Wednesday, November 5, 1890

Wednesday, November 5, 1890

8:20 P.M. With W. nearly an hour, in such active talk as we have not had together for many a day. His condition evidently vigorous and happy.

Talked of elections. He was "happy in it all: for the slap at Quayism in Pennsylvania, for the general onslaught on the McKinley bill." Thought "things looked about to right themselves." He had voted for Harned, "but Tom has not been here for some days." It was "sign of good for America" that turns of this sort could occur. "And even the farmers in the West seem aroused." What about? And as I detailed some points in the Farmer's Alliance, he thought, "It is significant—and a wheel within a wheel?"

Had sent Kennedy the New Ideal today. "He liked the Ingersoll lecture, of course: from the Times bit I sent him, made up a quarter-column piece for Sunday's Transcript. We must send him a Truth Seeker as soon as circumstances will allow."

Gave me letter from Bucke. Also showed me an old envelope worded "Horace" containing a slip (as he said, "for your piece").

I then showed him something from S. P. Putnam, "The Eloquence of Ingersoll," which he read and called "fine," adding, "He deserves it, too: it is not a word too much or out of place." Asked me about Putnam: "I had an impression that he was, or is, an expert stenographer, that he held some eminence in that work." He then asked me somewhat about him. Law had sent me this piece from Putnam. W. said of Law: "I liked the fellow the times he was here; his atmosphere attracts me." Law had sent also the New York World matter of 26th about W. and Ingersoll. Left copy with W. He had "particular desire to see if it was parent to the Press piece," as undoubtedly it was. Commented on writer's evident pressure to prove W. in a dangerous condition of senility, etc., and W. said, "I can see that intention myself. But how could he know?" The writer's confusions were manifold—this evidently the inspiration of the Press article. No one about here knows who did it, but I suspect it was the young fellow I had the fight with at the entrance to dining room that night. W. said, "I have had the reputation of being grizzled past belief. So I am judged accordingly." Then W. said, "We will send our papers abroad liberally." I hinted, "I have just written Baker to that effect."

"Good! To Symonds and many others." I had also written Baker definitely assenting to the proposition to write for the Arena. W. promised, "I will give you an idea of a subject within a very few days." Then, "If I go into the North American Review, then into Lippincott's next month, then again into the North American Review, then in the Arena, the world will think I am lively enough for something. Kennedy must have seen this World piece, for he wrote me the other day, about 'Old Poets,' that it was a pretty lively word from a dead man." How would it do for me to write Gilder and question why W. appeared tabooed in Century dictionary? W. demurred, "I don't think it well to follow the idea out. Even at Doctor's instance, for the world knows how intimate we are and

would think I had inspired you. Besides, they are not to blame. They cannot help it. They go as far as they see, then stop. To some of these people, I am what Bob Ingersoll is to others: we are feared, inspire horror, and I am not surprised: we could not be for such people. Just the last few days I have received a couple of letters—characteristic letters—bearing upon these things. One of them roundly abuses me, calls me 'accursed,' is evidently written by a woman who for some reason or other thinks my existence a threat. And the other is a man's—seems to have come from something offensive I said in the 'Old Poets' piece. What could it have been?"

"The Whittier reference?"

"No, hardly that. I think that what I said of Whittier could almost have been endorsed by a Whittierite. It was simple, direct. If anything, my Longfellow paragraph; and yet I did not suspect I had anywhere said anything ill-natured, narrow, indicating either jealousy or knowing injustice." Nor had he. I mentioned his naming Lanier as felicitous, as Lanier had always so ingraciously estimated W., and he said, "I am glad you like that: it was meant just as it stands." I told him of my saying to narrow alignments: "However you have a platform that shuts me off, my platform includes you," and I illustrated, "'Leaves of Grass' is such a big platform, or nothing." W. assenting, "I hope so! and that is so good, so good!" He developed the magazine question: "I have a piece in the coming Lippincott's, 'To the Sunset Breeze.' Stoddart wrote me about it some time ago, sending proof, which I returned at once, nothing at all being the matter with it. Stoddart said to me that Scovel told him I had spoken of him, Stoddart, as worldly, or wordly. And he asked, 'What do you mean by that?' His letter was in a pleasant enough vein, rather towards the humorous. I do not remember that I ever said such a thing to Jim: it is nearly certain I did not. Stoddart told me he would come over in a few days to consult with me about the arrangement of the poems, but he has not yet been here. I think he is a free, good, democratic fellow, beyond airs and snobbiness. He would receive you well if you

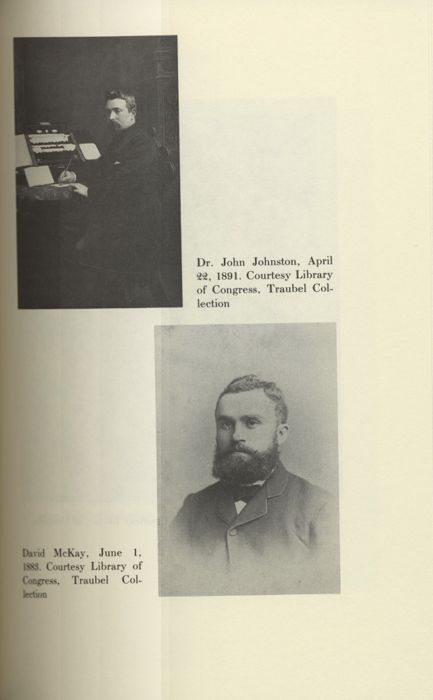

Dr. John Johnston, April 22, 1891. Courtesy Library of Congress, Traubel Collection

Dr. John Johnston, April 22, 1891. Courtesy Library of Congress, Traubel Collection

David McKay, June 1, 1883. Courtesy Library of Congress, Traubel Collection

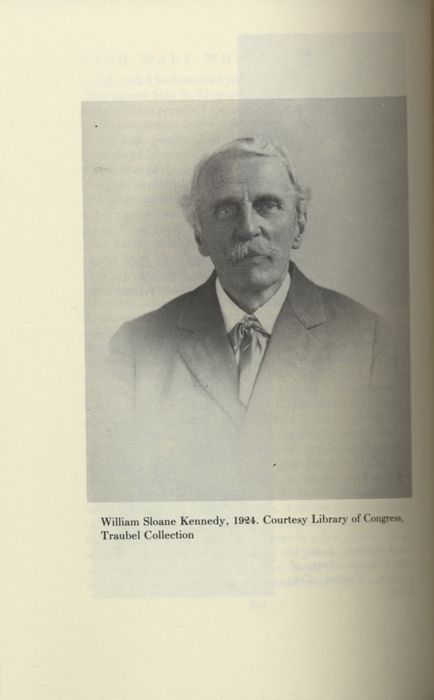

William Sloane Kennedy, 1924. Courtesy Library of Congress, Traubel Collection

William Sloane Kennedy, 1924. Courtesy Library of Congress, Traubel Collection

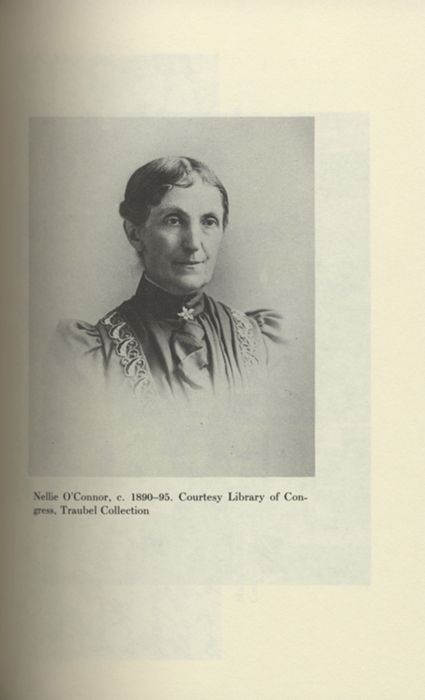

Nellie O'Connor, c. 1890-95. Courtesy Library of Congress, Traubel Collection

Nellie O'Connor, c. 1890-95. Courtesy Library of Congress, Traubel Collection

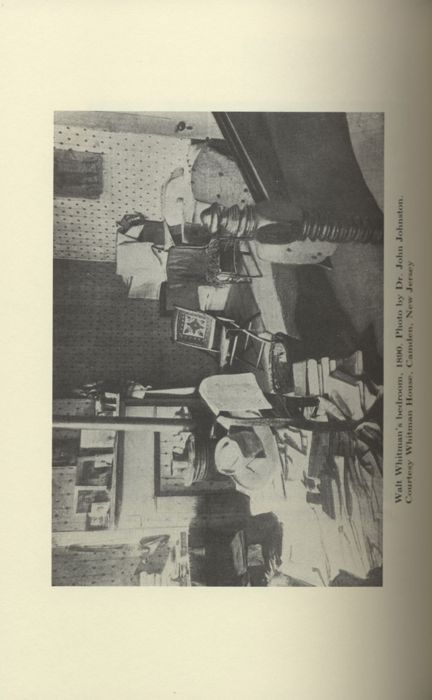

Walt Whitman's bedroom, 1890. Photo by Dr. John Johnston. Courtesy Whitman House, Camden, New Jersey

Walt Whitman's bedroom, 1890. Photo by Dr. John Johnston. Courtesy Whitman House, Camden, New Jersey

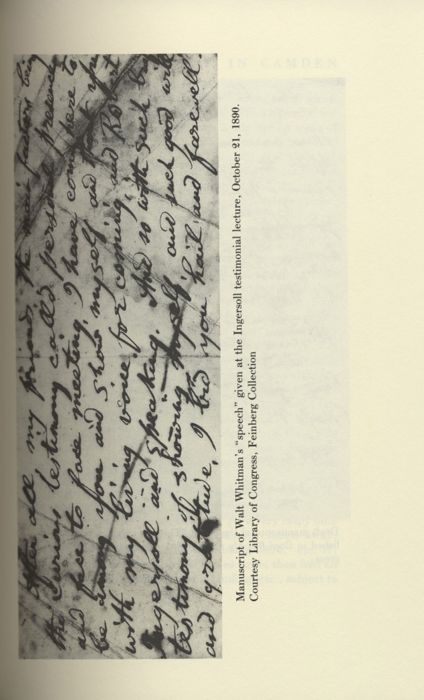

Manuscript of Walt Whitman's "speech" given at the Ingersoll testimonial lecture, October 21, 1890. Courtesy Library of Congress, Feinberg Collection

Manuscript of Walt Whitman's "speech" given at the Ingersoll testimonial lecture, October 21, 1890. Courtesy Library of Congress, Feinberg Collection

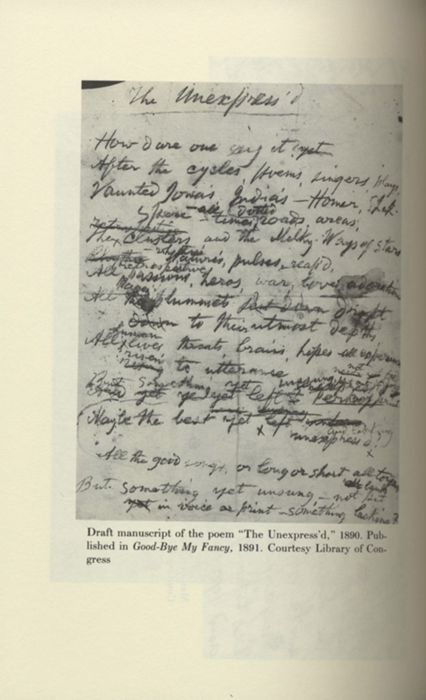

Draft manuscript of the poem "The Unexpress'd," 1890. Published in Good-Bye My Fancy, 1891. Courtesy Library of Congress

went there. My first idea was to have the poems together, making a page, but he wished to use them each by itself, which I can see to be the true business issue of it." Then he called my attention to the fact that "Scovel is evidently urging some of his (Scovel's) Whitman matters upon Stoddart, and Stoddart, though not perhaps smitten of Jim, is a good deal with him perhaps—certainly drinks with him. But it is not pleasant to me to think of Scovel writing anything at all about Walt Whitman." And so he pressed me that I write to Stoddart, volunteer a piece, to head Scovel off. "You could do it best of all. Jim is an unpleasant fact. You would not need to write severely to Stoddart. I am quite willing you should use my name—should say that I desire it—that I object to having Scovel proceed further about me. Do it all kindly; I know you can. I have a peculiar liking for the women of Jim's family—appreciate what they have done for me, and would not like it to seem that I am ungrateful or treacherous. Of course I know that whatever you write to Stoddart will get to Jim sooner or later, but if written mildly it will do no harm. It is an embarrassment, however, that must be met. And there is no reason either for mentioning the New England piece. Let your word be spontaneous—either to say or not, as the mood urges. It is a great thing to let life play to such measure—spontaneity." He pressed me to present this matter to Stoddart immediately.

Draft manuscript of the poem "The Unexpress'd," 1890. Published in Good-Bye My Fancy, 1891. Courtesy Library of Congress

went there. My first idea was to have the poems together, making a page, but he wished to use them each by itself, which I can see to be the true business issue of it." Then he called my attention to the fact that "Scovel is evidently urging some of his (Scovel's) Whitman matters upon Stoddart, and Stoddart, though not perhaps smitten of Jim, is a good deal with him perhaps—certainly drinks with him. But it is not pleasant to me to think of Scovel writing anything at all about Walt Whitman." And so he pressed me that I write to Stoddart, volunteer a piece, to head Scovel off. "You could do it best of all. Jim is an unpleasant fact. You would not need to write severely to Stoddart. I am quite willing you should use my name—should say that I desire it—that I object to having Scovel proceed further about me. Do it all kindly; I know you can. I have a peculiar liking for the women of Jim's family—appreciate what they have done for me, and would not like it to seem that I am ungrateful or treacherous. Of course I know that whatever you write to Stoddart will get to Jim sooner or later, but if written mildly it will do no harm. It is an embarrassment, however, that must be met. And there is no reason either for mentioning the New England piece. Let your word be spontaneous—either to say or not, as the mood urges. It is a great thing to let life play to such measure—spontaneity." He pressed me to present this matter to Stoddart immediately.

W. thought that though Kennedy's judgment on the Critic might seem severe, it was "sound" for "the paper has gone down in the vortex—that dreadful press and pull of New York professional literary life."

Said he had not heard from Burroughs since his trip to Camden.

W. explained that while I was away he "got a very raspy note from Oldach practically asking that I take my sheets away, saying there was nothing to him in their being there," etc. W. now would have Oldach bind up 150 copies more, then fold all rest of the sheets and arrange them for binding, etc., subject to order. Gave me memorandum letter to that effect. Said, "And tensions multiply: I have also had word from Dave, not in kindest measure. When I sent him the first 50 copy order of the big book, I told him I would give them to him for three dollars per copy spot cash. And as with this, so with the second order of 50. A while ago (I think while you were away) he sent over for a copy, which I forwarded at once, reminding him in a note of what he owed me. And this seems to have provoked him, for he wrote back to the effect that there was nothing in the books to him—that if he had known what I now told him he would not have handled them—that he had thought to wait till his own 90 day collections were made, etc. Which of course surprised me, both as to tone and understanding—for I had been explicit enough. But never mind. I know Dave is straight. But so far these big books have not given me back my money. Will not do so till I make this big collection from Dave for the foreign copies. I remember that Doctor urged me at the time we produced the books to make the price ten dollars, and sometimes I regret I did not. Doctor believed the world would come around to us—might resist for a while but was bound to yield in the end."