Sunday, December 23, 1888.

Sunday, December 23, 1888.

8 P.M. W. yesterday undoubtedly better than at any time in two weeks or perhaps a month. On his bed this evening. Said of his health: "I call it a continuation of yesterday, though I don't realize it as having the same edge and nip." He at times feels almost as if he was enjoying a "revival"—"a dim suspicion of something or other" as he states it. Walsh not in to-day. W. feels that he is not needed. Digestion pretty good. The one thing he says he notices after each of these setbacks is the "weakness," and this weakness "grows and grows, each spell setting me down a peg or two." Still, he walks across the room again, often unassisted: can sit up much longer than he could a week ago: is generally more optimistic and able. Face very cheerful, calm, bright, voice strong. I had Tolstoy's Sebastopol along with me. Left it. "I know I shall like to read it." We had spoken of it before this last illness.

Out in Germantown. Mrs. Burleigh had received some fruit from the south. Gave me two tangerines which I passed over to W., who was glad, smelt of them, and said: "I will lay them aside till morning and make a breakfast of 'em." He asked me about the weather. Were the stars not full out? Was it cold? Then of my trip. Always brightens up when so humored. He said to-night playfully: "You must always answer my questions even though I don't always answer yours." I said: "You don't answer my questions—that 's true. That question about the great secret—you've never answered that." He asked: "You have n't forgotten that yet?"

"Do you want me to?"

"No." There was a pause. Then he said again: "No: I want you to keep on asking till I answer: only not to-night—not to-night." Returned

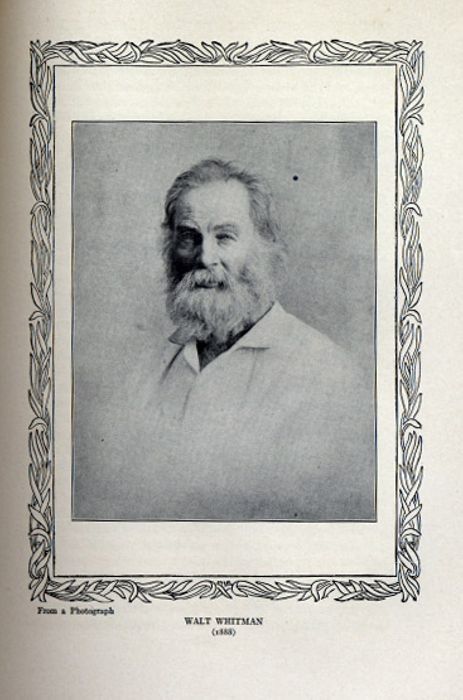

From a photograph

From a photograph

WALT WHITMAN

(1888)

Reproduction of a photograph of Whitman, 1888

me Ticknor's literary bulletin and The Stage, which I left with him last night. "I read them both: the theatrical paper all through: it is very bright: it is a great relief to hit upon that airier stuff occasionally." Said also: "I read all the notices in the literary journals—every word of them. I am very industrious at that!" Bellamy's picture in the Ticknor pamphlet. W. had forgotten all about Baxter's counsel that "Traubel" should read Looking Backward. Have not done so yet. W. urged it.

W. wrote in Ed's book to-day: from so and so to so and so: then: "Camden, New Jersey, America," contemplating Ed's ultimate return to Canada. Shows how closely he looks to details, well or unwell. Harned in early in the evening. Did not stay long. W. has struck a notion to have some of the big books boxed—perhaps a hundred of them.

Had he read De Guérin? He asked: "How do you spell the name?" then: "Ah! I know it: I have read him, somewhat—not enough, however, to have got a decided impression—an impression I retained." Spoke of "American ballade rondeau writers—their small calibre, mean aims—the mere literary hangers-on and sportsmen." "But ours are not the real fellows—even of that sort: they are the six time diluted imitators of the French: the French excel in all that: in grace, beauty, sparkle—witty sayings, bright rhymes—persiflage, they call it." There was a paragraph in The Press to-day about Tennyson's protest against the introduction of a railroad near him on the Isle of Wight. W. had not read that, "but I read a paragraph somewhere which said that he had got much better of his sickness—the acute gout, or whatever." W. did "not sympathize with such sensitiveness"—did not "fear the age of steam." "There is Ruskin: Ruskin seems to think himself constituted to protest against all modern improvements." I asked: "Are all the modern improvements improvements?" W. shook his head: "Oh you lawyer! I 'm afraid not." W. said Ruskin "maintained a more or less curious and uncertain attitude towards" himself. "I have heard nothing from him, of him, recently: years ago he was known to have read Leaves of Grass: he said Leaves of Grass contained no humor—no humor at all: it is true he saw good in it, too—acknowledged the good." He thought "the friendship that existed between Ruskin and Carlyle" was "rather remarkable if not inexplicable." Yet W. felt that "Ruskin's notions of professional integrity—in art, literature—were noble, admirable, no doubt productive of vast moral educative benefits."

No mail in to-night. "Letter form Doctor yesterday, but, as I told you then, nothing in it—empty almost." Mention of the boat hands. I met several to-day who asked about him and whom I greeted for him, as he advised me. One, deaf, oldish, bronzed, strong—W. saying instantly (I did not know his name): "Oh! I know him—know his name, too: he rejoices in the unique and saving name—though the best hand on the river—the unique and saving name of John Smith: he is deaf, but wise, wary. Nature has a keen way of putting its strength out: if a man lack in one sense, nature puts the strength—the strength due that—into another. It is so with Smith." He thought the men on the boat "sensitive to influences"—"water influences," he called them—"as we are not:" "like all men made acute by long training in some special branch of labor." "These fellows—the pilots particularly—are very sensitive anyhow—wonderfully: how often I have gone up into the pilot house—often when they had to help me: sat there—sat there with the Captain. I remember the Brooklyn boats—how sensitive the pilots were to motions I would not have even a suspicion of: I think even their feet were extremely sensitive."

W. often gets back to free-trade. Protection rubs his fur the wrong way. It 's like a perpetual sore with him. To-night he said: "Why am I a free-trader? a free-trader in the large sense? It is for solidarity: free-trade makes for solidarity: the familar, full, significant word: and I hope, oh I hope, there has been no failure to manifest the fact in my books. I know in my own heart that every line I ever wrote—every line—not an exception—was animated by that feeling. I like best of all—better than anything else—in all the thousand pages, the little line or two in the preface to the English edition of Specimen Days: the lines wherein I expressed this feeling, this hope, that the witness of it was 'below any page I had written, anywhere,' &c.: I think I put it this way." He quoted page 94, November Boughs. He had considerable difficulty in getting it out but it came out quite accurately. "I tie myself to that if tying is necessary." W. gave me one of what he calls his "soger boy letters": his draft of such a letter: he even had me read it to him. I don't like to read these letters aloud. They move me too much. I notice that he too is stirred strangely over them hearing them again. But I read. I could not get out of it. It was spread out over ten different slips of paper which were folded in a Sanitary Commission envelope on which he had written: "to Hugo Aug. 7 '63." He said: "Yes it was from the midst of things—to the midst of things: when I went to New York I would write to hospitals: when I was in the hospitals I would write to New York: I could not forget the boys—they were too precious."

Dear Hugo,I received a letter from Bloom yesterday—but before responding to it (which I will do soon) I must write to you my friend. Your good letter of June 27th was duly rec'd.—I have read it many times—indeed Hugo, you know not how much comfort you give, by writing me your letters—posting me up.

Well Hugo, I am still as much as ever, indeed more, in the great military hospitals here. Every day or night I spend four five or six hours among my sick, wounded, prostrate, boys. It is fascinating, sad, and with varied fortune, of course. Some of my boys get well, some die. After I finish this letter (and then dining at a restaurant) I shall give the latter part of the afternoon and some hours of the night to Armory Square Hospital, a large establishment and one I find most calling on my sympathies and ministrations. I am welcomed by the surgeons as by the soldiers—very grateful to me. You must remember that these government hospitals are not filled as with human débris like the old established city hospitals, New York, &c., but mostly with these goodborn American young men appealing to me most profoundly, good stock, often mere boys, full of sweetness and heroism—often they seems very near to me, even as my own children or younger brothers. I make no bones of petting them just as if they were—have long given up formalities and reserves in my treatment of them.

Let me see, Hugo. I will not write anything about the topics of the horrible riots last week, not Gen. Meade nor Vicksborough, nor Charleston—I leave them to the newspapers. Nor will I write you this time so much about hospitals as I did last. Tell Fred his letter was received. I appreciate it, received real pleasure from it—'t was a true friend's letter, characteristic, full of vivacity, offhand, and below all a thorough base of genuine remembrance and good will—was not wanting in the sentimental either (so I take back all about the apostate, do you understand, Freddy, my dear?)—and only write this for you till I reply to that said letter a good long and special measure to yourself.

[This paragraph W. said as I read he did not think was ever sent. He had drawn his pen through it. "It was too damn nonsensical for a letter otherwise so dead serious."] Tell Nat Bloom that if he expects to provoke me into a dignified not mentioning him, nor write anything about him, by his studious course of heartbreaking neglect (which has already reduced me to a skeleton of but little over 200 lbs and a contenance of raging hectic, indicating an early grave). I was determined not to do anything of the sort, but shall speak of him every time, and send him love, just as if he were adorned with faithful troth instead of (as I understand) beautiful whiskers—Does he think that beautiful whiskers can fend off the pangs of remorse? In conclusion I have to say, Nathaniel, you just keep on if you think there 's no hell.

Hugo, I suppose you were at Charles Channing's funeral—tell me all you hear about the particulars of his death—Tell me of course about the boys, what you do, say, anything, everything—

Hugo, write oftener—you express your thoughts perfectly—do you not know how much more agreeable to me is the conversation or writing that does not take hard paved tracks, the usual and sterotyped, but has little peculiarities and even kinks of its own, making its genuineness—its vitality? Dear friend, your letters are precious to me—none I have ever received from anyone are more so.

Ah I see in your letter, Hugo, you speak of my being reformed—no, I am not so frightfully reformed either, only the hot weather here does not admit of drinking heavy drinks, and there is no good lager here—then besides I have no society—I expect to prove to you and all yet that I am no backslider—But here I go nowhere for mere amusement, only occasionally a walk.

And Charles Russell—how I should like to see him—how like to have one of our old times again—Ah Fred, and you dear Hugo, and you repentant one with the dark shining whiskers—must there not be an hour, an evening in the future when we four returning concentrating New York-ward or elsewhere, shall meet, allowing no interloper, and have our drinks and things, and resume the chain and consolidate and achieve a night better and mellower than ever,—we four?

Hugo, I wish you to give my love to all the boys—I received a letter from Ben Knower, very good—I shall answer it soon. Give my love to Ben—If Charles Kingsley is in town same to him—ditto Mullen—ditto Park, (I hope to hear that sweet sweet fiddler one of these days, that strain again)

I wish to have Fred Grey say something for me, giving my love to his mother and father—I bear them both in mind—I count on having good interviews with them when I see New York.

I said to W.: "That 's not so serious as you led me to believe." He smiled: "The undertone is serious: they were grave times: I was not feeling gay and festive in those years: never could get away from the terrible experiences. Emerson asked me: 'Mr. Whitman, how can you stand it? I do not think I could endure it. It would take too much out of me: too much—too much—.'" I asked W.: "Did Emerson always address you as Mister?" "Generally—I may say always. Once or twice he addressed me as Whitman: but he looked a bit uncertain after he had done so as if possibly he might have taken on too much liberty."

W. lay on the bed as I left. The tangerines and a book beside him: he played with them. I was happy. He seemed so well.