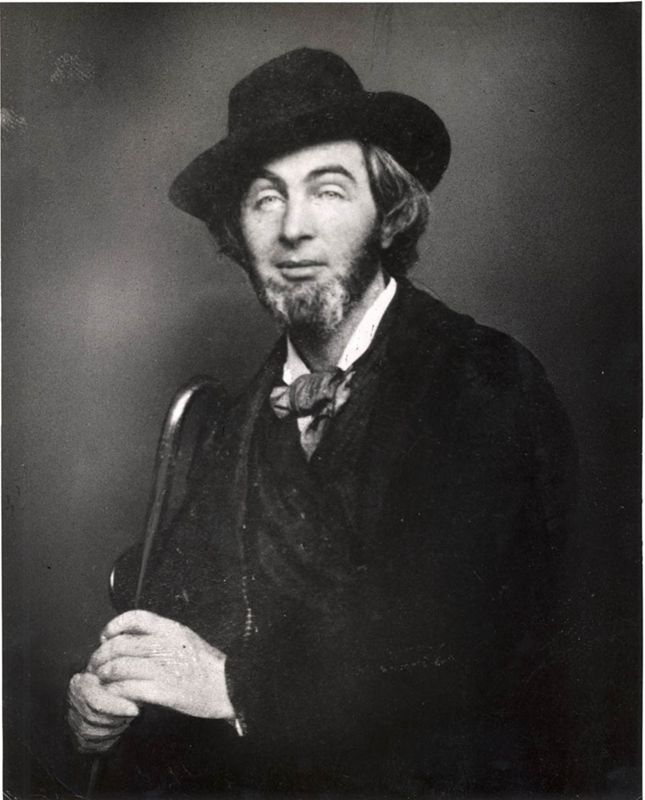

Walt Whitman by John Plumbe Jr.?, ca. 1848–1854

This image derives from a lost daguerreotype. Without the original, dating is difficult, but judging by Whitman’s appearance—his beard grayer than in the New Orleans portrait—this portrait probably derives from the period between 1849 and the early 1850s. This shadowy time in Whitman’s biography is sometimes referred to as his “Travelling Bachelor” era—after a series of short essays, “Letters from a Travelling Bachelor,” that he wrote for the New York Sunday Dispatch between 1849 and 1850 under the pen name “Paumanok.” The first essay of the series concludes with Whitman extolling the virtues of beards, writing that a “full-whiskered grizzled old chap” who worked on a fishing boat had informed him that “an application, while out there, of the razor or shears was equal to aches,” and the only defense against cold and illness “was to let their beards and hair grow.”

But much more than Whitman’s hairstyle was changing in 1850. In the spring of that year, he vented his anger at Daniel Webster, a longtime abolitionist who had come out in support of fugitive slave laws in March. For reasons we can only guess, however, Whitman unleashed not a scathing editorial, but a blunt, free-verse poem that likened Webster to Judas. Entitled “Blood-Money,” the poem appeared in the New York Tribune on March 22. On June 14, he published a similar poem in the Tribune, entitled “The House of Friends,” in which he urged: “Virginia, mother of greatness, / Blush not for being also the mother of slaves / You might have borne deeper slaves— / Doughfaces,” a derisive term for Northerners who were “like dough” in the hands of Southern slaveholders. And a week later, he published a third poem in the Tribune, entitled “Resurgemus.” Though equally critical, the poem ended on a note of optimism:

Liberty, let others despair of thee,

But I will never despair of thee:

Is the house shut? Is the master away?

Nevertheless, be ready, be not weary of watching,

He will surely return; his messengers come anon.

These were the first lines ever published of what would later become Leaves of Grass, and they were the last that anyone would read by Whitman until he dramatically reemerged in 1855 as “an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos.”

Walt Whitman described himself in an 1842 New York Aurora article: "we took our cane, (a heavy, dark, beautifully polished, hook ended one,) and our hat, (a plain, neat fashionable one, from Banta's, 130 Chatham street, which we got gratis, on the strength of giving him this puff,) and sauntered forth to have a stroll down Broadway to the Battery . . . on we went, swinging our stick, (the before mentioned dark and polished one,) in our right hand—and with our left hand tastily thrust in its appropriate pocket, in our frock coat, (a gray one)."

An anonymous writer for Appleton's in 1876 remembered Whitman during this time as "a pleasant gentleman, of agreeable address, [who] went into society as well attired as his precarious resources would allow." William Cauldwell, who worked as a printer on the Aurora in the early 1840s and who knew Whitman well, recalled in 1901 what the poet looked like then: "Mr. Whitman was at that time, I should think, about 25 years of age, tall and graceful in appearance, neat in attire, and possessed a very pleasing and impressive eye and a cheerful, happy-looking countenance. He usually wore a frock coat and high hat, carried a small cane, and the lapel of his coat was almost invariably ornamented with a boutonniere."

The daguerreotypist is unknown, but may have been John Plumbe, Jr., whose studio Whitman often visited around this time. For more information on Plumbe, see "Notes on Whitman's Photographers."

Daguerreotypist: Plumbe, John, Jr., 1809–1857

Date: ca. 1848–1854

Technique: daguerreotype

Place: New York (N.Y.)

Subject: Whitman, Walt, 1819–1892 | New York (N.Y.)

Instance(s):

Metadata for Digital Item

Creator of master digital image: Walt Whitman Archive Staff

Rights: Public Domain. This image may be reproduced without permission.

Work Type: digital image

Date: ca. 2000–ca. 2006