Sunday, January 6, 1889.

Sunday, January 6, 1889.

2 P. M. Stopped in on my way to the city. All well there. W. sitting up writing "Critic Jan. 5, '89" on a number of the slips of poem to send off. Gave me one for Clifford, one for myself. On a book near the floor a bulky letter addressed to Kennedy. "I have been writing Sloane: sent a slip along: now am preparing one for Dr. Bucke." Speaking of poem: "I make no pretensions for it: I have not endeavored to pile on the agony: it must go for its own worth, much or little—no doubt little." W. said: "No art for arts sake." Then: "Let nature flow her own way: then leave the rest." Some one had wondered whether W. was "able to write". He laughed: "We might as well ask, can a duck swim?" Read the papers this morning. Handed me back The Stage. "I have gone through it from beginning to end." Also read Press and Record. Had been "thinking over memo for binder" but had "not achieved it yet." Would put out Dave's book so I could get it on my way over to the city to-morrow morning. Where was I going? Still storming: mist, rain: temperature mild. "As the book says, give my love to all inquiring friends." Alluded to a metal plate on the mantel. "It is a card-reciever: someone thought I should have a card-receiver and gave me that: the stamping is Rip Van Winkle—one of the episodes of the story: very good of its kind I suppose: of course I never used it—only put it on the mantel piece—kept it there." Took him back Kennedy's letter and Herald. W. said: "Sylvester did us up proud: we would not have done better ourselves." Was it getting colder? I thought so—very gradually, though mild now. "Anyhow I am prepared: just yesterday I laid in another cord of wood: a man with a cord of wood need not despair—need he?" Then: "I believe these rascally dealers in wood cut us short every time. A cord of wood lasted me nearly all last winter: this winter I have already used over a cord." He forgot that he lived downstairs last winter where he had a coal fire. But he resented my explanation. Insisted that the cords were short. Would give me copy of L. of G. for free library in Clifford's church. Harned has said nothing to me regarding the will—nor has W. I doubt if W. knows H. has it. W. probably thinks it there in the welter still if he thinks of it at all.

Found myself kicking an envelope about the floor: picked it up: marked Attorney General's Office"—date, 1865. W.: "Ah! that is very important. It is some notes on the Harlan matter—long preserved: I came across it again to-day." I said to W.: "They won't seem so important if they get kicked about the floor a few more years." He laughed—then was serious: "That 's sure enough: they should be put in some secure place." Then: "I'll put them away: see that they don't drift onto the floor again." I put in: "There 's only one secure place: you have no secure place here." "What do you mean?" I did not answer. He looked at me inquiringly. "Oh! I see: you mean you are the only secure place." He stopped. I still did not say anything. He spoke up again: "You ain't usually so infernal slow to say what you mean. I suppose you think you need n't say what I already know."

I was looking the documents over. There were four or five envelopes indicating his appointments under the government at Washington. W. said again: "Horace, I 've a mind to adopt you—to take you at your word: it looks to me, too, now, shaky as I am, uncertain as I am about the future, near the wind-up as I am: it looks to me, too, as if maybe it would be best for you to take this stuff and put it where you have put all the rest." "Do you supposed you 'll ever have an use for it?" He was very grave. "No—never: the time is rapidly coming when I'll have no use for anything." I said: "It would be a shame to have anything happen to this old document—your own story of the Harlan business: it would be a shame." W. nodded: "Probably, though you of course attach more importance to it than I do. Still, I can see how more or less valuable it is, going along as it may with the history of those times—with the fortuitous career of Leaves of Grass." Finally he said: "you will find in these envelopes a pretty clear account of my appointments and depointments—of my jobs, one after another, of the salaries attached, of dismissals, and so forth and so forth: most of it all is formally there. I don't know but you had best take it: but you must keep it within reach, so that if anything comes up that demands that stuff in evi- dence—the chance of it is remote—you can trot it out instanter." I was hoping he would say more. He only added: "I wish you would just arrange the documents in the order of their dates and read them to me."

I was in a hurry to get away. But rather than run the chance of putting the thing off to another time and having the precious letters lost again, maybe for good, I sat right down and commenced to read. I had a devil of a time with W.'s Otto story, it was so much interlined. The rest went along smoothly. W. interrupted me some as I proceeded. He said for one thing: "I would not have been mortal if I had not felt some resentment over my discharge at the time: but when a man like Harlan does a thing like that we find generally that he is sincere, often deadly sincere, though a fiercely impossible bigot. Humanistically speaking the Bible and Leaves of Grass are in every way compatible." "But between the Bible as a book used to put chains on people and Leaves of Grass as a book to take them off there is no compatibility whatever," I said. W. shook his forefinger at me: "It seems to me that whenever I start to say a good thing you take it right out of my mouth. It is your very worst habit: it gives my vanity, complacency, many a jar!" Then I said: "Well, do you want me to read or don't you?" "I want you to read, certainly: go ahead: read." So I went through the nine different papers in their order. W. said: "There may be several more papers that belong in that batch: indeed, I think they are: I don't know where they can be now: if, when, they turn up I will see that they are laid aside for you."

I

Department of the Interior, Washington, January 12, 1865. Sir:Upon reporting at this Department and passing a satisfactory examination you will be appointed to a First Class Clerkship at a compensation of twelve hundred dol- lars per annum. I am, Sir, very respectfully, your obt servant

W. T. Otto, Assistant Secretary. Walt Whitman, Esq.Brooklyn, N. Y.

II

Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C., January 24, 1865. Sir:You are hereby appointed to a Clerkship of the first class—in the Office of Indian Affairs, of this Department—the salary of which is $1200 per annum, to commence when you have subscribed the enclosed oath, and entered upon duty. I am, Sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant

W. T. Otto,Assistant Secretary. Walt Whitman, Esq.

of New York.

III

Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C., May 11, 1865.Walt Whitman of New York is hereby promoted to a Clerkship of the Second Class in the Office of Indian Affairs to take effect from and after the first instant.

William T. Otto,Assistant Secretary of the Interior.

IV

Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C., June 30th, 1865.The services of Walter Whitman of New York as a Clerk in the Indian Office will be dispensed with from and after this date.

James Harlan,Secretary of the Interior.

V

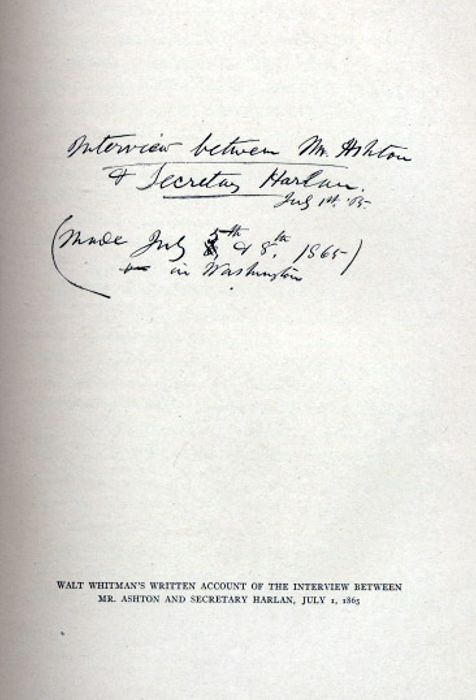

["Interview between Mr. Ashton and Secretary Harlan, July 1st, '65. (Made July 5th and 8th, 1865 in Washington)." That 's the way W. described this paper, which is all written in his own hand].

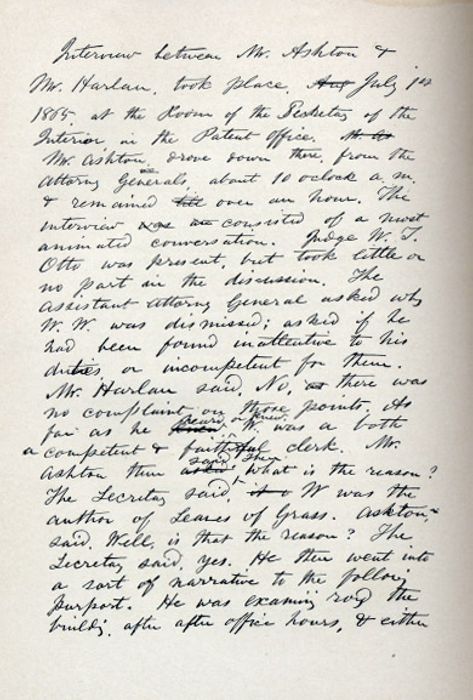

Interview between Mr. Ashton and Mr. Harlan took place, July 1st, 1865, at the Room of the Secretary of the Interior in the Patent Office. Mr. Ashton drove down there from the Attorney General's, about 10 o'clock A. M. and remained over an hour. The interview consisted of a most animated conversation. Judge W. T. Otto was present, but took little or no part in the discussion. The Assistant Attorney General asked why W. W. was dismissed; asked if he had been found inattentive to his duties, or incompetent for them. Mr. Harlan said, No, there was no complaint on those points. As far as he heard or knew, W. was a both competent and faithful clerk. Mr. Ashton then said, Then what is the reason? The Secretary said, W. was the author of Leaves of Grass. Ashton said, Well, is that the reason? The Secretary said, Yes. He then went into a sort of narrative to the following purport. He was examining round the building, after office hours, and either in or on a desk he saw the Book. He took it up, and found it so odd, that he carried it to his room and examined it. He found certain passages marked; and there were marks by and upon passages all through the book. He found in the book in some of these marked passages matter so outrageous that he had determined to discharge the author, &c. &c. &c.

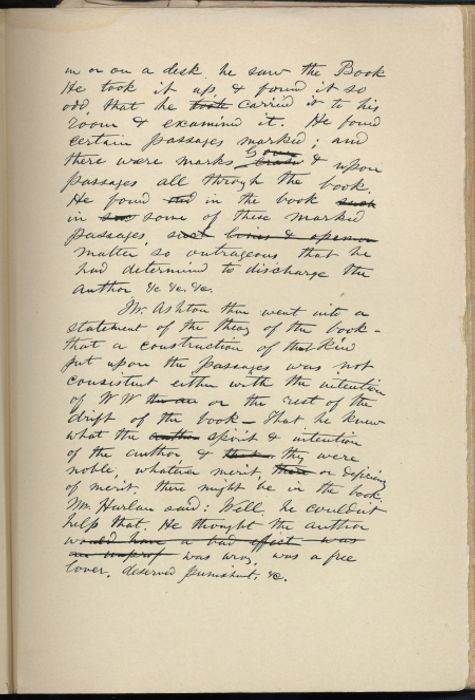

Mr. Ashton then went into a statement of the theory of the book—that a construction of that kind put upon the passages was not consistent either with the intention of W. W. or the rest of the drift of the book—That he knew what the spirit and intention of the author, and they were noble, whatever merit, or deficiency of merit, there might be in the book. Mr. Harlan said: Well, he could n't help

WALT WHITMAN'S WRITTEN ACCOUNT OF THE INTERVIEW BETWEEN

WALT WHITMAN'S WRITTEN ACCOUNT OF THE INTERVIEW BETWEEN

MR. ASHTON AND SECRETARY HARLAN, JULY 1, 1865

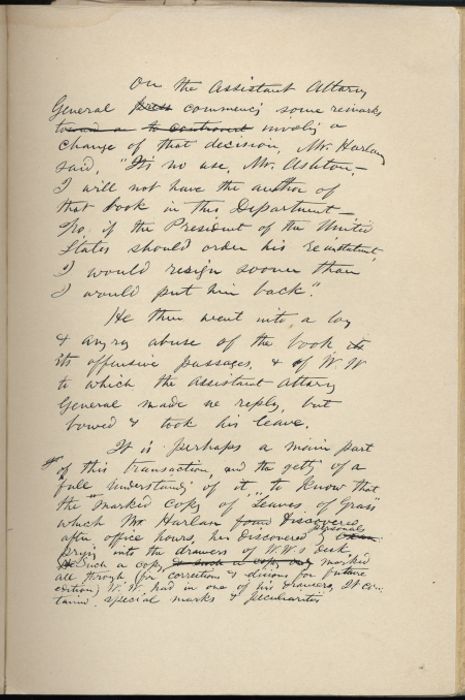

Facsimile of manuscript notes by Whitman, 1 July 1865, page 1

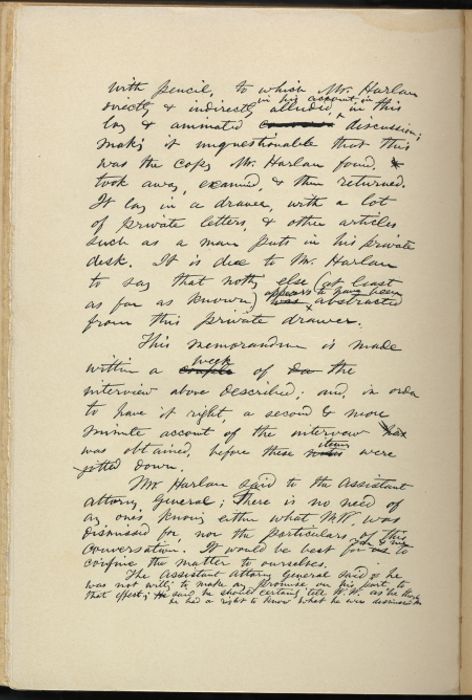

Facsimile of manuscript notes by Whitman, 1 July 1865, page 2

Facsimile of manuscript notes by Whitman, 1 July 1865, page 2

Facsimile of manuscript notes by Whitman, 1 July 1865, page 3

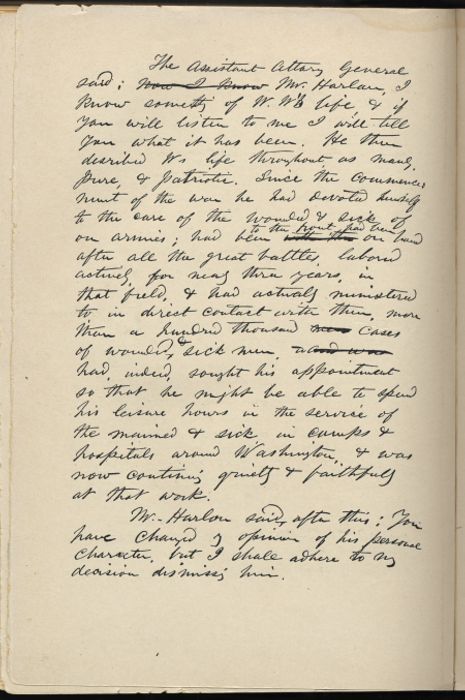

Facsimile of manuscript notes by Whitman, 1 July 1865, page 3

Facsimile of manuscript notes by Whitman, 1 July 1865, page 4

Facsimile of manuscript notes by Whitman, 1 July 1865, page 4

Facsimile of manuscript notes by Whitman, 1 July 1865, page 5

Facsimile of manuscript notes by Whitman, 1 July 1865, page 5

Facsimile of manuscript notes by Whitman, 1 July 1865, page 6

that. He thought the author was wrong, was a free lover, deserved punishment, &c.

Facsimile of manuscript notes by Whitman, 1 July 1865, page 6

that. He thought the author was wrong, was a free lover, deserved punishment, &c.

The Assistant Attorney General said: Mr. Harlan, I know something of W. W.'s life, and if you will listen to me I will tell you what it has been. He then described W.'s life throughout as manly, pure, and patriotic. Since the commencement of the War he had devoted himself to the care of the wounded and sick of our armies; had been to the front, had been on hand after all the great battles, labored actively, for nearly three years, in that field, and had actually ministered to, in direct contact with them, more than a hundred thousand cases of wounded and sick men, had, indeed, sought his appointment so that he might be able to spend his leisure hours in the service of the maimed and sick, in camps and hospitals around Washington, and was now continuing quietly and faithfully at that work.

Mr. Harlan said after this: You have changed my opinion of his personal character, but I shall adhere to my decision dismissing him.

On the Assistant Attorney General commencing some remarks involving a change of that decision, Mr. Harlan said, "It 's no use, Mr. Ashton—I will not have the author of that book in this Department. No, if the President of the United States should order his reinstatement, I would resign sooner than I would put him back."

He then went into a long and angry abuse of the book, its offensive passages, and of W. W., to which the Assistant Attorney General made no reply, but bowed and took his leave.

It is perhaps a main point of this transaction, and the getting of a full understanding of it, to know that the marked copy of Leaves of Grass which Mr. Harlan discovered after office hours he discovered by personally prying into the drawers of W. W.'s desk. Such a copy, marked all through (for corrections and elisions for future edition) W. W. had in one of his drawers. It contained special marks and pe- culiarities with pencil, to which Mr. Harlan directly and indirectly alluded in his account in this long and animated discussion; making it unquestionable that this was the copy Mr. Harlan found, took away, examined, and then returned. It lay in a drawer, with a lot of private letters and other articles such as a man puts in his private desk. It is due to Mr. Harlan to say that nothing else (at least as far as known) appears to have been abstracted from his private drawer.

This memorandum is made within a week of the interview above described; and, in order to have it right, a second and more minute account of the interview was obtained, before these items were jotted down.

Mr. Harlan said to the Assistant Attorney General: There is no need of any one's knowing either what W. W. was dismissed for, nor the particulars of this conversation. It would be best for you and me to confine the matter to ourselves.

The Assistant Attorney General said he was not willing to make any promise, on his part, to that effect; he said he should certainly tell W. W. as he thought he had a right to know what he was dismissed for.

VI

["Sept. 29, '65. Int. with Judge Otto—he saw the blue-covered book on Mr. Harlan's desk." This in W.'s handwriting and the paper that follows.]

The Acting Secretary of the Interior, Wm. T. Otto, on his way to cabinet meeting, called at the Attorney General's office on business and stopt at my desk a moment. He said to W. W., "I hope you are well situated here-I was sorry to lose your services in our Department, for I considered them valuable. The affair" (my dismissal) "was settled upon before I knew it."

In the course of the conversation then and there the ques- tion was asked Mr. Otto of the particular copy of Leaves of Grass which Mr. Harlan had in his room as alluded to in his conversation with the Assistant Attorney General and whether it was a volume bound in blue paper covers—and anything like this—pointing to a volume of Laws, paper bound, octavo, about the same thickness. He said he had had no special conference with Mr. Harlan on the volume. A 500 page paper vol. lying on the table was shown him, and he was asked if it was such a vol. He said that he had seen on Mr. Harlan's desk a volume of Leaves of Grass, in blue paper covers, and the pages of the poems marked more or less all through the work; he remembers this volume being shown him and opened by some one who saw on his, Mr. Otto's, table a copy of Drum Taps.

VII

(All in W.'s handwriting except B.'s signature)

Attorney General's Office, Washington, Aug. 31, 1867. Hon. Mr. Binckley,Acting Attorney General.

Sir:The undersigned respectfully asks leave of absence from the 9th of September to the 12th of October.

Walt Whitman.Leave granted, as above.

John M. Binckley,

Acting Attorney General.

VIII

Department of Justice, Washington, Mar 10, 1873. Walt Whitman, Esq.,Washington, D. C.

Sir: You are hereby transferred from the office of the Attorney General to a clerkship of the third class in the office of Solicitor of the Treasury, to take effect on the 1st instant.

Very respectfully George W. Williams,Attorney General.

IX

Department of Justice, Washington, June 30, 1874. Walt Whitman, Esq.,Camden, N. J.

Sir: Congress at its last session abolished one of the third class clerkships in the office of the Solicitor of the Treasury and upon my requesting the Solicitor to designate which of the three he could best dispense with, you were named. It is, therefore, my duty to inform you that your service will not be required from and after the first proximo.

I regret to have to send you this notice, but under the law limiting the force in the office the proposed reduction is necessary, and I do not feel at liberty to overrule the wishes of the Solicitor of the Treasury.

Very respectfully, George W. Williams,Attorney General.

I asked W.: "Are they all the documents in the matter?" He said: "Yes: practically all: there may be an item or so which I have not tied together here. If they turn up I' ll see that they are given to you for preservation. One thing, Horace, about that Harlan matter: it 's history now: you don't need my story: another thing, Horace: don't ever assail Harlan as if he was a scoundrel: he wasn't: he was only a fool: there was only a dim light in his noodle: he had to steer by that light: what else could he do? Then, Horace, remember this too—that he was afterwards sorry for it: I have been told so by newspaper men: they knew him: out in the west—in his own country: he told them he thought it was a mistake: he was a bigot—that was all: yet he had the courage of his convictions: he did n't allow Ashton's eloquence to shake him: he threw me out: his heart said, throw Walt Whitman out: so out I went: I have always had a latent sneaking admiration for his cowardly despicable act"—he laughed: "After all, the meanest feature of it all was not his dismissal of me but his rooting in my desk in the dead of the night looking for evidence against me. What instinct ever drove him to my desk? He must have had some intimation from some one that I was what I was." As I left W. said: "We 'll talk of this again: be sure you put the documents in your safest place!"

This was one of the unusual occasions upon which I could see W. W. by daylight. Looked rosier than for some time: hand firmer, more vigorous: eye clearer. I did not stay after I had read the letters: was on my way to Philadelphia.