Introduction to the 1855 Leaves of Grass Variorum

Introduction to the Variorum Edition of the 1855 Leaves of Grass

The first edition of Leaves of Grass, printed in 1855, is known to scholars and Whitman aficionados as a series of large, slim, predominantly green volumes.1 Bibliographical descriptions of the books note their contents: title page, copyright information (in most copies), portrait frontispiece, and text. The text includes a preface and twelve poems, untitled or (depending on one's definition of "title") with the first six poems printed under the recurring title "Leaves of Grass." The first poem is the longest, taking up 43 pages of the 96-page volume. The sheets of paper used for the book were probably printed on an iron hand press at Andrew Rome's printing shop in Brooklyn. Whitman would later claim that he had set ten pages of the type himself.2

This first version of Leaves of Grass had no publisher, no listed author, and no precedent. Its long lines of free verse and candid representations of the human body provoked an instant rebuke from many of its reviewers. "Reckless and indecent," it was called: "a mad book," "exceedingly obscene," "intensely vulgar," and "absolutely beastly."3 Of the poet, one reviewer wrote: "his very gait, as he walks through the world, makes dainty people nervous."4 Capping them all with his indignation in a scathing, unsigned review published in the Criterion, Rufus Griswold sputtered: "it is impossible to imagine how any man's fancy could have conceived such a mass of stupid filth, unless he were possessed of the soul of a sentimental donkey that had died of disappointed love."5

Critical opinions of Leaves of Grass had improved somewhat by the end of the century. But was it still Leaves of Grass? The book had grown on readers literally, as well as figuratively. By the time of Whitman's death in 1892, six separate, radically different editions of Leaves of Grass had been published. The final version of Leaves of Grass published in Whitman's lifetime, widely referred to as the "deathbed" edition, was more than 400 pages, several times the length of the first edition.6 The focus of early critics and readers, guided by the authorization of Whitman himself, tended to be this final, "complete" deathbed edition.7 But a resurgence of interest in the first edition in the last few decades of the twentieth century culminated in 2005 with a series of events dedicated to the 1855 copies, 150 years after their publication. This occasion and an associated 150th anniversary conference at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln led to the production of a collection of essays about the first edition titled Leaves of Grass: The Sesquicentennial Essays. The same year, Ed Folsom conducted a census of 158 surviving copies of the 1855 Leaves.8

Some of the differences among the printed copies of the 1855 Leaves of Grass were described in Folsom's census report and discussed further in the contributions by him and others to the Sesquicentennial Essays. These include a revision of a line of the poetry (probably by Whitman), a spelling correction in the preface, and differences in the size of the crotch in the frontispiece engraving, the latter of which Whitman scholars have discussed gleefully and at great length.9 The census also documented missing characters and line-end punctuation on some pages. Based on the census results, Folsom has speculated that "every copy of the first edition may be unique."10 One reason the copies of these books were distinct was because the printed gatherings were not bound consistently with the order of intentional changes to the text. Whitman did not, that is to say, keep the sheets on which the pages had been printed organized in a way that would have resulted in some copies all having only gatherings that were printed early in the press run, and other copies only gatherings that were printed late in the print run. In fact, some early printed gatherings were bound, seemingly randomly, with some later printed gatherings, so a single copy may contain both an uncorrected word and a revised line of poetry.11

Whitman also at some point decided to arrange for the printing of both a letter from Ralph Waldo Emerson praising Leaves of Grass and a series of reviews and extracts from critical essays previously published in periodicals. Whitman had written three of the reviews himself and published them anonymously. The Emerson letter was pasted and the reviews and extracts were bound into some copies of the 1855 Leaves, likely by Whitman, probably before they were distributed. The location of the items within the individual copies varies. The Emerson letter often is pasted to the front or back endpaper.12 In the majority of known surviving copies, the reviews and extracts were added at the front of the volume. In a small handful of others, they were added at the back.13 Individual copies have only become more distinct as time has progressed, as markings of ownership and regular wear and tear have introduced new annotations, new insertions, and new differences.

These variations, combined with a number of surviving manuscripts and notebooks that contributed to the poems and preface in the 1855 Leaves of Grass, suggested the fullest treatment of that edition had yet to be undertaken. As part of the New York University Press Collected Writings of Walt Whitman, a variorum of all the editions of Leaves of Grass was planned. It was originally supposed to cover all manuscript sources for poems as well as all variations of the poems as Whitman revised Leaves through his six very different editions. The original editors (Sculley Bradley and Harold W. Blodgett) gathered manuscripts, but eventually, when two additional editors (Arthur Golden and William White) joined the project, the decision was made to limit the variorum to only the printed poems. Other volumes in the Collected Writings printed early notebooks and prose manuscripts, but many of the poetry manuscripts never did appear in any of the project's 22 volumes. And because the three-volume variorum of printed editions of Leaves was organized around the final versions of the poems, that edition effectively buried the 1855 Leaves of Grass.

The decision to undertake a digital representation of the 1855 Leaves of Grass that would attempt to represent that edition as fully as possible—including manuscript and notebook antecedents—was made in part as a way to build upon and bring together this previous work. The best term that seemed to describe such an effort was "variorum edition," although this was not a conventional variorum. This digital edition, produced with the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities, is now available on the Walt Whitman Archive. It consists of four main parts: the text of the 1855 Leaves of Grass, including variants and insertions; the early manuscripts and notebooks; the reviews and extracts that were printed and bound into some copies; and a bibliography of known surviving copies.

This introduction provides a brief overview of Whitman's biographical history in the years leading up to the first publication of Leaves of Grass, as well as the printing, binding, distribution, and contemporary reception histories of the volumes. It surveys some of the manuscript and notebook antecedents, providing examples of the kinds of analysis this new variorum makes possible. It also discusses the evolution of several copies in the almost two hundred years since they were printed, including the markers of ownership they have accrued and the evidence of repurposing and reader response visible in some of them. It concludes with a reflection on the ways in which this project has reimagined the notion of the textual variorum, focusing on the many versions of printed and manuscript text, graphical and spatial elements, that comprise and inform this extraordinary first edition of Leaves of Grass.

I. Biographical History

Whitman's biographers have documented his activities and interests in the years leading up to the publication of the first edition of Leaves of Grass.14 Whitman began working as an apprentice in law, medical, and newspaper offices at an early age. By 1850, he had considerable experience writing and editing for the newspaper industry in New York and Brooklyn, and he had also worked as a printer, a schoolteacher, and a carpenter.15 He had traveled with his brother to New Orleans in 1848 for a short-lived stint as an editor of the New Orleans Crescent. He had published a number of journalistic articles, as well as periodical poems that stuck to conventional rhymes and topics. He had also published short pieces of fiction in several periodicals and a longer temperance novel called Franklin Evans.16 The knowledge he gained from each of these activities—of New York, and the United States more broadly; of politics, printing, law, medicine, carpentry, painting, and literature; of the lives of ferrymen, politicians, journalists, compositors, doctors, and lawyers—is apparent in the poems and prose that appeared in the first edition of Leaves of Grass.

In the early 1850s, after returning to New York, Whitman began to shift away from his work as a newspaper editor. After 1851, he began spending more time in house construction, the trade of his father, and real estate.17 In the late 1840s and early 1850s, he worked with contractors to build a series of houses in which his family lived, running a bookstore and printing shop out of the bottom of one of them.18 He continued to write poems and articles for periodical publication, however, including the revolution-inspired poem "Resurgemus," which was published in the New York Daily Tribune on June 21, 1850, and which Whitman revised for publication in the 1855 Leaves of Grass. As scholars have recently discovered, he also spent some of the early 1850s working again on fiction. In March and April 1852, he published the crime novel Life and Adventures of Jack Engle as a series of installments in the New York Sunday Dispatch.19

Probably in late 1854, Whitman began to focus in earnest on the production of the 1855 Leaves.20 Richard Maurice Bucke, in a biography heavily edited by Whitman, wrote that "Early in the fifties Leaves of Grass began to take a sort of unconscious shape in his mind. In 1854 he commenced definitely writing out the poems that were printed in the first edition…. Early in 1855 he was writing Leaves of Grass from time to time, getting it in shape. Wrote at the opera, in the street, on the ferry-boat, at the sea-side, in the fields, sometimes stopped work to write."21

Whitman probably wrote the poem later titled "A Boston Ballad" in 1854 in response to the case of Anthony Burns, a fugitive slave who was forcibly returned to the South under the terms of the controversial Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.22 The Whitman family moved to a house on Ryerson Street in May 1855. The title page for the 1855 Leaves of Grass was deposited on the fifteenth of that month, and the earliest known advertisement for the book appeared in June.23 On July 11, Whitman's father died after a long illness. Shortly after July 21, Whitman received the congratulatory letter from Ralph Waldo Emerson that was later printed and pasted into some copies of the 1855 Leaves of Grass. The earliest known review of the first edition of Leaves of Grass, unsigned but written by Charles A. Dana of the New York Tribune, was published in that paper on July 23. The book appeared in the Publisher's Circular under American books on October 15, 1855.

II. Manuscript and notebook antecedents

In his July 21 letter to Whitman, Emerson wrote: "I greet you at the beginning of a great career, which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere for such a start."24 This "long foreground" includes Whitman's journalistic work, his periodical poetry, his fiction, and his reading. Many keys to the foreground of Leaves of Grass may be found in the early manuscripts and notebooks. Scattered today across many different collections and repositories, these documents represent the foundations of the printed poems and prose. Some of them feature nearly final versions of lines. Others are brief, telegraphic notes.

These manuscripts share some general characteristics. They strikingly demonstrate, for example, how frequently Whitman revised across genre. Jotted notes, sometimes taken from external sources, sometimes become poetry, sometimes prose; prose becomes poetry; even, in a couple of cases, what look in manuscript versions like lines of poetry become segments of the prose preface.25 A comparison of the manuscripts and the printed text also makes it clear how often Whitman moved lines around, sometimes between poems.26 More often than not, Whitman reused the paper and wrote something on the backs of manuscript pages. This repurposing produced material connections among seemingly disparate projects. In the early notebooks, Whitman juxtaposed poetry drafts and notes toward the 1855 Leaves with lists of addresses and figures, clippings from newspapers, notes on reading, lists of words, notes about other writing projects, notes toward orations or "recitations," and, in at least one case, house measurements.27 This diversity of material reflects the range of his activities in the years leading up to the publication of the first edition.

By Whitman's own account, many of the manuscripts that contributed to Leaves of Grass were probably lost or destroyed. Surviving manuscripts and notebooks thus offer only a partial glimpse into the work involved in composing the poems, the preface, and the reviews. In later reflections published in the semi-autobiographical volume Specimen Days, Whitman would describe how he "[c]ommenced putting 'Leaves of Grass' to press for good . . . after many MS. doings and undoings—(I had great trouble in leaving out the stock 'poetical' touches, but succeeded at last."28 In a summary account included in his biography of Whitman, Bucke wrote that the poet "had more or less consciously the plan of the poems in his mind for eight years before, and that during those eight years they took many shapes; that in the course of those years he wrote and destroyed a great deal; that, at the last, the work assumed a form very different from any at first expected."29 "By the spring of 1855," Bucke concluded, "Walt Whitman had found or made a style in which he could express himself, and in that style he had (after, as he has told me, elaborately building up the structure, and then utterly demolishing it, five different times) written twelve poems, and a long prose preface which was simply another poem."30 In a later conversation with Traubel, Whitman said: "Bucke probably does not know that long long ago, before the 'Leaves' had ever been to the printer, I had them in half a dozen forms—larger, smaller, recast, outcast, taken apart, put together—viewing them from every point I knew—even at the last not putting them together and out with any idea that they must eternally remain unchanged."31

One of the manuscripts eventually lost or destroyed was evidently the complete "printer's copy" manuscript of the 1855 Leaves, given to Rome. In an 1888 conversation with Traubel, Whitman said: "You have asked me questions about the manuscript of the first edition. It was burned. Rome kept it several years, but one day, by accident, it got away from us entirely—was used to kindle the fire or to feed the rag man."32 Whitman's memory is consistent with a note added by Thomas Rome to the bottom of a printed, undated list of Whitman manuscripts for sale "in possession of T. H. Rome, 513 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn, N.Y." The note reads: "The manuscript of the first edition (1855) was accidentally destroyed in 1858."33

No evidence has surfaced to indicate that these recollections were false. One manuscript page now at the Library of Congress, however, may be either the only known surviving page from the printer's copy or, perhaps more likely, a discarded draft of a printer's copy page.

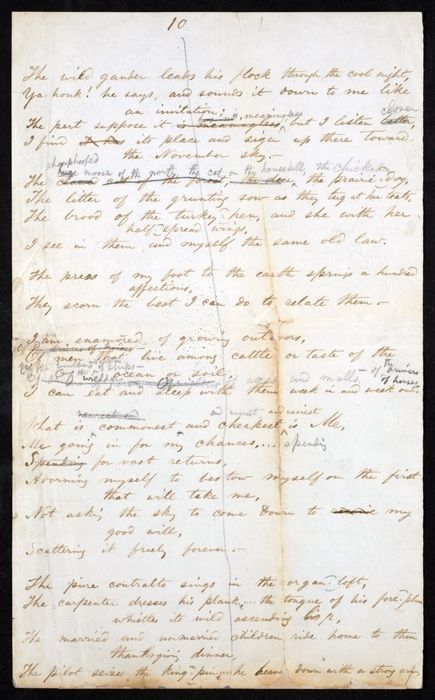

Figure.

"The wild gander leads his," a Whitman manuscript that may have been part or partial draft of a printer's copy of the 1855 Leaves of Grass. Charles E. Feinberg Collection, Library of Congress.

This manuscript features lines that appeared in the poem later titled "Song of Myself." The lines are in the correct order, but they do include a few differences from the printed text. Two stages of revision are visible: the first set of revisions, in ink, likely were done as Whitman was writing the manuscript. The second stage, in pencil, probably came later. John Broderick has described the manuscript as the last surviving page of "the original manuscript of the first edition of Leaves of Grass," a claim echoed by Arthur Golden.34 The number "10" at the top of the manuscript is not inconsistent with the possible positioning of these lines as page 10 of a printer's copy, but lacking further evidence it would be difficult to confirm. Whitman often used hash marks like the one drawn vertically through the lines on this leaf to indicate material had been used, rather than deleted. A list of terms written on the back of the manuscript leaf probably relate to the 1856 poem "Broad-Axe Poem." Given these characteristics and the extent of the revisions, perhaps the more likely explanation is that this was a page of the printer's copy that Whitman decided to re-write in a cleaner version, preventing this page from meeting the fate of the rest of the manuscript.

Figure.

"The wild gander leads his," a Whitman manuscript that may have been part or partial draft of a printer's copy of the 1855 Leaves of Grass. Charles E. Feinberg Collection, Library of Congress.

This manuscript features lines that appeared in the poem later titled "Song of Myself." The lines are in the correct order, but they do include a few differences from the printed text. Two stages of revision are visible: the first set of revisions, in ink, likely were done as Whitman was writing the manuscript. The second stage, in pencil, probably came later. John Broderick has described the manuscript as the last surviving page of "the original manuscript of the first edition of Leaves of Grass," a claim echoed by Arthur Golden.34 The number "10" at the top of the manuscript is not inconsistent with the possible positioning of these lines as page 10 of a printer's copy, but lacking further evidence it would be difficult to confirm. Whitman often used hash marks like the one drawn vertically through the lines on this leaf to indicate material had been used, rather than deleted. A list of terms written on the back of the manuscript leaf probably relate to the 1856 poem "Broad-Axe Poem." Given these characteristics and the extent of the revisions, perhaps the more likely explanation is that this was a page of the printer's copy that Whitman decided to re-write in a cleaner version, preventing this page from meeting the fate of the rest of the manuscript.

Even with its comparatively few revisions, this manuscript shows Whitman refining the balance of his lines, even up to the production of the printer's copy or a close draft. The lines form part of the section of the poem later titled "Song of Myself" that have the poet on a "distant and daylong ramble," observing and meditating on the creatures he sees.

| "The wild gander leads his" (Manuscript) | Leaves of Grass (Brooklyn, NY: 1855) |

| The wild gander leads his flock through the cool night, | The wild gander leads his flock through the cool night, |

| Ya-honk! he says, and sounds it down to me like an invitation; | Ya-honk! he says, and sounds it down to me like an invitation; |

| The pert suppose it |

The pert may suppose it meaningless, but I listen closer, |

| I find |

I find its purpose and place up there toward the November sky. |

| The |

The sharphoofed moose of the north, the cat on the housesill, the chickadee, the prairie-dog, |

| The litter of the grunting sow as they tug at her teats, | The litter of the grunting sow as they tug at her teats, |

| The brood of the turkey‑hen, and she with her half‑spread wings, | The brood of the turkeyhen, and she with her halfspread wings, |

| I see in them and myself the same old law. | I see in them and myself the same old law. |

| The press of my foot to the earth springs a hundred affections, | The press of my foot to the earth springs a hundred affections, |

| They scorn the best I can do to relate them.— | They scorn the best I can do to relate them. |

| I am enamored of growing outdoors, | I am enamoured of growing outdoors, |

|

|

Of men that live among cattle or taste of the ocean or woods, |

|

Of the builders ^and steerers of ships— |

Of the builders and steerers of ships, of the wielders of axes and mauls, of the drivers of horses, |

| I can eat and sleep with them week in and week out. | I can eat and sleep with them week in and week out. |

| What is |

What is commonest and cheapest and nearest and easiest is Me, |

| Me going in for my chances, . . . spending |

Me going in for my chances, spending for vast returns, |

| Adorning myself to bestow myself on the first that will take me, | Adorning myself to bestow myself on the first that will take me, |

| Not asking the sky to come down to |

Not asking the sky to come down to my goodwill, |

| Scattering it freely forever.— | Scattering it freely forever. |

| The pure contralto sings in the organ‑loft, | The pure contralto sings in the organloft, |

| The carpenter dresses his plank |

The carpenter dresses his plank . . . . the tongue of his foreplane whistles its wild ascending lisp, |

| The married and unmarried children ride home to their thanksgiving dinner, | The married and unmarried children ride home to their thanksgiving dinner, |

| The pilot seizes the king‑pin |

The pilot seizes the king-pin, he heaves down with a strong arm, |

The shift from "place and sign" in the fourth line of manuscript to "purpose and place" in the printed version of the line directs the ya-honk of the gander, alliterating and rebalancing the line. The revision from "sign" to "purpose" suggests intention beyond the comparative vision of symbolism, vectoring the gander's ya-honk toward a larger design, a vast tapestry of the natural world in which the poet imagines himself. This newfound "purpose" also resonates with the "winged purposes" of the wood-drake and wood-duck nine lines earlier in the poem: "I believe in those winged purposes, / And acknowledge the red yellow and white playing within me, / And consider the green and violet and the tufted crown intentional" (Leaves of Grass [1855], 20).

The internal revisions in the next line of the manuscript also show Whitman working to balance wild and domestic images. In the first manuscript version of the line ("The clawed cat of the forest, the deer, the prairie-dog,") the images are natural, with no hint of human presence. The final version of the line, juxtaposing the "sharphoofed moose of the north" with the "cat on the housesill," the chickadee with the prairie-dog, brings the images indoors, the poet tracking the creatures to the very doorsteps of their human neighbors. The shift from "men that live among cattle or taste of the ocean or soil" in the manuscript to "men that live among cattle or taste of the ocean or woods" in the printed line develops the fullness of a land-image to match the richness of the ocean that balances it and reverses the move from wildness to domesticity, moving from an agricultural to a natural image. The two short manuscript lines "Me going in for my chances, / Spending for vast returns," are transformed in a penciled revision into the single line "Me going in for my chances, spending for vast returns," balancing the line lengths and evening out the stanza.35 These revisions suggest there was probably at least one more manuscript version between this draft and the printed copy, or (less likely) that Whitman could have been revising in type, if this was among the pages he claimed to have set himself.

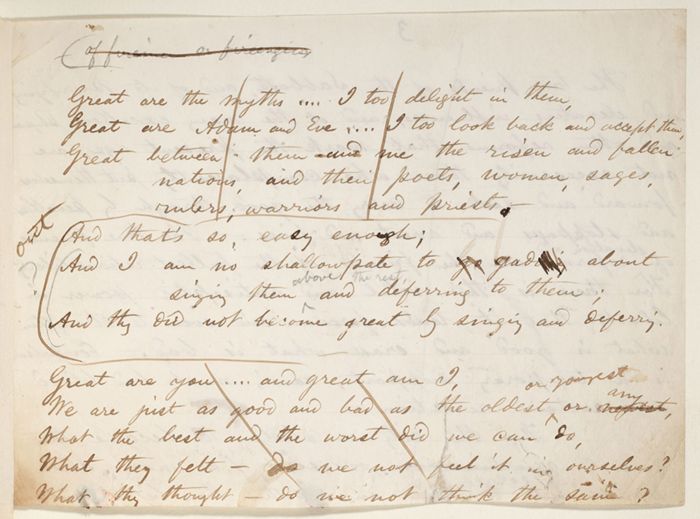

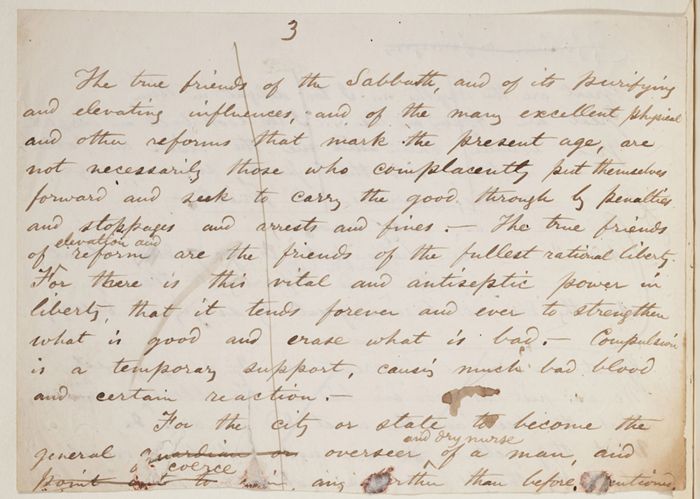

Several of the manuscripts and notebooks also reflect other projects Whitman was working on around the same time. Four separate early poetry manuscripts (now held at Duke, New York Public Library, Library of Congress, and in a private collection) are written on the back of partial drafts of "Memorial in Behalf of a Freer Municipal Government, and Against Sunday Restrictions," delivered to the Brooklyn City Council as a public letter and later published in the Brooklyn Evening Star on October 20, 1854.36 Three sets of the poetic lines relate to parts of the 1855 poems eventually titled "Great are the Myths" and "Song of Myself." The final set (on the manuscript at the New York Public Library) does not have any known relation to Whitman's published poetry.

Whitman marked through each of the "Sunday Restrictions" segments, perhaps indicating that the material had been used.37 This and the situation of the text on the manuscripts (particularly the way the edges were clipped) suggests that the poetic lines may have been written after the prose.

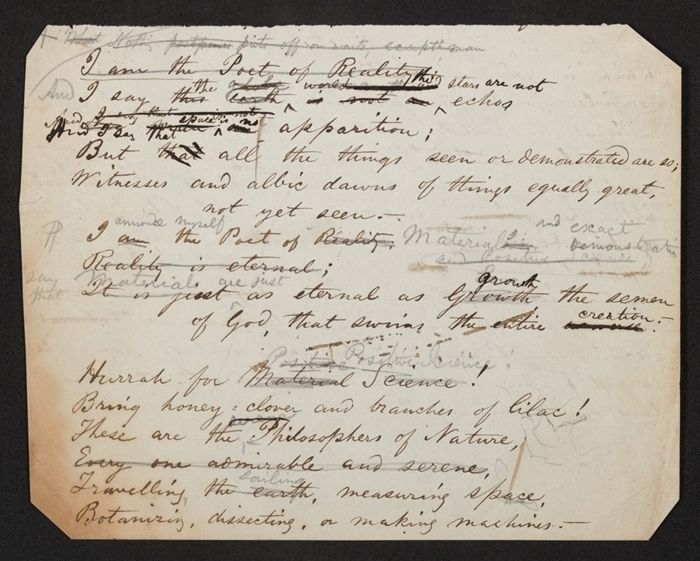

Figure.

Recto and verso of "And I say the stars." Lines on one side of this manuscript were used in the poems later titled "Song of Myself" and "To Think of Time." The text on the reverse is a partial draft of "Sunday Restrictions." Charles E. Feinberg Collection, Library of Congress.

Assuming Whitman drafted "Sunday Restrictions" shortly before it was delivered and published, this would suggest that the lines were written late in 1854 or early in 1855. One set of lines, on the Duke manuscript "Great are the myths," corresponds to lines in the poem eventually titled "Great are the Myths" (later shortened and retitled "Youth, Day, Old Age, and Night"), and here the lines he revised and used in the 1855 version of the poem are also marked through:

Figure.

Recto and verso of "And I say the stars." Lines on one side of this manuscript were used in the poems later titled "Song of Myself" and "To Think of Time." The text on the reverse is a partial draft of "Sunday Restrictions." Charles E. Feinberg Collection, Library of Congress.

Assuming Whitman drafted "Sunday Restrictions" shortly before it was delivered and published, this would suggest that the lines were written late in 1854 or early in 1855. One set of lines, on the Duke manuscript "Great are the myths," corresponds to lines in the poem eventually titled "Great are the Myths" (later shortened and retitled "Youth, Day, Old Age, and Night"), and here the lines he revised and used in the 1855 version of the poem are also marked through:

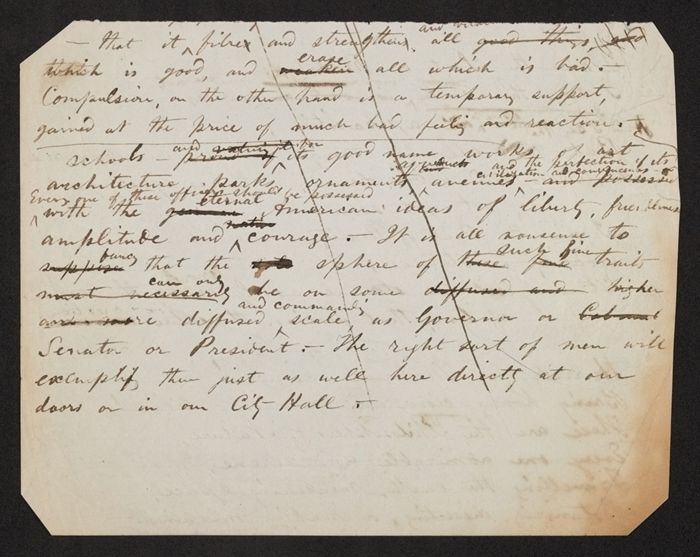

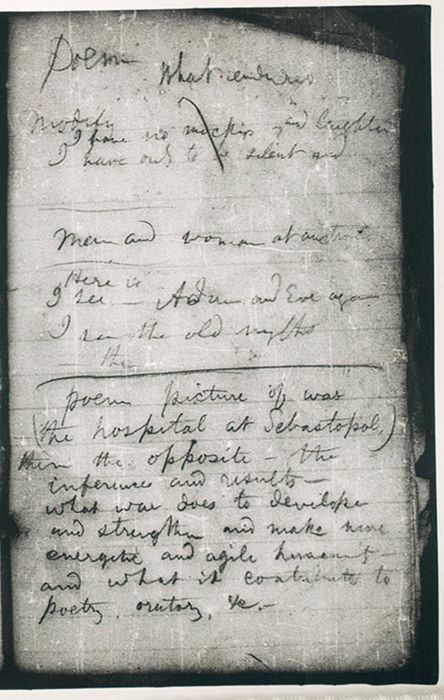

Figure.

Recto and verso of "Great are the myths," with draft lines written on the back of a partial draft of "Sunday Restrictions." Duke University. Several of the lines, including "Great are the myths . . . . I too delight in them, / Great are Adam and Eve . . . . I too look back and accept them," were used in the 1855 Leaves of Grass.

These lines are similar to the text that appeared in the printed edition. They are clearly later drafts of the lines than a related set that appeared in "women," a notebook with content probably dating to about 1854. Text in the notebook contributed to various published pieces, including a set of Whitman's notes about his visits to the Egyptian Museum that would inform the prose piece "One of the Lessons Bordering Broadway: The Egyptian Museum," which was published in Life Illustrated on December 8, 1855. In the notebook, the draft lines related to "Great are the Myths" are written on a page just under early drafts of lines that appeared in the poems later titled "Song of Myself" and "I Sing the Body Electric":

Figure.

Recto and verso of "Great are the myths," with draft lines written on the back of a partial draft of "Sunday Restrictions." Duke University. Several of the lines, including "Great are the myths . . . . I too delight in them, / Great are Adam and Eve . . . . I too look back and accept them," were used in the 1855 Leaves of Grass.

These lines are similar to the text that appeared in the printed edition. They are clearly later drafts of the lines than a related set that appeared in "women," a notebook with content probably dating to about 1854. Text in the notebook contributed to various published pieces, including a set of Whitman's notes about his visits to the Egyptian Museum that would inform the prose piece "One of the Lessons Bordering Broadway: The Egyptian Museum," which was published in Life Illustrated on December 8, 1855. In the notebook, the draft lines related to "Great are the Myths" are written on a page just under early drafts of lines that appeared in the poems later titled "Song of Myself" and "I Sing the Body Electric":

Figure.

Photocopy of a notebook page from women, a notebook once held at the Library of Congress, now lost. The poem-notes "I see Here is—Adam and Eve again / I see the old myths" are probably early drafts of the lines that appear in the Duke University manuscript.

Figure.

Photocopy of a notebook page from women, a notebook once held at the Library of Congress, now lost. The poem-notes "I see Here is—Adam and Eve again / I see the old myths" are probably early drafts of the lines that appear in the Duke University manuscript.

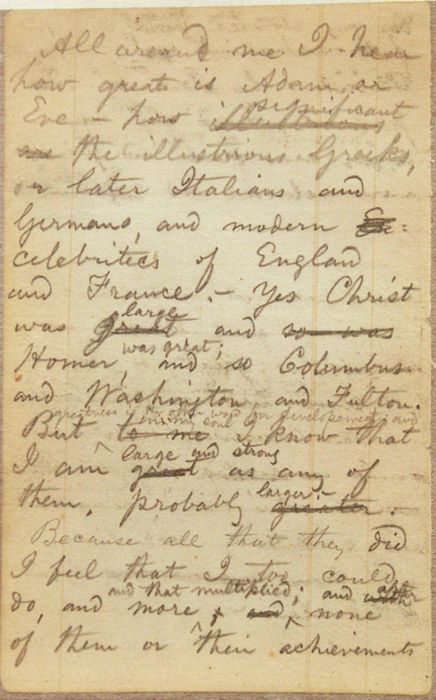

We have also connected the starting lines of what would become "Great are the Myths" to "Poem incarnating the mind," a notebook with some material written around 1854 but other material that may date earlier. The notebook includes other lines that were used in the 1855 and 1856 editions of Leaves of Grass, as well as what appears to be a note relating to one of Whitman's early pieces of fiction. In this notebook Adam and Eve appear as part of a prose draft:

Figure.

Page from "Poem incarnating the mind" notebook, ca. 1850s. The section "All around me I hear how great is Adam or Eve" may be early thoughts toward the "Great are the Myths" lines.

The three contexts in which these draft lines and notes appear are considerably different. Readers tracing these kinds of connections will no doubt find much to say about the roots of Whitman's poems in the rich context of his thinking about religions, wars, cultural histories, and the political events of his time. But they also show Whitman's lines emerging out of notes in various genres, and in the midst of a number of different writing projects and daily activities.

Figure.

Page from "Poem incarnating the mind" notebook, ca. 1850s. The section "All around me I hear how great is Adam or Eve" may be early thoughts toward the "Great are the Myths" lines.

The three contexts in which these draft lines and notes appear are considerably different. Readers tracing these kinds of connections will no doubt find much to say about the roots of Whitman's poems in the rich context of his thinking about religions, wars, cultural histories, and the political events of his time. But they also show Whitman's lines emerging out of notes in various genres, and in the midst of a number of different writing projects and daily activities.

As this set of manuscripts also demonstrates, multiple drafts exist for many of the lines in the 1855 poems. The manuscripts that have survived likely represent only a small fraction of the manuscripts that once existed. Yet we can still begin to assess lines and segments of poems that were clearly sites of several rounds of revision or iteration for Whitman—doings and undoings—sometimes within and sometimes across manuscripts and notebooks. These include sections on the "trained soprano," touch, and the poet ascending a hill in the poem later titled "Song of Myself" and sections about "Lucifer" and "journeymen divine" in the poem later titled "The Sleepers." Some of these sections have been explored at length by Whitman scholars; others remain to be explored, perhaps with reference to the revisions and manuscript connections represented in the variorum.

One important cluster of possibly early manuscripts has been excluded from the variorum at the present time. This is a cluster relating to the manuscript poem "Pictures," the fullest expression of which is a handmade notebook now located at Yale University. Emory Holloway, who first wrote at any length about the manuscript and created a printed edition of it, speculated based on connections to the 1855 Leaves of Grass that it was an early notebook, "pre-natal" to Leaves, probably dating to around 1850.38 Harold Blodgett and Sculley Bradley followed suit in calling "Pictures" "an important preliminary, a kind of auspice of [the 1855 Leaves of Grass]."39 But Edward Grier has pointed out that Whitman used the paper on which the notebook was written—bearing the stamp of Owen & Hurlbut—for other manuscripts dated 1859 and 1860, and that some of the manuscripts that seemingly contributed to "Pictures" were written on leftover wrappers from the 1855 Leaves of Grass, suggesting the manuscript poem dates later.40 Although there are some similarities between the lines that appear in the Yale version of "Pictures" and the text of the 1855 edition, with one exception the similarities are not extensive enough to assert that any lines in "Pictures" are drafts or versions of the 1855 lines.41 Because there is a good chance that the Yale version of the manuscript was written after 1855 and because a closer treatment of the various manuscripts related to the idea of "Pictures" is warranted as an edition in its own right, we have elected not to include "Pictures" relations in the variorum at this time.

III. Printing History

The story of the printing of the 1855 Leaves of Grass has evolved over time, drawing on Whitman's own statements, the known production history of the volumes, evidence in surviving manuscripts, family history and anecdotes, and some informed speculation. Whitman commissioned the printing of the volumes by Andrew Rome at Rome's printing shop shortly after Andrew's brother James's death in 1854. Rome, a Scottish immigrant who had run the business with his brother, mostly printed functional documents like legal forms. In later years, the firm also printed pamphlets and other books of prose and poetry.42 Whitman had probably met the Rome family several years earlier.43 Other Rome siblings may have been involved in the production of the book, particularly Thomas Rome, who was ten years younger than Andrew and would eventually join his brother in managing the shop.44 Whitman would later claim that he himself set ten pages of the type for the first edition of his book of poems.45

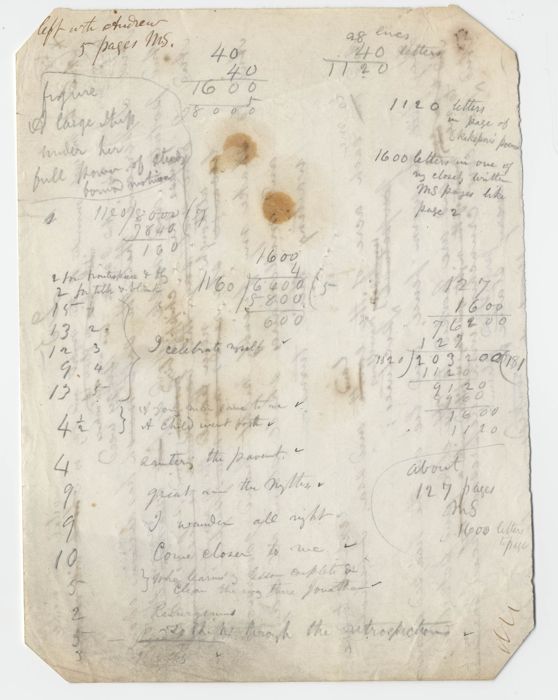

Manuscript evidence offers a glimpse into Whitman's planning process for the job. He diagrammed an early draft of the structure of the book on a manuscript now held at the University of Texas.

Figure.

"left with Andrew," a Whitman manuscript with calculations and a draft outline related to the 1855 Leaves of Grass. Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

On this manuscript leaf, Whitman created an outline of the intended order for his poems (in a sequence that differs from the final printed sequence of the 1855 edition) and added up the number of manuscript pages associated with each. He then estimated the letters in "one of my closely written MS pages like page 2," multiplied that count by the pages of manuscript (127), then divided by the number of letters on a printed page of poetry (in this case, Shakespeare's), to estimate 181 printed pages.

Figure.

"left with Andrew," a Whitman manuscript with calculations and a draft outline related to the 1855 Leaves of Grass. Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

On this manuscript leaf, Whitman created an outline of the intended order for his poems (in a sequence that differs from the final printed sequence of the 1855 edition) and added up the number of manuscript pages associated with each. He then estimated the letters in "one of my closely written MS pages like page 2," multiplied that count by the pages of manuscript (127), then divided by the number of letters on a printed page of poetry (in this case, Shakespeare's), to estimate 181 printed pages.

Based on the Texas manuscript, Folsom has suggested that the unusual size of the pages of the 1855 Leaves was probably the result of what the Rome brothers had on hand (paper suitable for legal forms), rather than Whitman's own choice. The elimination of white space and "Leaves of Grass" headings for the untitled poems as the book progresses has been attributed to Whitman's realization that he was running out of space and would need to conserve it to fit all of the poems within a limited number of pages.46 The preface has been viewed as a last-minute addition, introduced when Whitman had to recalculate after realizing that the page size would differ from what he had expected.47

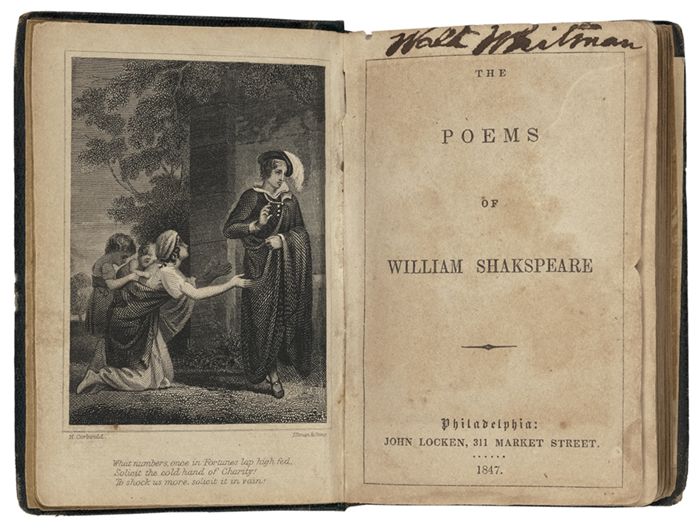

The Texas manuscript does suggest that Whitman was almost certainly not expecting to work with the page size that he ended up with for the 1855 Leaves of Grass. His estimate of 1120 letters on a page of Shakespeare's poems is based on a count of 28 lines per page and 40 letters per line. This count is a close match to Whitman's own copy of an octavo edition of Shakespeare's poems, published in 1847 in Philadelphia.

Figure.

Title page from Whitman's copy of The Poems of William Shakspeare (Philadelphia: John Locken, 1847). Height 12 cm (compare to approximately 28 cm height for the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass). PR2841 1847a copy1 Sh.Col. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Figure.

Title page from Whitman's copy of The Poems of William Shakspeare (Philadelphia: John Locken, 1847). Height 12 cm (compare to approximately 28 cm height for the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass). PR2841 1847a copy1 Sh.Col. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Figure.

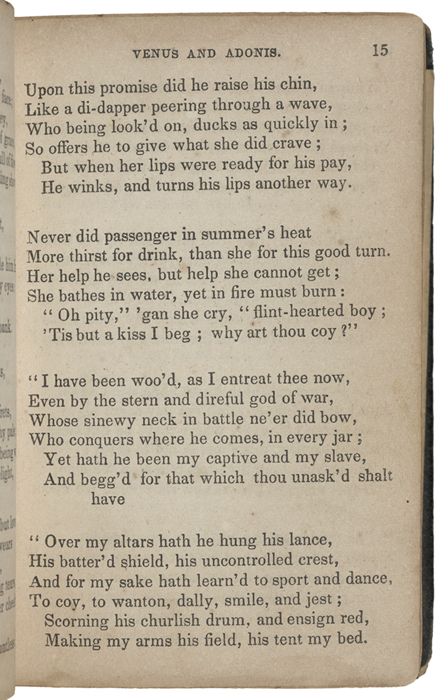

Page 15 of The Poems of William Shakspeare (Philadelphia: John Locken, 1847). This page features 28 lines (including blank and partial lines) and 40 characters per line in several of the lines (including spaces and punctuation marks), matching Whitman's estimate of 28 lines per page and 40 letters per line. PR2841 1847a copy1 Sh.Col. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

At some point, Whitman must have realized that he would need to work with a much larger page size than he had planned. But because the paper used for the edition could have been folded at least one more time, paper size alone is unlikely to have dictated the dimensions of the pages of the book. More likely, the final dimensions had something to do with concurrent printing or the available type, furniture, and other machinery in Rome's shop.48

Figure.

Page 15 of The Poems of William Shakspeare (Philadelphia: John Locken, 1847). This page features 28 lines (including blank and partial lines) and 40 characters per line in several of the lines (including spaces and punctuation marks), matching Whitman's estimate of 28 lines per page and 40 letters per line. PR2841 1847a copy1 Sh.Col. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

At some point, Whitman must have realized that he would need to work with a much larger page size than he had planned. But because the paper used for the edition could have been folded at least one more time, paper size alone is unlikely to have dictated the dimensions of the pages of the book. More likely, the final dimensions had something to do with concurrent printing or the available type, furniture, and other machinery in Rome's shop.48

Figure.

Approximation of page layout on a printed sheet used for the 1855 Leaves of Grass.

Figure.

Approximation of page layout on a printed sheet used for the 1855 Leaves of Grass.

As Folsom points out, the Texas manuscript also raises some questions about what exactly was included in Whitman's plan for the book. Whitman calculates based on 127 pages of manuscript, but only 113.5 pages of manuscript are accounted for by the list of contents to the left of the page. The two pages devoted to the frontispiece and fly and the two pages devoted to the title page and "blank" probably would not have been included in the calculations, since they did not include text that would need to be incorporated into the count of letters. Folsom has posited that the difference was a calculation error that created space for the preface.49 And yet several factors suggest that the preface was planned before the printing began and that the sheets were printed in order, including the layout of the second gathering (with pp. ix–xii of the preface printed on the same sheet as pp. 13–16 of the poetry), the headlines with pagination numerals (which start with 14 on the second page of poetry), and the stop-press correction of "adn" to "and" on p. iv of the preface (no stop-press corrections are known to exist in the gatherings that make up the second half of the book).

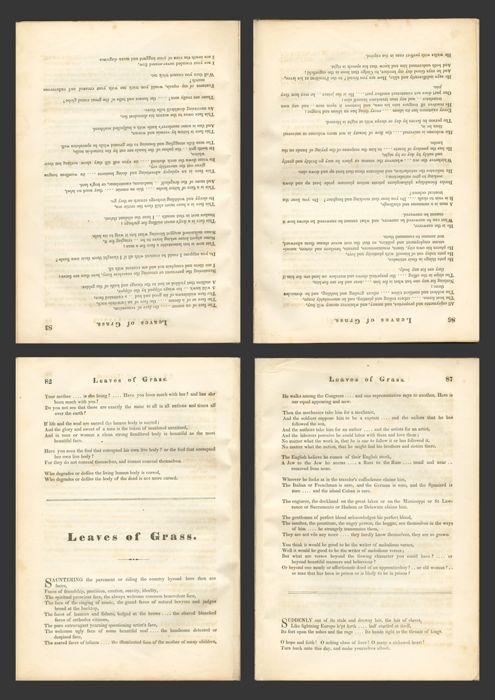

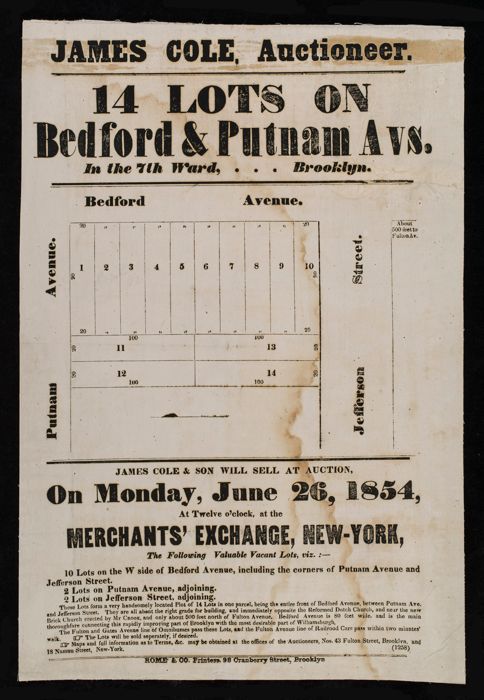

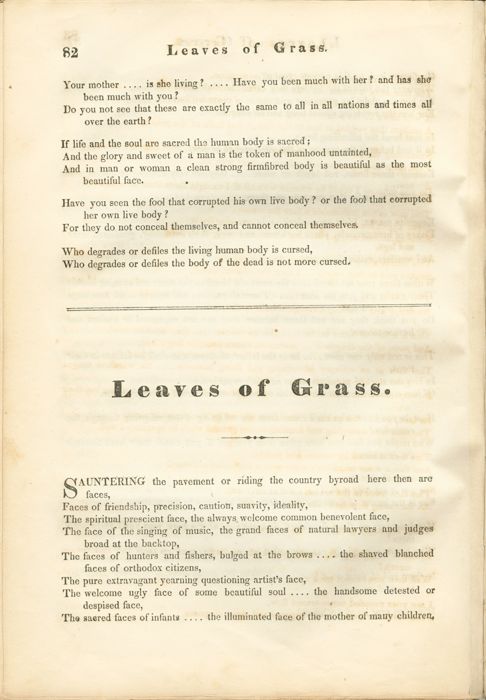

In the production and the layout of the book, Whitman probably was limited by the available type and the printing setup at Rome's shop. The press was likely an iron hand press, perhaps the popular and sturdy Washington press, which the Rome brothers could have gotten second-hand.50 A broadside circular issued by Rome in 1854 provides one example of the kind of printed material the firm produced around the time of printing Leaves of Grass, and the printing quality is similar.51

Figure.

1854 broadside circular printed by Rome. Original dimensions are approximately 17 7/8" high by 12" wide. Broadsides SY1854 no.64. New York Historical Society.

Figure.

1854 broadside circular printed by Rome. Original dimensions are approximately 17 7/8" high by 12" wide. Broadsides SY1854 no.64. New York Historical Society.

Figure.

Page 82 of Leaves of Grass (1855). Special Collections, The University of Iowa Libraries. Original dimensions are approximately 11" high by 7 3/4" wide.

Figure.

Page 82 of Leaves of Grass (1855). Special Collections, The University of Iowa Libraries. Original dimensions are approximately 11" high by 7 3/4" wide.

Figure.

Approximate comparison of broadside and 1855 Leaves of Grass pages by dimension. Images are not to scale.

The broadside has several compositional errors, including punctuation ("Bedford Avenue is 80 feet wide. and is the main thoroughfare" etc.), spelling ("the Fulton Avenue line of Railrood Cars . . . "), and either spelling or a turned letter (". . . pass within two minntes' walk"). In time and as he branched out into other kinds of projects Rome must have improved his practice: by the 1860s, the printing looks more consistent in pamphlets and books printed by Rome Brothers.52

Figure.

Approximate comparison of broadside and 1855 Leaves of Grass pages by dimension. Images are not to scale.

The broadside has several compositional errors, including punctuation ("Bedford Avenue is 80 feet wide. and is the main thoroughfare" etc.), spelling ("the Fulton Avenue line of Railrood Cars . . . "), and either spelling or a turned letter (". . . pass within two minntes' walk"). In time and as he branched out into other kinds of projects Rome must have improved his practice: by the 1860s, the printing looks more consistent in pamphlets and books printed by Rome Brothers.52

We can also speculate that Whitman's elimination of the white space and eventually the "Leaves of Grass" headings before some of the poems may have been the product of his inability to calculate an approximation of the number of pages the poems would take up based on a convenient model. When he was imagining a smaller volume, he had a nearby example—Shakespeare's poems, which he could use to estimate the number of letters on a printed page and thus the number of pages his manuscript might reach when printed. But there were no convenient examples of a printed book of poetry the size Whitman's ended up being, and thus no reliable way to cast off the copy. As Folsom has pointed out, Whitman probably realized the poems would take up more room than he had expected after the eighth signature had been set in type. The first sign of space conservation happens on page 70, in the ninth gathering, when the next poem (later titled "The Sleepers") begins directly after the end of the previous poem (later titled "To Think of Time").

Whatever the specific dynamics of printing and proofing, Whitman was clearly actively involved in the edition's production. Moncure Conway's experience during a late summer visit to Whitman suggests the familiarity of the poet with Rome's shop. In a letter to Emerson dated September 17, 1855, Conway wrote of Whitman: "His mother directed me to Rome's Printing Office (corner Fulton and Cranberry Streets) . . . where he often is. I found him revising some proof. A man you would not have marked in a thousand; blue striped shirt, opening from a red throat; and sitting on a chair without a back, which, being the only one, he offered me, and sat down on a round of the printer's desk himself."53 This visit would have happened after the pages of the book had all been printed, so Whitman must have been revising some other proof at that time. But Whitman or someone else at the print shop did evidently proof the pages of Leaves of Grass as they were coming off the press, which produced a couple of stop-press changes in the first 49 pages of text. It is not clear whether Whitman proofed the whole book as it came off the press. No intentional changes have been located after page 49. Other kinds of variation are visible throughout the books, however, many of which are probably differences due to mechanical or printing phenomena like shifting type or inking inconsistencies.

IV. Variants, Insertions, and Bindings

For the purposes of this digital edition, we have divided the differences observed among copies of the 1855 Leaves of Grass into three categories: 1) textual and graphical variants, or variants that involve missing, changed, or added characters in text or observable differences in images; 2) bindings and insertions; and 3) selected spatial variants, or differences in spacing between characters or words that probably were the result of shifting type.

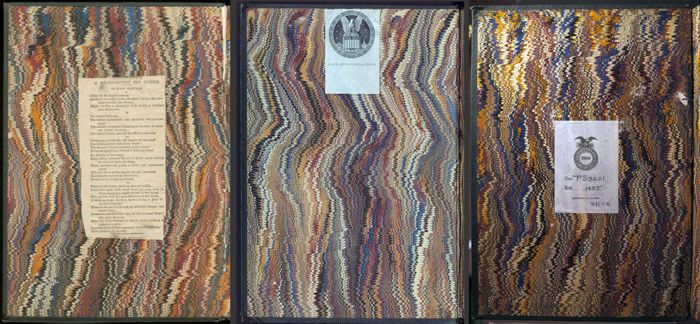

The different bindings used for the edition have been described at some length in bibliographies of Whitman, including Michael Winship's Whitman section of the Bibliography of American Literature and Joel Myerson's Walt Whitman: A Descriptive Bibliography.54 These bibliographies list three distinct bindings, descriptions of which are provided in the variorum annotations and in the linked bibliography of copies. Some additional differences occur within the bindings, including for instance the different paper wrappers in binding C.55 Other differences are the product of the processes used to produce the materials used to bind the books, like the natural variations in the marbled paper used for endpapers in copies with binding A.

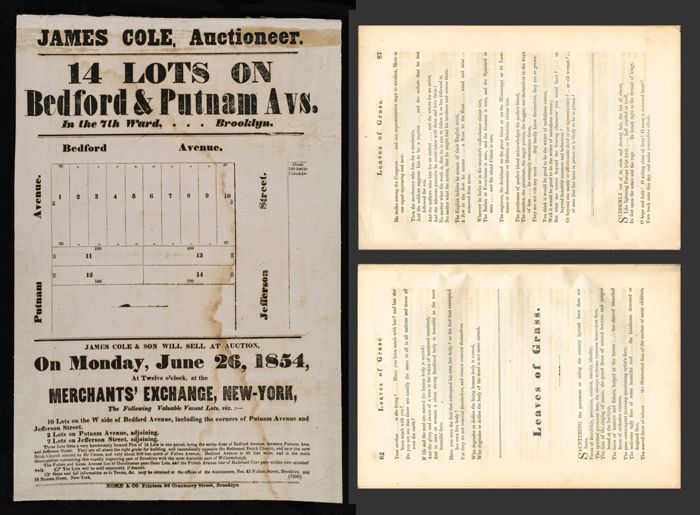

Figure.

Front pasted-down endpaper from copies in Special Collections, The University of Iowa Libraries (UI_01), the Library of Congress Houghton Collection (LC_01), and the Library of Congress (LC_03), respectively.

Some copies in binding B also feature reversed blind-stamped ornaments in the center of the front and back covers. This probably corresponds to the different stages of this binding described in the binder's statement.56

Figure.

Front pasted-down endpaper from copies in Special Collections, The University of Iowa Libraries (UI_01), the Library of Congress Houghton Collection (LC_01), and the Library of Congress (LC_03), respectively.

Some copies in binding B also feature reversed blind-stamped ornaments in the center of the front and back covers. This probably corresponds to the different stages of this binding described in the binder's statement.56

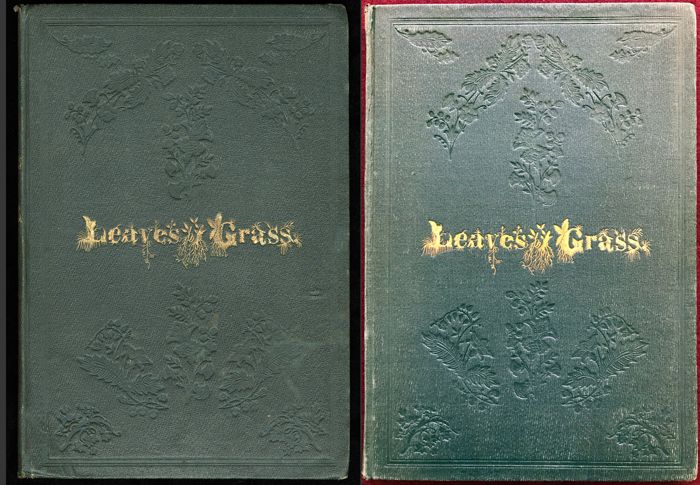

Figure.

The blind-stamped ornaments at the center of the cover, just above and below the gold-stamped title, are reversed in some state B copies. Copies at the University of Virginia (UVa_05) and the Library of Congress (LC_07), respectively.

Figure.

The blind-stamped ornaments at the center of the cover, just above and below the gold-stamped title, are reversed in some state B copies. Copies at the University of Virginia (UVa_05) and the Library of Congress (LC_07), respectively.

Also classified as "Bindings and Insertions" in the variorum are printed slips or newspaper clippings with a transcription of the letter from Ralph Waldo Emerson, often pasted to an endpaper, and a series of contemporary reviews and extracts from longer essays, which Whitman had printed as an eight-page insertion that was bound into some copies of the 1855 Leaves of Grass. We have included the frontispiece leaf within the "Bindings and Insertions" category because both states involved an inserted sheet of heavy paper, and in one state the frontispiece was a chine collé print on thin paper that was pasted onto the heavier paper.57 Several copies in binding A have a label with a London address pasted onto the title page. Myerson lists the London copies as a second (English) issue (A 2.1.a2). In at least one copy, the London label has a textual variant (the name "William" is spelled out rather than abbreviated as "Wm."). These differences have also been described within "Bindings and Insertions."

The known textual and graphical variants in the copies that make up the first edition of Leaves of Grass are relatively few, and for the most part have been described in earlier studies of the edition.58 Some changes seem clearly to be purposeful. Ted Genoways has written about the alterations made to the crotch and pant leg of the engraving used for the frontispiece. The original engraving used to print the frontispiece image has often been attributed to Samuel Hollyer, who was working from a daguerreotype produced by Gabriel Harrison in July 1854. Genoways has suggested that the engraving may instead have been the work of John C. McRae, despite Hollyer's later description of his alterations of the plate at Whitman's request.59 There are clearly two different states of the frontispiece, one of which has additional incremental variations.60 Genoways argues that Whitman intended this change to make the frontispiece figure better "match his exaggerated persona" in the poems (100). Many contemporary reviewers remarked upon the frontispiece, functioning as it did as a stand-in for the author's name, which did not appear on the title page of the book.61

In most surviving copies, the copyright statement for the 1855 Leaves of Grass is printed in two lines on the verso of the title page. In two copies Whitman wrote the notice in by hand, however, and in one copy the verso of the title page is blank.62 Both Winship and Myerson posit that the blank or handwritten version is an earlier state, and the printed version is later, a sequence which is consistent with the presence of the latter in the vast majority of surviving copies.63 Whitman may not have added it until after he went to deposit the title page and got a draft of the wording from George F. Betts, a clerk in the Southern District of New York.64 Because there are slight variations between the two handwritten versions of the statement, we have included both in the variorum.

Scholars also have noted two intentional corrections to the text. On page iv of the preface, a misspelled "adn" is corrected to "and" in some copies. And on page 49, two versions of a line in the poem eventually titled "Song of Myself" have been observed: "And the night is for you and me and all" and "And the day and night are for you and me and all." Folsom has argued that "the night" was the earlier version and that this change, almost certainly made by Whitman, brings that line into keeping with other lines that balance day and night in Leaves of Grass.65

Other textual variations may have been the result of inconsistent inking, type batter, shifting type, or frisket bite. These include a missing period and a missing "n" at the bottom right corner of page vi of the preface in some copies, a missing "I" at the end of the phrase "the ward and city I" on page 15, a missing ";" after the word "love-grip" on page 32, and a missing period at the end of the poem later titled "Song of Myself" on page 56.66 With the exception of the period on page 56, these variations appear at the edges or corners of pages. The absent period on page 56—actually present in some copies—has had an outsized presence in literary criticism, suggesting the ways in which textual variants among the copies have been interpreted as significant to the meaning of the poems. Golden and Folsom have pointed out the critical studies that engaged the missing period as a poetic rather than a printing phenomenon.67

Remaining variations we have noted among the copies and included in the variorum are described as spatial variants and most likely were caused by shifting type. It should be emphasized that we have not attempted to record and represent every such variation. The inking and typographical spacing in the books vary widely. The subset of spatial variations represented in the variorum was selected as an illustration of the broader phenomenon. The selected variants have two discernible states, each of which has been observed in at least three copies. They include the following:

| Page | Text | Description |

| p. 15 | Leaves of Grass. | The "es" in the running head is spaced more widely in some copies than in others. |

| p. 45 | Admitting they were | In some copies the first characters in the word "Admitting" drop below the line of type. |

| p. 47 | Whatever interests the rest interests me . . . . politics, churches, newspapers | In some copies this line is spaced more widely than in others. |

| p. 50 | long and long. | In some copies the final "g." is printed above the rest of the line. |

| p. 66 | Witty, sensitive to a slight | In some copies there is more space before "Witty." |

| p. 93 | Wealth with the flush hand | In some copies there is more space between "W" and "ealth." |

These differences, often appearing at the edges or corners of pages, involve both white space and printed characters. They probably were not the result of human intention, but simply a by-product of the press and the way the book was printed.

The image comparison viewer included as part of the variorum offers a way to view side-by-side images of variants, insertions, and bindings in the University of Iowa copy and various other copies. The copy information associated with each image can be found by clicking the small "i" in the upper right corner of any image window. For the viewer, in some cases, we have provided multiple images associated with a single variant or binding, so that the user of the variorum can see, for instance, different color paper wrappers used in binding C, different marbling on the endpapers used in binding A, various placements of the London label on the title page, and slight variations in the descender of the "u" on page 56.

V. Distribution and reception

Most of the printing related to the first edition of Leaves of Grass was completed by the summer of 1855.68 The first stage of binding happened in June. Several of the copies were offered for sale at stores in New York and Brooklyn after they were printed and bound.69 In later accounts, Whitman spoke often (and likely with some exaggeration) of the books' failure to sell. In an 1888 conversation with Traubel, he said of the first edition "I don't think one copy was sold—not a copy . . . . The books were put into the stores. But nobody bought them. They had to be given away. But the ones we sent them to—a good many of them—sent them back—did not want them even on such terms."70 Some copies were sent directly to editors of newspapers and magazines, and others were reportedly sent to "prominent literary men."71

The first edition probably consisted of between 795 and 1000 copies.72 A statement written by Brooklyn bookbinder Charles Jenkins, detailing work by himself and Davies & Hands to bind the volumes, indicates that 795 copies of the book were bound: 599 in cloth, and the rest in paper or boards. Some cloth bindings featured gilt edges, goldstamped title and borders, blindstamped floral ornaments, and marbled endpapers (binding A). Others only had a goldstamped title, blindstamped borders and ornaments, plain edges, and peach, buff, or yellow endpapers (binding B).

The books were sold by the phrenological firm Fowlers & Wells, which became Fowler & Wells in September 1855 when Orson Fowler left the firm.73 Whitman had become acquainted with the Fowlers in the late 1840s as a result of his interest in phrenology, and Lorenzo Fowler conducted a phrenological exam of the poet in 1849. As Madeleine Stern has pointed out, Fowler's assessment deeply influenced the poet and his writing, likely providing one source of the phrenological vocabulary he used in the preface and poems.74 Whitman kept the chart and extended phrenological description from the exam until the end of his life and published notes from it in three editions of Leaves of Grass, including as part of the reviews and extracts insertion in some copies of the 1855 edition.75 As a bookseller in the early 1850s, Whitman had sold books and other publications produced by Fowlers & Wells.76 In the year after the publication of the first edition of Leaves, Whitman became a regular contributor to the Fowler & Wells periodical Life Illustrated, publishing pieces in various issues between November 1855 and August 1856.77 Draft material for at least one of these pieces appears in a notebook next to draft lines that would end up in the 1855 Leaves of Grass.78 As Allen has pointed out, the periodical also proved to be an important vehicle for publicity for Leaves of Grass. Life Illustrated would feature and reprint several reviews of the 1855 Leaves.79

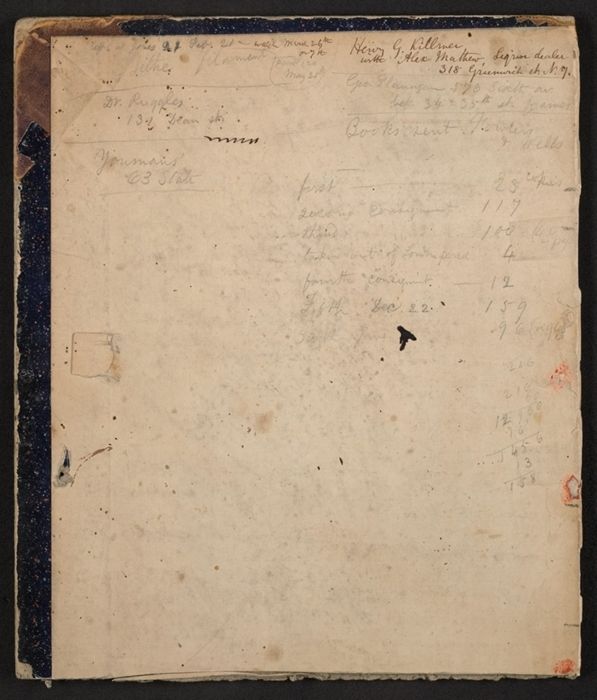

A list that appears on what once was probably the front cover of a scrapbook, now held at the Library of Congress, gives some sense of Whitman's side of the distribution of copies of the 1855 Leaves of Grass by Fowler & Wells.

Figure.

Cover with Whitman's notes about consignments sent to Fowler & Wells. Charles E. Feinberg Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Whitman labeled the list "Books sent Fowlers & Wells"80 and under this listed a series of consignments:

Figure.

Cover with Whitman's notes about consignments sent to Fowler & Wells. Charles E. Feinberg Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Whitman labeled the list "Books sent Fowlers & Wells"80 and under this listed a series of consignments:

| first --------------------------- | 23 copies |

| second consignment | 117 |

| third | 100 (40 in paper |

| taken out of London parcel | 4 |

| fourth consignment ---------- | 12 |

| Fifth Dec. 22 | 159 |

| Sixth Jan | 96 (or 94 |

These figures (totaling 511 or 509) are roughly consistent with the dates of the various stages of binding described in the binder's statement.81

As this list of consignments suggests, copies of the first edition of Leaves of Grass circulated in the United States and in England. The copies in England were initially distributed by William Horsell and Company, health reformers and London agents of Fowler & Wells, and a printed slip with their address is pasted to the title page in several copies.82 The books Horsell could not sell were later picked up by an itinerant book trader, James Grindrod, who sold a copy to Thomas Dixon, a Sunderland cork-cutter.83 Dixon in turn sent the copy to the poet and sculptor William Bell Scott, who tracked down more copies and sent one to William Michael Rossetti. Rossetti became one of Whitman's most outspoken backers in England and would go on to publish an influential London edition of Whitman's poems in 1868.84

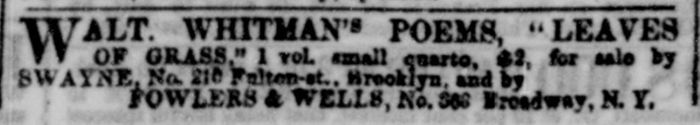

The first known advertisement for the book appeared in the June 29 issue of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.85 An early advertisement in the New York Daily Tribune on July 6, 1855, described the volume as "WALT. WHITMAN'S POEMS, 'LEAVES OF GRASS,' 1 vol. small quarto, $2, for sale by SWAYNE, No. 210 Fulton-st., Brooklyn, and by FOWLERS & WELLS, No. 308 Broadway, N.Y."86

Figure.

Advertisement in New York Daily Tribune, 6 July 1855.

William Swayne, a bookseller, was removed from advertisements shortly thereafter (Allen, Solitary Singer, 149; Greenspan, 91). The price of the book also dropped. In September and October 1855, single copies were advertised in the Tribune for sale for $1, and in November paper copies were listed for sale at 75¢.87 The book was advertised in the London Publisher's Circular and Booksellers' Record of British and Foreign Literature on October 15, 1855 for 6s. 6d. (6 shillings, sixpence).88 Stern writes that Fowler & Wells continued to advertise the book until March 1856, despite lackluster sales, though no ads appeared in the Tribune from November 24, 1855, until February 18, 1856. An ad in the February 18 issue that ran until early March read: "WALT. WHITMAN'S POEMS.—'LEAVES OF GRASS,'—This work was not stereotyped; a few copies only remain for sale, after which it will be out of print."89

Figure.

Advertisement in New York Daily Tribune, 6 July 1855.

William Swayne, a bookseller, was removed from advertisements shortly thereafter (Allen, Solitary Singer, 149; Greenspan, 91). The price of the book also dropped. In September and October 1855, single copies were advertised in the Tribune for sale for $1, and in November paper copies were listed for sale at 75¢.87 The book was advertised in the London Publisher's Circular and Booksellers' Record of British and Foreign Literature on October 15, 1855 for 6s. 6d. (6 shillings, sixpence).88 Stern writes that Fowler & Wells continued to advertise the book until March 1856, despite lackluster sales, though no ads appeared in the Tribune from November 24, 1855, until February 18, 1856. An ad in the February 18 issue that ran until early March read: "WALT. WHITMAN'S POEMS.—'LEAVES OF GRASS,'—This work was not stereotyped; a few copies only remain for sale, after which it will be out of print."89

The first edition of Leaves of Grass met with a great deal of criticism, but several reviewers spoke with admiration of Whitman's style, his imagery, or his use of language. Allen, attributing to Whitman's journalistic network the surprising amount of attention this privately published volume received by reviewers, writes that "Nearly everyone saw in it the influence of Emerson or transcendentalism, or both."90 Reputed admirers would range from Conway, who had read Leaves of Grass at Emerson's encouragement, to Abraham Lincoln.91

VI. Emerson's letter and the reviews and extracts

One of the notable early admirers of Leaves of Grass was Ralph Waldo Emerson himself. In October 1855, some three months after receiving Emerson's laudatory letter, Whitman worked with Charles Dana, then managing editor of the New York Tribune, to print the letter in that paper.92 Whitman also at some point evidently decided to arrange for the independent printing of slips with Emerson's letter with the words "Copy for the convenience of private reading only" at the top. The Tribune clipping or one of the printed slips is pasted into several surviving copies of the 1855 Leaves of Grass. Allen has noted that the newspaper clipping or the printed slip with the Emerson letter may have been purposefully pasted into copies sent to noted authors and journals: examples include Longfellow, whose copy is now at Harvard University.93 The note at the top of the printed slip has been marked through in pencil in several of the copies; in at least one, it has been cut off entirely.94

Whitman also arranged for the printing of an eight-page insertion of reviews and extracts from reviews and critical essays, which was bound into several copies of the 1855 Leaves. Three of the reviews he had written himself and published anonymously in periodicals.95 One extract was taken from an 1844 North American Review article, credited to E. P. Whipple, reviewing Rufus W. Griswold's Poets and Poetry of America—the same Griswold whose unsigned November 1855 review excoriated Leaves of Grass as a "mass of stupid filth."96 Remarkably, Whitman also included Griswold's review in the insertion.97 Another excerpted essay, credited to the London Eclectic Review, was originally a review of Sydney Yendys's The Roman: A Dramatic Poem.98 A brief final paragraph in the insertion, printed with another excerpt under the heading "Extracts from Letters and Reviews," was part of a longer spiritualist essay about life after death.99

The reviews and extracts insertion was probably printed after Griswold's review appeared on November 10, 1855.100 It must have been completed by January 1856, when the last set of cloth bindings were done.101 As Eric Conrad has pointed out, this reviews insertion "clearly anticipated the pre-planned 'Leaves-Dropping' annex of the 1856 edition."102 Several of the reviews also were included in the 1860 pamphlet Leaves of Grass Imprints, produced and promoted by Thayer and Eldridge, publishers of the 1860 Leaves of Grass.103 One brief extract, included in the 1855 insertion under the "Extracts from Letters and Reviews" heading, was taken from a Christian Spiritualist review, from which Whitman would publish longer excerpts in both the 1856 Leaves of Grass and Imprints (1860).104

For the reviews Whitman wrote, comparing the versions bound into the 1855 Leaves with their original published versions in periodicals reveals some interesting differences. Some of these reflect the same kind of close attention to the representation of the physical body of the author evidenced in the alterations to the frontispiece engraving. To Whitman's "Walt Whitman, A Brooklyn Boy," for instance, was added a footnote that had not appeared in the original version of the review when it was published in the September 18, 1855, issue of the Brooklyn Daily Times. The footnote was the catalog of "Phrenological Notes" about Whitman that had been given to him by Fowler in 1849. The notes brought into the review of Whitman's works a distinctly physical vision of the poet, much like the frontispiece had. "This man has a grand physical constitution," the notes read: "He is undoubtedly descended from the soundest and hardiest stock." "[M]arkedly among his combinations" are listed "the dangerous faults of Indolence" and "a certain reckless swing of animal will, too unmindful, probably, of the convictions of others."

Between the periodical and 1855 insertion versions of this review, too, Whitman or a printer shaved off five pounds from the author: the Brooklyn Daily Times version reads "weight a hundred and eighty-five pounds," while the insertion version reads "weight a hundred and eighty pounds."105 By the 1856 "Leaves-Droppings" and Imprints, the review had dropped the mention of weight altogether, although the age was kept, freezing the author in time if not in space: "age thirty-six years, (1855)."106 Perhaps this was because the physical description of the poet had moved into the poetry, necessitating a separation from markers of time and age. The author in the 1855 review, "Of pure American breed, of reckless health, his body perfect, free from taint from top to toe, free forever from headache and dyspepsia, full-blooded, six feet high, a good feeder . . . . ample limbed, weight a hundred and eighty pounds, age thirty six years (1855)" appeared now in "Broad-Axe Poem" (1856) as the last of several representative American figures: "Of pure American breed, of reckless health, his body perfect, free from taint from top to toe, free forever from headache and dyspepsia, clean-breathed, / Ample-limbed, a good feeder, weight a hundred and eighty pounds, full-blooded, six feet high, forty inches round the breast and back."107

Users of the variorum will no doubt notice other significant changes between the original periodical and the 1855 insertion versions of the reviews. To facilitate analysis, we have provided links (using the Juxta collation platform) to comparison views of the three reviews that Whitman wrote, highlighting differences between the periodical versions and the 1855 versions. We have only included links to Juxta comparisons for the reviews written by Whitman for two reasons. First, it is unclear which original periodical version Whitman was working from for some of the reviews and essays he did not write. In the case of the London Eclectic Review article, for instance, Whitman included that source note even though he almost certainly was reading the Harper's Magazine version (which includes a title that matches the one used in the 1855 insertion). Second, when we were able to compare the original version of a non-Whitman-authored review to the version that appears in the 1855 insertion, alterations were minimal. Mostly these consist of minor changes to punctuation or the omission of quoted passages. Notable differences include the considerable and sometimes unmarked omissions from Whipple's essay (the sections Whitman included represent a small proportion of that essay) and the London Eclectic Review essay, as well as, perhaps, a revision from "gross obscenity" to "obscenity" in the second to last paragraph of Griswold's review.108

Some surviving copies of the 1855 Leaves of Grass also include a proof stage of one or more of the reviews Whitman wrote. At least two proof sheets also exist of the extracts from a September 1855 Putnam's Monthly review, unsigned in the original but written by Charles Eliot Norton, which Whitman included in the insertion.109 In the case of the Whitman-authored reviews, these sheets, typically laid into the front or back of copies, feature some differences from both the periodical and the final, eight-page 1855 insertion versions of the text.110 Because there are few substantive differences that are unique to the proofs, which is to say that appear neither in the periodical versions nor in the eight-page insertion versions, we have not treated these proofs separately in the variorum.111 It is worth noting, however, that the proof of "Walt Whitman, A Brooklyn Boy" does not yet include the phrenological note by Fowler, suggesting that the note was a comparatively late-stage addition.

If language from the reviews made it into Whitman's poems in later editions of Leaves of Grass, as in the case of "Broad-Axe Poem," the language of the 1855 Leaves of Grass was also used in the reviews. Several of the reviews Whitman wrote include language quoted and in some cases adapted from the preface and the poems. We have not attempted to note these related passages and quotations in the variorum, other than retaining the original layout when the poetic lines cited in the reviews are set off from the surrounding text as quotations. In particular, the section of the preface that is included in the review titled "Walt Whitman and his Poems"—beginning "the essences of American things" and continuing to the end of that paragraph—is not marked as quoted text, and it features some substantive revisions from (or, perhaps, toward) the text of the preface.112

VII. Copies and later histories

In an 1888 conversation with Whitman, Traubel asked: "So you do not know what became of the first edition?" "It is a mystery," the poet responded, "the books scattered, somehow, somewhere, God knows, to the four corners of the earth: I only know that they never have been in my possession."113 As the century wore on and Whitman's popularity increased, the first edition became both expensive and difficult to find.114 In his 1871 volume Notes on Walt Whitman, John Burroughs concluded his account of the publication and sale of the first edition with the note that "At the present day, a curious person poring over the second-hand book-stalls in side places of northern cities, may light upon a copy of this quarto, for which the stall-keeper will ask him, at least, treble its first price" (19). Burroughs was in earnest, it would seem. An 1877 Boston bill of sale inserted in a copy of Leaves now held in a private collection reported the cost of the transaction as $5.115 And a century and a half later, that price would have been a steal, even accounting for inflation. As of January 2018, seven copies of the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass were offered for sale on AbeBooks.com with listed prices ranging from $45,000 to $270,000.

The books that make up the first edition, different from one another even at the point of production, have become more so over time as the result of use. A series of owners over the course of the ensuing one hundred and fifty years annotated or hand-corrected the copies, pasted bookplates into them, inserted other materials into them, gave them to friends or family members, and in at least one case used them for a purpose quite unrelated to the content of the volume. The Whitman Archive's bibliography of copies, generated and updated from Folsom's 2005 census data and linked from the variorum, provides descriptions and known provenance information for approximately two hundred surviving copies of the 1855 Leaves of Grass now in public and private collections around the world.

The annotations in the surviving copies of the 1855 Leaves suggest a range of responses to the book, covering a long history of reading. A penciled annotation in one copy responds sarcastically to the following lines with the word "modest?":

Divine am I inside and out, and I make holy whatever I touch or am

touched from;

The scent of these arm-pits is aroma finer than prayer,

This head is more than churches or bibles or creeds.

Many other copies have markings next to particular lines. Richard Maurice Bucke marked a typo in a copy given to him by Whitman in October 1890, joining several other readers who noted the same error.116 Owners pasted in bookplates and letters, signed their names on the flyleaves, and occasionally wrote notes about the provenance of the books.117 Whitman himself autographed and dated several copies. Bucke's copy, for instance, is signed by Whitman on the title page.118 Archivists' and booksellers' notes and repository stamps also frequently appear on the endpapers and flyleaves of the books.

If some of the annotations situate the books within a narrative of provenance, others situate them within a broader context of reception. One lengthy series of notes written on the front endpaper of one Library of Congress copy concocts a (mostly false) reception narrative. In pencil is written: "Emerson was asked his opinion of this book—'What a pity,' he said 'that a man with the brain of a God should have the snout[?] of a hog'—Wendell Phillips turned over page after page & said—Here are all sorts of leaves except fig-leaves!" A second owner, reader, or responder wrote below this note: "If this is true then Wendell Phillips has no regret—but Emerson— —" A printed newspaper extract with an 1887 letter from Alfred Tennyson to Whitman is pasted on the same page.119

Other kinds of material were inserted into the books as well. A copy owned by W. L. Tiffany has the imprint of a pressed leaf on page 81.120 The Library of Congress copy with the invented reception narrative includes a photograph of the English actress Ellen Terry, taken by a London photographer.121 In one copy now at the University of Virginia, a reader inserted a newspaper article about female mill workers stopping their work to watch "the boys of Manayunk" bathing in the Schuylkill. The article was placed in the book next to the segment of "Song of Myself" about the "twenty-ninth bather." The headline reads: "Bathing in River Stopped Running of Mr. Ball's Mill: Operatives So Interested That They All Flocked to the Windows."122

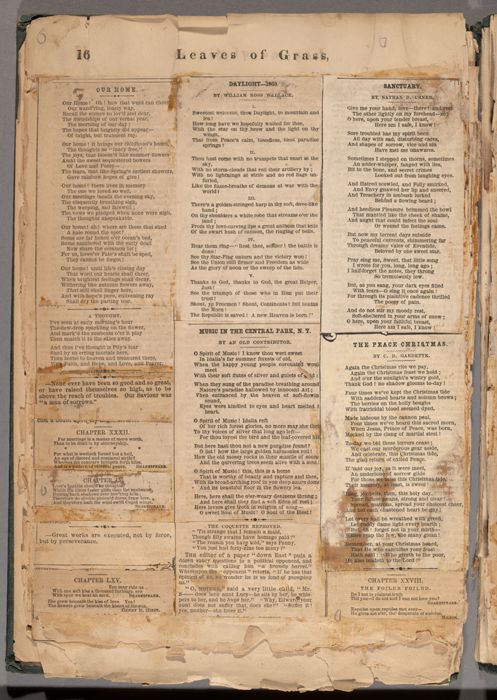

Some owners pasted or inserted other works by Whitman into their copies of the 1855 Leaves. A clipping of Whitman's poem "A Death-Sonnet for Custer" is pasted on the front endpaper of the University of Iowa copy used as the base text for the variorum. A copy of Whitman's "Bardic Symbols," published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1860, was tipped into a copy of the 1855 Leaves now held at Williams College.123 In an extreme example, an owner of one of the copies now held at the Huntington Library took advantage of the unusual size of the book and turned it into a scrapbook, cutting out pages and pasting over the rest with non-Whitman-related poetry and articles clipped from newspapers.

Figure.

A page from a copy of the 1855 Leaves of Grass (HL_01) that was converted into a scrapbook. Image courtesy the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

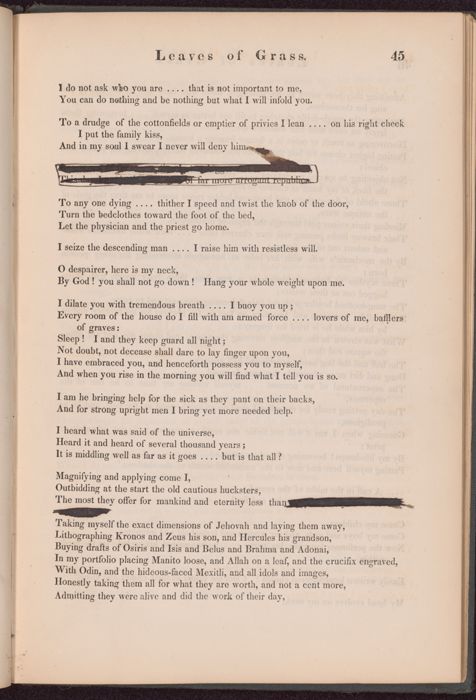

And the copies reflect other reactions of readers to the poetry, including some of Whitman's more controversial lines. One copy at Texas Tech University shows the results of the reader expurgating juicy passages with a pen.

Figure.

A page from a copy of the 1855 Leaves of Grass (HL_01) that was converted into a scrapbook. Image courtesy the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

And the copies reflect other reactions of readers to the poetry, including some of Whitman's more controversial lines. One copy at Texas Tech University shows the results of the reader expurgating juicy passages with a pen.

Figure.

Page of a copy of the 1855 Leaves of Grass (TTU_01) showing a reader's expurgations. Texas Tech University.

Figure.

Page of a copy of the 1855 Leaves of Grass (TTU_01) showing a reader's expurgations. Texas Tech University.

At least one partial copy of the 1855 Leaves has circulated piecemeal. Individual leaves of a "leaf copy" were bound and sold separately by Bennett Book Company in 1930. Printed on the title page included with each leaf are the words: "One precious leaf from the first edition / Leaves of Grass / by Walt Whitman / Who assisted in Setting the Type, Supervised the Press Work, and Lent a Hand in Binding This Book of His Life. / Privately Arranged for 47 Lovers of Whitman / New York, 1930."124

VIII. Variorum edition