Saturday, May 30, 1891

Saturday, May 30, 1891

Hurried up to Longaker's house, whence to Dooner's, where breakfasted with Bucke. The doctors interchanged views as to W.'s condition. (Bucke last night took views which I am sure he will have to revise: too favorable—W. flushed over his coming.) Thence to studio of Eakins (O'Donovan coming in after a

while). Interesting hour and a half there—talking about art and Whitman and various kindred affairs. Eakins sui generis. A strong type—lounging, easy, not a useless word—full of admiration of W. I asked both over to the dinner tomorrow—they will come. We reached W.'s at about one, rather than twelve, and found W. impatiently waiting—"I have been here for an hour." Mrs. Davis prepared our strawberries (we had been hungried and bought these on the street). Table in parlor—where we ate. After which, Warren going out and getting carriage, we went for our drive to the tomb (as prepared yesterday). W. very labored on the way down—and it was quite a long process to get him into the carriage. He joked about his lameness, asking, "How do I look? I must take care"—whispering—"that my shirt tail don't hang out." Bucke drove—Warren along—W. at once uttering his enjoyment of the fresh air—and from that time on being very conversational. We went direct to Harleigh, to the tomb, about the grounds, and home again. Much discussion by the way of the piece of land he proposes to buy—near Liberty Park. "I am aware of how women grow old, and people look on them as useless and in the way, and I am determined that Mary Davis, for one, shall be protected against that." And again, "Warrie, I feel to build two houses—one for Mary, one for me"—and at different places. "How would that do?"

"Look at the hill there—what a plot!" Or, "Why shouldn't I buy half a dozen lots somewhere about here? They can't cost much, and it wouldn't be bad, even as a matter of speculation." And so matters were argued—and sites—W. repeatedly protesting his seriousness and saying, "We must love the ground we tread upon and the friends who tread it." All along the road he saluted people—especially the children—many of whom regarded him with a sort of wonder—and some out of a recognition of the old days of his more frequent goings-forth. At the cemetery he called loudly into the lodge for Moore, who came out and whom W. asked about the progress of the tomb, to which we drove at

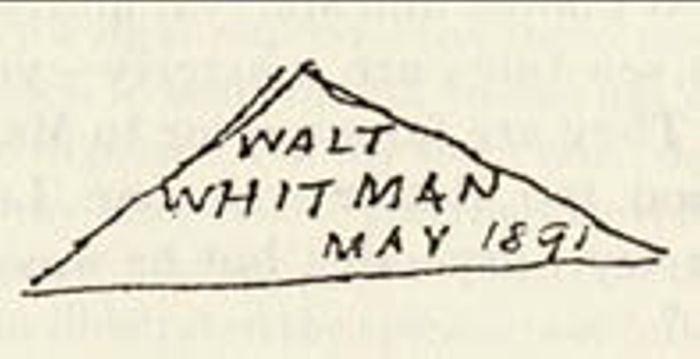

once, Moore coming down later on. The great, shaggy, massive, earth-big stones of the tomb impressive to imagination. The letters cut in front, this way:

Drawing of Whitman's tombstone design, reading, "Walt Whitman May 1891"

did not attract W., who admitted, "My first look is unfavorable—somehow, my printer's eye seems offended. I am not satisfied with it—yet cannot say why." Bucke and I immediately took ground against the date below, which—much turned over—was "ordered wiped out" by W. before we left. "You both vote against it, do you?" And at first he said, "Let it rest a day or two," finally however declaring, "Let it go—it might as well—it is an easy matter—let it go!"

Drawing of Whitman's tombstone design, reading, "Walt Whitman May 1891"

did not attract W., who admitted, "My first look is unfavorable—somehow, my printer's eye seems offended. I am not satisfied with it—yet cannot say why." Bucke and I immediately took ground against the date below, which—much turned over—was "ordered wiped out" by W. before we left. "You both vote against it, do you?" And at first he said, "Let it rest a day or two," finally however declaring, "Let it go—it might as well—it is an easy matter—let it go!"

W. was helped out of the carriage into the tomb, where he stood and described things as he intended them "and as now they really seem to be." Pointed to the three crypts to the north (four in each of two rows) and said, "Let this be understood"—pointing with his cane—"the first is to be my father's, the ultimate for my mother, and I am to be between." And to Moore, "Make a note of that—it may be upper or lower—either way—but that arrangement." Said he marvelled himself at the size and mass of the walls and door. One of the workmen said to me comically, "The more I think of it, the more I see that nothing else—nothing—would fit Walt Whitman." They told W. many "admirers" came along, but this excited his laughter and questions, "How—what—do they admire?" He pointed to the naked top of the hill. "You know, it was through Tom they gave me the lot—they expected me to select a spot there in the open—ostentatious—but I said, we'll go on a ways, drive on, drive down in the woods—and down we went, and when I got here I saw at once the lay of the land—'This will do—this is the spot'—and here we are!"

We talked about Cooper and Marryat and Scott. W. considered, "Cooper's sea-tales are masterly—you should read them, Maurice. They are far superior to Marryat's, though Marryat's are good, too. Better even than 'Leatherstocking.' Cooper could be dry—dry—dry, but he was a great master, too, none better."

He insisted on giving the men some money for "bread and beer" or "some lunch." Inquired of us what we felt as to the stability of the tomb, drove us about the grounds—marking its improvements, Cooper's Creek at the back, flowers, etc.—having Bucke drive us past the tomb on the way out, telling Moore at the gate again how thoroughly the work pleased him—talking thus with us the whole way home. Had the trip done him harm? "None at all—I am a bit dazed—but I would be that anyway—was before I started. But you remember Consuelo—the poor moments when she was like to succumb—when things all seemed black to her—against her—but she set her teeth together—she would not flunk—no, would not—not till the victory was won—no break—no sign to that outward staring, gaping, expectant world. And after the blare was over, oh! the weakness, horror, then. And I am Consuelo—determined to keep my head up, whatever betide." But later, when we reached 328, I helped Warren with W. who—indoors—literally dropt on the first chair—looked at me—said, "Well, here is Consuelo at last!" Here I left him—Bucke going to tea with us.

7:50 P.M. To W.'s again for a brief stay—no evil signs from the ride. All it had done was to convince both of W.'s great weakness—"goneness," was W.'s word. We talked about the morrow's affair—W. sure that "no hindrance could be expected now." Then good night and home again.

Morse writes me. When I showed it to W., he said, "The grand Sidney! What a touch comes of his least word!" Chubb also writes me to this effect: Farmington, Conn. Sat. morning. Dear Traubel, I have been in the most unproductive mood since I arrived here, & have no little speech to send you for to-morrow's occasion. I wish I could be with you in person, but my spirit must do instead. Please convey my affectionate greetings to Whitman. May he live on among us for many a happy year to illustrate the majesty & peace of old age as he has illustrated the splendors of full-blooded manhood! I think of him in his serene latter days along with the gracious picture of old Cephalus, which Plato gives in the first pages of the Republic—enjoying "the abiding presence of sweet hope, that 'kind muse of old age' as Pindar calls it." The longer I live the more important does the birth of Whitman into the XIX Century appear to be. He is for me one of its few great emancipators from the special dangers to which it has been liable—the dangers of luxury and mechanism, issuing in the vice of dilettantism which at present afflicts certain American as well as European centres. The future will assuredly be grateful to Whitman for confronting his age with a type of manhood that exhibited a noble power, an emotional amplitude, a religiousness, a physical sanity, & simplicity of habit & carriage against which the influences of the time conspired in vain. I say the future will be grateful because I think that, like other great souls Whitman has been "before his time"; & that his influence upon the world has hardly been felt as yet. It will be felt, because the world is going to recover from its stupor of soul; & then it will recognise its liberators. I join with you in wishing joy to our dear friend & helpful elder comrade. Health & happiness to him & to you all! My particular congratulations to you on your marriage. Being a lover, with the hope of marriage before me, I can wish you well with deep sympathy. May all good things attend you & your wife in happy & prosperous wedlock! Send me November Boughs. I think I'll wait until Good-bye is bound to match—though if you have the sheets to spare I should like to see them, being minded to write a review. I enclose cheque for 2.50; if that proves insufficient, I'll send balance. What about the pocket Whitman? Farewell, my dear fellow. Percival Chubb W. gives me also a couple of Johnston's letters—thinks they would interest me—pertaining more or less to the New England Magazine article.

Bucke admits that his yesterday's judgment of W.'s condition was "ridiculous," for "he seems all tuckered out—rags—nothing of him."