower. "You let me have this," he said: "you don't need it: you are going out into the open air: leave it to me here in my prison: it is a ray of light." He stuck it into the lapel of his own coat and slanted his eyes down affectionately towards it. Day hot. "It is close—sultry: I make the best of it. I seem to have a journey to make: I push on—push on. There is a journey's end: it does not appal me." He said again: "Don't forget the Jane Carlyle. And the printers—well, use your judgment with them: they are rather in your hands than mine." I kissed W. as I left. He seemed very grave. "Some kiss some day (maybe some day when we both least expect it) will be the last kiss. Good bye! Good bye! God bless you!" I find the My Captain manuscript W. gave me Thursday to contain some variations. I will copy it here literally without argument.

My Captain

The mortal voyage over, the gales and tempests done, The ship that bears me nears her home the prize I sought iswon, The port is close, the bells I hear, the people all exulting, While (As) steady sails and enters straight my wondrous vet-

eran vessel; But O heart! heart! heart! leave you not the little spot, Where on the deck my Captain lies—sleeping pale and dead. O Captain! dearest Captain! get up and hear the bells; Get up and see the flying flags, and see the splendid sun, For you it is the cities shout—for you the shores are crowded; For you the red-rose garlands, and electric eyes of women; O Captain! O my father! My arm I push beneath you; It is some dream that on the deck you slumber pale and dead.

FIRST DRAFT MANUSCRIPT OF ONE VERSE OF WHITMAN'S "MY CAPTAIN"

My captain does not answer, his lips are closed and still,

My father does not feel my arm—he has no pulse nor will;

But his ship, his ship, is anchor'd safe, the fearful trip is done,

The wonderous ship, the ship divine, its mighty object won,

And our cities walk in triumph—but O heart, heart, you stay,

Where on the deck my captain lies sleeping cold dead.

And cities shout and thunder—but my heart.

And all career in triumph wide—but I with gentle tread,

Walk the deck my captain lies, sleeping cold and dead.

My captain does not answer, his lips are closed and still,

My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will,

But his ship, his ship is anchor'd safe—the fearful trip is done,

The wondrous ship, the well-tried ship, its proudest object

FIRST DRAFT MANUSCRIPT OF ONE VERSE OF WHITMAN'S "MY CAPTAIN"

My captain does not answer, his lips are closed and still,

My father does not feel my arm—he has no pulse nor will;

But his ship, his ship, is anchor'd safe, the fearful trip is done,

The wonderous ship, the ship divine, its mighty object won,

And our cities walk in triumph—but O heart, heart, you stay,

Where on the deck my captain lies sleeping cold dead.

And cities shout and thunder—but my heart.

And all career in triumph wide—but I with gentle tread,

Walk the deck my captain lies, sleeping cold and dead.

My captain does not answer, his lips are closed and still,

My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will,

But his ship, his ship is anchor'd safe—the fearful trip is done,

The wondrous ship, the well-tried ship, its proudest object won; And my lands career in triumph—but I with gentle tread Walk the spot my captain lies sleeping pale and dead.

When I spoke to W. about this manuscript he said: "You don't like the poem anyway." I explained: "I don't say that. I think it clumsy: you tried too hard to make it what you shouldn't have tried to make it at all—and what yon didn't succeed in making in the end." W. laughed and responded: "You're more than half right." "Technically it conforms neither to the old nor new: it is hybrid." W. laughed and said: "If you keep on talking you'll convince me you're the other half right also! The thing that tantalizes me most is not its rhythmic imperfection or its imperfection as a ballad or rhymed poem (it is damned bad in all that, I do believe) but the fact that my enemies and some of my friends who half doubt me, look upon it as a concession made to the philistines—that makes me mad. I come back to the conviction that it had certain emotional immediate reasons for being: that's the best I can say for it myself." On the reverse side of the two sheets of paper containing the My Captain draft was this stanza:

And by one great pitchy torch, stationary, with a wild flame,and much smoke, Crowds, groups of forms, I see, on the floor, and some in the

pews laid down; At my very feet a soldier, a mere lad, in danger of bleeding to

death—(he is shot in the abdomen,) I staunch the blood temporarily, (the youngster's face is

white as a lily;) Then before I depart I sweep my eyes o'er the scene around,

—I am fain to absorb it all, Faces, varieties, postures beyond description, some in ob-

scurity, some of the dead.

W. quizzed me: "I guess you like this better than My Captain." I asked him: "Shall I lie to you or shall I tell you the truth?" "You needn't do either: I know anyhow: you do like it better." He stopped as if for me to say something. I didn't. Then he smiled and added: "I like it better, too—but you mustn't tell on me."