Tuesday, May 22, 1888.

Tuesday, May 22, 1888.

[See indexical note p191.4] W. handed me a copy of The Journal of Speculative Philosophy. "I shall ask you to take that away and never bring it back," he said, laughing. Why? "There is nothing in it to interest me—nothing. I like Harris—we have met: he is friendly to Leaves of Grass—is rather inclined to accept it—is at least lenient—though I guess I am on the whole not occult enough—not obscure enough—to satisfy the particular brand of philosophy he professes. [See indexical note p191.5] Mind you, I don't say read it—I only say, take it away."

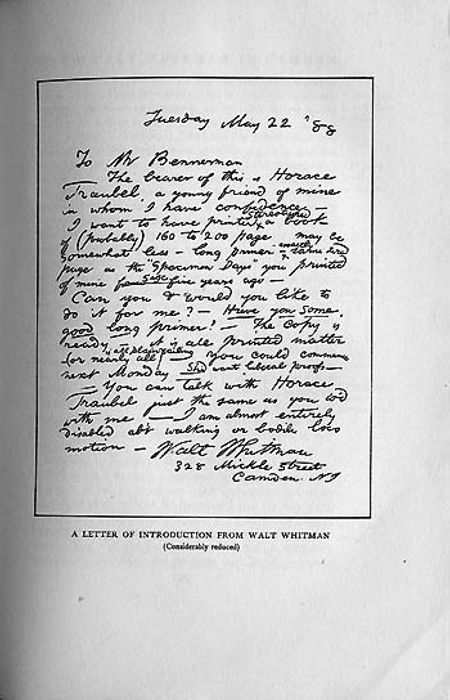

[Begin page 192]Talked about November Boughs, W. showing me the copy and the plans as he had drawn them up. [See indexical note p192.1] "I want you to see Mr. Bennerman—to get all possible information before we set out: if the Sherman people cannot do it we will have to look up somebody else. I have written a letter to Bennerman—letter of inquiry and introduction—both: here it is. I think it covers the case: he will be able to answer us yes or no. Then we will know where we are."

Tuesday, May 22, 1888. To Mr. Bennerman:[See indexical note p192.2] The bearer of this is Horace Traubel, a young friend of mine in whom I have confidence—I want to have printed stereotyped a book of (probably) 160 to 200 pages—maybe somewhat less—long primer—exactly same sized page as the Specimen Days you printed of mine six years ago—

Can you and would you like to do it for me?—Have you some good long primer? The copy is ready—it is all printed matter—(or nearly all)—is all plain sailing—you could commence next Monday—sh'd want liberal proofs—

You can talk with Horace Traubel just the same as you w'd with me—I am almost entirely disabled ab't walking or bodily locomotion—

Walt Whitman.

[See indexical note p192.3]

"What portrait or portraits shall we put into the book?" asked W. "I have wavered between Eakins and Morse: Morse's, on the whole, seems to me best: is better for this purpose—as a distinct portrait. I think we should have the proper photos taken experimentally at once from the bust—or in a week or two. I am a little doubtful about getting the view I desire: I want your man to try and try and try again until the right one is secured. It is like ordering a suit of clothes: I can give the tailor a hint of what I want, but he must lumber out his stock—wait for me to recognize the right piece. I don't believe in the 'great' photographers—

[Begin page figure-15]

[Begin page 193]the swells with reputations—I think the other fellow is just as apt to hit it. [See indexical note p193.1] There is so much in the atmosphere, surroundings—in the whole circumstance. The other fellow is less likely to be a slave to rules."

[Begin page 193]the swells with reputations—I think the other fellow is just as apt to hit it. [See indexical note p193.1] There is so much in the atmosphere, surroundings—in the whole circumstance. The other fellow is less likely to be a slave to rules."

W. alluded to Carlyle as "that terrible fellow—that terrible octopus—who kept forever growling out to us that we were all going wrong here in America—all the democrats—all the radicals: all going after a mistake—a delusion: all, all: going only to come back. [See indexical note p193.2] Well, I am holding myself under restraint: as they say out West, I 'hold my horses': perhaps that best expresses me—radicalism plus philosophy. Tennyson is constantly saying the same things with regard to us—bringing us up against our conceit, perhaps: he seems to have no faith in our democracy. [See indexical note p193.3] My leanings are all towards the radicals: but I am not in any proper sense of the word a révolutionnaire: I am an evolutionist—not in the first place a révolutionnare. I was in early life very bigoted in my anti-slavery, anti-capital-punishment and so on, so on, but I have always had a latent toleration for the people who choose the reactionary course. The labor question was not up then as it is now—perhaps that's the reason I did not embrace it. [See indexical note p193.4] It is getting to be a live question—some day will be the live question—then somebody will have to look out—especially the bodies with big fortunes wrung from the sweat and blood of the poor. This is all so—all of it so. Yet I do not feel as if I belonged to any one party."

Reverting to November Boughs W. said: "I have money enough to see it through: I have some money, but am chary of putting it out, as you know. But I recognize that nothing can be done without it—therefore I pay my way right through, preferring to have it understood so at the start—being rather averse to arranging for my books on any other terms. [See indexical note p193.5] You will see Bennerman. Tell him I want two men put on November Boughs from next Monday—proofs [Begin page 194] sent daily—each evening if possible: this is imperative, for the book must be out by fall. [See indexical note p194.1] As to the manuscript, although it's all ready, I'll leave it mainly in your hands—appoint you sort of supercargo: not giving it all over to the printer at once—giving it to him piece by piece only as he needs it. I have never lost any manuscript with printers but I don't want to run the risk. It's such a hell of a job for me to write now—I mean physically a job—I don't want to have to do any of this work over a second time. Well—you will first see Bennerman: we have to know his pleasure before we can proceed."

[See indexical note p194.2] After a pause W. went on: "I have another errand for you. I do not own the plates of Specimen Days: I ought to, but I don't: they belong to Dave McKay. I want you to go to McKay and make him an offer of one hundred and fifty dollars spot cash for the plates." He laughed and asked: "By the way, what is spot cash?" after my reply adding: "I guessed right, anyway. Offer him the one fifty spot cash. I don't believe Dave will accept the offer—no business man could resist the temptation to put more on an article some one was eager for. [See indexical note p194.3] But try him, anyway. If he says no then I guess it must be no: I don't think I am eager enough for the plates to increase my bid." Again: "I like to supervise the production of my own books: I have suffered a good deal from publishers, printers—especially printers, damn 'em, God bless 'em! The printer has his rod, which has often fallen on me good and powerful."

W. said as I was going: "I am watching your pieces as they appear in the papers and magazines—reading them all: you are on the right tack—you will get somewhere. I don't seem to have any advice to give, except perhaps this: Be natural, be natural, be natural! [See indexical note p194.4] Be a damned fool, be wise if you must (can't help it), be anything—only be natural! Almost any writer who is willing to be himself will amount to something—because we all amount to something, to about [Begin page 195] the same thing, at the roots. The trouble mostly is that writers become writers and cease to be men: writers reflect writers, writers again reflect writers, until the man is worn thin—worn through. I have been interested in your pieces—they are significant. [See indexical note p195.1] You seem to want to be honest with yourself. I'm sure I couldn't think of a better start in anything for anyone." [See indexical note p195.2] And finally: "I guess for one thing you will be our historian: we will have to rely upon you to review the field after the fight is all over. I do not mean a matter of mere biography: I mean the Walt Whitman movement, the Horace Traubel movement, that commenced long before either of us was born—that will go on forever after we are dead."