Wednesday, July 11, 1888.

Wednesday, July 11, 1888.

[See indexical note p447.3] W. passed a good day. I went down in the evening towards eight. Some indigestion. On his bed. Stayed nearly an hour. Pretty communicative. I let him pursue his own fancies. Only nudged him with a word or two now and then. Likes to be let alone. Voice rather husky. Troubled some with words. Mind perfectly clear. "As for the indigestion—I do not mind it. Now that my mind has got back to good weather again I feel more or less satisfied. I am more sensitive to intelligent impressions, mentally speaking, and am almost comfortable physically. [See indexical note p447.4] This seems like a gain, though I must not brag. Down I may go again any time!"

[See indexical note p447.5] W.'s niece Jessie was here today. Letter from Bucke. Wrote cards to Bucke, O'Connor and Kennedy. Mrs. Kennedy sent him a box of roses. Mailed off two copies of L. of G. to purchasers—one in New York and one in St. Louis. With the former, for which he was paid five dollars, W. enclosed an autographed portrait. No word yet from Griffin. W. had undertaken to work on the Hicks matter but gave it up. "I am more and more persuaded that I can never work it out according to the original design—I do not seem to be able to stand the strain. [See indexical note p448.1] No doubt it will have to go in just as it is, taking its chances." Describing Bucke's philosophy with regard to handling the insane: "His method is peaceful, uncoercive, quiet, though always firm—rather persuasive than anything else. Bucke is without brag or bluster. It is beautiful to watch him at his work—to see how he can handle difficult people with such an easy manner. [See indexical note p448.2] Bucke is a man who enjoys being busy—likes to do things—is swift of execution—lucid, sure, decisive. Doctors are not in the main comfortable creatures to have around, but Bucke is helpful, confident, optimistic—has a way of buoying you up."

[See indexical note p448.3] W. said he could never "reconcile" himself to Thoreau's and Carlyle's treatment of the common man: "They stood about with a wall around them. I guess friendship is constitutional, or in great part so—you like cabbage or you don't and that's all there is about it. [See indexical note p448.4] I had a friend once, Haggerty: a Scotch-Irishman or something of that sort—a good-natured excellent fellow all through, who often used to say to me; 'Walt Whitman, I think the one thing for you to do is to go to Europe—to England, France, Germany—and see the new life there—see what you can make of it—get it, too, reflected in your work.'

[See indexical note p448.5] But I remember one evening, in the midst of a talk, when we were all having a good time (in Washington, during the war) he turned upon me and exclaimed suddenly: 'Walt Whitman, I used to think a trip to Europe—to England mainly—was what you needed but now I see that that would not do—would never do: it would not help you along in what you are trying to do—would rather hinder you: what you need is simply to stay here, stay, stay—and die here.'"

[See indexical note p448.6]

"I think Carlyle saw all the horrors of life in European centres of population—that

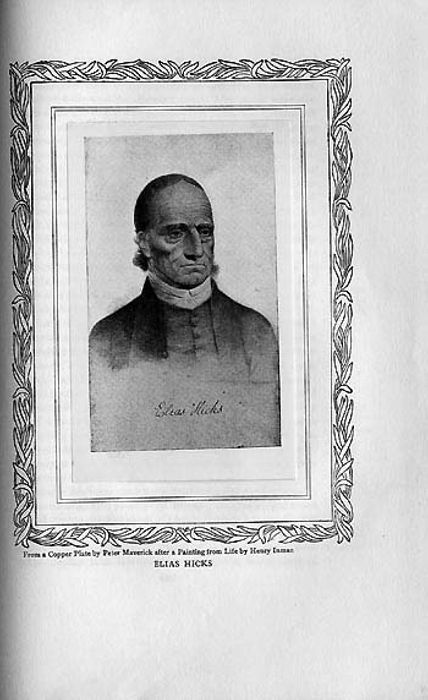

Elias Hicks

it made him mad, sour, disgruntled—put him in a hell of a humor with society. He was not a hater of the race—he wished it well—he spoke according to what he knew—but as he looked about and saw all the damnable evil, he grew depressed, seeing no way of escape. I think that explains one part of Carlyle—that and perhaps something constitutional."

[See indexical note p449.1] W. said that "Bucke has an immense faith in the people at large—immense—in civilization, in modern mechanical devices—miracles of power."

"Do you say that Bucke has more faith in the people than you have?"

"I think he has. I have seen in the later years of my life exemplifications of devilishness, venom, in the human critter which I could not have believed possible in my more exuberant youth—a great lump of bad with the good."

"That may be admitted. But you do not think there is enough bad to do away with the good?"

[See indexical note p449.2] This got him at once. He said almost sharply: "I do not—I do not: only I would not originally have believed it to be there. You know that I never admit that men have any troubles which they cannot eventually outgrow." He quoted from Tennyson's Northern Farmer, "the poor in a lump is bad."

"But then," I persisted, "suppose you refuse to consider them in a lump?" He laughed. "That's true—that's another point." I quoted an old woman, my friend, a Presbyterian, who said: "My head says hell but my heart won't say it at all."

[See indexical note p449.3]

"That's beautiful, beautiful," said W. Then: "Bucke is an optimist—thoroughly so, without qualification or compromise—so are you—but I could hardly call myself that in the strictest sense of the word."

Elias Hicks

it made him mad, sour, disgruntled—put him in a hell of a humor with society. He was not a hater of the race—he wished it well—he spoke according to what he knew—but as he looked about and saw all the damnable evil, he grew depressed, seeing no way of escape. I think that explains one part of Carlyle—that and perhaps something constitutional."

[See indexical note p449.1] W. said that "Bucke has an immense faith in the people at large—immense—in civilization, in modern mechanical devices—miracles of power."

"Do you say that Bucke has more faith in the people than you have?"

"I think he has. I have seen in the later years of my life exemplifications of devilishness, venom, in the human critter which I could not have believed possible in my more exuberant youth—a great lump of bad with the good."

"That may be admitted. But you do not think there is enough bad to do away with the good?"

[See indexical note p449.2] This got him at once. He said almost sharply: "I do not—I do not: only I would not originally have believed it to be there. You know that I never admit that men have any troubles which they cannot eventually outgrow." He quoted from Tennyson's Northern Farmer, "the poor in a lump is bad."

"But then," I persisted, "suppose you refuse to consider them in a lump?" He laughed. "That's true—that's another point." I quoted an old woman, my friend, a Presbyterian, who said: "My head says hell but my heart won't say it at all."

[See indexical note p449.3]

"That's beautiful, beautiful," said W. Then: "Bucke is an optimist—thoroughly so, without qualification or compromise—so are you—but I could hardly call myself that in the strictest sense of the word."

Cabot's Emerson contains a note from Burroughs describing a meeting with E. at West Point. W. greatly interested—had me repeat the story. [See indexical note p449.4] Then: "After I hear all that it sounds a little familiar. I think John may have told me about it." W. called my attention to a newspaper paragraph stating that Harrison once taught a Bible class of lawyers. "That seems very funny to me," he said: "too funny to be even laughed at—funny enough almost to be sad. Do you know, Horace, a tremendous deal of the public objection to Leaves of Grass came straight from the Sunday School? [See indexical note p450.1] From Sunday Schools and what makes Sunday Schools? The Sunday School has omitted virility from the list of its moral forces." I said to W.: "Anne Montgomerie says this is the Sunday School: 'I think so. Don't you? Yes.'" W. very heartily responded: "That's mighty good: very cute—it leaves nothing to be said." Paused and added: "It's really most capital." Repeating the formula aloud: "It is a complete picture. I must not forget it."

[See indexical note p450.2] W. gave me a Rhys letter to read, saying of it: "It is a noble letter—I am proud of it—proud of it not because it is addressed to me but because Rhys had the sort of soul which makes that sort of letter possible. And I entirely sympathize with what he says about the poor—the gospel of life for the poor—with his resentment as towards those who would make Leaves of Grass exclusive—keeping it as a choice morsel for the palates of the well-to-do. [See indexical note p450.3] You know we have often talked of bringing out cheap editions of special poems in this country. I have even spoken to Dave McKay about it though he is up in arms against the idea. I'll tell you what, Horace—if I pull out of this trouble we will produce a few small trial books—don't you think?—just to show where we stand. That is about the handsomest letter Rhys ever wrote me. They have sold a good many Whitman books, one kind or another, in England. [See indexical note p450.4] I never got anything of any account out of it—though I don't know as that matters much: the chief thing is, that the books get about." Then he added: "I read Rhys' letter over and over again today. Such a letter makes everything worth while—sickness, sorrow, even death: makes everything worth while."

59 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, London, S.W. 7th July, 1885. Dear Walt Whitman,[See indexical note p451.1] More than a month back I addressed a letter to you, which misfortune of one kind or another may have overtaken, or which you may not have had time or inclination to answer. It was referring to the scheme of a new edition of your Poems in England here, but I'm afraid was not clear enough as to the rights and reasons of such an edition, or the way it would be carried out. [See indexical note p451.2] In the letter I explained something of this, but not enough; and it was careless of me to do this and then expect you to reply to an insufficient proposal, when you must have already more to do in this way than can be easily compassed. For fear too that the letter never reached you at all, it will be better to state the whole matter afresh.

[See indexical note p451.3] A series of poets was last year begun by Walter Scott, the publisher, under the occasional editorship of my friend, Joseph Skipsey, poet and former coal-miner; (I have been a coal miner—a mining engineer that is—myself; hence the connection!) and in their list a month or two after my arrival in London as a student of life and letters this year, I saw rather to my astonishment your name amid the rest, and feeling that in some ways I had a special right and knowledge I ventured to write in, offering to prepare the vol. Skipsey's influence did the rest.

At first it seemed rather out of place to have your work in a series of this kind called, rather stupidly, The Canterbury Poets, and got up in a cheap and prettified fashion, with red lines, &c. [See indexical note p451.4] But afterwards it struck me that there might be gain in the end through it. Now I have succeeded in one hope: the publishers will give up the red lines and trivial design of cover. Next will be to have your Poems issued in a different shape—quite square I should like to have it—so as to give your long lines full play! And the very including of Leaves of Grass in a series like this gives them a chance of reaching people who would otherwise never see them. What I—and many young men like me, ardent believers in your poetic initiative—chiefly feel about this is, however, that an edition at a price which will put it in the reach of the poorest member of the great social democracy is a thing of imperative requirement. [See indexical note p452.1] You know what a fervid stir and impulse forward of Humanity there is today in certain quarters! [See indexical note p452.2] and I am sure you will be tremendously glad to help us here, in the very camp of the enemy, the stronghold of caste and aristocracy and all selfishness between rich and poor!

Some people want to class you as the property of a certain literary clique,—a rara avis, to be carefully kept out of sight of the uneducated mob as not able to understand and appreciate the peculiar qualities of your work. This does harm in many ways, and it would be a very good thing to make a fair trial of the despised mob. The price of Wilson & McCormick's edition—half a guinea—practically damns the popular circulation of the book, and gives color to the notion of its being a luxury only for the rich. [See indexical note p452.3] What we want then is an edition for the poor, and this proposed one at only a shilling would be within reach of every man willing and caring to read.

I did not know until a week or so back that Wilson & McCormick had any direct authorization for their edn, or should certainly have advised Walter Scott to communicate his intention to them. [See indexical note p452.4] Now someone has written on their behalf resenting—very naturally—his appearance in the field. But this difficulty might be easily settled by Scott paying, say ten guineas outright or a certain royalty per copy, to them on your account, if W. & McC. would not like a new contract with you by Scott. The fact of the new proposed edn being one of smaller scope [the vol. would not hold more than two-thirds of the poetry;] would no doubt weigh with them too, reference being clearly made to the complete works to which this would serve as a pilot for the time being, and increase the sale in the end.

[See indexical note p453.1] As for my own share, all I really care about is to procure a serviceable popular edition, giving all the help an earnest and enthusiastic sympathy can devise. On mere literary grounds I have very little claim, but I have a great love and desire to help the struggling mass of men, to be a true soldier in the War of liberation of Humanity. I should strive to just say what would best bring your Ideal to the hearts of such as the coal-miners and shepherds of the north—dear friends of mine many of them—many consciously, all unconsciously—and being a young man myself to make Leaves of Grass potent for comradeship and chivalry and manliness all through in the young men who are in the forefront today.

I feel very much inclined to say a good deal more about my hopes and ideals, but tonight perhaps it is better not. One thing though I must say a word about—how much in noblest knowledge and inspiration I have to thank you for, in life and religion and poetry and manhood, a debt it will not suffice to pay in words at all, but which some day you will see, I hope, may be fairly written off the score. [See indexical note p453.2] Meanwhile, receive the greeting of one more follower on this side the Atlantic,—very earnestly.

Any suggestions or directions as to the scheme and scope of the book I will thank you for most heartily; and will furnish fuller details as they are arranged.

Ernest Rhys.