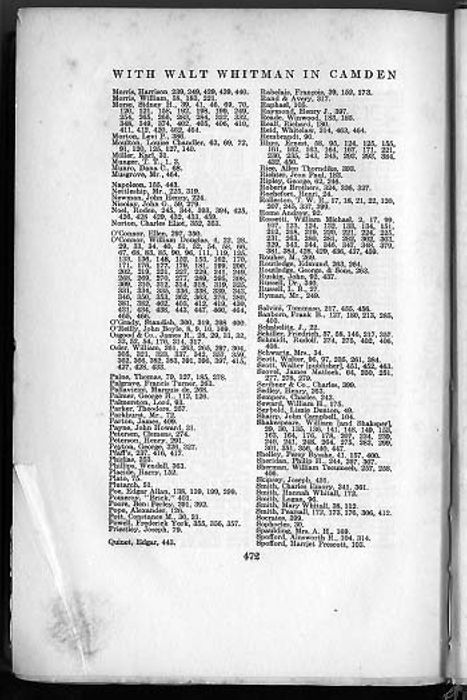

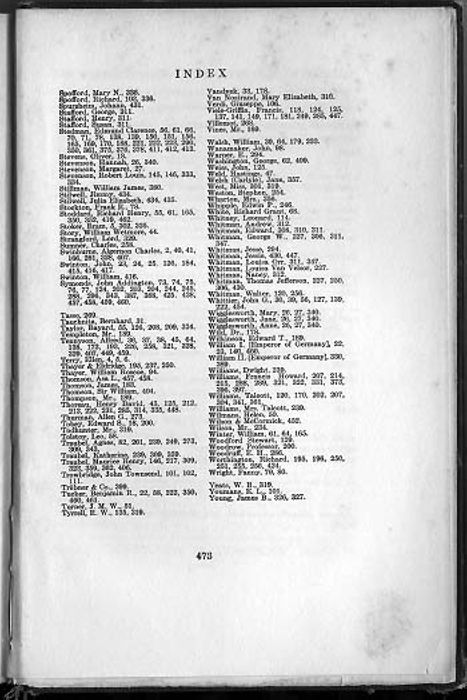

With Walt Whitman in Camden (vol. 1)

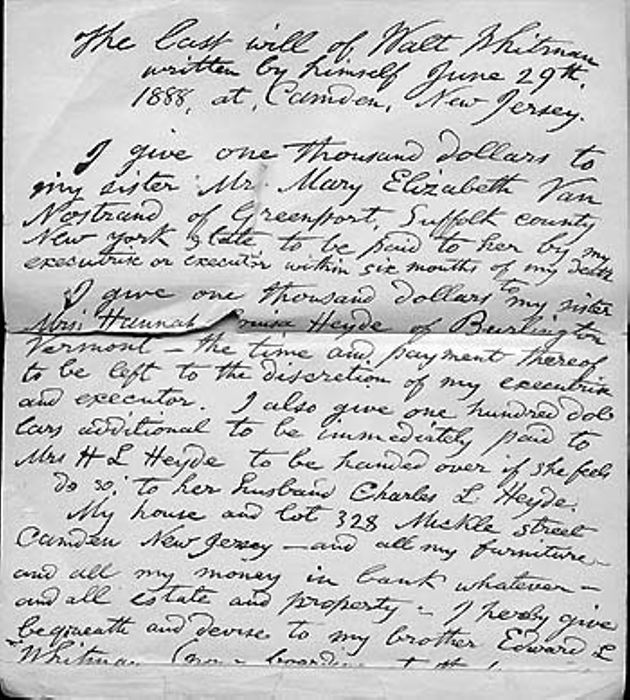

WALT WHITMAN (About 1869)

WALT WHITMAN (About 1869)

Copyright, 1905, 1906, by Horace Traubel

Copyright, 1905, by The Century Company

Entered at Stationers' Hall

Published February, 1906

Press of Geo. H. Ellis Co.

Boston, U.S.A.

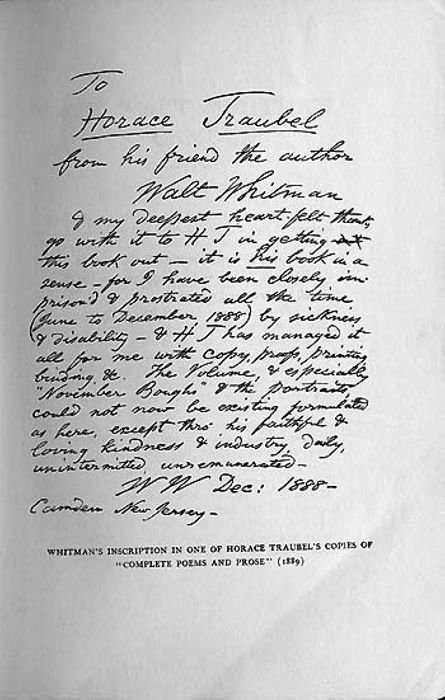

To Readers

My story is left as it was originally written. I have made no attempt to improve it. I have taken nothing off and put nothing on. I know that it has defects. I am not ashamed of defects. I know that it has virtues. I am not proud of virtues. Here is the record as it virginally came from my hands in the quick of the struggle it describes. It might have been made more literary. It might have been made more precise. Its loose joints might have been tightened. Some commas might have been put where colons are. Phrases might have been swung about. The formal grace of the recital might have been improved. I have preferred to respect its integrity. To let it remain untouched by a censorship. To let it continue, for good or bad, in its then native atmosphere. I do not want to reshape those years. I want them left as they were. I keep them forever contemporary. I trust in the spontaneity of their first inspirations.

Did Whitman know I was keeping such a record? No. Yet he knew I would write of our experiences together. Every now and then he charged me with immortal commissions. He would say: "I want you to speak for me when I am dead." On several occasions I read him my reports. They were very satisfactory. "You do the thing just as I should wish it to be done." He always imposed it upon me to tell the truth about him. The worst truth no less than the best truth. He did not ask to have his failings paraded but he did ask that they should not be hid. He knew that imperfection is a part of perfection. He knew that our blood runs black as well as red. He did not like evil talked about as if it was fatal. But he knew that a place must be provided for it in any portrait of a person or in any portrayal of an event. So I have let Whitman alone. I have let him remain the chief figure in his own story. This book is more his book than my book. It talks his words. It reflects his manner. It is the utterance of his faith. That is why I have not fooled with its text. Why I have chosen to leave it in its unpremeditated arrangement of light and shade. Why I have not attempted to make it conform to any arbitrary humors of the bookmaker. It was not my purpose to produce a work to dazzle the scholar but to tell a simple story. Or, rather, in the main, to let a certain story tell itself. I have done nothing negatively to disguise any poverty in the portrait and nothing affirmatively to falsely enrich it. I have had only one anxiety. To set down the record. Then to get out of the way myself. To give the observer every privilege of vision. I do not come to conclusions. I provide that which may lead to conclusions. I provoke conclusions.

A number of the collateral documents quoted are from Whitman himself. These are printed without repair. They are kept to his own text without elision and without change. The same thing may be said of the letters from others to Whitman. Nothing has been done to sophisticate the text. It occurs here in the rude dress natural to the incidents that produced it. I had no time then to polish. I have had no disposition since to do what I had no time to do then. The record begs no questions. Never makes worse of better or better of worse. Tries to explain away no sin. Tries to lug in no virtue. Whitman was not afraid of the man who would make too little of him. He was afraid of the man who would make too much of him. He knew that it was easier to survive some kinds of enemies than to survive some kinds of friends. Whitman did not insist upon his faults. But he wanted them all counted in. The last fault with the first fault. He would rather have been thought too little of than too much of. I have never lost sight of his command of commands: "Whatever you do do not prettify me."

HORACE TRAUBEL Camden, February, 1906ILLUSTRATIONS CONTAINED IN THIS VOLUME

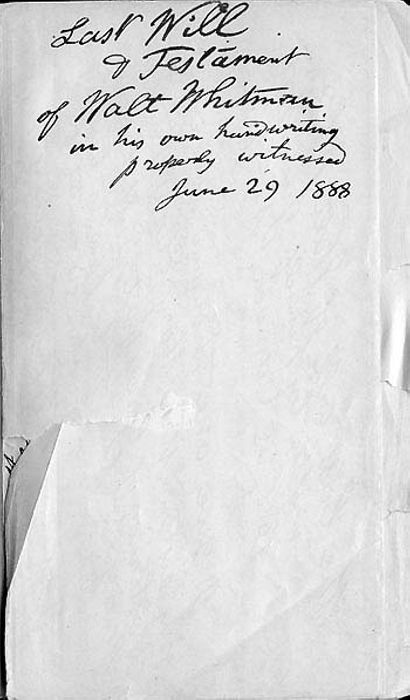

| Last Will and Testament of Walt Whitman, | Facing page ii |

| "In his own handwriting, properly witnessed, | |

| June 29, 1888." | |

| Walt Whitman | Frontispiece |

| From a photograph by Spieler, about 1869 | |

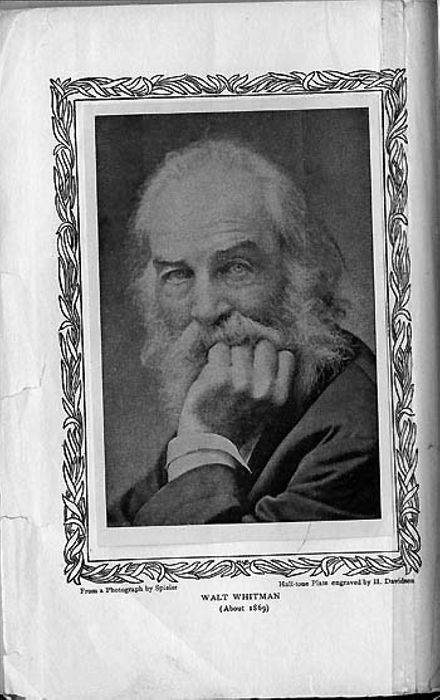

| Whitman's Inscription in one of Horace Traubel's | |

| Copies of "Complete Poems and Prose" (1889) | Page xv |

| Facing Page | |

| William Douglas O'Connor | 4 |

| From a photograph by Merritt & Wood, 1887 | |

| Mickle Street, Camden, New Jersey | 20 |

| Drawn by Harry Fenn, from a photograph by Dr. John Johnston | |

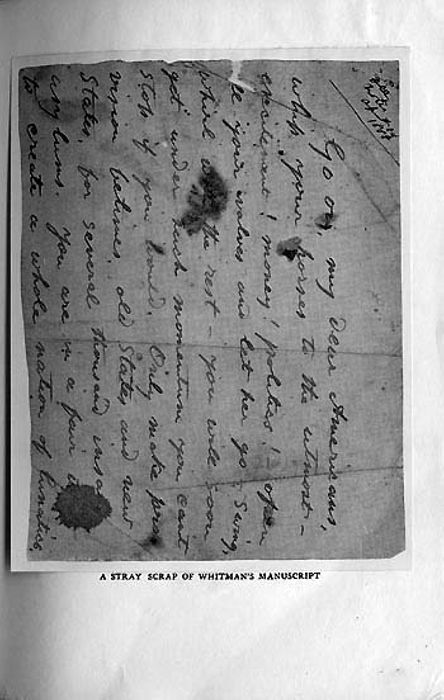

| A Stray Scrap of Whitman's Manuscript | 26 |

| "Go on, my dear Americans" | |

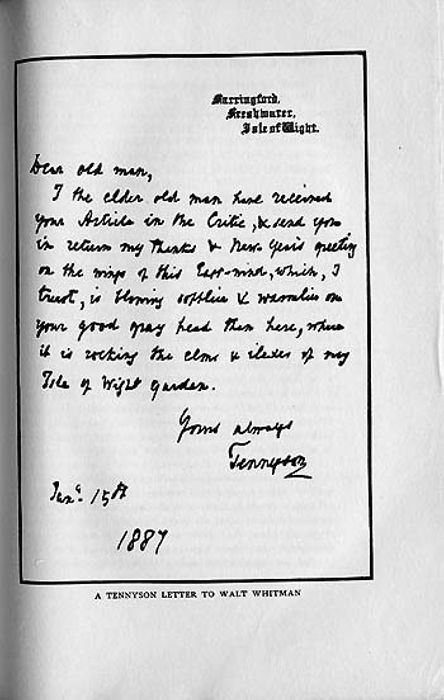

| A Tennyson Letter to Walt Whitman | 36 |

| Robert G. Ingersoll | 38 |

| From a photograph by Houseworth & Co., 1877 | |

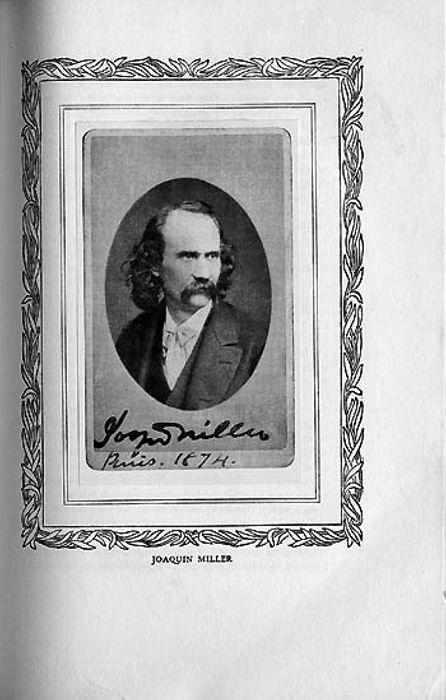

| Joaquin Miller | 44 |

| Paris, 1874 | |

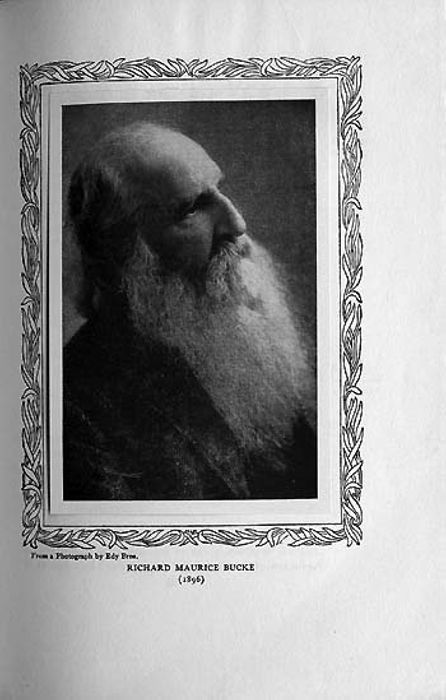

| Richard Maurice Bucke | 66 |

| From a photograph by Edy Bros., 1896 | |

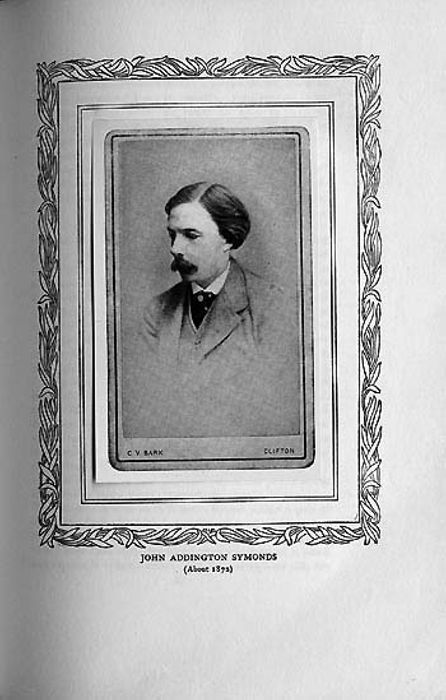

| John Addington Symonds | 76 |

| From a photograph by C. V. Bark, about 1872 | |

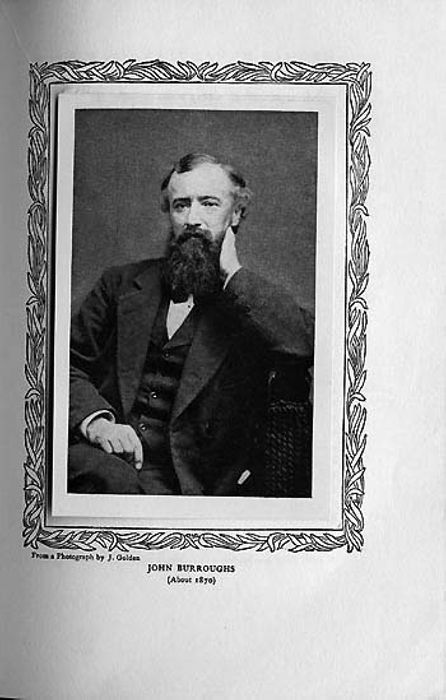

| John Burroughs | 88 |

| From a photograph by J. Golden, about 1870 | |

| Edward Carpenter | 104 |

| About 1879 | |

| Daniel G. Brinton | 128 |

| About 1899 | |

| Walt Whitman | 154 |

| From the painting by Thomas Eakins, 1887 | |

| Richard Watson Gilder | 170 |

| From a photograph by George C. Cox, about 1880 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| Facing Page | |

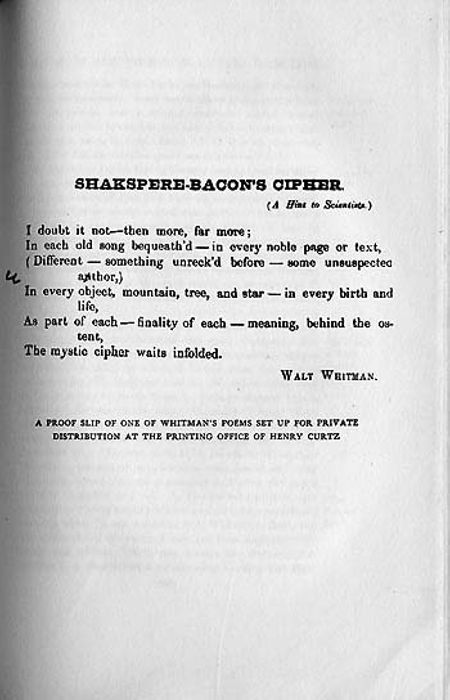

| "Shakespere-Bacon's Cipher" | 180 |

| A proof-slip of one of Whitman's Poems for private distribution | |

| set up at the printing office of Henry Curtz | |

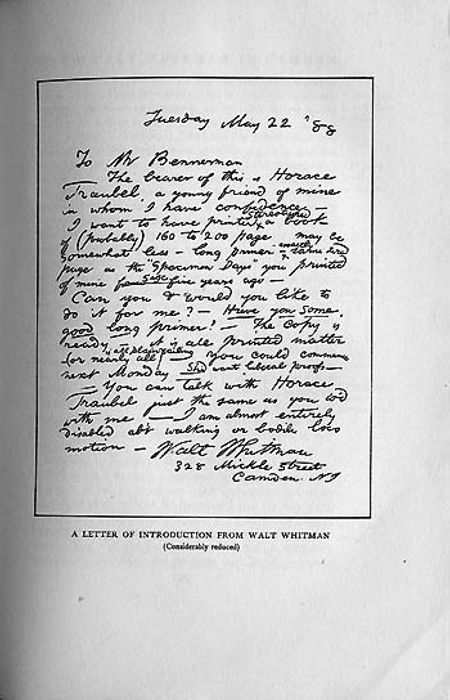

| A Letter of Introduction from Walt Whitman | 192 |

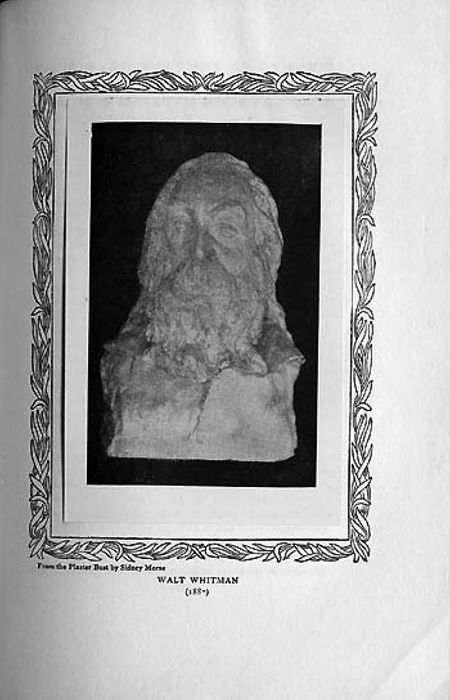

| Walt Whitman | 198 |

| From the plaster bust by Sidney Morse, 1887 | |

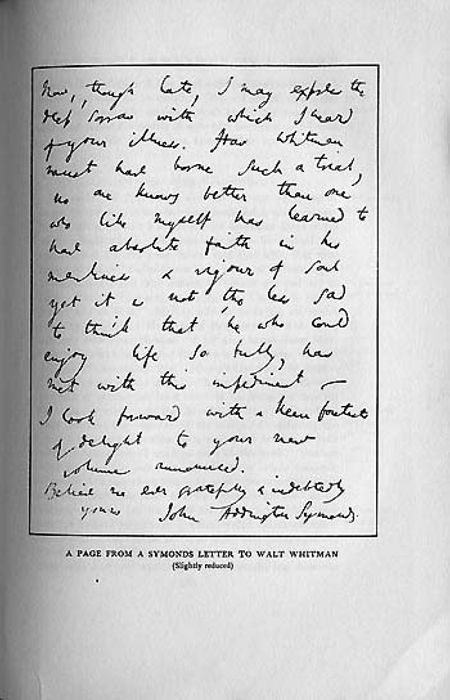

| A Page from the Symonds Letter to Walt Whitman | 204 |

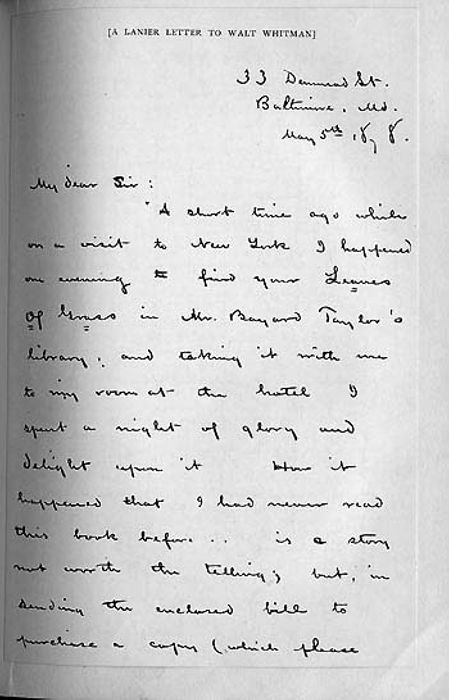

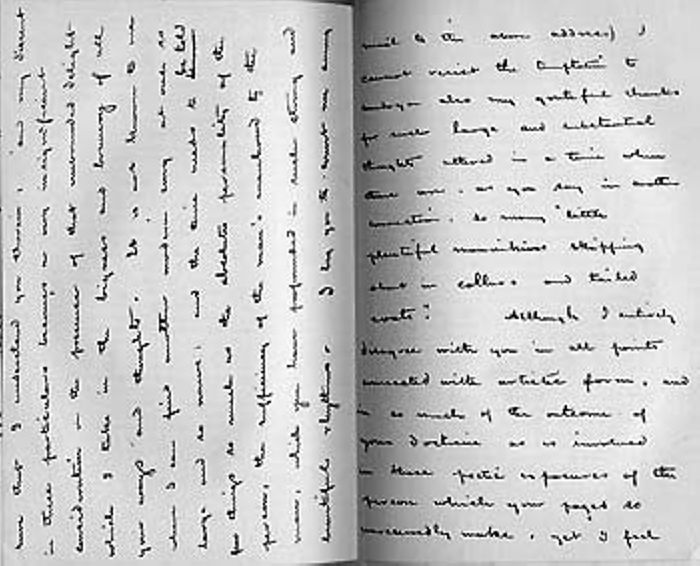

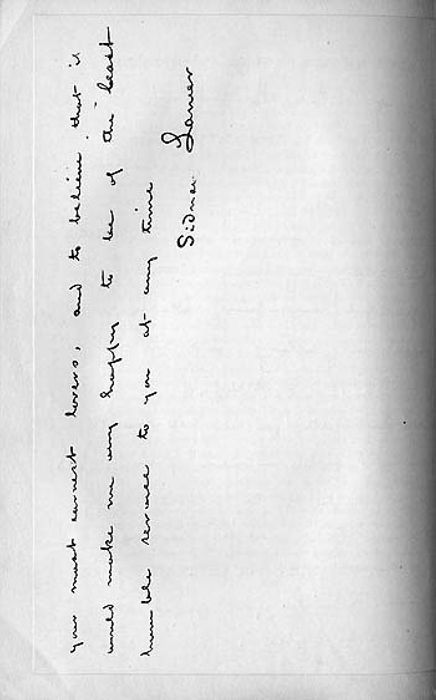

| A Lanier Letter to Walt Whitman | 208 |

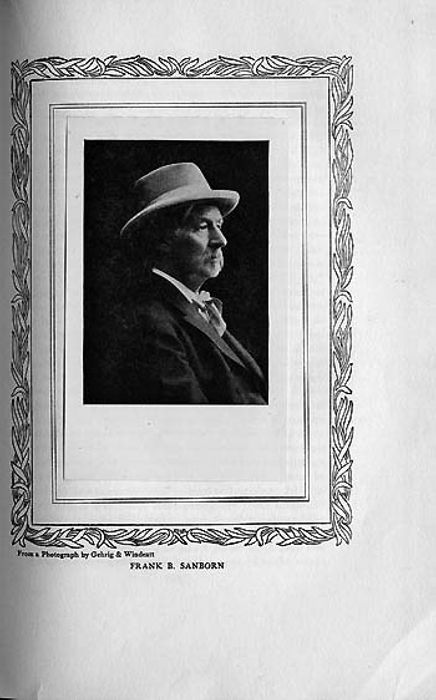

| Frank B. Sanborn | 212 |

| From a photograph by Gehrig & Windeatt | |

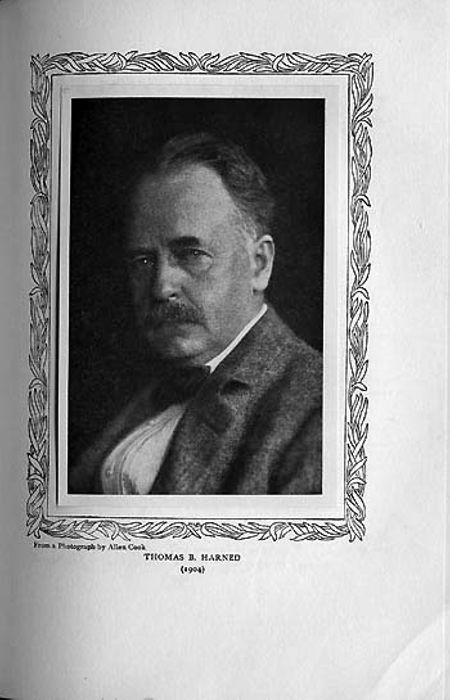

| Thomas B. Harned | 234 |

| From a photograph by Allen Cook, 1904 | |

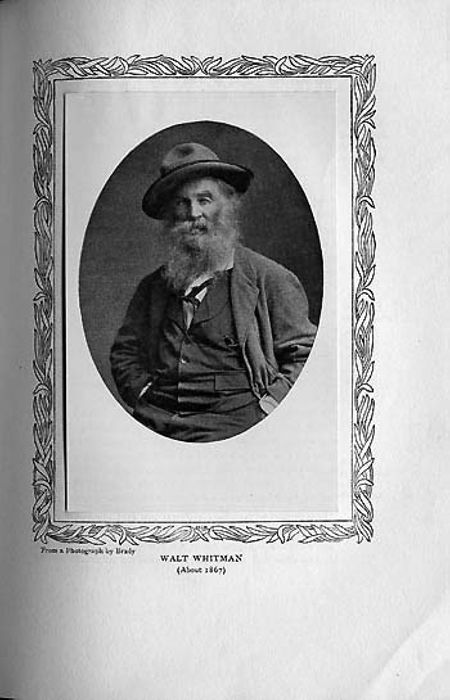

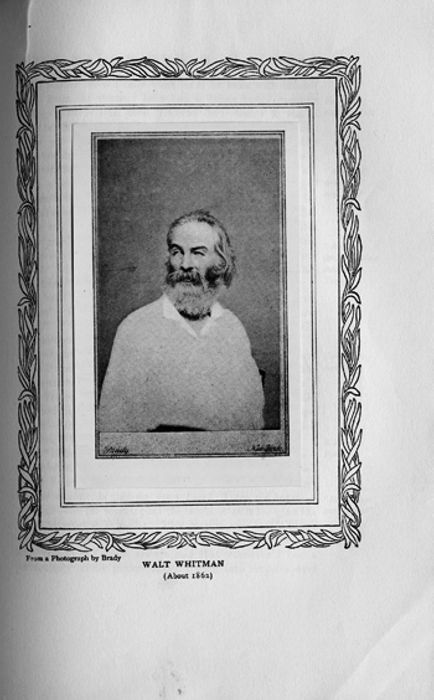

| Walt Whitman | 276 |

| From a photograph by Brady, about 1867 | |

| John Addington Symonds's Home at Davos Platz | 288 |

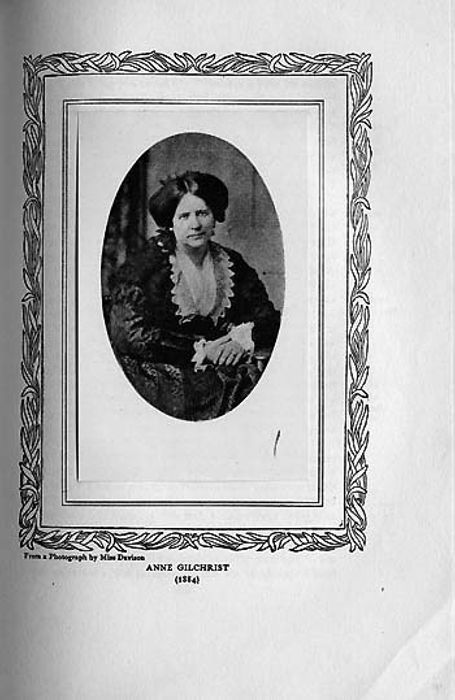

| Anne Gilchrist | 308 |

| From a photograph by Miss Davison, 1884 | |

| Walt Whitman | 334 |

| From a photograph by Brady, about 1862 | |

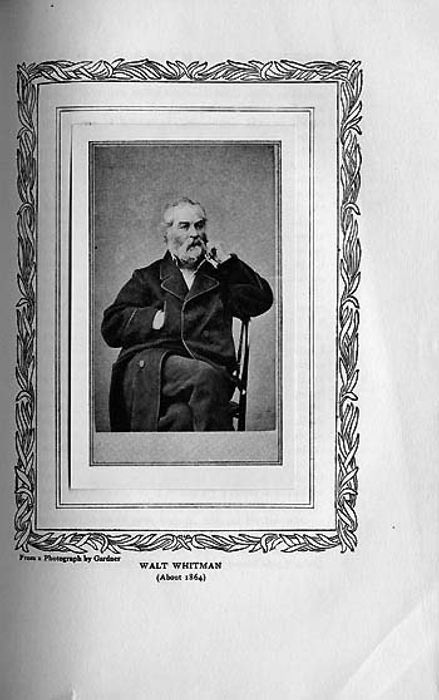

| Walt Whitman | 338 |

| From a photograph by Gardner, about 1864 | |

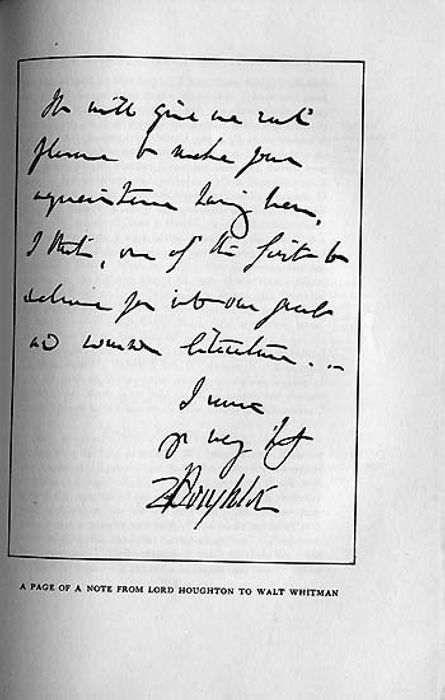

| A Page of a Note from Lord Houghton to Walt Whitman | 364 |

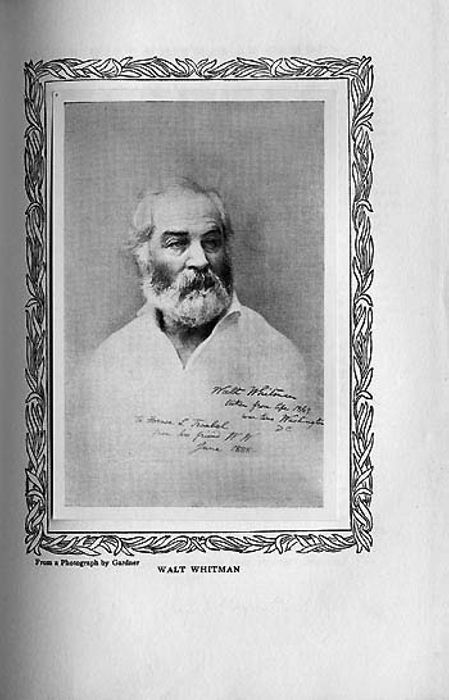

| Walt Whitman | 390 |

| From a photograph by Gardner, 1863 | |

| Rudolf Schmidt | 406 |

| From a photograph by Sinding, about 1872 | |

| Horace Traubel | 422 |

| From a photograph by Allen Cook, 1904 | |

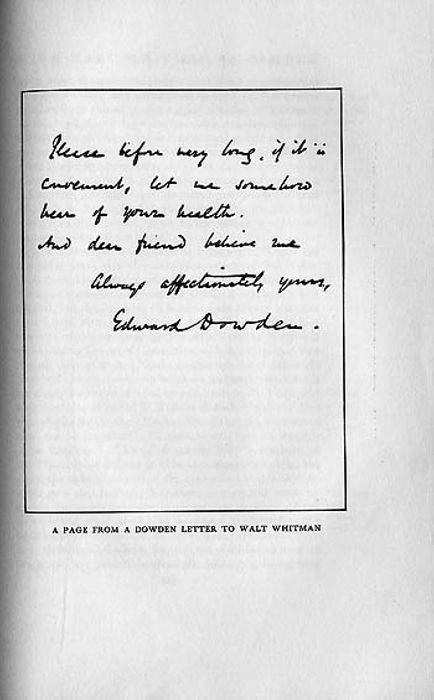

| A Page from a Dowden Letter to Walt Whitman | 444 |

| Elias Hicks | 448 |

| From a copper plate by Peter Maverick after a painting | |

| from life by Henry Inman | |

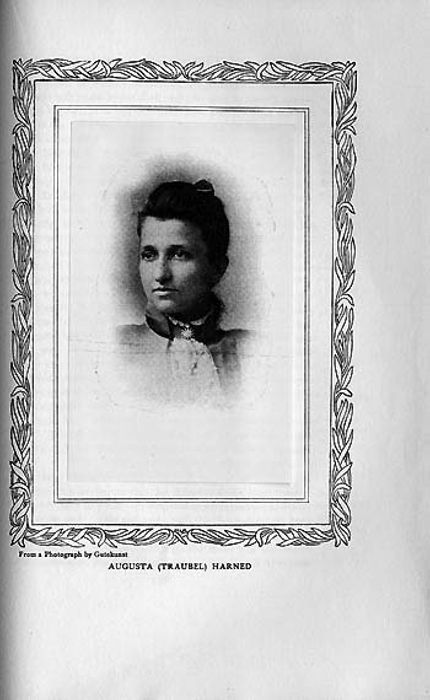

| Augusta (Traubel) Harned | 460 |

| From a photograph by Gutekunst |

LETTERS CONTAINED IN THIS VOLUME (INCLUDING OTHER MANUSCRIPTS OF WALT WHITMAN)

- Alden, Henry M., 28, 61

- American Institute, Committee on Invitations, 326

- Booth, Edwin, 46, 355

- Buchanan, Robert, 2

- Burroughs, John, 43, 89, 333, 395, 403, 404, 418

- Carpenter, Edward, 158, 189, 252

- Clapp, Henry, Jr., 236, 267

- Corson, Hiram, 286, 287

- Conway, Moncure D., 344, 346

- Curtis, George William, 85

- Dowden, Edward, 122, 133, 224, 299, 301, 441

- Eyster, Mrs. Nellie, 34

- Gilchrist, Herbert Harlakenden, 227

- Gosse, Edmund, 40, 245

- Harte, Bret, 28

- Hay, John, 60

- Hempstead, O. G. & Son, 93

- Houghton, Lord (Richard Monckton Milnes), 364

- Kelly, I. G., 9

- Kennedy, William Sloane, 377

- Knowles, James, 28

- Lanier, Sidney, 208

- Lathrop, George Parsons, 16

- Linton, W. J., 12

- Miller, Joaquin, 44, 57, 107, 360

- Morley, John, 216

- Morse, Sidney H., 406

LETTERS AND MANUSCRIPTS

- Noel, Roden, 394, 425, 432

- O'Connor, Wm. Douglas, 29, 52, 67, 83, 177, 312, 350

- O'Grady, Standish, 399

- O'Reilly, John Boyle, 8

- Palmer, George Herbert, 112

- Powell, Frederick York, 356

- Reid, Whitelaw, 463

- Rhys, Ernest, 292, 451

- Rolleston, T. W., 18

- Rossetti, William M., 132, 379, 436

- Routledge — Sons, George, 263

- Schmidt, Rudolf, 274

- Swinton, John, 24, 416

- Symonds, John Addington, 74, 203, 387, 458

- Tennyson, Alfred, 37

- Terry, Ellen, 5

- Viele-Griffin, Francis, 119

- Warner, E., 294

- Whitman, Walt, 25, 26, 36, 101, 115, 171, 192, 197, 211, 216, 219, 233, 242, 263, 281, 310, 319, 327, 339, 369, 383, 406, 414, 434, 467

- Wilmans, Helen, 49

[Inscription]

[Inscription]

WITH WALT WHITMAN IN CAMDEN

Wednesday, March 28, 1888.

At Walt's this evening. Called my attention to an old letter in the Philadelphia Press describing a visit to Emerson with Louisa Alcott, and Emerson's senility. [See indexical note p001.1] "The fact is pitiful enough but the narrative is more so: the letter is so uselessly literal, so much mathematical: has to tell it all and let it run over." He had himself seen Emerson "after the shadow." And he "saw nothing tragic or startling" in Emerson's condition. "The senile Emerson is the old Emerson in all that goes to make Emerson notable: this shadow is a part of him—a necessary feature of his nearly rounded life: it gives him a statuesqueness—throws him, so it seems to me, impressively as a definite figure in a background of mist."

W. handed me a leaf from The Christian Union containing an article by Munger on Personal Purity, in which this is said: [See indexical note p001.2] "Do not suffer yourself to be caught by the Walt Whitman fallacy that all nature and all processes of nature are sacred and may therefore be talked about. Walt Whitman is not a true poet in this respect, or he would have scanned nature more accurately. Nature is silent and shy where he is loud and bold." "Now," W. quietly remarked, "Munger is all right, but he is also all wrong. If Munger had written Leaves of Grass that's what nature would have written through Munger. But nature was writing through Walt Whitman. And that is where nature got herself into trouble." And after a quiet little laugh he pushed his forefinger among some papers on the table and pulled out a black-ribbed envelope which he reached to me: "Read this. You will see by it how that point staggers my friends as well as my enemies. We have got in the habit of thinking Buchanan is not afraid of anything—is a sort of medieval knight militant going heedlessly about doing good. [See indexical note p002.1] But Buchanan, who is not afraid of anything, is afraid of Children of Adam."

16 Up. Gloucester Place, Dorset Square, London, Jan. 8, 1877. Dear Walt Whitman:Pray forgive my long silence. [See indexical note p002.2] I have been deep in troubles of my own. All the books have arrived and been safely transmitted. Many thanks.

You have doubtless heard about affairs in England. The tone adopted by certain of your friends here became so unpleasant that I requested all subscriptions etc. to be paid over to Rossetti, and received no more myself. During a certain lawsuit against the Examiner, your admirers—notably Mr. Swinburne—pleaded against me that I had praised you, cited your words against me in court etc. [See indexical note p002.3] I never was so shocked and astonished, for I would not have believed human beings capable of such iniquity.

As I think I told you before, I shall ever regret the insertion of certain passages in your books (Children of Adam etc). [See indexical note p002.4] I do not believe them necessary or defensible. These passages are quoted as being the work of an immoral writer, and, altho' I tried to show they were part of a system of philosophy, it would not do. I know the purity and righteousness of your meaning, but that does not alter my regret.

I think your reputation is growing here, and I am sure it deserves to grow. [See indexical note p002.5] But your fatal obstacle to general influence is the obnoxious passages. I wish you would make up your mind to excise them with your own hand.

God bless you!—May your trouble lift, and may happy days be in store for you!—Let me know about your affairs. I may soon be in a position to help you more definitely.

Yours ever, Robt. Buchanan.W. watched me as I read the letter and when he saw I was through resumed: "Children of Adam stumps the worst and the best: I have even tried hard to see if it might not as I grow older or experience new moods stump me: I have even almost deliberately tried to retreat. [See indexical note p003.1] But it would not do. When I tried to take those pieces out of the scheme the whole scheme came down about my ears. I turned Buchanan's letter up today in a heap of nothings and somethings. I guess Buchanan and Munger would not agree about lots of the subsidiary things but here the preacher and the radical come together: though as for that there is a difference between them even in this thing: for while Munger talks of the 'fallacy' as though it was fundamental to Buchanan I am only guilty of a lack of taste. [See indexical note p003.2] Well—there are the pieces, to sink or swim with the book: and here is Walt Whitman to sink or swim likewise."

Thursday, March 29, 1888.

"I have been making a few notes to-day," said W., "on the subject of my removal from the Interior Department. As you know, Secretary Harlan took the Leaves even more seriously than Munger: he abstracted the book from my desk drawer at night after I had gone, put it back again, and discharged me next day. [See indexical note p003.3] I suppose I felt harder about the affair at the time than I do now: it is easy to be unjust to a man like Harlan. He was of the sincere fanatic type, given to provincial views, ignorant of literature, in many ways that I consider essential ignorant of life. To Iowa as Iowa Walt Whitman as Walt Whitman was not easily digestible: so Whitman as the author of an indecent book had to go. Harlan was so dead in earnest that when his action was disputed by influential people he simply declared that he would resign his folio rather than reinstate me: which was all right for Harlan and all right for his kind of Iowa. I was taken care of by being given a desk in the Attorney-general's office. [See indexical note p004.1] The more or less anonymous young writers and journalists of Washington were greatly incensed—made my cause their own—wrote almost violently about it: but the papers generally as well as literary people either ignored the incident altogether or made light of it. This was the hour for O'Connor: O'Connor was the man for this hour: and from that time on the 'good gray,' William's other name for me, has stuck—stuck. I was told by a man then very close to Lincoln that this obtuseness in Harlan had gone a great way towards nullifying his ambitions for the Vice-Presidency: that the opposition underground from the press and even from the more tactical politicians had cut the foundations from under his feet. Not that this quarrel [See indexical note p004.2] with me could have had such an effect alone but because it was symptomatic—had simply served to accentuate certain unfortunate traits of character in the man. Long after Harlan acknowledged to one of the newspaper fellows in St. Louis: 'The removal of Whitman was the mistake of my life.'"

[See indexical note p004.3] In speaking on the subject today W. said to me that "the radical element in Lincoln was sadness bordering on melancholy, touched by a philosophy, and that philosophy touched again by a humor, which saved him from the logical wreck of his powers."

Friday, March 30, 1888.

[See indexical note p004.4] Happening to refer to something Ellen Terry had said about him in Chicago, which had been repeated to me in a letter, W. laughingly exclaimed: "We have heard from her

From a Photograph by Merrit & Wood; William Douglas O'Connor (1887)

direct on that point. Let me see—where is that letter? Oh, yes! I know!" He reached to the floor and picked up a book. "I remembered I had used it for a bookmark. It came several months ago. Here it is." This is the letter:

From a Photograph by Merrit & Wood; William Douglas O'Connor (1887)

direct on that point. Let me see—where is that letter? Oh, yes! I know!" He reached to the floor and picked up a book. "I remembered I had used it for a bookmark. It came several months ago. Here it is." This is the letter:

I beg you to accept my appreciative thanks for your great kindness in sending me by Mr. Stoker the little big book of poems—As a Strong Bird, etc., etc. [See indexical note p005.1]

Since I am not personally known to you I conclude Mr. Stoker 'asked' for me—it was good of him—I know he loves you very much.

God bless you dear sir—believe me to be with much respect

Yours affectionately, Ellen Terry.W. had written on the outside of the envelope: "from Ellen Terry." He regarded me with a whimsical eye: "You have a hungry look: I think you want the letter. Well—take it along. You seem to cultivate that hungry look: it is a species of pantalooned coquetry." [See indexical note p005.2] I put the letter in my pocket. "These actor people," pursued W., "always make themselves at home with me and always make me easily at home with them. I feel rather close to them—very close—almost like one of their kind. When I was much younger— way back: in the Brooklyn days—and even behind Brooklyn—I was to be an orator—to go about the country spouting my pieces, proclaiming my faith. I trained for all that—spouted in the woods, down by the shore, in the noise of Broadway where nobody could hear me: spouted, eternally spouted, and spouted again. [See indexical note p005.3] I thought I had something to say—I was afraid I would get no chance to say it through books: so I was to lecture and get myself delivered that way. I think I had a good voice: I think I was never afraid—I had no stage reticences (I tried the thing often enough to see that). [See indexical note p006.1] For awhile I speechified in politics, but that, of course, would not satisfy me—that at the best was only come-day go-day palaver: what I really had to give out was something more serious, more off from politics and towards the general life. But the Leaves got out after all—in spite of the howl and slander of the opposition, got out under far better conditions than I expected: and once out went along— stormily, fiercely, rocked and shaken—until within hail of its audience. [See indexical note p006.2] I have wandered some distance from Terry: her letter made me reminiscent—this largely because the actors have always been more friendly to me than almost any other professional class, and she reminded me of it. Great woman! She reminded me of it."

Sunday, April 1, 1888.

At Harned's. A crowded table. W. in fine fettle. Felix Adler there: also Tom Dudley, once consul at Liverpool and now retired. Dudley is among high-tariff apostles as high as any. [See indexical note p006.3] W. is a free trader. The talk went hot, hit and miss, on the tariff. W. declared: "I am for getting all the walls down—all of them." "So I suppose," said Dudley, sarcastically: "even the walls between the planets, if you could." "If I could, yes," retorted Walt, with spirit: "that's what the astronomers are working all their days and nights, especially nights, to do!" He was even more explicit as the argument proceeded: "While I seem to love America, and wish to see America prosperous, I do not seem able to bring myself to love America, to desire American prosperity, at the expense of some other nation or even of all other nations." [See indexical note p006.4] "But must we not take care of home first of all?" asked Dudley. "Perhaps," replied W.: "but what is home—to the humanitarian what is home?"

At the table Dudley toasted Lincoln. Opposite Whitman, on the wall, was a portrait of Lincoln. [See indexical note p007.1] When Dudley offered the toast, W. lifted his glass, turned his eyes up to the picture and exclaimed: "Here's to you! Here's to you!" Adler cried: "I shall always wish to remember Whitman as he looked at that moment." And to the table in general Adler remarked: "I feel honored in having three things in common with Mr. Whitman—I like coffee, I admire Millet and I love the lilac!"

W. caught at the name of Millet. [See indexical note p007.2] "Yes, there's Millet—he's a whole religion in himself: the best of democracy, the best of all well-bottomed faith, is in his pictures. The man who knows his Millet needs no creed." Harned interjected this question: "If Millet is enough and to spare what's the use of Leaves of Grass?" "That's what I say," replied W.: "If I had stopped to ask what's the use I never would have written the Leaves: who knows, Millet would not have painted picture! The Leaves are really only Millet in another form—they are the Millet that Walt Whitman has succeeded in putting into words." [See indexical note p007.3] Dudley broke in: "But what about the Constitution of the United States while all the rest is going on?" W. laughed: "Good for you, Dudley. After Millet and Whitman we seem to have left little room for anything else. What about the Constitution? What about last year's almanac, the weeds back there on the lot, the ash heap down the street? I guess these things crowd into the scheme after all; and after all Millet and Whitman need not feel so lonely."

W. is often described as lacking humor. [See indexical note p007.4] But this quiet play of pros with cons enters more or less into all his conversation. One of Harned's little boys slid himself off his high chair, after being thoroughly bored with our tiresome sallies in economics and philosophy, and remarked, to nobody in particular: "There's too much old folk here for me!" [See indexical note p008.1] W. heard the youngster, laughed heartily, and declared: "For me too: let's all get young again. We are all of us a good deal older than we need to be, than we think we are. Most of the brilliant things we have been saying to each other here are very old, very few of them are very good. I don't know but I might as well say for us all, as well as for myself, that this is a sort of bankruptcy court of ideas. Yes—yes—there's far too much that's old here—far too much. That is, always excepting Dudley, whose seventy years don't count!"

Monday, April 2, 1888.

[See indexical note p008.2]Mousing among some old papers on his table today, looking for something else, W. spilled out a letter which he first scanned himself and then passed over to me, saying: "If ever a fighter lived, Boyle O'Reilly is that fighter: he writes me fiery letters, he tells me fiery stories. Have you never met him? No? I shall never forget the first time he spoke to me about his prison life. He was all alive with the most vivid indignation—he was a great storm out somewhere, a great sea pushing up the shore. Read this letter. It is mild for him. Then read the letter he enclosed."

The Pilot Editorial Rooms, Boston, Feb. 11, 1885. Dear Mr. Whitman, [See indexical note p008.3]I have received the enclosed letter today from one of the ablest men I have ever known; and I send it to you as another little proof that Irishmen understand and honor you. I hope you are well. Somebody told me lately that you had been in Boston within a month; but I could not believe that you would have gone away without letting me have the pleasure of seeing you.

[See indexical note p008.4] Bartlett is happy, and busy; but he has no more money than he had two years ago. His son is now with him, and they are finishing two portrait busts of rich men.

Mrs. Fairchild, whom you will remember, is never done preaching you and your work. [See indexical note p009.1]

Good-bye.

Faithfully yours, Boyle O'ReillyThe enclosed letter follows:

39 Bowdoin Street [Boston] 10, 2, '85. My Dear Boy,I am very grateful to you for inducing me to read Walt Whitman. He is to me that which he claims to be to all his readers, a Revelation and a Revealer. He has marshaled facts and sentiments before my mind's eye which have been floating, vaguely and transiently, through my consciousness since I commenced to be untrammeled in thought: he has given me views which help to render my 'dark days' endurable and my nights teem with companions. [See indexical note p009.2] When I read Walt Whitman nature speaks to me: when I read nature Walt Whitman speaks to me. He travels with me and he points out the goodness of men and things and he intensifies my pleasures by his presence and sympathy. Leaves of Grass! so like "the handkerchief of the Lord"! covering the face of creation with love and pity and admiration for "man and bird and beast" and thing! How sad that for a few 'bare' expressions it should be kept out of the hands of the multitude and the women and the children!

I thought I knew the greatest American in my dear friend Henry George, but no! [See indexical note p009.3] Walt Whitman (whom he admires) is still greater, as a philanthropist, a democrat and a philosopher. He also excels your greatest theologians, naturalists, scientists and poets. He is an intellectual colossus or individuality, which admits of no comparison. He is not a poet and still he is greater than any—no dramatist and yet his characters breathe and strive and even smite you at his will: he knows little of the names of plants and animals, but he makes nature a domestic panorama: he can hardly be termed a religious man, yet he overflows with Faith and Hope and Love: he has no rank as a politician, yet his principles, if grasped, would revolutionize the world. [See indexical note p010.1] Thus, he is everything and yet—nothing but Walt Whitman, a distinction which should satisfy the most craving ambition.

I am your friend and debtor I. G. Kelly.W. had pencilled this on the note: "Sent me by Boyle O'Reilly Feb. 85." [See indexical note p010.2] When he saw I had got through with the second letter he asked: "What do you think of that for a broad summing up? Barring any extreme statement, he seems to hit several real proper nails on their heads—gets pretty close to my ribs. The man with eyes to see that substance in my work must first of all have had it all in himself: we know that so well, so indubitably, so without disposition to quarrel or doubt, that it saves us from vanity. That man Kelly must be of the most real kind of real stuff. I like especially what he says about religion. [See indexical note p010.3] I claim everything for religion: after the claims of my religion are satisfied nothing is left for anything else: yet I have been called irreligious—an infidel (God help me!): as if I could have written a word of the Leaves without its religious root-ground. I am not traditionally religious—I know it: but even traditionally I am not anti: I take all the old forms and faiths and remake them in conformity with the modern spirit, not rejecting a single item of the earlier programs."

Tuesday, April 3d, 1888.

W. in good shape. Speaks optimistically about his health. [See indexical note p010.4] "I am of course only gradually though surely losing strength, but the experiences going with this do not disturb me: no man housed up as I am could expect to hold his ground against old age. But I am convinced that I can feint off the end for a long time to come: I am not anxious to, only determined upon it: we are not going to expect to lose even a losing fight—that would not be like us: we are not easily subdued: we must stick, eternally stick, until sticking itself will stick no more." [See indexical note p011.1]

He gave me some books to deliver to two or three persons in Philadelphia to whom he felt indebted for courtesies. He is always giving away books. He sent copies of the two volumes 1876 edition by me to Adler. [See indexical note p011.2] "Adler," he says, "is first rate soil. He is all gone on ethics. Worse things might happen to him, though ethics is bad enough. I do not see how these Ethical fellows can expect to do much as an opposition to the church: they may stir the church up, plague it into reforms, changes, even revolutions—but the church is bound to continue to be the church imminent—imminent, imperative. [See indexical note p011.3] People have thought I was powerful 'set agin' the church: but the church has not bothered me—I do not bother the church: that is a clean cut bargain. I am done with the letter of the church—with its hands and knees: but that part of the church which is not jailed in church buildings is all mine too, as well as anybody's—all of it, all of it!"

My mother had sent W. some cookies. "The best part of every man is his mother," said W. [See indexical note p011.4] I told him of one of his girl friends who had just given birth to a boy baby. "She will be too proud to go with us when she gets up," he jocularly remarked—adding: "But any mother of any baby has a right to be proud."

Back of him on the wall was a pencilled figure of a rather ragged looking nondescript. "Where did you get that?" I asked. "Would you believe it—the tramp himself was here this morning." [See indexical note p011.5] He was a curious character—an itinerant poet: and he read me some of his poems: Lord pass him, what stuff! But it was his own, written on the road. It made me feel bad to think that he could go along in the sun and rain and write while I am housed up here in the dust of a dead room eking out my substance in coalstove words." "Coalstove" was good. [See indexical note p012.1] But he burns wood in his stove. But how did he come by the picture? "The poet said he had drawn it himself sitting on a field outside Camden somewhere before a bit of a broken looking glass, which he had balanced on his knee." He reflected as I left: "When I said goodbye to the tramp I was envious: I could not see what right he had to his monopoly of the fresh air. He said he was bound for some place in Maryland. I shall dream of Maryland tonight—dream of farm fences, barns, singing birds, sounds, all sorts, over the hills."

Wednesday, April 4, 1888.

W. not so well. [See indexical note p012.2] "I am not down in the mouth about it," he explained, "but I am still jealous of that tramp: I suppose he's bummin' along somewhere on the road eatin' apples and feelin' drowsy and doin' as he pleases—and here am I in this room growlin' with a bellyache. What is the use of poetry or anything else if a man must have a bellyache with it?"

W. gave me an old letter from Linton. "This stuck its head out from a bunch over there this morning and I grabbed it. Take it along—put it among your souvenirs. That bunch of your souvenirs must be getting a bay window on it."

New Haven, Conn., May 19, 1875. My Dear Whitman:[See indexical note p012.3] Why have I not written to you? Why has not spring come? I have waited for that, waiting a little also till I could get through some work which would have made me uncompanionable.

Now—I go to New York on Saturday June 5 to the Century meeting and remain in New York till Tuesday or Wednesday after. Can not you meet me so as to return home with me? Apple blossoms surely will be out by then, and some summer warmth to enable you to enjoy your hammock (did I tell you I have one?) on the piazza. [See indexical note p013.1] I want you here and to set you to rights. Can you come then (not for a night or two but to stay indefinitely) or will you rather come later?

Do which may best suit you; but come; and let me know as near as you can when I may look for you.

Affectionately yours W. J. Linton.I want a copy of your Mystic Trumpeter for England.

Thursday, April 5, 1888.

"I feel so good again today," W. assures me, "that I no longer envy the tramp. [See indexical note p013.2] I think that dusty cuss did me lots of good: he left me temporarily in a quarrelsome mood: I hated the room here, and my lame leg, and my dizzy head: I got hungry for the sun again, for the hills: and though Mary brought me up a good supper she didn't bring the sort of food required to satisfy a fellow with my appetite. She didn't bring the sun and the stars and offer them to me on a plate: she brought muffins, a little jelly, a cup of tea: and I could have cried from disappointment. [See indexical note p013.3] But later, next day, yesterday, the tramp's gift got into my veins—it was a slow process, but got there: and that has made me happy. I thought he had taken everything he had brought away with him again: but I was mistaken. He shook some of his dust off on me: that dust has taken effect."

Friday, April 6, 1888.

"Not the negro," said W. today: "not the negro. [See indexical note p013.4] The negro was not the chief thing: the chief thing was to stick together. The South was technically right and humanly wrong." He discussed the present political situation in a rather more explicit way than is usual with him. He "cares less for politics and more for the people," he explains: "I see that the real work of democracy is done underneath its politics: this is especially so now, when the conventional parties have both thrown their heritage away, starting from nothing good and going to nothing good: the Republican party positively, the Democratic party negatively, the apologists of the plutocracy. You think I am sore on the plutocracy? [See indexical note p014.1] Not at all: I am out to fight but not to insult it: the plutocracy has as much reason for being as poverty—and perhaps when we get rid of the one we will get rid of the other." W. will not talk persons in his censure. He says he will talk persons only in his love. "When I hit I want to hit hard, but I don't want to hit any man, the worst man, even the scoundrel, one single blow that belongs to the system from which we all suffer alike." [See indexical note p014.2] Could this suffering have been avoided? "No more than the weather: it is as useless to quarrel with history as with the weather: we can prepare for the weather and prepare for history." Then was history automatic? "Not at all: it is free in all its basic dynamics: that is, the free human spirit has its part to perform in giving direction to history." Was this statement not self-contradictory? "I shouldn't wonder: in trying to represent both sides we always run some risk of finishing on the vague line between the two." He admitted that there was "no practical politics in this kind of talk," but then: [See indexical note p014.3] "What do I want with practical politics? Most all the practical politics I see anywhere is practical villainy." Did he see anything within the political life itself in America at present to excite his hope? "Absolutely nothing: not a head worth while raised above the surface: not a cross section of a party, or a clique even in any party anywhere, to promise a formidable reaction and advance." Then he was despondent? "Not a bit so, for you see I am not looking to politics to renovate politics: I am looking to forces outside—the great moral, spiritual forces—and these stick to their work, through thick and thin, through the mire and the mirage, until the proper time, and then assume control." Finally he said: "The best politics that could happen for our republic would be the abolition of politics."

Saturday, April 7, 1888.

W. is always a good deal interested in public discussions of the college. [See indexical note p015.1] How much freedom could be expected in the atmosphere and teaching of the schools? "To what extent can professors and editors, scholars tied up with institutions and writers writing for their daily bread (and writing under the severest conditions) be expected to talk out and defy the formal monitors of speech?" W. says the college is "of necessity an aristocracy." We have often gone over that same ground. [See indexical note p015.2] Today he revived the subject by producing a letter from Lathrop written to Burroughs in 1877. "This," W. contended, "shows how serious such difficulties are—how far they crawl serpent-like out from the college walls into the general world." To him Lathrop's letter was "touched with spiritual tragedy." "Hope deferred makes the heart sick—so does speech deferred." But what can a man do when he finds himself driven up against that wall? [See indexical note p015.3] "Come forward and make a peaceful surrender, be dragged out and grudgingly capitulate or stand where he is and be shot." This confession from Lathrop, W. contended, served to show why it would "be impossible for such a man, fine as he is, fine as his letter is, to really build up and round out a capacious career": there was a "lesion somewhere in his marrow." He looked at me and seemed to see some distrust in my face. "You think I am condemning Lathrop? Thousands from it! I love him—honor him: if there's anything comes short it excites my regret: I judge no one." This is the letter:

Cambridge, May 19, '77. My dear Mr. Burroughs,[See indexical note p016.1] I have just finished your book on Birds and Poets. I like your writing, always, and I have keenly enjoyed this. But you will not quarrel with me if I pass that matter over, in order to speak of Walt Whitman. Ever since I first gained some fragmentary knowledge of him thro' the pruned and lopped English edition, I have not for a moment flagged in the belief that he is our greatest poet, altogether, and beyond any measurement. He threw open a wide gate for me, and I passed through it gladly—thinking to be able in my separate way to make a kind of companionship with him. [See indexical note p016.2] From the start, my intentions have been very different in some respects from those of which he has given such huge exemplification; but, as I took to his poetry without any premonitory shrinking, and felt that at last here was something real, I knew that I should in some measure respond to his voice in what I should do, however far off, however fainter, and however much unlike in seeming it might be.

But my circumstances have been strangely hampering. I find myself in the midst of the camp which adheres to the old and the conventional. I am an accepted servant in it, trying to pass through my bondage patiently, working year after year in a roundabout way slowly trying to secure my position, and hoping at last to be able to let out the accumulating thunder in my own way. I get my hands loose now and then, and feel that I have done a little something. This much I thought it necessary to say because I suppose you at a distance hardly imagine that a young Cambridge literary apprentice can say his soul's his own or cherish in himself a whole revolution against the powers whom for a time he is working with. [See indexical note p016.3] I say it also, to explain why I would like now to convey through you to Walt Whitman some message expressing the fact that I have long wished to speak a word of gratitude to him. To a man so wronged even this little tribute may have its value. It is also a great satisfaction to me to think of speaking the truth about him to him and through one who understands it. [See indexical note p017.1] There are two persons hereabouts who appreciate Whitman, whom I know. Doubtless there are many more who are unknown to me. But I can believe that the scoffing narrowness which meets any avowal of their appreciation has driven them, as it has me, to preserve silence.

It is a great pity his works are not really published, and I have been wondering, long, how to get them. I have nothing but Rossetti's edition. Is there no way of obtaining them? I should be very glad if you would inform me as to this.

I frequently debate plans of some change of base, so as to secure something approaching independence. I was not born in New England, tho' of Puritan descent, but in the tropics. [See indexical note p017.2] I like many things here and dislike others as much. I am a great lover of cities for their crowds, their human sublimities and horrors, yet carry always an insatiable yearning for the wilds. I don't know where to go, if I go from here, where I am now editing the Atlantic with Mr. Howells; but I have before now thought of your region. I have no map showing Esopus. Is it in the Highlands—anything like Milton? Would you be willing to tell me something of your mode of life, or whether one can subsist in that vicinity on slender means?

Sincerely yours, G. P. Lathrop.Sunday, April 8, 1888.

"We are having our troubles in getting out that book," W. reflected, speaking of the German Whitman: "though as for that matter I do not know any edition with which we didn't have enough trouble and trouble running over." [See indexical note p017.3] We had got upon this subject because of an old letter from Rolleston which Walt had given me to read. "There's a lot in that letter describing the way the book is coming about: it is typical history—especially that possible encounter with the German police. [See indexical note p018.1] The Leaves have had several set-tos with the state, none of them serious, all of them serving to advance the book—Harlan's, to begin with, then Stevens', in Massachusetts, then that fool postmaster Tobey's. The funny underground in all this was the warning I got now and then from good attorneys general and their heirs and assigns that if I didn't modify my literary manners something would happen to me. Something has happened—but not just the something that was conveyed by their warnings." This is Rolleston's letter:

Glasshouse, Shinrone, Ireland, September 9, 1884. My dear Walt—I got your second letter yesterday, forwarded here from Dresden. [See indexical note p018.2] Don't be uneasy about the English text in translation. I fully see the advantages of it and have mentioned it in my Preface. Only, as I had had no opinion on the subject from anyone in the publishing line I didn't know what they might not have to advance, so did not like to speak so decisively about it. I should not have given you to understand that a publisher's mere opinion would weigh with me, for it would not.

Now, as to progress made. I have met with difficulties more serious than I expected. The work is ready, and could go to the printer any day. But the printer is not equally ready for the work. [See indexical note p018.3] I offered it to four publishers before I left Germany, agreeing to pay all expenses myself, and all refused to take it up. I sent with my MS. a copy of Freiligrath's article, and did all I could to secure a favorable hearing, but in vain. I am told there would probably be difficulties with the police, who in Germany exercise a most despotic power. Then other publishers I thought of trying are, I have been informed, rogues; and others again are dependent in various ways on court or official patronage—others wouldn't touch it with the end of a poker. I finally came to a resolution a good deal confirmed by what you said of the probable circle of readers of the first edn—namely, to let the work appear in America, and thence make its way into German circulation. [See indexical note p019.1] Once in print and fairly before the public it will of course weather every storm, but the thing is to get it fairly started. Had I been living in Germany longer I should have tried selling the book myself—but that I can't do from here. Now in America, where your position is assured, I suppose some German publisher would take it up readily enough. [See indexical note p019.2] I am going then to ask you to take what steps can be taken towards finding a willing publisher with some German connection. No doubt Dr. Karl Knortz would be a useful person to apply to. (If you know him, and could get him to glance through my proofsheets, I don't doubt that the work would be considerably improved.)

As to terms, of course if any enterprising publisher would give me one hundred dollars or so for the book I would let him have it (it being understood that you and I should have our way about the form of the book, English version, &c.). [See indexical note p019.3] But I would be willing also to bear the expenses and keep the copyright, if the former were not out of the way large. I suppose it would cost a good deal more in America than in Germany, where everything is very cheap, and I have not much ready money to spare now. But I think I can rely on my father's helping me to the extent needed. If the book is printed in America you will be able to oversee technical matters connected with the printing to your own satisfaction.

So the upshot of this is that I will send you my MS. as soon as it reaches me (it is coming in a box which was sent after me via Hamburg with other heavy luggage), and you can do as you think well with it. [See indexical note p019.4] Let me say again that I should greatly like the proofsheets, before coming here, to pass through the hands of some German scholar who knows the L of G. I should be grateful for any annotations he might wish to make.

I have grieved to hear of your increased illness. It is very hard to be persecuted by such things when you ought to have peace and freedom. But I know how you are "armed with patience." Silence is a great comforter.

[See indexical note p020.1] We are now back in our own country for good and are greatly delighted to be so. The people are much more congenial to me than Germans, though these latter are more so than English. I was born in this town and know every field and nearly every tree since my childhood. It is wonderfully beautiful to me—a rich, undulating, wooded land—deep grass and crops—blue mountains of Slieve Bloom on the horizon, and the stateliest trees, mostly ash and beech, I ever saw. I have a great love for ash trees—such sinewy strength, and a free powerful method of branching, showing through the light foliage. What a country this is! or would be but for savage misgovernment, and Protestant bigotry. The Orangemen in the North are a source of much evil, and will be of more, unless some miracle should turn them into human sympathetic Irishmen. There was a time when I thought that Ireland could never be set free from English rule because the Catholic Church would instantly become dominant and inaugurate a system of religious tyranny which would crush liberties more important than national liberties. Now I begin to see that this would not be so for long. [See indexical note p020.2] The Irish are much less Catholic than they were—dogmatic religion is loosening its hold upon them in a very remarkable way, and hatred for Protestant England as Ireland's ruler is a most potent cause at present in supporting the Catholic religion here. This is felt even by the more cultivated and far-seeing of the clergy, who consequently oppose the national movement as far as they dare. I have no doubt that in a free Ireland the Church would

MICKLE STREET, CAMDEN, NEW JERSEY

persecute as naturally as a wasp stings, but I am equally certain that a revulsion of feeling would come which (though attended perhaps with terrible struggles) would mark a real moral and intellectual advance such as seems out of our reach at present. The people about us here are very poor, reckless, friendly, "full of reminiscences" both of good and evil. My father is greatly loved far and wide because when County Court Judge of Tipperary he protected the tenants as far as the laws allowed against the rapacity of the landlord class. [See indexical note p021.1] He is a man you would like to see. He is over seventy now, more than average height even for our family, where men grow very tall (about six feet four inches), and still sturdy. At present he is suffering from a strain got a few days ago while riding a restive horse. They tell me that a few days before I came there was a storm, and a fine sycamore he was fond of was being blown down. They saw the roots heaving through the loosened earth—and my father sat down upon them until heavy weights could be brought to keep them downtill the storm blew out, a device which was perfectly successful. He and my mother are greatly delighted with the two grandchildren we have brought them home. I'll send you a photograph of them soon, which has been done in Dresden just before we left.

MICKLE STREET, CAMDEN, NEW JERSEY

persecute as naturally as a wasp stings, but I am equally certain that a revulsion of feeling would come which (though attended perhaps with terrible struggles) would mark a real moral and intellectual advance such as seems out of our reach at present. The people about us here are very poor, reckless, friendly, "full of reminiscences" both of good and evil. My father is greatly loved far and wide because when County Court Judge of Tipperary he protected the tenants as far as the laws allowed against the rapacity of the landlord class. [See indexical note p021.1] He is a man you would like to see. He is over seventy now, more than average height even for our family, where men grow very tall (about six feet four inches), and still sturdy. At present he is suffering from a strain got a few days ago while riding a restive horse. They tell me that a few days before I came there was a storm, and a fine sycamore he was fond of was being blown down. They saw the roots heaving through the loosened earth—and my father sat down upon them until heavy weights could be brought to keep them downtill the storm blew out, a device which was perfectly successful. He and my mother are greatly delighted with the two grandchildren we have brought them home. I'll send you a photograph of them soon, which has been done in Dresden just before we left.

I will have the poems arranged in the order I find best, but you of course may wish to alter my arrangement, in which case I shall have nothing to object. I couldn't make out what 'teffwheat' is (Salut au Monde)—is there a German equivalent? I have written Teff-Weizen.

Yours, T. W. R."Rolleston," said W., "has proved to be one of my staunchest friends. [See indexical note p021.2] He is a man without extravagance or excuse: he never says I am the only man that ever was, he never says I need to be apologized for." [The translations that form the chief subject matter of the letter did finally come out (1889) from Zürich, under the imprint of J. Schabelitz, with the names of both Knortz and Rolleston on the title page as translators. Harned happening in while we were in the midst of this talk W. explained: "We are canvassing the yeas and noes on the Rolleston book: it will come out but it is having the usual amount of stops, starts, stumbles."

Monday, April 9, 1888.

[See indexical note p022.1] "Tucker," said W., "has been giving me the very devil in Liberty for calling the Emperor William a 'faithful shepherd' in my poem. In fact, Tucker is not alone: I have got a whole batch of letters of protest—one, two, three, a dozen; but too many of the fellows forget that I include emperors, lords, kingdoms, as well as presidents, workmen, republics." We talked the matter over for some time. W. was good natured about it all. Yet he was disposed to regard the criticism rather seriously. As he said: "It is all from my friends. Take William O'Connor—take Tucker himself—they deserve to be listened to." In winding up our chat he said: "I see I must be careful in such things or maybe the boys will think I am apostate. [See indexical note p022.2] Yet they ought to be just to me, too. There was nothing in this little poem to contradict my earlier philosophy. It all comes to the same thing. I am as radical now as ever—just as radical—but I am not asleep to the fact that among radicals as among the others there are hoggishnesses, narrownesses, inhumanities, which at times almost scare me for the future—for the future belongs to the radical and I want to see him do good things with it."

[See indexical note p022.3] Matthew Arnold was mentioned: "Arnold has been writing new things about the United States. Arnold could know nothing about the States—essentially nothing: the real things here—the real dangers as well as the real promises—a man of his sort would always miss. Arnold knows nothing of elements—nothing of things as they start. I know he is a significant figure—I do not propose to wipe him out. He came in at the rear of a procession two thousand years old—the great army of critics, parlor apostles, worshippers of hangings, laces, and so forth and so forth—they never have anything properly at first hand. Naturally I have little inclination their way. [See indexical note p023.1] But take Emerson, now—Emerson: some ways rather of thin blood—yet a man who with all his culture and refinement, superficial and intrinsic, was elemental and a born democrat." I put in: "I think Emerson was born to be but never quite succeeded in being a democrat." W. was still for an instant. Then: "I guess the amendment is a just one—I guess so, I guess so. But I hate to allow anything that qualifies Emerson."

Just as I was about to leave W. reverted to the Emperor William affair: "Do you think I had better write a little note to my friends making that line a little clearer?" "I thought you never explained?" "I never do explain—rather, I never have explained: yet the rule is not arbitrary." "A rule you can't break is no good even as a rule." "That is true—true—if I wrote I would do no more than make it clear that my reference was to the Emperor as a person—that my democracy included him: not the William the tyrant, the aristocrat, but the William the man who lived according to his light: I do not see why a democrat may not say such a thing and remain a democrat." [See indexical note p023.2]

Tuesday, April 10, 1888.

[See indexical note p023.3] Happening to mention John Swinton, W. said: "By the way—here's an old letter of John's that will interest you—it was written four years ago: yes, fully four years ago, and in one of his milder moods. John, you know, is stormy, tempestuous—raises a hell of a row over things—yet underneath all is nothing that is not noble, sweet, sane. This letter is almost like a love letter—it has sugar in it: I don't think America has ever realized, perhaps ever will realize, John's greatness—the significance of his work: his dynamic force. I don't suppose John has written anything that will live—yet something else of him will live—something better than things people write." I sat down on a pile of books and read the letter.

134 East 38th St., New York, Jan. 23, 1884. My beloved Walt—I have read the sublime poem of the Universal once and again, and yet again—seeing it in the Graphic, Post, Mail, World, and many other papers. [See indexical note p024.1] It is sublime. It raised my mind to its own sublimity. It seems to me the sublimest of all your poems. I cannot help reading it every once in a while. I return to it as a fountain of joy.

My beloved Walt. You know how I have worshipped you, without change or cessation, for twenty years. While my soul exists, that worship must be ever new.

[See indexical note p024.2] It was perhaps the very day of the publication of the first edition of the Leaves of Grass that I saw a copy of it at a newspaper stand in Fulton street, Brooklyn. I got it, looked into it with wonder, and felt that here was something that touched the depths of my humanity. Since then you have grown before me, grown around me, and grown into me.

I expected certainly to go down to Camden last fall to see you. But something prevented. And, in time, I saw in the papers that you had recovered. The New Year took me into a new field of action among the miserables. Oh, what scenes of human horror were to be found in this city last winter. I cannot tell you how much I was engaged, or all I did for three months. I must waittill I see you to tell you about these things. [See indexical note p024.3] I have been going toward social radicalism of late years, and appeared here at the Academy of Music lately as President and orator of the Rochefort meeting. Now I would like to see you, in order to temper my heart, and expand my narrowness.

How absurd it is to suppose that there is any ailment in the brain of a man who can generate the poem of the Universal. [See indexical note p025.1] I would parody Lincoln and say that such kind of ailment ought to spread.

My beloved Walt. Tell me if you would like me to come to see you, and perhaps I can do so within a few weeks.

Yours always, John Swinton.I quoted W. that phrase from Swinton's letter: "I have been going toward social radicalism of late years." "Yes," said W., "I remember it. Are we not all going that way or already gone?"

I picked up a stained piece of paper from under my heel and read it, looking at W. rather quizzically. [See indexical note p025.2] "What is it?" he asked. I handed it to him. He pushed his glasses down over his eyes and read it. "That's old and kind o' violent—don't you think—for me? Yet I don't know but it still holds good." I took it out of the hand with which he reached it back to me. "Put it among your curios" he said, "you'll have enough curios to start a Walt Whitman museum some day." The note is below:

[See indexical note p025.3] "Go on, my dear Americans, whip your horses to the utmost—Excitement; money! politics!—open all your valves and let her go—going, whirl with the rest—you will soon get under such momentum you can't stop if you would. Only make provision betimes, old States and new States, for several thousand insane asylums. You are in a fair way to create a nation of lunatics."

Some neighbor had sent W. a plate of doughnuts. [See indexical note p025.4] He put four of them in a paper bag and gave them to me for my mother. "Tell her they are not doughnuts—tell her they are love."

Wednesday, April 11, 1888.

[See indexical note p026.1] A hospital talk with W. led him to speak of a letter he had just received from a western man, now prosperous, who had as a soldier been nursed by W. and was offering to send money, "with love and out of my great surplus." W. was visibly touched. We had a fine hour together, W. full of reminiscence. "I got lots of help those days from noble people all over the North—especially from women." He stopped and pushed his forefinger among some papers on the round top, drawing forth an old yellow envelope, unstamped, which he shoved over toward me. [See indexical note p026.2] "That was a great woman." I saw that the letter was addressed in his hand to "Hannah E. Stevenson 86 Temple st, Boston Mass." This memorandum was made on the envelope: "sent Oct. 8, '63." "That," he explained, "was the rough draft. Take it along: it will give you a little look in on the sort of work I had to do those days." The letter is given in full.

Washington October 8 1863 Dear friend

[See indexical note p026.3] Your letter was received, enclosing one from Mary Wigglesworth with $30 from herself and her sisters Jane and Anne—As I happened stopping at one of the hospitals last night Miss Lowe just from Boston came to me and handed me the letters—My friend you must convey the blessings of the poor young men around me here, many amid deepest afflictions not of body only but of soul, to your friends Mary, Jane, and Anne Wigglesworth. Their and all contributions shall be sacredly used among them. I find more and more how a little money rightly directed, the exact thing at the exact moment, goes a great ways. [See indexical note p026.4] To make gifts comfort and truly nourish these American soldiers, so full of manly independence, is required the spirit of love and boundless brotherly tenderness, hand in hand with greatest tact. I do not find any lack in the store houses, nor eager willingness of the North to unlock them for the

A Stray Scrap of Whitman's Manuscript

soldiers—but sadly everywhere a lack of fittest hands to apply, and of just the right thing in just the right measure, and of all being vivified by the spirit I have mentioned—Say to the sisters Mary and Jane and Anne Wigglesworth, and to your own sister Margaret, that as I feel it a privilege myself to be doing a part among these things, I know well enough the like privilege must be sweet to them, to their compassionate and sisterly souls, and need indeed few thanks, and only ask its being put to best use, what they feel to give among sick and wounded. [See indexical note p027.1] —I have received L. B. Russell's letter and contribution by same hand, and shall try to write to him to-morrow—

A Stray Scrap of Whitman's Manuscript

soldiers—but sadly everywhere a lack of fittest hands to apply, and of just the right thing in just the right measure, and of all being vivified by the spirit I have mentioned—Say to the sisters Mary and Jane and Anne Wigglesworth, and to your own sister Margaret, that as I feel it a privilege myself to be doing a part among these things, I know well enough the like privilege must be sweet to them, to their compassionate and sisterly souls, and need indeed few thanks, and only ask its being put to best use, what they feel to give among sick and wounded. [See indexical note p027.1] —I have received L. B. Russell's letter and contribution by same hand, and shall try to write to him to-morrow—

Address Care Major Hapgood Paymaster U S A

cor 15th and F St Washington D C

Thursday, April 12, 1888.

W. sometimes has what he calls "house-cleaning days." [See indexical note p027.2] He puts aside some waste for me on these occasions. I always take along what he gives me. I know what will be its ultimate value as biographical material. He rarely or never takes that into account. For instance today he said: "I would burn such stuff up—or tear it up—anything to get it out of the road." He laughed in handing me three letters done up in a string. "They are all declinations of poems," he remarked: "from different men at different times.' [See indexical note p027.3] Then after a pause: "These editorial dictators have a right to dictate: they know what their magazines are made for. I notice that we all get cranky about them when they say 'No, thank you,' but after all somebody has got to decide: I am sure I never have felt sore about any negative experience I have had, and I have had plenty of it—yes, more that than the other—mostly that, in fact. [See indexical note p027.4] But take these letters—it is interesting to read the reasons they give for saying no. Bret Harte has become considerably more famous since those days: I used to think he was one of our men, or about to be—destined for the biggest real work: but somehow when he went to London the best American in him was left behind and lost."

Rooms of the Overland Monthly, San Francisco, Apr. 13th, 1870. My dear sir, [See indexical note p028.1]I fear that the Passage to India is a poem too long and too abstract for the hasty and the material minded readers of the O.M.

With many thanks, I am,

Your obt svt F. Bret Harte, Ed. O.M. Harper & Brothers' Editorial Rooms, Franklin Square, New York, June 8, 1885. My dear Whitman,[See indexical note p028.2] The Voice of the Rain does not tempt me, and I return it herewith with thanks.

Yours ever, &c. H. M. Alden. The Nineteenth Century, 1 Paternoster Square, London, E.C., May 19th, 1887. My dear Sir: [See indexical note p028.3]I greatly regret being unable to avail myself of the Poems November Boughs which you so kindly sent me with your note dated May 2d. In order not to put you to inconvenience by delay, I return them at once enclosed herewith. With very many thanks for your kind thought of me I remain

Yours very truly James Knowles.Friday, April 13, 1888.

[See indexical note p028.4] "This," said W., handing me an old O'Connor letter, "this will give you some more of the Osgood history: the whole history of the Osgood affair will, I suppose, never come out, but one thing and another adds light to it as time goes on. I see more and more that it was not Walt Whitman who was hurt by Osgood; it was rather Osgood who hurt himself. I guess some of our fellows made a good deal too much fuss about it all: we might have rested on our case and let the other side do the fussing. [See indexical note p029.1] However, no one could say how much such tilts as O'Connor has always been having for the Leaves may not have aided in showing the world that the natural laws were on our side." After reading the letter I asked W.: "Do you accept the whole Bacon proposition, too?" "Not the whole of it: I go so far as to anti Shakespeare: I do not know about the rest. I am impressed with the arguments but am not myself enough scholar to go with the critics into any thorough examination of the evidences."

[See indexical note p029.2] I have long wanted to write to you, but have been shockingly crowded down with work, and I have nearly forty letters unanswered. Your postal of Monday last came duly. Also the Springfield Republican. How deliciously like my old friend Henry Peterson is that critical exegesis on your lines! I shall certainly send it to Bucke that he may be convinced of the error of his ways by it, as I have of mine!

Your poem about the Arctic snow-bird is beautiful. I send a slip from the Washington Hatchet to let you see your article on Shakespeare reproduced. Did I tell you (probably not) about getting a letter from Mr. Gibson, the Librarian of the Shakespeare Memorial Library at Stratford-on-Avon? [See indexical note p029.3] This is a gorgeous stone building, all carved and paneled oak inside, containing a library, a reading room, a grand hall, a museum of Shakespeare memorials, etc. The librarian wrote me, very liberally asking me to send to the Library anything I had written in favor of the Baconian theory, saying that the management wished to give house-room to anything related to the subject (fact is, those fellows over there are beginning to feel the force of the Baconian claim. It is a sign of the rising of the tide, and ten years ago such a request would not have been made.) I at once sent Mr. Gibson a copy of Bucke's book, writing on the fly-leaf— [See indexical note p030.1] "To the Stratford Memorial Library," together with this line, a sort of twistification of a line from Sophocles, "May the truth prevail!" In December last, I got a very polite and cordial acknowledgement from the librarian, in which he says: 'Many thanks for your kind remembrance of my letter and the welcome gift of the life of Walt Whitman, in which is included your letter to Dr. R. M. Bucke, referring to the Bacon and Shakespeare controversy, which renders the volume admissible to our library. I am glad to handle the volume and hope, ere a few days are over, to become better acquainted with the personal history of your great American Poet. The beautiful portrait of the Poet in 1880, to Chapter 2, is exquisite and adds much to our interest in reading his life. His poems are not so well known here as Bryant, Longfellow or Whittier, but they are gradually becoming better appreciated as they are studied. Of all the American poets Longfellow has the widest popularity, and his writings are better known than most of the English poets.'... So, you see, there you are lodged in the great Memorial at Stratford, close by Shakespeare's tomb.

I must tell you something funny. You know what I say in Bucke's book, page 91, about Dr. Kuno Fischer, ending with the observation that it is strange that having gone so far in seeing the Shakespearean connection with Bacon, he did not take the step that would seem inevitable. [See indexical note p030.2] Now comes the news that he has taken the inevitable step! Mrs. Pott writes me from London that he has come out squarely for the Baconian theory, and was to give a course of lectures on the subject this winter at the University of Heidelberg, where he is professor of philosophy and literature. So it would seem my words were prophetic. This is the most important accession to the theory yet made. Dr. Fischer is a very eminent man, widely known in Europe, and his advocacy will carry weight. There is a string of eminent German professors who have also come out for the cause, notably among whom is Dr. Karl Müller of Stuttgart. [See indexical note p031.1] He has translated our Appleton Morgan's Shakespeare Myth into German, and it will have the honor of being published by the great house of Tauchnitz. All this will be gall and wormwood to the literary gang here who, for years, in their effort to suppress us, have acted like the Dragon of Wantley in his dying moments.

Mrs. Pott writes me that the cause grows daily in England, a number of old scholars, not publicly known, but men of learning and judgment, having given their adhesion, and the young men at Oxford and Cambridge also joining in numbers, are getting ready to fight for Bacon. Hooray! Meanwhile, I bide my time in the cellar.

Here is something decidedly rich which I heard a couple of weeks since, and tell you in confidence, so as not to compromise the narrator. It is extremely creamy. You know, or you do not know, that Osgood and Co., besides being publishers, also run the Heliotype Company, which does beautiful work in that line, in reproducing maps, plans, engravings, illustrations, etc. They have an office here and their agent is a Boston man, a very nice fellow, named Coolidge. [See indexical note p031.2] I am interested in a little enterprise in his line which brings me into connection with him. The other day I was in his office, and in chatting, referring to a beautifully published life of Home sweet Home Payne by the firm, I remarked that Osgood got out books in splendid style. Coolidge assented, but somewhat wistfully. "Why," said I, "don't you think so?" "O yes," he hastily answered, "but"—"But what?"—I asked, laughing. "Well," said Coolidge slowly, after a pause, "Osgood's a good fellow, and we all like him, but I'm afraid, as a publisher, he's going down." "Going down!" I repeated. [See indexical note p032.1] "Why how's that?" "Well," returned Coolidge, "I mean that he's losing his grip." "Losing his grip as a publisher!" I exclaimed: "Why, Coolidge, how has that happened?" "Well," he returned; then after a long pause, he continued briskly, "Did you ever hear of a man named Walt Whitman, who wrote a book called Leaves of Grass?" I admitted that I had heard of this man, and of his book. Then he went on to tell me, very circumstantially, that Osgood had solicited the publication of the book, got it out in good style, and was selling it right along, when the District Attorney threatened him with prosecution, etc., etc., (you and I know all this), when he got scared, broke his contract and stopped the publication. "What an infernal fool!" I exclaimed, just here. "Fool!" returned Coolidge. "I should say so! Why that was his chance! He ought to have told the District Attorney to go to hell, publicly defied him, and set all his presses to work. He'd have sold a hundred thousand copies in a month, and nothing could have been done to him." Then he went on to tell me that the affair made a great buzz, that Osgood was universally condemned for his cowardice, and thought to have acted dishonorably, that in consequence a blight fell upon him, and that he had lost his grip as a publisher for the present, and might be going down. [See indexical note p032.2] "If he does go down," concluded Coolidge, "it will be because of his conduct towards Walt Whitman."

Such is the outline of what Coolidge said, and considering that it was told me as to one who knew nothing of the matter, and by an intimate agent of the house, you may imagine my satisfaction. It was a real comfort to know that although we got so little support in the matter from "the organs of public opinion," there was a public feeling broad and deep enough to put the brand upon the miserable peddler who did this mean wrong. I rejoiced exceedingly to have learned it.

Isn't it a sweet sequel? Don't let Scovel print it (as the divvle did my note to him—wasn't I astonished!) for I wouldn't have Coolidge injured in Osgood's regard for the world, though I wouldn't care a continental how widely it was known that a blight had fallen upon Osgood for his treatment of you, provided the news came without a source being specified.

Gosse's visit to you, and his kind and respectful words, inexpressibly gratified me. [See indexical note p033.1] What gave it all point was that he had been fêted to the very top by the literati and aristocracy everywhere in this country, and I "phansy their pheelinks," in Yellowplush phrase, in contemplating the tableau.

But I must break off. I wonder if my life-saving career draws to an end. March fourth comes near. Despite the terrible routine of the office work, so wearying and confining, I am deeply interested in the noble work of the service, and should be sorry to leave it. I think, however, the pressure for Kimball's place and mine will be terribly urgent, and already we hear of many aspirants. Our successors will never do what we have done—fill the stations with the best professionals, no matter what their politics, and so make the life-saving work part of the National glory. Well, we'll see what Cleveland will do. [See indexical note p033.2] What a chance he has generally to break down the infernal spoils system!

I have a fine picture of Bacon, after Vandyck, which I am going to send you soon.

Good bye, Faithfully, W. D. O'Connor.As I was putting up the letter W. remarked: "William is always a towering force—he always comes down on you like an avalanche: his enemies are weak in his hate, his friends are strong in his love. William should have been—well, what shouldn't he have been? [See indexical note p033.3] He was afire, afire, like genius." Referring to Gosse's visit: "I have a letter here somewhere in which Gosse announced that he would come. I can't put my hands on it just now."

Saturday, April 14, 1888.

[See indexical note p034.1] W. is not insensible to professional applause, but he is emotionally most moved by the accessions of obscure persons who have no axes to grind and are not bothered by the pros and cons with which culture is apt to wear itself out. He spoke of this today and as illustrating his notion gave me a letter from his table and called my attention to a note he had made on the envelope: "from a lady—a stranger—Washington—1870 (a letter to comfort a fellow and brace him up)." He waited while I read.

Sir.

[See indexical note p034.2] You have had many tributes from the learned and great of Europe and America, yet you will not despise that of a simple, honest woman who writes to thank you, in all sincerity, for those Leaves of Grass from which her soul has drawn such health, freshness, and aroma. I visited Washington for the first time this May, the guest of Mrs. Schwartz (who one night in passing off the platform of a car gave you a rose). I was compelled to [take] many car rides in my transit to "the city." On car No. 14 I encountered you more than once. Your face, which I chose to think a fac simile of the grand old patriarch's, Abraham, attracted me. Through Mr. Devlin, from Mr. Doyle, I was allowed to read your—I prefer saying—I was permitted a long look into the wonderful mirror of your creation, where I saw the reflex of your soul, and felt the influence of your divining power. [See indexical note p034.3] Mr. O'Connor's manly, eloquent, but most unnecessary vindication of your purity was also given me.

Only themselves understand themselves and the like of themselves,

As souls only understand souls.

I needed no one to translate for me the language of yours, written so plainly in every line and furrow of your face, and revealed to the world in the many gracious deeds of love to your kind.

I closed your book revelation, a wiser and more thoughtful woman than when from idle curiosity I first opened it at the very stanza, Perfections, which I have just quoted. [See indexical note p035.1] Life held grander possibilities to me from that hour, and the mission of a soul born into this world to love, influence, and suffer, was invested with profounder responsibilities.

[See indexical note p035.2] To whoever is granted the power to make another long for Truth for its own beautiful sake; love the lowly and oppressed for the sake of the divinity spark which is in each human body and see in Nature the heart of the great Mother-God who conceived and gave it birth—to such an one there is a debt due of allegiance and profound gratitude.

I thank you Sir, with all my heart, and pray for you the abiding Presence and hourly comfort of the divine Pure in Heart whom you worship.

I need make no apology for this note. You will not misunderstand it. I go to my home in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, tomorrow. I may never again chance to see you, but you will believe, nevertheless, that I will wish for you—and teach others to do the same—a long earth life of usefulness, and an eternity of appreciation and renown.

Reverently yours Mrs. Nellie Eyster.When I was through he asked: "What do you think of that? Would a thousand dollar bill do you as much good as that? [See indexical note p035.3] I think I never got a letter that went straighter to what it was aimed for: it's better than getting medals from a king or pensions from Congress."

W. had been burning some old manuscripts today. A piece had dribbled at the foot of the stove. I picked it up. "Shall I take it?" "If you choose—but what's the use." He laughed.

[See indexical note p036.1] "Eighty millions of Tartars may shave the top of the head from Comparison to Self-Esteem, and so on down to the ears; and this may be done for thirty centuries, and be one of the institutions of the Empire.—But if a man appears at the end of that time in whose eyes the custom is unnatural and therefore ungraceful, this man will be none the less right because he is denied by a hundred generations, whose coronal fronts were well scraped, and whose pig tails hung down behind."

Above this note, which was of an old period, probably the fifties (the ink was much faded) W. had written in pencil: "Japanese women (mothers) shave their eyebrows."

Sunday, April 15, 1888.

To W.'s in the forenoon. "I'm going up to Tom's for tea—you will be there?" He was trying on a new red tie. "Red has life in it—our men mostly look like funerals, undertakers: they set about to dress as gloomy as they can."