Thursday, July 5, 1888.

Thursday, July 5, 1888.

[See indexical note p422.2] Eight o'clock, evening, when I went to W.'s. On his bed. There the whole day. Pulse slower. "I've had a bad day—a miserable day—all the symptoms of another spell—everything but the spell itself." Then stopped and added: "I suppose you get disgusted coming here every day to hear my perpetual whine—my everlasting growl." No. Only anxious at times. "Thank you, boy: I am glad it's no worse than that. After all I do not kick—I am willing to take what comes—death or life—half life, half death—everything. I clearly perceive that I shall never get back where I was—I have slipped down a notch or two. But I don't care. [See indexical note p422.3] My only concern is for the work—the book. I don't want to sink—drown—before the book is out." Yet he also said: "I am determined to make a break for getting down stairs before long. Doctor Bucke writes about it—says, don't go: but I am going to break out of bond—make the effort—whatever results." "But how can you do it now lame as you are?" "Did I say now?" Laughed. "That was brag. I didn't mean it. Some day."

Gave him proofs. Addressed two letters for him. "Both my fingers and my memory gave out." Very calm. Kindly,

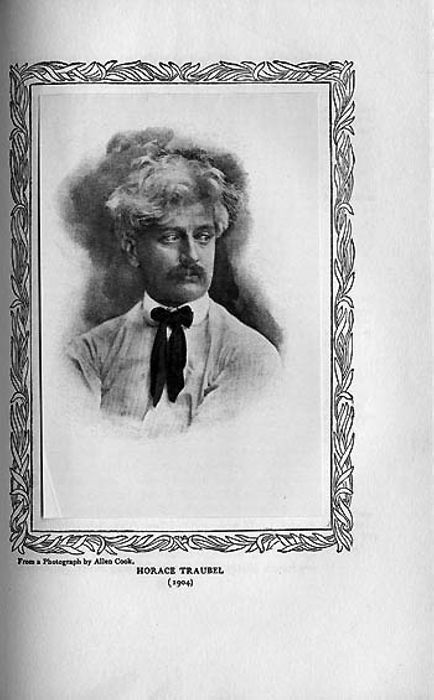

Horace Traubel (1904)

quiet, serene, undisturbed. "I have made up my mind not to worry—not to let even the worst upset me—not to look with dread upon anything. [See indexical note p423.1] I like to think it over and over and over again with Epictetus—I have often said it to Doctor Bucke and to you, too—'What is good for thee, O Nature, is good for me!' That is the foundation on which I build—it is the source of my great peace." Was rather playful about his disturbed stomach. "It is in a bad enough way, but let it have its turn—I have only to be quiet and wait."

[See indexical note p423.2] Mrs. Davis came in. W. asked: "Well, Mary, what's the news?" Mrs. Davis replied: "Mrs. Cleveland has stopped wearing a bustle—now bustles are no longer the thing!" W. took up the subject in the same playful vein: "I thought I heard some boys crying 'extra' on the street. That must have been it!

Horace Traubel (1904)

quiet, serene, undisturbed. "I have made up my mind not to worry—not to let even the worst upset me—not to look with dread upon anything. [See indexical note p423.1] I like to think it over and over and over again with Epictetus—I have often said it to Doctor Bucke and to you, too—'What is good for thee, O Nature, is good for me!' That is the foundation on which I build—it is the source of my great peace." Was rather playful about his disturbed stomach. "It is in a bad enough way, but let it have its turn—I have only to be quiet and wait."

[See indexical note p423.2] Mrs. Davis came in. W. asked: "Well, Mary, what's the news?" Mrs. Davis replied: "Mrs. Cleveland has stopped wearing a bustle—now bustles are no longer the thing!" W. took up the subject in the same playful vein: "I thought I heard some boys crying 'extra' on the street. That must have been it!

[See indexical note p423.3] W. asked me a question in this way: "I have been thinking a good deal about Sands at Seventy today—a good deal. I want to know whether you feel that they will be out of place in Leaves of Grass—not integral—too distinctly different in character to connect with the story? Bucke seems pleased and satisfied—thoroughly so: do you? Has Tom said anything to you about it? How do these poems stand in relation to the whole? [See indexical note p423.4] Have they peculiarities decided enough to isolate them?—do they in any way, the slightest way, contradict the general tenor of the book?—what I have tried to say in the Leaves so far—what has been aimed at? I am curious to know what you feel about all that—to have you tell me." I spoke of the "dignity" of the Sands. He caught up the word at once. "Dignity, did you say? Is it dignity? [See indexical note p423.5] I hope so—yes, I hope so. I remember well how one of my noblest, best friends—one of my wisest, cutest, profoundest, most candid critics—how Mrs. Gilchrist, even to the last, insisted that Leaves of Grass was not the mouthpiece of parlors, refinements—no—but the language of strength, power, passion, intensity, absorption, sincerity— that Leaves of Grass was no book for disease—for smallpox, rheumatism, yellow fever, scrofula—but was eminently and before all a book of health, the open air." [See indexical note p424.1] After a pause: "But I only throw out my question for you to chew on: I want your opinion. Take it with you and see what comes of turning it over—of seeing it all sides." Then he smiled and clenched his fist and raised his arm from the bed. "You know, boy, we must face all that and more: we must not be afraid of the worst—indeed, we must invite the worst—must bear all, brave all, and, coming to the test, throw or be thrown by it. [See indexical note p424.2] The question has come back to me in fifty different forms as I lie here footing up my accounts with the Almighty!"

In discussing some points involving the sale of November Boughs W. suddenly said to me: "And now that that point is up, Horace, I want to say to you that I rely upon you when the occasion arises to bear testimony to Dave McKay's fair dealing and general good will as toward me. Several of my friends have been to me lately and said: 'You'll have to watch McKay—he's foxy—he'll do you up.' I asked them: 'Why do you suspect Dave more than others—pick him out for criticism?' They said: 'We don't—he is a publisher: that is enough: all publishers do it.' Which of course sets Dave free. [See indexical note p424.3] I believe Dave is friendly to me—not friendly alone as a publisher but as a man—treats me squarely. By and by that will come up and I want you to speak for me on that point. I hate to be suspecting people anyway. I know Dave's weaknesses (and he knows mine, no doubt, and that's how we're square!) but have been able in the main to sail with him one trip after another on the most amiable terms. [See indexical note p424.4] I have real admiration for Dave—he has a sort of Napoleonic directness of purpose—has immense energy—has made himself very strong by self-discipline. [See indexical note p424.5] Did you ever hear Dave go off about Dick Worthington? He is very sore on Holy Dick—more sore than I am—would push him to the wall if I'd let him."

[See indexical note p425.1] W. alluded to the superior presswork of English books, producing a book recently sent him by Symonds in evidence. "Anyhow they seem to be more conscientious over there in the trades—not in printing only but from the top down." Bucke reports that the English edition sent him by W. has not arrived. W. wondered if he "had misdirected it." "My memory is shamefully abusing my faith nowadays." [See indexical note p425.2] Put an old Roden Noel note into my hand from under the pillow. "I always bear you in mind: I am getting together such things as have ceased to be of use to me—which may be of practical service to you. [See indexical note p425.3] They all go to make up a story. A story? Yes. But will the world ever wish to hear it?—ever be willing to listen while you tell it? Noel was consistently friendly—never spared himself—confessed the faith wherever he was—everywhere—on the streets, in swell parlors—with the fashionables—everywhere."

Maybury, Woking Station, Surrey, England, Nov. 1871. My dear sir,[See indexical note p425.4] I send by this mail the second part of my study of your works. I hope I may not unintentionally have misrepresented you, but if I could be one of the means of drawing more general attention to your great works than they have yet received in this country, I believe I should have done something worth the doing.

May I venture to hope I may have a line from yourself when you have time? [See indexical note p425.5] And may I again repeat the hope I expressed to you in a former note when I sent you my own vol. of poems—the first—and which I am rather ashamed of now—on account of its Byronism—and too much leaven of aristocracy which is born with me—that you will not visit this country without coming to us?

I want to get hold of the American ed. of your work—which was lent me by Buchanan, but I understand it is difficult to procure.

The proclamation of comradeship seems to me the grandest and most momentous fact in your work and I heartily thank you for it.

Yours with much respect and in all sincerity, Roden Noel.[See indexical note p426.1] After I had read this note W. commented upon it in this way: "The fact remains, that the English are still ahead—that I have made no gains this side to equal my victories across the sea—that the crowd on the other side is in the main willing to give me a hearing—that the crowd this side is in the main dubious about me, if not actually antagonistic." I put in: "But who cares? Do you?" [See indexical note p426.2] "No—I do not: I take what comes. I think I must sometimes seem to take it more seriously than I do." "Besides maybe the English crowd is wrong and the American crowd is right. Maybe you're after all no good!" "That's so: I wake up at night sometimes for thinking of it!" [See indexical note p426.3] Had W. read the Noel poems? "Some, a few—very few: they are rather good—show some skill in architecture—they are well built: but Noel will scarcely last out."

No more tonight. W. admonished me: "You must help me to keep up with Ferguson: he has had great patience. [See indexical note p426.4] I expected to be kicked out long ago. You must be a pretty good diplomat." I demurred. "It's not my diplomacy it's his respect for you." W. would not have it that way. "You say that—but I still believe it's your diplomacy." Said he had "Noel's book about somewhere." Did I care to look at it? Yes. "You shall have it." Left. [See indexical note p426.5] As I did so he called to me: "Kiss Anne Montgomerie for me even if it is not lawful; give my love to the boys: tell Lindell, at the ferry, that I often think of him, as I lie here—of his damned old fiddle—I wish I could hear him again: and then there are all the fellows about everywhere to write to—I must neglect them all: you must do what you can to get, keep, in touch with them, for your sake, for mine. In all this world there's nothing so precious—in all this world, nothing. Good night! Good night!"