Wednesday, January 9, 1889.

Wednesday, January 9, 1889.

7.55 P. M. W. sitting reading book catalogue. Had been well: "up all day": reading, writing, "some," making himself "as comfortable as possible." Visitors few: yesterday one or two: not more to-day". Is practically let alone mornings. No sign of any particular ailment, Ed says. "He 's punishing an awful amount of wine nowadays." Takes milk, cold water, hot water. I have known him twice or three times of an evening while I was there scoop hot water from the bowl on the stove and drink it. As to wine, what Ed calls much is not much after all. But as Dr. Bucke discourages its use altogether it may not be best for W. to be so stubborn. "Tom was in," he said: "brought me a nice bottle of wine: asked me if I did not want to read Robert Elsmere: he has a copy which no one is using now. I told him to bring it along—I would try to read it." I said I had no idea the book would interest him: it took up problems in a way he had never cared for: it was rather for the class whose spokesman it was—the great mass just at the orthodox loosening point. "You think," he said, "that there is that great mass movement?" Then: "I can easily see that what you say is true: for my part these things have little value: but I shall try the book: if it will paddle its own canoe, well and good: if it will not, let it go the way of the others: I won't force it through."

That had been the trouble with Tolstoy's Confession, now for days lain untouched. "I gave it up," he explained: "I got about a third of the way through: it was too much for me: I find little pleasure in it: it 's poor reading for me: I was never there. Tolstoy's questionings: how shall we save men? sin, worry, self-examination—all that: I have never had them. I never, never was troubled to know whether I would be saved or lost: what was that to me? Especially now do I need other fodder: my mind is in such a state I need food which will frivol it. I know a bright girl: she expressed this for me: she would sometimes say: 'We went out for a drive, came home, had our supper, then frivolled the evening away.' I want to frivol my evening away." He was very earnest. "I find better employment, enjoyment—both—in reading one of Scott's novels." Of course he "did not mean to say Tolstoy has no place or significance." He was conscious that, "there are things, persons, making it possible to argue for, prove, Tolstoy." Only, "that conclusion" was not his conclusion. "But with all this I am glad I read the book: it shows me more clearly what Tolstoy stands for: besides, the last third or half of the book probably justifies the first. Taking it up at another time this might be enforced even upon me: it looks as if the

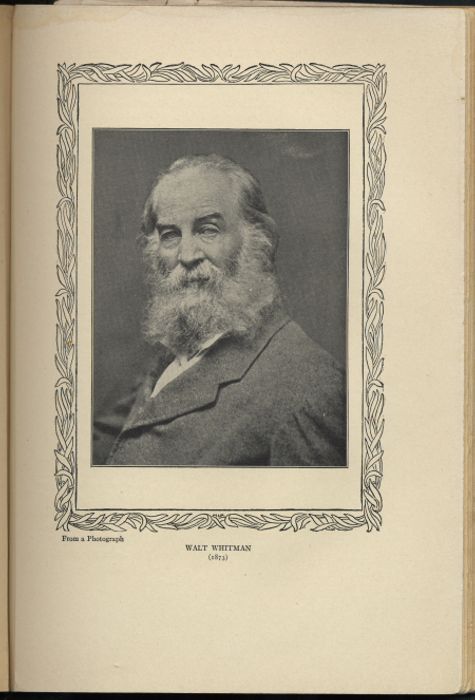

From a Photograph

From a Photograph

WALT WHITMAN

(1873)

Reproduction of a photograph of Whitman, 1873

first part, the part I read, was introduced in order that the second might be written. There are undeniable and undoubted marks of the great man in all that Tolstoy writes, but the introspective, sin-seeking nature makes no appeal to my constitutional peculiarities. In this respect Tolstoy may better represent the present day than I do."

As to the Carlyle letters: "I still hold on there." It was "good" for him "to know them: to know even those which had no great interest. They throw out glints, lights—even shadows—of his early life which it is important not to miss." This book did not depress him. "It is on the whole brighter than the other Carlyle books." He asked me: "What did you do at the Club last night? Whom did you meet?" Then as to The Evolution of Ethics: "It opens a vast field: you should have had the Doctor there: that is his subject—his favorite theme: he is booked—has thought: has his own ideas." I gave him details as far as I could, especially speaking of a gem of a speech by Brinton in which W. took the greatest interest. W. said he was "interested enough in the subject but not in it as a subject for debate." He produced an old envelope addressed to him (his sister's handwriting: Burlington, Vermont) in which he had crowded some bulky sheet. Handed it to me. "This is Note at End." "I have not found the German paper Knortz sent me: when I do find it you shall have it: you can read it and pass it on to Dr. Bucke: there was about so much in it about me"—measuring about two inches—one forefinger with the other: "but I can't read a word of it: I know nothing at all about the German."

I supposed he had sent Bucke Boston Herald early in the week, but he has not done so even yet. "You sent for some? We will send one to Doctor when they come." Letter from Bucke. "It contained nothing new." Saw McKay: talked over cover. Will see him at Oldach's to-morrow. There will be no copies sent out for reviews. McKay suggested that some means be taken to get the book into England. Suggested also that the books should be numbered. W. said: "I am satisfied to have you proceed: so far as I am concerned I am content to rest with the books as they are: I have a batch of them here now, right in the room: in the boxes, about the wall: I confess I view them with a sense of comfort: am proud of them just as they come up in the cheap fifteen cent back." Still he recognized the market arguments. "I am willing to have a rich showy cover shown me: am willing to accept it: not showy in the vulgar sense but showy for what it is." He had been "curious to know what the great binders, the really great workmen, would do with the book." "I suppose if Paris was across the street we could get one of the artistic fellows there to lend a hand: but of course it is useless to think of that: it is impossible, not to be thought of, in this country."

Dave said W. should be careful in giving copies away. W. said: "I do not need to be reminded to be stingy: I am aware of the necessary caution: I shall not scatter them. I gave away a great many copies of November Boughs: there were many very dear friends, friends I valued, valued highly—particularly girls, women, mothers: they had done me service: I could not give them money: therefore I used the little book: it showed where I stood: was always rightly accepted in that same spirit." Several times afterwards W. referred again to "the Swiss," as he calls Oldach's binder: "Be sure you consult with him: he must not be left out." Is not "anxious about the book," but "now we have started let us forge ahead." Moulton asks McKay for a W. W. cut. W. said: "I begin to think Moulton is a fraud: I am almost sorry we had anything to do with him." There was "that Drum Taps fellow," too, "probably a fraud." "I am not to be taken in: I am too old a bird at that: I have experienced all sizes and styles of the autograph monster."

W. is so well now Ed has little or nothing to do. The other day E. complained. W. said: "Well—I'll haul him up some work." At once wrote the wine message to Harned and sent Ed to bank with some checks. Some one had sent W. Ingersoll's The Gods in a pamphlet. W. was happy over it. "I wonder if anybody ever hit back at the orthodox God better than our dear Bob? Ever spit upon it with such necessary and effective derision? I read this superb thing to-day: it seems just perfect. Of course Bob does not go far enough: he gets rid of the old thing—does it without a quaver—ends it forever. But God? God? Well, there are other divinities: they are not of the hell and damnation sort: they are not of the legs and arms sort—the personal sort: they yet remain, more firmly on their thrones, in the race, than ever: they continue their supremacy. Bob does not intellectually account for them: he has them in his heart: they are one part of his noble protest—whether he knows it or not. I sometimes ask: Why does Bob not see more? Then I say: If he saw more maybe he could not do his work? I ask myself that question over and over again. He lives more: the chief matter is living. The main thing is that he has done in his divinely appointed job: O the dear wonderful man! He was sent by high heaven to save the race and he has done it. We talk about salvation: we need most of all to be saved from ourselves: our own hells, hates, jealousies, thieveries: we need most to be saved from our own priests—the priests of the churches, the priests of the arts: we need that salvation the worst way. The Colonel has been the master craftsman in this reconstruction: he has taken us by the ears and shaken the nonsense out of us: the criminal institutions we have built up on our already overburdened backs. As I read this old piece over again my first impression of the sanity, the health, the virile humanity, of it all was renewed in me. Some things—some systems—requiring to be removed, can't be got rid of with a too kind law: they have to be rejected scornfully—with a species of almost ghoulish delight. Hell is such a system: the revengeful gods—they are such a system: the sould be summarily ejected: they should be stamped out without equivocation." I said: "You spoke of the priests of religion and the priests of the arts. We still have the priests of commerce to contend with." "So we have: doubly so: the priests of commerce augmented by the priests of churches, who are everywhere the parasites, the apologists, of systems as they exist."

W. said to-night: "That whelp, Charlie Heyde, always keeps me worried about my sister Hannah: he is a skunk—a bug"—I laughingly broke in: "What have you got against bugs and skunks Walt?" He nodded, amused. "That 's so: what have I?" Then: "Did I never tell you about this man Heyde? He has led my sister hell 's own life: he has done nothing for her—never: has not only not supported her but is the main cause of her nervous breakdowns. He is a leech: is always getting at us: himself gets most of the money my sister has from us—squanders it on himself: still leaves her sick, poor, uncared for. Did I never tell you about him? O yes! I must have done so. I am always obliged to reach my sister indirectly—through her doctors up there at Burlington, or perhaps a friend or two. Charlie is always in the way: he is the bed-buggiest man on the earth: he is almost the only man alive who can make me mad: a mere thought of him, an allusion, the least word, riles me. Oh! that makes me think of the gentle Emerson! He said one day: 'Mr. Whitman, your love is very comprehensive—includes about everybody: but don't you sometimes find there are people who insensibly try your philosophy and nearly break it down? Perhaps not exciting you to hate but surely stirring up in you an unlovely repugnance and resentment?' I said to him: 'I see you have met such people.' He did n't take long to say: 'Yes I have. And you?' It made me laugh, especially as coming from him. 'I 'm afraid I have, too,' I said. Then he put his hand on my arm and said: 'It comforts me to have you say that: it provides me with a companion in my delinquency!'" W. stopped. I waited. Then: "How like the sweet Emerson that was! Delicious! Delicious!" I put in: "So you have a place for Charlie?" "Yes: a hot place!" Further: "Henry Clapp said to me: 'Walt you include everything. What have you got to say to the bed bug?' I wonder if Henry could have been thinking of Charlie Heyde?" All this was by the way.

W. gave me a pencil draft of a letter of inquiry he had written to Dr. Thayer twenty years before. I asked W.: "Has she always had this trouble?" "Yes—from the first—ever since she married the whelp." "Why, Walt, this letter is twenty years old." "I know it: and her trouble is twenty years older." "Is the situation up there the same now as it was when you wrote this letter?" "The same or worse if worse is possible." Then I asked him: "Are you quite sure you want me to have this letter?" He nodded: "Yes: you see how it is: I want you to be in possession of data which will equip you after I am gone for making statements, that sort of thing, when necessary. I can't sit down offhand and dictate the story to you but I can talk with you and give you the documentary evidence here and there, adding a little every day, so as finally to graduate you for your job!" He was both grave and quietly jocular about all this. I then read him the letter. He almost invariably has me do this now with letters he gives me.

December 8, 1868. Dr. Thayer,Dear Sir: Won't you do me the very great favor to write me a few lines regarding the condition of my sister, Mrs. H. L. Heyde. I am sure, from what I hear, that it is mainly to your medical skill, and your kindness as a good man, that she got through her late illness. She seems by her letters to be left in an extremely nervous state. Doctor, please write me as fully as you think proper. Though we have never met personally, I have heard of you from my mother and sister. I must ask you to keep this letter, and the whole matter, strictly confidential, and mention it to no person. My sister in a late letter wished me to write you and thank you for your great kindness to her.

W. said: "My mother was very gentle, though strong: you have seen her, talked with her: she had sad days over this thing, which almost amounted to a tragedy. George would get indignant: used to want to go to Hannah—raise hell—handle Charlie without gloves: but my mother restrained us—thought it would do no good. You can't very well break in on domestic situations and straighten them out: they generally have to be scrupulously avoided: the third person as a rule finds himself helpless." I said: "Charlie is still a thorn in your flesh?" "Yes, and will be till one of us is dead: he is a cringing, crawling snake: uses my sister's miseries as a means by which to burrow money our of her relations." I said: "Walt, I never heard you go on so about anyone before." "I never felt so about anyone before. I think if Charlie was a plain everyday scamp I'd not feel sore on him: but in the role of serpent, whelp, he excited my active antagonism."