Thursday, June 21, 1888.

Thursday, June 21, 1888.

Eight o'clock, evening. W. up out of bed—better by a good deal than yesterday. Eats more comfortably. Feels sounder. Says he is not confident "beyond the immediate [Begin page 362] hour." Repeatedly dwells upon his "loss of grip"—"grip" the constant word: "grip" on Hicks, "grip" on proofs, "grip" on this and that. [See indexical note p362.1] "I do not seem to have the mental grasp: I find my mind unwilling or unable to apply itself to the proofs, the manuscripts, as it should, methodically, systematically: I am only imperceptibly if at all regaining my strength in that respect from day to day." I reminded him of what he said yesterday—that he was determined to live. "Yes," he replied, "I do not forget that—I am doing all I can to buoy myself up, to move back or ahead on secure ground again."

W. had returned yesterday's proofs through Baker today. [See indexical note p362.2] I kicked. I said I ought to do all those errands myself in order to keep a supervising eye on our affairs at Ferguson's. I said to him: "If I am to work with you it must be on this condition." He at once came down. "I see it was a mistake—it shall not occur again—we will lose rather than gain if I do anything to confuse you. You are quite right. I wish you would go to Ferguson's the first thing in the morning and see what I did with the returned pages. I know page 37 is lame and weak—that it contains some faltering lines—but I guess it must go as it is. Anyway, we will have a chance to get at it again."

Received a note today from Bucke. [See indexical note p362.3] Osler not over though Baker had been to Philadelphia to report. This is the first day W. has expressed any feeling of discomfort on account of the heat. Was mentally very clear, however. "Your father has been in—we had a slight talk: he is the most learned man in German literature I have ever met—full of enthusiasm, too—still a young man in the real sense." "In that sense you yourself are young enough." "I hope so," said W. fervently: "when I get old in that sense I want to step out of the way."

[See indexical note p362.4] In talking of O'Connor W. asked me if I knew that O'Connor "was hypochondriacal?" adding: "Well—he is a suf- [Begin page 363]ferer that way: he experiences certain periods of poignant depression, then long exemptions—regular returns of good and bad, seasons coming and going. [See indexical note p363.1] Do you know, Horace, William should have been an orator: all his Keltic bardic ancestry seems to set him afire for it. He would have made a great pleader: I do not think any audience could remain unsubdued, once William got going. He has the impetus of genius—there is always a wild current back of him pressing him on."

W. referred to Frederick Marvin, also, as "a consistent friend when consistent friends were none too many." [See indexical note p363.2] Then indulged a bit of self-characterization: "All my friends are more ardent in some respects than I am: for instance, I was never as much of an abolitionist as Marvin, O'Connor, and some of the others. [See indexical note p363.3] Phillips—all of them—all of them—thought slavery the one crying sin of the universe. I didn't—though I, too, thought it a crying sin. Phillips was true blue—I looked at him with a sort of awe: I never could quite lose the sense of other evils in this evil—I saw other evils that cried to me in perhaps even a louder voice: the labor evil, now, to speak of only one, which to this day has been steadily growing worse, worse, worse. I did not quarrel with their main contention but with the emphasis with which they asserted their particular idea. [See indexical note p363.4] Some of the fellows were almost as hot with me as with slavery just because I wouldn't go into tantrums on the subject: they said I might just as well be on the other side—which was, of course, not true: I never lost any opportunity to make it plain where I stood but I did not concentrate all my moral fire on the same spot." [See indexical note p363.5] W. "dissents from partisanship whatever its name or form," for, said he this evening, "after the best the partisan will say something better will be said by the man."

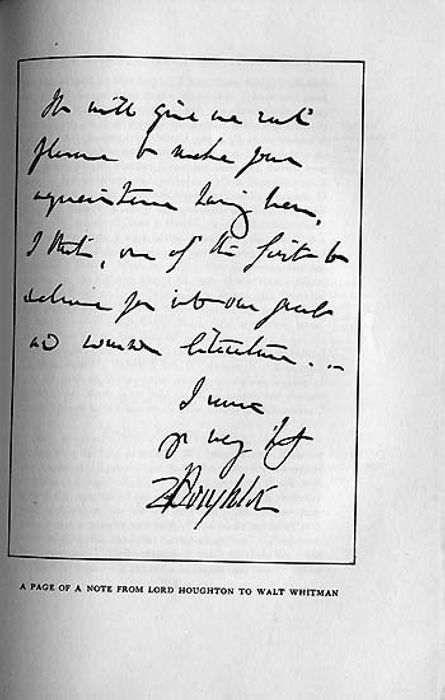

W. sat fanning himself during our talk, and was mentally clearer, I think, than for several days. He clouds up. He [Begin page 364] never stays in the cloud. The peculiarity of his trouble is this—it sometimes ends his thinking short, mars his sentences, mixes his tenses, makes him inconsecutive. As he says himself: "The right word won't answer—my tongue gets unruly—I lose my cues. [See indexical note p364.1] I mix up badly—but I inevitably come back again." Anent the Miller letter W. produced a Lord Houghton note of the same month and year. W. laughed over the writing. "It is as bad a hand as Miller's or worse." He was rather surprised when I read it outright. [See indexical note p364.2] "Bravo! bravo!" he said—and then asked: "What shall be your reward?" I thought a minute and said: "Give me the letter." W. without hesitation saying: "Is that all you ask? Why certainly—take it." This is what I read:

Brevoort House, New York, Sept. 29th. Dear Mr. Whitman,[See indexical note p364.3] I was only in Philadelphia for a few hours, but I propose to return there for some days the end of next month or the beginning of November. It will give me real pleasure to make your acquaintance having been, I think, one of the first to welcome you into our great old world literature.

I remainYours very truly Houghton.

[See indexical note p364.4] W. had written on the envelope: "Sept. 27, '75 from Lord Houghton." I asked W.: "Did he come?"

"Yes—although I understand that they tried all round, in Boston, in New York, 'most everywhere, to induce him not to come—to convince him that I was not entitled to the attention he proposed to offer me. This was the very first thing he told me when we met—how solidly the literary crowd was arrayed against me. I asked him: 'What does that signify?' He laughed and said: 'It is a compliment—you should feel honored.'" W. was quiet for a few minutes and returned

[Begin page figure-26]

[Begin page 365] to the subject in this way: I have been through all that mortal flesh need have to test its fidelity: I have had good enemies and bad enemies—and friends—friends false, friends true (is there a worse enemy than a humbug friend?)—you know more or less who I mean. [See indexical note p365.1] I often wonder if I have survived—whether this is a real me, sitting here talking with you, or whether I was not dead and buried long ago." He laughed and added: "What nonsense such speculation is! It interferes with the healthy business of life." I picked up a slip of paper from the floor under my feet. W. asked: "What is that?" I quoted his own line: "Wherever I go I find letters from God dropped," &c. He smiled: "Read it—my eyes are no good."

[See indexical note p365.2] The sheet contained this: "Mem for Life. The Macready riot occurred on the night of May 10th 1849—I was then publishing 'the Freeman' cor Middagh & Fulton sts. Brooklyn had returned from N.O." W. recognized the note. "Yes: I have used it somewhere. Such little reminders sometimes open a very big door of reminiscence—but I am no good tonight even for that, even to talk—to look behind or look ahead." When I left W. remarked: You must use all your diplomacy with Ferguson—we are lagging at a sad pace: there is no help for it, of course, but he naturally objects to us when we clog the wheels of his business."

[Begin page 365] to the subject in this way: I have been through all that mortal flesh need have to test its fidelity: I have had good enemies and bad enemies—and friends—friends false, friends true (is there a worse enemy than a humbug friend?)—you know more or less who I mean. [See indexical note p365.1] I often wonder if I have survived—whether this is a real me, sitting here talking with you, or whether I was not dead and buried long ago." He laughed and added: "What nonsense such speculation is! It interferes with the healthy business of life." I picked up a slip of paper from the floor under my feet. W. asked: "What is that?" I quoted his own line: "Wherever I go I find letters from God dropped," &c. He smiled: "Read it—my eyes are no good."

[See indexical note p365.2] The sheet contained this: "Mem for Life. The Macready riot occurred on the night of May 10th 1849—I was then publishing 'the Freeman' cor Middagh & Fulton sts. Brooklyn had returned from N.O." W. recognized the note. "Yes: I have used it somewhere. Such little reminders sometimes open a very big door of reminiscence—but I am no good tonight even for that, even to talk—to look behind or look ahead." When I left W. remarked: You must use all your diplomacy with Ferguson—we are lagging at a sad pace: there is no help for it, of course, but he naturally objects to us when we clog the wheels of his business."