Sunday, October 28, 1888.

Sunday, October 28, 1888.

7.45, evening. W. reading Tribune. Had "passed an average day." Ate well. Harned had brought in The Tribune. I had the November Scribner's along with me. Instantly looked over the Sheridan paper—From Gravelotte to Sedan. Exclaimed over the frontispiece: "What a strong, a beautiful, picture!" Tried to interpret the decorations: "This is an army corps, this is probably foreign," and so on until he finally said: "I guess I know very little about it anyhow." He spoke of the portrait of Arnold that went with the Birrell essay. Would he read the essay? "Perhaps—it may occur to me to do so: it may occur to me: I would have no original impulse to do it: would not deliberately start out to read anything more about Arnold." Looked at the portrait again—shook his head: "No, no—he was not for me: yet he must have been because he was: there is no better reason, and no worse: indeed, that is sufficient."

W. told me that he had "sent a McKay book to Doctor Bucke," adding: "I sent it off to-day: Musgrove just a short while ago took it up to the post-office." Then spoke of my copy. "Won't you take it now? Yes, take it now." I picked up a book and took it over for him to sign. "What shall I put into it? You don't want your own name? You will want to give it to somebody?" I replied, laughing: "Well, put my girl's name in it then: she comes next, anyhow"—W. interrupting and shaking his pen at me—"or first!" proceeding then to write in the freest hand: "Anne Montgomerie from the author W. W. Oct: 28, '88"—and concluding: "She's as sweet and dear as an unsoiled flower: I'm sure she comes first." Then he said: "That was not all I sent Bucke: I wrote him a postal—also forwarded some papers: the North American you brought me—then the Times: you saw the Times yesterday? It contained a notice—so much of it, perhaps"—indicating a few inches on his coat sleeve—"half a column, maybe. All the critics say about the same thing just as if they consulted together and agreed to: one fellow starts so and so—they all follow. The North American man has evidently written without reading the book: he is markedly sophomoristic: I am sorry for anybody who thinks he ought to read it." Then with a twinkle in his eye: "But they are all good from the publisher's point of view: they say that Dave McKay is the publisher—that he lives and publishes in Philadelphia—that the book is so much per copy—and all that: so you see the newspapers are not without a market importance. I object to the harping all around on my sanity, sickness—such things: it is remarkable, Walt Whitman has lived all these years and is still sane: it is a miracle, Walt Whitman has been sick and sick and sick and has managed not to die: he is a wonder, this old old man, who has saved his soul from the raging decay of the body: such things, again and again copied, repeated. Why should they come in at all? What have they to do with the real question, which is whether the book is a book and deserves respect as such?" I read this to W. from the New York Home Journal:

"Walt Whitman's new volume of poems, November Boughs, is another proof of the fact that advancing age does not necessarily imply decay of intellect. Mental activity is indeed the surest buckler against senility. Some of these poems might have been written in the full vigor of manhood. The aged poet seldom leaves his room, but he receives kindly care and attention from many friends, one of whom, Mr. Horace Traubel, is in daily attendance."

He said: "There it is again: wonderful old man: hi there Walt—think of it: you're entitled to be an idiot but you're some punkins! Yet I like the paragraph on the whole: it sounds well: is very friendly, circumspect: and see that one sentence there: 'Some of these poems might have been written in the full vigor of manhood!' That sounds better than an excuse—better than 'it's pretty good considering'—and so forth." Again: "Some of the many who used to fling their darts at me have of late been silent—holding in: whether for good or not I hardly know." "Have they changed their opinions?" "No—not at all: their silence is from policy." I asked him about The Critic. I do not count upon it as any too neighborly or affectionate though it is by no means unfriendly. I think Joe Gilder takes the business view of me entirely: if I succeed, if I sell my books, good for me, approved!—if I do not, bad, bad! Yet I trust Joe: I imagine his paper has a hard tussle to get on: indeed, I am surprised it lasts at all: it is kept up on a pretty high plane where everything like popular support is out of the question: they might vulgarize it and make it pay but they won't do that. It is Jennie Gilder, the girl on the staff, who is more friendly to me—more likely to decide doubts in my favor." "Your note did not appear in their issue of last week." "Ah! perhaps it will not show up at all: Joe may decide not to use it—that it is not exactly what he wants. I wonder, I wonder?"

W. has prepared lettering for title page, wiping out the last ornament—two stars, one on each side of "complete." Wrote these instructions to the printer in the corner: "Abt like this. I leave however mainly to your taste and judgment—I want to see proof—pull two impressions—I want your pressman to keep up as good a strong color as can be maintained without clotting or muddy." More favorable letter from O'Connor to-day. "He is cheerful: has not yet regained control of his eye-lid: how that recalls Heine—Heine the wonderful! William speaks of 'a week'—expects a change in a week—is still having battery treatment. He is cute—knows what may come—may defy the prediction of the doctors—Bucke with the rest." Then, after

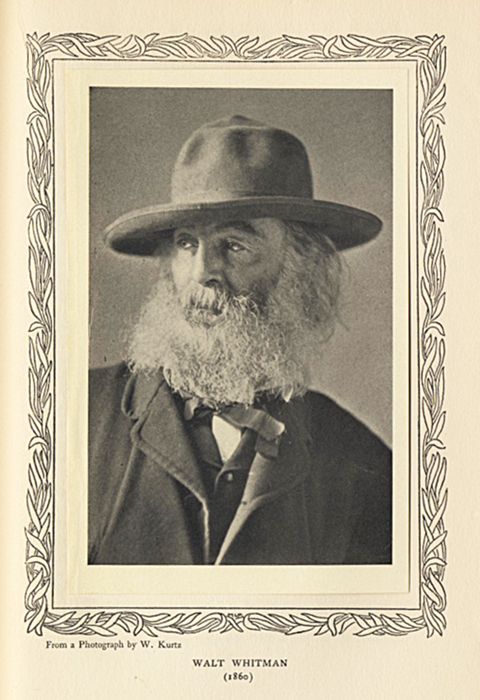

From a Photograph by W. Kurtz

From a Photograph by W. Kurtz

Walt Whitman

(1860)

a pause, as if to qualify his speech: "At least, we hope so." Remarked O'C.s "imperturbable spirit:"

"He keeps it up—his letter is full of life: why, he is still joking, making fun: probably will make light of his danger to the very last."

Showed W. Olive Dana's article on Stedman, with portrait. "It appears to be intelligently written," said W., "and this portrait resembles him fairly. Stedman is of good size—not large nor heavy—not small. I have every reason to regard Stedman with warmth, acceptance, even affection: he is truly good to me: effusive, almost: seeks to be of service, to prove his faith: is open, transparent, genuine." "Indeed," he asked, turning his eyes up to mine (I was over his shoulder): "Don't you think this picture bears me out?" W. added, again: "Ed is the best talker of the lot—readiest. It's not that he says bright things: not that particularly: but readiest—readiest to say what forces its way up. He is popular—popular as a man—everybody likes him: you would: you would want to be with him: in a sense he has the fine spirit of the camerado." I alluded to John Burroughs' statement while here that Gilder and Stedman were "coming over," W. responding: "Did John say that? He did not say it to me, or at least if he did I did not pay the right attention to it at the time. I do indeed see the drift that way in Stedman though not so positively in Gilder, whose human feeling towards me, noble brotherly feeling, I cannot question. John seems a little afraid of me, if I may say it: seems afraid I have done something or may do something to offend them. I remember at the time Stedman had that long piece in the Century he appeared to have caught the idea—I was told so, told by several—that I was mad: had trodden him under foot, so to speak. I was always troubled over this rumor. Nothing could have more misrepresented me. I regarded the piece as thoroughly friendly, thoroughly courteous, thoroughly fair—if not more. It is clear to me still: I had it in my mind at the time (did not say it, probably, to anyone: I don't think to John: I know not—certainly not—to Stedman): I don't care this"—snapping his fingers—"what any of them think, this way or that. Yet all my feeling was in good temper. It had been free criticism and I never resent free criticism—in fact, no man has had more of it, no one has held himself so open to it—and I may add that I have got some of my best points from it. I am only too glad to be read and examined as Stedman has read and examined me. After a long experience with men who neither hoped for truth nor would see it, it was like daylight to meet with such treatment as Stedman accorded me. I have an appreciation of Stedman that does not require me to put him into the seventh heaven of flattery."

Speaking of Bucke's book, Man's Moral Nature, W. said: "It is a grapple: I find it tough up-hill work. I can see how valuable the book should be to anyone who is interested in such studies, as I confess I am not." W. handed me a couple of old Burroughs letters with the remark: "You may find a way to make these fit in with your collection: if you can't there's another thing you can do with them: do that." I said: "You wouldn't give them to me if you had the slightest notion that I would do that other thing." Laughed roundly. "That's so: I wouldn't." I looked at the letters: said: "There's a lot of difference in the handwriting of the two letters." One was dated 1864, the other 1886. "Yes: John originally wrote a hand like a boarding school miss: his hand has grown strong as it has matured." I sat back on the bed and read the letters—this one first:

Treasury Department, Washington, Aug. 2, 1864. Dear Walt,I am disconsolate at your long stay. What has become of you? On returning the 7th of July I found you had gone home sick. You have no business to be sick, so I expect you are well. I was so unlucky as to be sick all the time I was home—and most of the time since I came back. I am quite well now, however, and feel like myself. Benton and I looked for you at Leedsville, as I wrote to you to come. If you have leisure now you would enjoy hugely a visit up there. I hope you are printing Drum Taps, and that this universal drought does not reach your "grass." But make haste and come back. The heat is delicious. I have a constant bath in my own perspiration. I was out at the front during the siege of Washington and lay in the rifle pits with the soldiers. I got quite a taste of war and learned the song of those modern minstrels—the minnie bullets—by heart. A line from you would be prized.

Truly yours, John Burroughs."How excellent that is," said W.: "'The heat is delicious: I have a constant bath in my own perspiration.' I know what that means. Times have changed: now I dread what then I rejoiced in: I am afraid of the severe heat—it subjects me to an awful strain. 1864! A quarter of a century almost come and gone since that was written! Do you notice John's ladified hand of those days? Now his writing has a grip on itself: it stands for something creative—for the grown John—for the master, not the pupil, of experience." Burroughs' other letter was this:

West Park, N. Y., April 3, '86. Dear Walt.I received the books all right, also your letters and card. I am just back from Roxbury where I went a week ago to make sugar in the old woods of my boyhood; had a pretty good time, though too much storm. Only my brother is now upon the old farm. I have to go back there at least twice a year to ease my pain. Oh, the pathos of the old place where my youth was passed, where father and mother lived and died, and where my heart has always been.

I have been pretty well since I saw you, except that I have been off my sleep a good deal. Just now I am having a streak of sleeplessness. I do not quite know what to make of it. Today is my birthday, too; I am forty-nine today. I hope spring finds you better. I lately heard from you through J. W. Alexander, the artist. I think he will make a good picture of you. He is a fine fellow. I am glad to hear of the projected new book. I hope it is to be a reality. Your title is good. My book, Signs and Seasons, will be out this month. I do not think much of it—the poorest of my books, I think. No news with me. I hope to see you in May, as I go to Kentucky. I hope you will not try to face the summer again in Camden. It is very imprudent. A bright afternoon here with remains of last night's snow still lingering.

With much love J. Burroughs."There is a little of the let-us-cry character about John's letters," said W.: "you would never catch William standing in any such attitude of apology towards life: his acceptance of life is always vehement and conclusive: I always feel in William's presence (in the presence of one of his letters, too) that I have the best right to live. It is always wonderful to me—the inexhaustible fund of his energy. Sick or well, sad or glad, William is the same man—cheerful, tonic, like a strong wind off the sea. John is rather more of the contemplative type—is quietistic (too much so, I should say): is a trifle too conscious of his ills. It takes more than a few kinds of people to perfect a world, don't it? That's how we get in—eh, Horace?" "Good night" after that and I slid out.