Tuesday, December 4, 1888.

Tuesday, December 4, 1888.

7.45 P. M. W. lying down—not, however, asleep. Shook hands. Seemed cheerful but weak. I started to ask him how he was. He stopped me. "Nothing more till you tell me how is the mother? how is the boy?" of whom a very favorable account indeed: he saying: "That is all good to hear—that is what I want to hear—delight in"—and again: "What a precious body Mrs. Harned must have!" "The picked of many," he thought it. Notable how motherhood appeals to him. After this he would talk about his own condition. Explained: "I woke up feeling much improved—spent the morning well: but this afternoon, this evening, I seem bad as ever—the tide back again. Yet I am thankful for the relief, short though it was. I am hoping, if not believing, that this trouble of the gland—what they call the prostate gland—may shortly be ended: the Doctor has not been over: this is not his day: to-morrow. I can say one thing: I spent a tolerably good night: it rested me." But he was very feeble. After awhile he wanted to get up, go to his chair—did so. He mainly desired to do these things for himself: started so this evening, I walking by his side; he was unsteady—reached out for me. When finally in his chair he at once again revived—seemed like his usual self. He had written a label for a package of a hundred more first sheets which he knew I wished to take along with me. When my bundle was ready he produced this from the table—pasted it on. "It is almost a superstition. I did it for myself when I would start out with a package—always addressed it." Alluded to the books: "I like the sample so much: it seems such a stroke: I want Oldach to follow it exactly—not a change: I have decided to have one hundred and fifty done: a hundred and fifty instead of a hundred: at first it was fifty, then one hundred, then a hundred and fifty. I was eligible to be pleased with this success." Oldach had written note received to-day for more first sheets and more labels. "I sent word over by Ed that the labels had not come but would be sent to-morrow: since that I have received them: I will get you to take them and the sheets over: I have written Oldach a note: you can see what it is."

Camden, Evn'g: Dec: 4, '88. Mr. Oldach BinderSir I will have 150 (not 50 nor 100) copies bound in the style I like—as sample.—I send 100 autograph sheets—(50 were sent before.) I send 100 labels—(50 were sent before.) The sample made up is herewith—partly as sample which all copies will be compared strictly by—and partly to put in the right page for "Specimen Days" title back'd with the copyright line, wh' in present is out (the printer's fault) endangering our copyright. Please see the right ones get in these copies.

Walt Whitman.W.'s note was written firmly in pencil. I am daily with Oldach—sometimes talk with him over the 'phone. W. interested—questioned me: "You can hear quite well?" I asked: "Have you never tried?" "Never—never once." Afterwards: "It is a wonderful servant—now become necessary, probably: I have been thinking a good deal about what Brinton said since you told it to me: the more I turn it over the more weighty his reason gets." As he sat there by the light he asked me suddenly: "Have you read the President's message?" "No." "Neither have I: not a word: nor shall I." It was long: he was "not in condition to tackle it." Then: "I remember how when I was a young fellow I followed the great magazines—came upon them in one place or another: the foreign reviews, quarterlies: they gave the most splendid compendium of new books, things, events—the information by short cuts. To a fellow who could n't get the books it was invaluable. I realize the danger of trusting too much to reviews of any sort—even mere statements of book news being subject to bias, where criticism is not intended. But, allowing for that, the compendium was invaluable." Sometimes the newspapers attempted the thing, "but only rarely." "The Ledger, for instance, practised the system years ago—does it still: there were years—five or six years—when I never missed The Ledger—always read its compend of news. It seemed to me very effective, valuable, with something more in the case of The Ledger—a sort of judicialness, a desire to be fair, to state the whole of a case." A letter from Bucke. "There is no change in things there—news, none: the meter resting: snow, melt, slush, mud—a general air of dullness: that is Doctor's report." Said that he had been a little more active to-day.

Ed alleged W. "was at work again," &c. Read papers (always tries to do that)—"Frank Leslie's, Press, &c.: later, the local papers." Then, as he said, had "written a trifle." "I took Alexander Gardner's sheet—the title page: it had quite a good deal of white paper: wrote a long note on it—a note of my personal affairs—and, as is my habit, made it a sort of combination matter: sent it to Kennedy with request to send to Burroughs with request to send to O'Connor with request to send to Bucke." It "considerably eased" him "to be able to write this": he "could not have written to all"—yet "felt all would like to hear." "I calculate it will go around promptly—Kennedy get it to-morrow, Burroughs Friday, O'Connor Saturday evening, Bucke early in the week. Then they all have the ripple, if so to be called, of seeing the Glasgow edition—of following up the changes in that edition." Then he pursued the matter in this way: "How about that Alexander Gardner—who is he? I have been asking myself that question all day: he is the bookman probably in that part of Scotland. Could he be the Alexander Gardner I knew in Washington—immigrated, gone home? Oh yes! My Gardner was a Scotchman—that is the point: he was the man who took the Washington picture I gave you: he took a number of pictures of me—some of them extremely good." Nor was Gardner a mere chance non-literary friend. "He went strong for Leaves of Grass—believed in it, fought for it. If you can picture to yourself Hunter as a young man, you may get some little idea of Gardner: Gardner was large, strong—a man with a big head full of ideas: a splendid neck: a man you would like to know, to meet." W. could not "recall many of the portraits" taken by G.—the multiplicity of pictures is so confusing." "He did not take the picture Herbert used for the etching, but he took the picture you have." I remarked: "I would not swap that picture for any other." W." "Nor would I: it is one of the best if not the very best."

I received Bucke's letter of the 2d to-day, answering my first report of W.'s new complication. Expresses great anxiety. Matters look dubious. W. perceptibly growing weaker. Must rally some or rapidly decline. Says himself: "This is not life—this is only half a life: it 's a fighting half—but only half anyway." I asked W.: "What about the Bad Gray Poet? You told me to remind you of it." "O yes: so I did: I had it in mind to say something to you about it: initiate you into its history: the devilish insistent thing has gone about so far: it means so little yet it is made so much: are you sure you don't know anything about it?" I was quite sure. I had seen a fling here and there but I had set it down to the general malice of his libellers. W. said: "No—no: it 's not that—not that alone: there 's something to this story—just enough to make it plausible to my enemies—to those who want to discredit me." I put in: "They have said debts—debts: as if there was more than one debt: as if you made a habit of not paying your debts." He smiled at that. "That 's what you would call a blanket charge: I make nothing of that: but there is one particular debt which is the single basis for all these insinuations." That was news to me. "Yes," said W.: "one single debt: it was a matter between me and James Parton: I thought it was all settled to the satisfaction of every one concerned very long ago: I thought so: but every now and then a new accuser appears—some variation crops up: I am again charged, convicted, sentenced." To what did he ascribe the persecution? He said: "Do you call it persecution? Well, it might be called that: persecution: yes: the main thing is that some one or several or many ones are still willing to repeat the story vaguely enough not to commit themselves, definitely enough to create an ugly impression: it is always put in such a way as to be unchallengeable. William was very furious about it: it was bandied about Washington—got into the papers: William asked me: Why don't you put your foot down on it? I hate controversy: hardly feel like controversially affirming or denying anything: would rather do almost anything else: but William was vehement: swore himself black and blue over it: said if I would n't why should n't I let him do it: just meet the thing with the proper rebuttal—figures, facts, and so forth, and so forth. That was William: I suppose he was right: I needed only to make a simple public statement: I would be believed." Had Parton always been responsible for this? "I don't think so: maybe: hardly: there were other elements in the story—venom, jealousies, opacities: they played a big part: and, if I may say it, women: a woman certainly—maybe women: they kept alive what I felt James Parton would have let die, left dead. Well, as I was saying, William was fiery, emphatic: drove me to do it: had me write him about the affair in detail: this I did: he must still have the document: I gave him the story—the receipts (there were receipts): William felt that a time would come when it would be in order to submit this rebuttal: a proper time—a timely time: to-day, maybe—to-morrow—in the future: he was delighted with what I gave him: he said: 'Now I am armed to the teeth.'" W. quietly laughed. I asked: "Then you say this Bad Gray Poet piece referred to the Parton debt, which was paid? That you did borrow money from Parton? that it was all settled for?" He nodded. "That 's the whole crime in a nutshell: I wanted you to know that much about it: you might get hold of the paper I gave William—might see it: you would then realize how much and how little there is to the irresponsible newspaper gossip on the subject."

I wanted to ask more but was not inclined to worry him with questions. He did say this: "I thought I would go more into items for you, but it 's not necessary: the debt was closed out: I have (William has) the receipts for it." When I left I said: "Well, Walt, you are still the Good Gray Poet to me!" He pressed my hand gently. "Oh! I had no doubt you would realize my version: I know how you look at such things: you have mixed in the battle enough to realize the quality of the antagonism by which I have been pursued: I only wanted you to know." "To know at least enough to know that there was a Good Gray Poet side as well as a Bad Gray Poet side to the story!" I exclaimed. "Yes: yes: that 's it: I don't know but I may sometimes make some record, put down some memoranda, in the matter for you and Tom."

[1910. This Parton matter came up again in one way or another in our after-talks. W. never wrote the mem. for

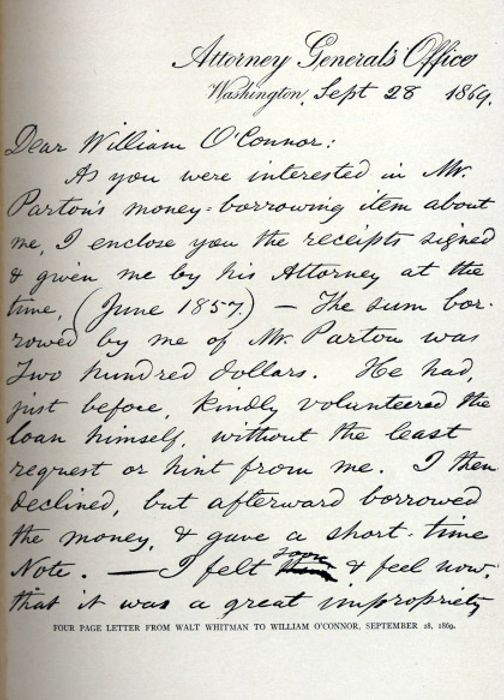

FOUR PAGE LETTER FROM WALT WHITMAN TO WILLIAM O'CONNOR, SEPTEMBER 28, 1869

Facsimile of letter from Whitman to O'Connor, Washington, 28 September 1869, page 1

FOUR PAGE LETTER FROM WALT WHITMAN TO WILLIAM O'CONNOR, SEPTEMBER 28, 1869

Facsimile of letter from Whitman to O'Connor, Washington, 28 September 1869, page 1

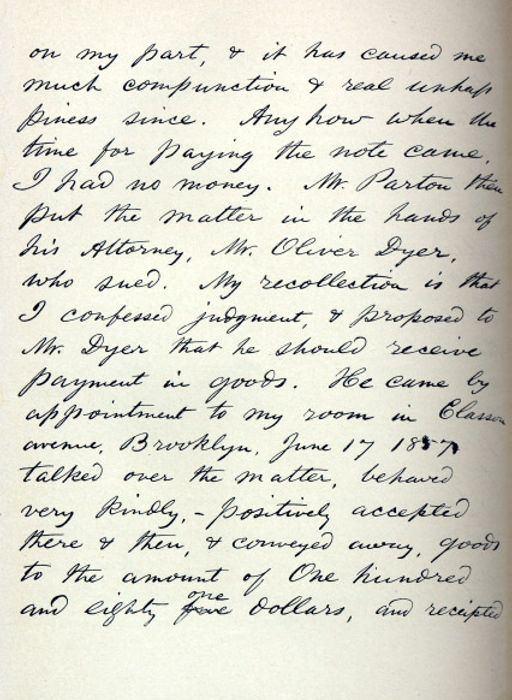

Facsimile of letter from Whitman to O'Connor, Washington, 28 September 1869, page 2

Facsimile of letter from Whitman to O'Connor, Washington, 28 September 1869, page 2

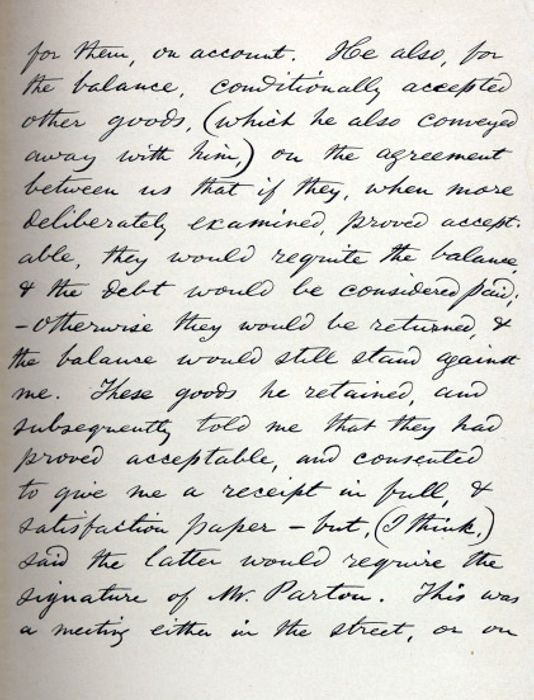

Facsimile of letter from Whitman to O'Connor, Washington, 28 September 1869, page 3

Facsimile of letter from Whitman to O'Connor, Washington, 28 September 1869, page 3

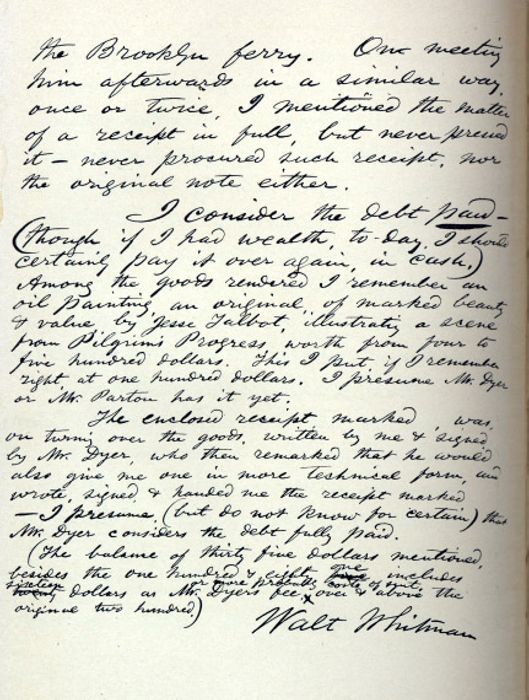

Facsimile of letter from Whitman to O'Connor, Washington, 28 September 1869, page 4

Harned and me, though he referred to it more than once. Later he said:

"It is all past and gone: it hardly seems worth dwelling upon—taking seriously—any more." But more recent writers have taken the thing seriously. I submit here the document prepared for William by W. and passed into my hands since by Nellie O'Connor.]

Facsimile of letter from Whitman to O'Connor, Washington, 28 September 1869, page 4

Harned and me, though he referred to it more than once. Later he said:

"It is all past and gone: it hardly seems worth dwelling upon—taking seriously—any more." But more recent writers have taken the thing seriously. I submit here the document prepared for William by W. and passed into my hands since by Nellie O'Connor.]

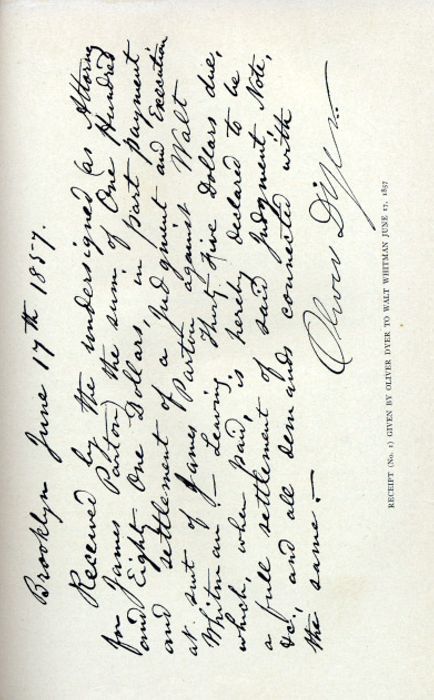

As you were interested in Mr. Parton's money-borrowing item about me, I enclose you the receipts signed and given me by his attorney at the time, (June 1857)—The sum borrowed by me of Mr. Parton was Two hundred dollars. He had, just before, kindly volunteered the loan himself, without the least request or hint from me. I then declined, but afterward borrowed the money, and gave a short-time Note. I felt soon and feel now, that it was a great impropriety on my part, and it has caused me much compunction and real unhappiness since. Anyhow when the time for paying the note came, I had no money. Mr. Parton then put the matter in the hands of his Attorney, Mr. Oliver Dyer, who sued. My recollection is that I confessed my judgment, and proposed to Mr. Dyer that he should receive payment in goods. He came by appointment to my room in Classen avenue, Brooklyn, June 17, 1857, talked over the matter, behaved very kindly,—positively accepted there and then, and conveyed away, goods to the amount of One hundred and eighty one dollars, and receipted for them, on account. He also, for the balance, conditionally accepted other goods, (which he also conveyed away with him,) on the agreement between us that if they, when more deliberately examined, proved acceptable, they would requite the balance, and the debt would be considered paid;—otherwise they would be returned, and the balance would still stand against me. These goods he retained, and subsequently told me that they had proved acceptable, and consented to give me a receipt in full, and satisfaction paper —but, (I think,) said the latter would require the signature of Mr. Parton. This was a meeting either in the street, or on the Brooklyn ferry. On meeting him afterwards in a similar way, once or twice, I mentioned the matter of a receipt in full, but never pressed it—never procured such receipt, nor the original note either.

I consider the debt paid—(though if I had wealth, to-day, I should certainly pay it over again, in cash.) Among the goods rendered I remember an oil painting, an original of marked beauty and value, by Jesse Talbot, illustrating a scene from Pilgrim's Progress, worth from four to five hundred dollars. This I put, if I remember right, at one hundred dollars. I presume Mr. Dyer or Mr. Parton has it yet.

The enclosed receipt marked 1, was, on turning over the goods, written by me and signed by Mr. Dyer, who then remarked that he would also give me one in more technical form, and wrote, signed, and handed me the receipt marked 2. I presume (but do not know for certain) that Mr. Dyer considers this debt fully paid.

(The balance of thirty-five dollars mentioned, besides the one hundred and eighty one, includes sixteen dollars as Mr. Dyer's fee, or more probably costs of suit, over and above the original two hundred.)

Walt Whitman. Brooklyn June 17th 1857.Received by the undersigned (as Attorney for James Parton) the sum of One Hundred and Eighty-One Dollars, in part payment and settlement of a Judgment and execution at suit of James Parton against Walt Whitman—Leaving Thirty-Five Dollars Due, which, when paid, is hereby declared to be a full settlement of said Judgment, Note, &c., and all demands connected with the same.

Oliver Dyer. RECEIPT (No. I) GIVEN BY OLIVER DYER TO WALT WHITMAN JUNE 17, 1857

Facsimile of receipt from Dyer to Whitman, 17 June 1857

RECEIPT (No. I) GIVEN BY OLIVER DYER TO WALT WHITMAN JUNE 17, 1857

Facsimile of receipt from Dyer to Whitman, 17 June 1857

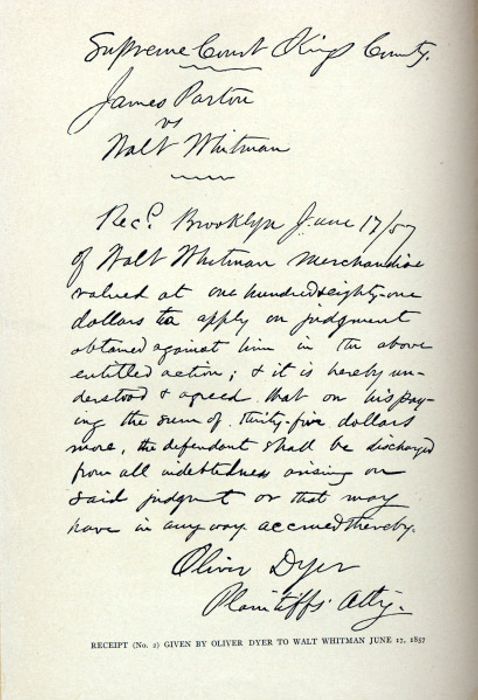

RECEIPT (No. 2) GIVEN BY OLIVER DYER TO WALT WHITMAN JUNE 17, 1857

Facsimile of receipt from Dyer to Whitman, 17 June 1857

Supreme Court Kings County.

James Parton vs Walt Whitman.

RECEIPT (No. 2) GIVEN BY OLIVER DYER TO WALT WHITMAN JUNE 17, 1857

Facsimile of receipt from Dyer to Whitman, 17 June 1857

Supreme Court Kings County.

James Parton vs Walt Whitman.

Rec'd Brooklyn June 17, 1857, of Walt Whitman merchandise valued at one hundred and eighty-one dollars to apply on judgment obtained against him in the above entitled action; and it is hereby understood and agreed that on his paying the sum of thirty-five dollars more, the defendant shall be discharged from all indebtedness arising on said judgment or that may have in any way accrued thereby.

Oliver Dyer Plaintiff's Atty.[Pencilled memo. on reverse of receipt one in W. W.'s hand] Mr. Dyer also took Jefferson's works and Carlyle's Cromwell at $9 (if he keeps them)—which would then leave $26. due as the Judgment or claim

June 17, '57 W. W.The envelope in which W. sent this material was addressed to "Wm. D. O'Connor, Light House Board, Treasury Dept, Washington City." O'Conner marked the envelope: "Parton matter." W.'s letter was written on the paper of the Attorney General's Office. Receipt one was written in W. W.'s hand on a plain slip of paper and signed by Dyer. Receipt two was written all in Dyer's hand on the reverse of a tax bill of the City of Williamsburgh.