Friday, June 15, 1888.

Friday, June 15, 1888.

Took to Ferguson proofs of Sands to page thirty-six, approved. Received in return from Ferguson three galleys on the Burns essay. Wrote to Bucke. [See indexical note p330.1] W. says: "Keep Doctor informed about things here: don't make the situation any worse than it is—make it a trifle better. Doctor is inclined to extreme views himself." In with W. at 7.45 evening. Found him alone fumbling about his room for a match. My offer to light the gas was rejected, though he used my arm to assist him in doing the thing for himself. He is game. "I won't be helped unless I must be." He asked at once: "Is it true that Frederick is dead? [See indexical note p330.2] Ah yes? It was to have been expected. And what a time there must be in Berlin tonight! I am not so sure of Germany now. There'll be a year or so's grief, or awe, following their loss, and then—who can tell what? [See indexical note p330.3] I have no faith in the young emperor now coming on—in William: he is a proud, narrow martinet—no more: a man who knew so little as not to respect a father and mother noble perhaps beyond the measure of any who ever reigned: a man the reverse of his father in all the good things for which the father stood. I thought we had some reasons for believing that Frederick would make Germany a peace nation." I asked: "But what about getting rid of the kings altogether?" [See indexical note p330.4] "That will come, too: the whole business will go. Meanwhile, we like the best kings better than the worst kings."

W. had read no proofs today but had worked on the Hicks. "I desire to get this into some final shape," he said: "I do not deny I am anxious about it—very anxious. For instance, if I got another blow like that the other day where would it leave me? [See indexical note p330.5] Way up the shore probably—I wouldn't be worth a damn from that time on: indeed, it might finish me right then and there. Now that I am better I am getting back the impulse to work. The Doctor says my pulse is good—very good—indeed, immensely good: and today I have had an effective bowel passage which seems to have cleared up the weather. It is wonderful, when you come to think of it, how much of a man is centred in his belly: the belly is the radiant force distributing life." [See indexical note p331.1] Then again: "I always feel tired. Although I am much better than yesterday I still rest under the old cloud—contend with the old indisposition to move about and work. I spoke awhile ago of the 'impulse' to work. It is hardly that—it is rather necessity. I want to see November Boughs through. Your sister sent me some more of her homemade cream, and oh! it is so deliciously taking! Cookery is so much of it genius—an art, by itself—one of six, one of ten, perhaps even more, only can do it justice. [See indexical note p331.2] How much is in a good bowl of coffee, a pot of potatoes—done just right. Some of my best experiences that way were among the soldiers—not always, but often: the whole affair going together—men, the place, everything. Your sister is an artist: she not only knows how to cook—she seems to know when I want particular things."

W. gave me a handful of letters received today and yesterday. "Look them through—answer them; they are all so sweet to me. Explain that I am too disabled to write myself just now. O'Connor has written but about nothing in particular. [See indexical note p331.3] I still remember Frank's visit yesterday: he came with his wife: Frank is always fortifying." W. laughs more than a little at the newspaper reports. "Do you see the papers? According to the papers I am crazy, dead, paralyzed, scrofulous, gone to pot in piece and whole: I am a wreck from stem to stern—I am sour, sweet—dirty, clean—taken care of, neglected: God knows what I am, what I am not. [See indexical note p331.4] The American newspaper beats the whole world telling the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth! But the Post account tonight—look it up there in the personal column"—indicating a paper—"is the fairest I have seen. Bonsall prints only a few conservative words probably inspired by Baker here. The Springfield Republican represents me as being in 'violent delirium' Sunday night."

Morse writes about his mother. [See indexical note p332.1] Mothers always make a special appeal to W. "I know of nothing more beautiful, inspiring, significant: a hale old woman, full of cheer as of years, who has raised a brood of hearty children, arriving at last at the period of rest, content, contemplation—the thought of things done." Someone across the street thrums a good deal on a piano. After W. has heard this for continuous hours some days he grows irritable. "She can beat the devil for noise and give him odds." Harned in in the forenoon. [See indexical note p332.2] "Tom brought in a will, embodying monetary and literary provisions—read it to me: it is about what I want. He has doubts about the legality of the will I made for myself. Tom is all right—I see his motive. I kept the will—took it from him—tucked it under my pillow: it is a matter that must be rightly attended to sometime—brought to a head." I saw both of the wills thrown carelessly open on the table. "A confusion of wills," W. calls it.

W. kicks a good deal about visitors. "Visitors," he says, "are so severe a strain, every one seems like half a dozen. [See indexical note p332.3] It is an ominous fact that I cannot stand visitors—the most ominous fact of all—because visitors, friends, lovers, comrades, whatever, are the last things I want to give up. But what can I do with this constant lethargy, languidness, drowsiness, tendency to sleep (when I do not sleep) hanging over me? Sometimes I seem sentenced to death: everything but the date is fixed."

W. said: "You are doing much too much for me nowadays. What can I do for you?" [See indexical note p332.4] "I am not doing anything for you. I am doing everything for myself." W. looked at me fixedly for a moment. Then he reached forward and took my hand. "I see what you mean, Horace. That is the right way to look at it. People used to say to me: Walt, you are doing miracles for those fellows in the hospitals. I wasn't. I was, as you would say, doing miracles for myself: that was all. One thing is sure—we seem to be able to work together in the right spirit."

W. never much interested in Stevenson's W. W. essay. [See indexical note p333.1] Said of it today: "Stevenson had a Leaves of Grass spasm: it mostly passed off, I should say: I am always Walt Whitman with an 'if' to some people." This matter came up because W. had found an old Burroughs letter in which the essay was referred to. "The essay and other things," explained W. "You will notice that he mentions Alcott, also. Alcott was always my friend: I have some letters here from Alcott that I want you to see some time. [See indexical note p333.2] It is curious about Emerson that no one who lived close to him ever claimed that he went back on his original opinion of Leaves of Grass."

West Park, Oct. 29, '82. Dear Walt.[See indexical note p333.3] I was much disturbed by your card. I had been thinking of you as probably enjoying these superb autumn days down in the country at Kirkwood, and here you are wretched and sick at home. I trust you are better now. You need a change. I dearly wish that as soon as you are well enough you would come up here and spend a few weeks with us. We could have a good time here in my bark-covered shanty and in knocking about the country. Let me know that you will come.

The Specimen Days &c came all right. I do not like the last part of the title; it brings me up with such a short turn. [See indexical note p333.4] I have read most of the new matter and like it of course. I have not seen any notices of the book yet. I have just received an English book—Familiar Studies of Men and Books—by Stevenson with an essay upon you in it. [See indexical note p333.5] But it does not amount to much. He has the American vice of smartness and flippancy. I do not think you would care for the piece.

I am bank examining nowadays but shall be free again pretty soon.

O'Connor writes me that he is going to publish his Tribune letters in a pamphlet, with some other matter; I am glad to hear it. [See indexical note p334.1] He draws blood every time.

I fear poor old Alcott will not rally; indeed he may be dead now. I had a pleasant letter from him the other day. [See indexical note p334.2] I had sent him a crate of Concord grapes.

I am very stupid today. For the past two weeks my brain has been ground between the upper and nether millstones of bank ledgers and it is sore. We are all well. Julian is a fine large boy. Drop me a card when you receive this; also write me when you will come up.

With much love, John Burroughs.

[See indexical note p334.3]

"Well, did you care for the piece?" I asked W. "Yes and no—yes, because it was intended to be friendly—no, because it was not very inclusive. Stevenson left so much of me unaccounted for—so very much: accounted for himself better than for me." Had O'Connor ever put the Tribune articles together? "No—that never happened. A half dozen of O'Connor's pieces bound in one book would have seemed like a battery of guns. [See indexical note p334.4] O'Connor never fell short of—never went beyond—his enemy: he inevitably fired to the right spot. He was a born artillerist—he was a past master in controversy: O'Connor anyhow was a host—O'Connor with the truth was all the hosts made into one." He reverted to Burroughs. [See indexical note p334.5]

"John is a milder type—not the fighting sort—rather more contemplative: John goes a little more for usual, accepted, respectable things, than we do—rather more: just a bit maybe—though God knows he is not enough respectable to hurt—not usual enough to get out of our company."

[See indexical note p334.6] Again: "The best of John is not in the cities—the best of him is in the woods: he gets

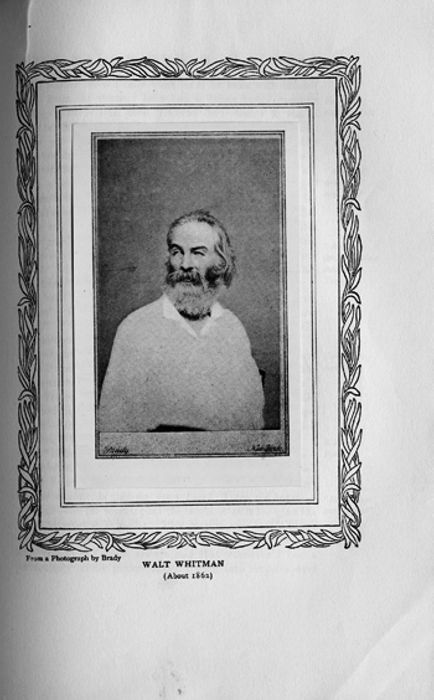

Walt Whitman (About 1862)

to be wholly himself only when he is let loose with himself away from the towns. [See indexical note p335.1] John has a rather better concrete feeling towards men than Thoreau had—seems to me to have better learned the lessons of the open air." Asked me: "Are you writing some yourself right along? Don't stop your writing: you will soon be on good terms with yourself: difficult things will come easier, easier, easy. [See indexical note p335.2] Above all, write your own way: don't take my word for anything—anyone's word—just take your own; follow your own intuition about it all, feeling sure that in the long run no other guide can lead you so surely to the truth." Was advice never good? He laughed quietly and concluded: "Certain things advised may be good, but advice?—no, it is never good! [See indexical note p335.3] Advice forces its way into the temple—it don't belong there."

Walt Whitman (About 1862)

to be wholly himself only when he is let loose with himself away from the towns. [See indexical note p335.1] John has a rather better concrete feeling towards men than Thoreau had—seems to me to have better learned the lessons of the open air." Asked me: "Are you writing some yourself right along? Don't stop your writing: you will soon be on good terms with yourself: difficult things will come easier, easier, easy. [See indexical note p335.2] Above all, write your own way: don't take my word for anything—anyone's word—just take your own; follow your own intuition about it all, feeling sure that in the long run no other guide can lead you so surely to the truth." Was advice never good? He laughed quietly and concluded: "Certain things advised may be good, but advice?—no, it is never good! [See indexical note p335.3] Advice forces its way into the temple—it don't belong there."

W. said he and Baker were "getting along famously together." But he hated the idea of "being under watch and ward." "When a man comes to my pass he'd best take the next step as quickly as possible." "But you seem in no hurry to take the step." [See indexical note p335.4] "Except for the work we have to do I would be quite willing—ready—even anxious to take the next step. But that work—that work: we must get it done before I write down 'finis' next my name." Kissed W. good night. He was weak but pretty clear about things. Tired—overslow in talk—finding it hard to gather himself together. W. gave me a Brady portrait of himself. I said: "It has a rather ascetic look for you." [See indexical note p335.5] "So it has—a sort of Moses in the burning bush look. Somebody used to say I sometimes wore the face of a man who was sorry for the world. Is this my sorry face? [See indexical note p335.6] I am not sorry—I am glad—for the world: glad the world is as it is—glad the world is what it is to be. This picture was much better when it was taken—it has faded out: I always rather favored it. William O'Connor always said that whenever I had a particularly idiotic picture taken I went into raptures over it. There may be good reasons for that: how often I have been told I was a particularly idiotic person!"