Introduction to Whitman's Annotations and Marginalia

Key

| Textual Feature | Appearance |

|---|---|

| Whitman's hand | blue double overline and underline |

| Highlighting | yellow background with top and bottom border |

| Paste-on | gray box with black borders |

| Laid in | white box with black borders |

| Erasure | white text with dark gray background |

| Overwritten | brown with strikethrough |

INTRODUCTION

Walt Whitman's manuscript annotations—hundreds of documents written and drawn upon by America's most famous poet—show the process by which he came into writerly being. They are also fascinating witnesses of nineteenth-century reading practices, and thought-provoking in their own right. In his poetry, Whitman famously depicts himself as a "rough," whose poetry is an organic expression of the American land and way of life. Yet his annotations reveal that from classical rhetoric to the poetry of Tennyson, from Persian mysticism to nineteenth-century phrenological journals, the influences on Whitman's work were historically deep and culturally diverse. With the ongoing publication at the Walt Whitman Archive of Whitman's annotations, widespread access is for the first time possible to anyone wishing to explore the fertile ground of Whitman's self-education, through his reactions to the literature, history, science, theology, and art of his time. Whitman's responses range from the caustic to the puzzled to the awestruck, and they take the form of everything from simple underlining of significant passages to full-length critical expositions. Much guesswork and close reading has been done with Whitman's work to assert its origins or its debt to the literary environment: these documents offer concrete links between inspiration and creation, and will challenge a range of assumptions about Whitman and the relations among American literature and cultural and intellectual history. Indeed, Whitman's very compositional technique derived in part from his annotational habits. This introduction to Whitman's annotations and marginalia will describe the body of materials treated under those labels here at the Whitman Archive, offer some of the history of their previous publication, and, using a few examples, sketch their significance. Technical information is included at the end of the introduction, including a list of funders, library partners, and the advisory board from the initial grant-supported period.

ANNOTATIONS AND MARGINALIA

Defining any genre within Whitman's work is tricky, since the poet made a habit of hybridizing different literary forms for most of his career—breaking boundaries was his style. There are thousands of documents extant on which Whitman wrote, for example, no more than a simple identifying citation (as in the case of hundreds of newspaper clippings, held in archives across the United States). In certain cases, meaning is conveyed without marks at all, such as when Whitman aggregates a number of newspaper clippings that are clearly related (which he did for Civil War regiments and for pieces on labor strikes and tramps). Whitman often annotated his own writings or writings about him. And there are a host of documents in which Whitman muses on a previous author, but that we know to be drafts of later-published work or lectures. For the purposes of this section of the Whitman Archive, we have emphasized pieces that are not obviously drafts of published poems or prose works. We have focused on Whitman's notes that comment on other writers' works (rather than his own), whether "annotations" (standalone notes entirely in manuscript that make reference to an identifiable external work, performance, or conversation) or "marginalia" (manuscript notes that Whitman made directly on a printed version of an original text such as a book or clipping from a periodical).

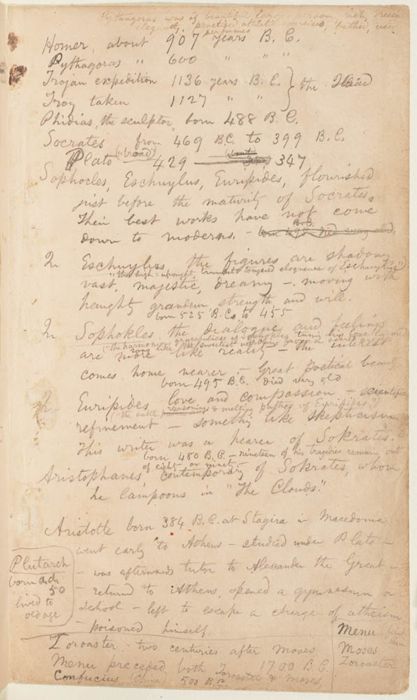

Whitman's marginalia reveal crucial links between his social context and his published writing. The origins of some of his most famous poems, for example, may be found recorded in the margins of his reading in nineteenth-century books and periodicals. Finding such connections can bring startling new interpretations to bear on Whitman's poetry and suggest useful methods for research into other nineteenth-century authors' works. Take Leaves of Grass: Matt Miller has shown that when we turn to Whitman's annotations, we discover a different chronicity to the composition of the first edition of Leaves than has been assumed. Rather than composing his famous 1855 text largely from scratch beginning in a mystical inspiration starting in late 1853, the poet transformed notes he had taken earlier (on a range of texts and about American literary style) into long poetic lines. An annotation on Greek intellectuals in the collections at Duke University offers an example (fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Whitman's notes on Greek intellectuals. Trent Collection of Whitmaniana, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, MS 4to 86; Frey III:26.

While annotations such as this may not appear to be poetry, Miller points out that not only do they often feature content that ends up in his poems, but with its hanging indentation and topical fragmentation, Whitman's annotational style "looks like his signature line" (Miller 27). The major archives of Whitman documents contain over 1000 such documents, some many pages long, many previously uncollected and unpublished.

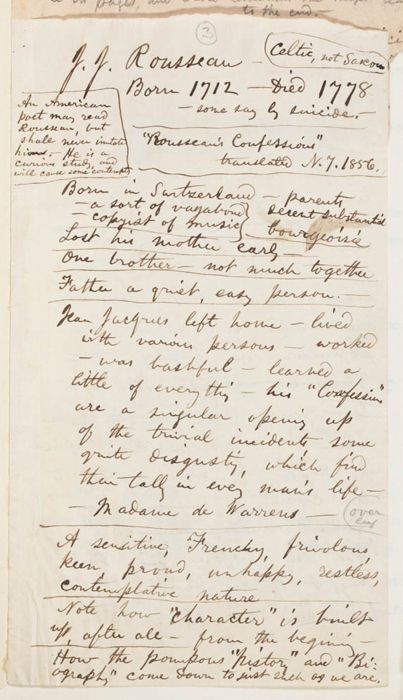

More fundamentally, Miller's work suggests that Whitman's compositional method relied upon annotations no less than on poetic transformation. Whether writing poetry or prose, the poet turned to the notes he had taken—during reading, or following a conversation or performance, or from his imagination—when it came time to generate his work. Thus Whitman's annotations are the root of much of his published work and key to understanding not just the sources and the chronology, but the very form of both his poetry and prose. Indeed, it is possible to see in some annotations the layering of literary theory, content, and practice. In another document from the Duke holdings, Whitman engages with Jean-Jacques Rousseau, taking detailed notes on the French writer that shed light on Whitman's relation to continental literature and philosophy (fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Whitman's notes on Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Trent Collection of Whitmaniana, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, MS 79; Frey III:14.

The poet makes both notes and a meta-note about how to handle figures like Rousseau: "An American poet may read Rousseau," Whitman notes in a box at the top left, "but shall never imitate him.—He is a curious study, and will cause some contempt."

The nationalism of that comment notwithstanding, the annotations speak eloquently to the recent surge in scholarly understanding of the transnational dimensions of nineteenth-century American literature. Whitman's "Prayer of Columbus," for example, seems to have been inspired by his reading of an article in the Irish Republic (LOC card 720; Detroit Catalog no. 32). It has long been asserted, too, often based largely on internal textual evidence, that Whitman was influenced by middle eastern spiritual writing; the Middlebury collection contains a fascinating set of annotations on Persian poetry that confirms and complicates that assertion, and that will do much to animate the story of American literature, in Wai Chee Dimock's formulation, "through other continents." Kenneth Price's Whitman and Tradition and Floyd Stovall's The Foreground of Leaves of Grass both showed Whitman's complex relationship to European literature and criticism by exploring his marginalia, but this critical methodological emphasis remains rare.

We also learn much about the poet's life from his annotations as a corpus. Having never attended college, Whitman's reading and his conversations with people, together with his visits to the theatre and opera, were his education. If these documents, then, offer insight into the self-educative possibilities of urban nineteenth-century America (during a period of excitement about public libraries, as Thomas Augst has shown), they also suggest how Whitman created himself both as a prose writer and editor—and then how he transformed himself into a poet. Stovall used Whitman's marginalia to argue, for example, that the poet's shift in reading from American journals in 1845-47 to British journals in 1848-49 tells us that Whitman was educating himself to become a poet in those latter years, reading literary criticism and accounts of the lives of poets (Stovall 143-152; see also Klammer 71-3).

Perhaps because Whitman's methods of writing drew upon the form and content of his annotations and marginal notes, he preserved much of this material until the end of his life. Thanks to the fastidiousness (and bibliophilia) of his literary executors and friends, a large corpus of these kinds of texts survives. Yet the scholars cited above almost exhaust the list of those who have engaged Whitman's annotations in depth, largely because the materials are held in archives across the United States, are difficult to understand without the larger context of similar documents, and have seen only limited publication.

This isn't an uncommon literary-historical situation. In the broader field of literary studies, there are few projects that gather and display an author's marginalia. Annotations made by writers in the margins of printed texts or images are crucial sources for analysis in literary, philosophical, and historical study because they are rare evidence of a reader reacting directly to his or her influences. Marginalia also demonstrate the range of such influences, which often reach far beyond the genres in which the annotator worked. In a famous marginal note, Whitman wrote that "all kinds of light reading, novels, newspapers, gossip, etc, serve as manure for the few great productions." While there has been a resurgence of interest in marginalia in popular media, and while a small number of influential scholarly studies in literature, history, and bibliography have emerged from the archival study of marginalia, such study has not penetrated the methodologies of the humanities or social sciences because collections of annotations are available for only a few writers, such as Herman Melville and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and statesmen such as John Adams.

Print editions, even simple transcriptions, of documents that combine printed text, marginalia, and images, are expensive; this cost may partly explain the paucity of published annotations collections. But even among digital archives, initiatives to preserve annotations by nineteenth-century figures are still rare. There is no collected publication of Whitman's extensive body of marginalia. With the exception of the Whitman marginalia folders held at the Library of Congress, notes and annotations are combined in archives, meaning that a researcher has to sift through the entirety of these collections (no small task) to find the marginalia. Whitman took notes in books as well as in magazines and newspapers, and these are often found in separate collections. Some annotations can only be found in unlikely and undercatalogued places; in oversize folders, correspondence, ephemera, or collectors' specially bound volumes of Whitman objects or nineteenth-century literary ephemera.

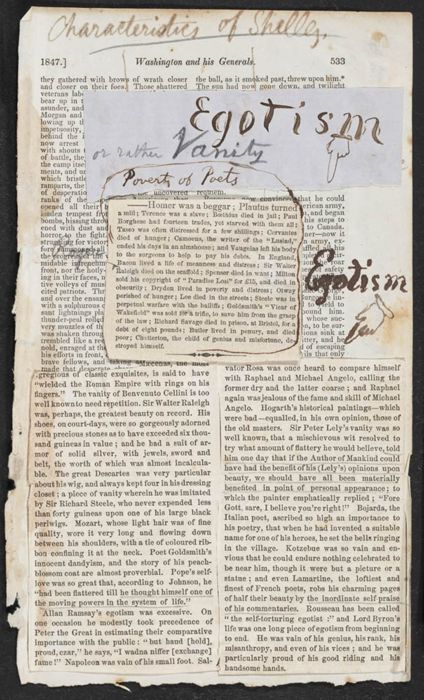

Digital presentation of annotated documents has much to offer, but in practice it is difficult to effect. Annotations, after all, are their own form of text markup, a re-presentation or re-framing of an original text. They depend on more than their linguistic content to make meaning; it makes a difference where on the page a comment is made. The significance of spatiality in relating layers of information pushes markup like ours, based on the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) standards, to and perhaps beyond its descriptive limits. Take, for example, one of Whitman's annotations on a collection of periodical pages he cut out and assembled on top of an 1847 article on George Washington (fig. 3):

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

"Characteristics of Shelley," some of Whitman's notes on egotism. Trent Collection of Whitmaniana, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, MS 4to 75; Frey III:7.

Represented here in about a three-inch-square space are challenges to several levels of scholarly digital editing—analytical, historical, technical, and bibliographical. First, if we think of annotations as a kind of old-fashioned "tagging," this document exemplifies the difficulties of capturing metadata with more metadata—the theme of Whitman's markup here is the relationship between poets and their predecessors or between poets and their own reputations. "Like the printer he had once been and the maker of books he would soon be," Ezra Greenspan wrote of the young Whitman, "he went through texts, as it were, with scissors in one hand, pen in the other" (74). Whitman has manipulated the physical properties of the elements of the collage in order to relate texts without necessarily unifying them. So the precise relationships of one paste-on to others, and to the commentary written on them or between them, are essential to how the document makes meaning. TEI-based XML makes it simple to mark sections that have been underlined or otherwise grouped by a reader on a single piece of text. But the section here labeled "Poverty of Poets" by Whitman embraces three different pieces of paper, and presumably includes the marginal note "Roger" he has added to indicate which Bacon the text refers to—a note written in the margin relative to the annotated text, but not in a margin relative to the whole document. That he has written over the underlying document in making that note suggests that we might treat the underlying article as insignificant, as "background" relative to encoding the "Poverty of Poets" section that covers it. But can we be absolutely certain that Whitman did not intend to let the words "uncovered" and "requiem" peek through here? And even if Occam's razor suggests Whitman's penknife merely cut too close by chance, revealing those words, it has seemed important to us to allow as many of these kinds of features as possible to appear in our versions, in order to facilitate richer or more robust interpretations. To this end, we have transcribed and tagged all textual content of documents that Whitman marked, including content added by libraries, archives, collectors, or other handlers.

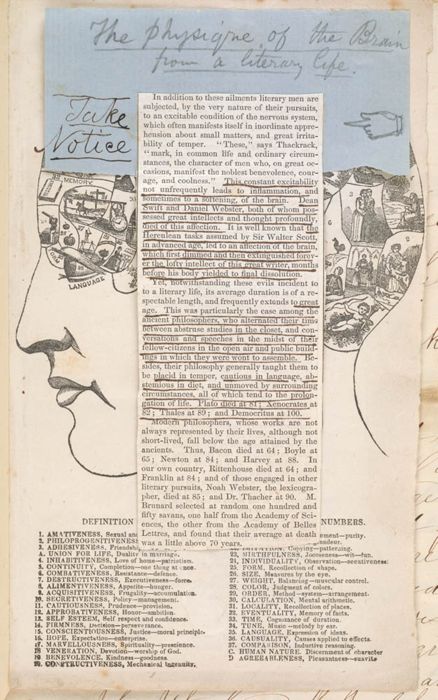

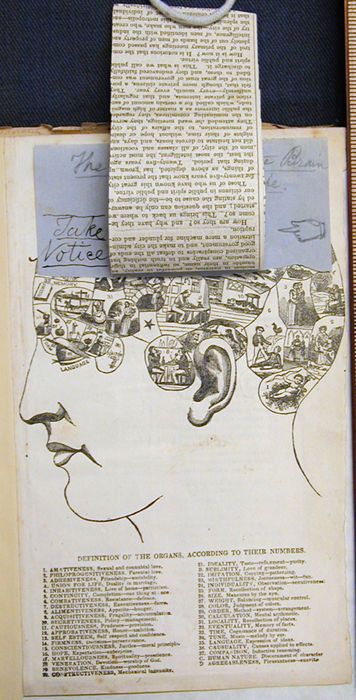

Whitman annotated images as well as printed texts; take, for example, his notes on a phrenological chart (fig. 4):

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

"The physique of the Brain," some of Whitman's notes on phrenology. Trent Collection of Whitmaniana, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, MS 4to 148; Frey p. 66, item 24.

The issues represented in figure three are complicated here not only by the presence of an image in the hierarchy of meaning, but by the fact that the front clipping is pasted on only at its top: Whitman has positioned it so that it can be lifted and the emblematic map of the human brain underneath accessed (fig. 5):

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

"The physique of the Brain," with pasteon flap lifted.

Our interface design, then, makes images and text transcriptions of each of these collage components available, highlighting text written by Whitman, to facilitate the reading of documents that depend upon the physical qualities of paper and arrangement no less than on words.

Annotations give virtually irrefutable evidence of a writer having read a text. For historians and literary critics, knowing whether or not a writer read a particular work is of tremendous value, but it is often difficult to prove, given the scattering of documents and the heterogeneity of archival finding aids. With this in mind, we are slowly building a searchable database of Whitman's reading. Whitman's library was a constantly shifting entity during his life, as the poet shared books, periodicals, and letters with his friends and they in turn frequently gave or loaned him texts. The database features basic bibliographic information about each text Whitman read, a brief description of his reaction (if known), and a "source" field describing the evidence for the assertion that Whitman read a particular text.

PREVIOUS EDITIONS OF WHITMAN'S ANNOTATIONS

Previous substantial publications of Whitman's annotations may be found in The Complete Writings (volumes 6 and 7), edited by Whitman's literary executors (a republication of Richard Maurice Bucke's Notes and Fragments of 1899); Edward Grier's Notebooks and Unpublished Prose Manuscripts (1961-1984; volumes 5 and 6); and in Joel Myerson's three-volume edition titled The Walt Whitman Archive (1993). Others are scattered in a range of publications, including for example Horace Traubel's With Walt Whitman in Camden (1902-1999) and Thomas Donaldson's Walt Whitman the Man (1896), as well as a number of auction catalogs. The Complete Writings features transcriptions of many Whitman annotations, but no facsimiles and little or out-of-date information about the location of documents. In many cases, too, these notes exclude marginalia; where marginalia are transcribed, the source text is sometimes named but seldom transcribed. Given the widespread reprinting characteristic of periodical publication during Whitman's time, precise bibliographic information about the source of a text the poet read and annotated has historically been difficult to derive, but with the help of digitized periodical databases we have been able to specify or disambiguate many sources for clippings and extracts. Grier's work expands on and overlaps with Bucke's volume, but is likewise incomplete; it contains, however, detailed headnotes that we have at times drawn on for our metadata. Myerson's edition contains facsimiles from the Duke University and Harry Ransom Center collections, but it focuses on the poetry manuscripts and notes, not on annotations—his edition includes only three documents that we preserve here (2:654-55). Several articles and bibliographies, including a list of newspaper and periodical clippings owned by Whitman from The Complete Writings (7:63-97), have guided us in our development of the list of documents to be digitized; see below for a comprehensive list.

TRANSCRIPTION, ENCODING, IMAGING

We have used the current Whitman Archive encoding guidelines to encode our transcriptions in TEI-compliant XML markup. This includes standard MARC metadata about each object, as well as the assigning of a unique identifier within the Archive (the "WorkID") to each document. We created a small number of extensions to the current Whitman Archive schema in order to capture some of the complex relations between the physical and the intellectual features of the documents in this corpus. While the manuscript encoding captures a range of textual features such as strikeouts, insertions, erasures, and so forth, much of the textual content of the annotations documents is printed text—the original text on which Whitman made comments. While we have tried to include dating information, this often proves difficult to ascertain. As Ezra Greenspan points out, "because of Whitman's customary procedure of reading (and sometimes annotating) [texts] repeatedly over the years, it is not always possible to relate specific readings to specific dates in his life. This limitation notwithstanding, one can discern a general pattern by which he read broadly for his self-education in the last half of the 1840s, then gradually in a more directed fashion as he came to focus on matters more specifically related to poetry and culture" (74). As a result, we have emphasized year ranges over specific dates.

OCR-captured text was used in some cases as the starting point for such documents, but all transcriptions and encodings went through checking and proofing stages subsequent to their initial drafting. Images obtained from our library partners were scanned at 600dpi in tif format. Images obtained at the Library of Congress were shot with a Canon 5D digital SLR camera in RAW format and output to tiff format. All images are archived at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and transcriptions were made from these images. The visual interface was developed principally by Karin Dalziel and Nicole Gray at the UNL Center for Digital Research in the Humanities.

SUPPORT

This project was funded by a National Endowment for the Humanities Digital Humanities Start-Up Grant (HD-50236-07) in 2007–08 (through Duke University), and NEH Preservation and Access Humanities Collections and Reference Resources grants from 2011–2014 (PW-50772-11, University of Texas at Austin) and 2017-2019 (PW-253797-17, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). It has also been supported by the Departments of English at the University of Texas at Austin and at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the Walt Whitman Archive, and the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln

LIBRARY PARTNERS

- The Library of Congress Rare Books Division

- The Library of Congress Manuscripts Division

- Duke University Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Special Collections

- Bryn Mawr University Special Collections

- Rutgers University Special Collections

- Middlebury College Rare Books and Special Collections

- The New York Public Library

- The Beinecke Library at Yale University

- The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Ohio Wesleyan University Special Collections

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following people generously contributed time, care, and effort to the project: at the Library of Congress, Clark Evans, Alice Birney, Eric Frazier, and Mark Dimunation; at Bryn Mawr College, Cheryl Klimaszewski and Melanie Levy; at Rutgers University, Albert King; at Duke University, Will Hansen and Erica Fretwell; at Middlebury College, Andy Wentink; at the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, Raffaelle Viglianti; at the Walt Whitman Archive, co-directors Kenneth Price and Ed Folsom, Ashley Lawson, Brett Barney, Liz Lorang, Karin Dalziel, Jessica Dussault, and Jonathan Cheng; at the University of Texas at Austin, Travis Brown, Elizabeth Cullingford, Sarah Sussman, Mike Speriosu, Laura Beerits, Lauren Trojniar, Cecilia Smith-Morris, Andrea Golden, Donetta Dean, Nathaniel Bilhartz, Elizabeth Frye, Nicole Gray, Lauren Grewe, Ty Alyea, Alejandro Omidsalar, and Ashley Palmer.

ADVISORY BOARD

- Terence Catapano, Digital Production Manager, Mark Twain Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

- Steven Olsen-Smith, Professor of English, Boise State University, and Holland H. Coors Endowed Chair, US Air Force Academy

- William H. Sherman, Head of Research, Victoria & Albert Museum, and Professor of Renaissance Studies, University of York

- Michael Winship, Professor of English, University of Texas

- Heather J. Jackson, Professor of English, University of Toronto (member from 2011–2014)