Saturday, June 16, 1888.

Saturday, June 16, 1888.

Twice at W.'s today. He was free enough of pain but not specially talkative. [See indexical note p336.1] Drowsy, he says, most of the time. "I go from my bed to the chair—from my chair to the bed—again and again—never staying long in either place, never losing altogether the sense of lethargy which characterizes my present condition. [See indexical note p336.2] My head feels so sore—so raw: for a minute or two at a time, now and then, relieved—but then sore again—sore!" Spoke of the death of Mary N. Spofford—then of Dick Spofford, saying of him: "Do you know him? Have you met him? He is a brainy fellow—honest: seems to be generally liked: is often in Washington, cavorting about with the big political guns: a lawyer—a lawyer, I should say, of ability and income. [See indexical note p336.3] I always feel that Dick is a sincere friend."

W. asked me to write to Burroughs and Kennedy. "I cannot do it: I am not equal to it." Had, however, sent notes to O'Connor and Bucke—"then I was worn out—could not go on." Adding: "Now you go on for me." Talked of Burroughs: "You would like John—should know him. [See indexical note p336.4] You might say that you write for me. John is simple, amiable, devoted. Tell him I am physically on the rack but that I am in good hands." His head, he said, was easier when he laid down. Could not handle the proofs today. "I no sooner take them up than I am overcome again by this damned lassitude."

I had met Brinton. [See indexical note p336.5] Said so to W. He was remarkably alert at once. "Tell me about the Doctor. Is he quite well? Did he say anything about us?" "O yes, a lot. He was talking about the future of the Leaves." "Did he think they will have a future?" "I should judge that it was his impression that you would be very soon forgotten— or that you would last a very long while." "Did Brinton take sides?" "He said he thought you would last a very long while." [See indexical note p337.1] W. smiled merrily: "From a cool man of science that very long while is significant"—pausing an instant and proceeding: "That's my feeling too—has long been my feeling—that the Leaves are destined for a long life or are a dead failure."

W. called my attention to a clipping from the Chicago Herald, adversely commenting on his poetry. "That," said he, "is a slap in the face that does a fellow more good than a kiss." He is very cordial towards the enemy. [See indexical note p337.2] "They sail into me in great style—but that is the great test: if I cannot stand their attack I might as well go out of the Leaves business." "You are a rebel—you suffer from no attacks that you do not invite." "You are quite right: I am responsible, the people opposed to me are not responsible, for the fight—or, perhaps, we are both sides responsible. [See indexical note p337.3] I do not claim to be exempt."

Asked Mrs. Davis today to bring him up the N.A. Review Lincoln book and the little flexible Epictetus—Rolleston's. He will use his own essay on Lincoln in that volume in November Boughs. Wished to know if the printers could work from the book? [See indexical note p337.4] And would the N. A. R. people object to his including this in the book? "I am quite particular on the ethics of such a question: as, for instance, with The Century people and the two unprinted pieces, which they have paid for and not used." Epictetus appeals profoundly to W. Is always quoting the Enchiridion—quoting rather to the spirit than the letter. [See indexical note p337.5] He told Mrs. Davis when she brought books up from the parlor: "Now that the room is arranged I suppose I'll never be able to find anything any more."

Osler not here today. "He left word that we should send word over—we did so, telling him he was not needed." Is rather disturbed about the prolongation of his troubles. "I feel keenly my mental shakeup—my loss of continuity: my overwhelming weariness. I am afraid I am pretty well done for." [See indexical note p338.1] Baker suggested that he should have a bath but he said he would rather wait. "I am too weak: I am fragile enough to break." The day the big tin tub was brought in (it is round—four feet in diameter—about ten inches deep) he threw his head back on the pillows, opened his eyes wide and exclaimed: "Christ a'mighty! What's that?" No callers admitted today. Sat up and read papers. W. inquired of me concerning a deckhand at the ferry who had a sick wife. [See indexical note p338.2] Gave me a quarter to give Ben Hichens, a newsboy, who stands around the ferry on the Philadelphia side.

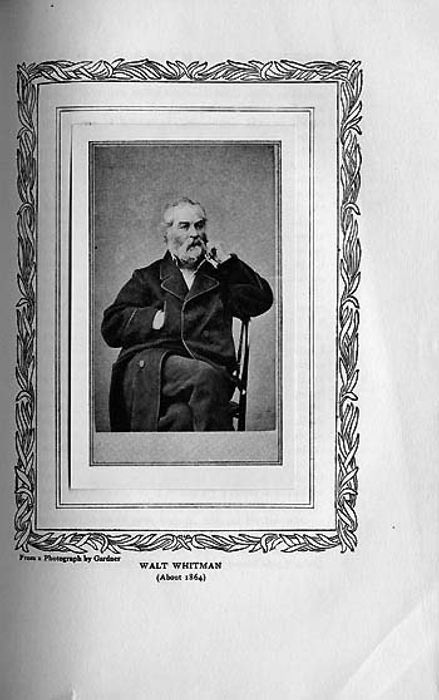

W. was very anxious about my mother who is a little under the weather. He had mislaid some of the proofs. We hunted them up on the round table by the window and got them together again. W. in the process shoved a couple of piles of documents over on the floor, I picking them up and returning them to the table. I asked him about a little portrait that turned up—a Washington portrait, made by Gardner. [See indexical note p338.3] He asked: "Would you like to have it? Very well—take it along. That's one of the several portraits which William O'Connor called the Hugo portraits. O'Connor and Burroughs never agreed about Hugo. When William spoke of the Hugo Whitmans John said he couldn't see it."

I picked up and asked him if I might read the draft of a letter written by him to Margaret S. Curtis, Boston. [See indexical note p338.4] The envelope was marked: "Care P. Curtis Oct. 28 '63 (about Caleb H. Babbitt)." He knew of my special interest in his hospital records. "Yes—read it—keep it, if you like. There's stuff in some of those letters which might make a certain sort of history. I have of course used some of the material in Specimen Days—some of it—but the letters possibly have a more absolutely concrete personal touch. I have lately destroyed a lot of that old mess of notes"—I

Walt Whitman (About 1864)

broke in: "What the devil do you do that for?" He laughed outright: "Now you're fierce again—why, you're as bad as Bucke and O'Connor. [See indexical note p339.1] What the hell's all that stuff good for now except to lumber up the house? Go down stairs and ask Mary if that ain't so." I was serious about it: "Anyway—let me judge of that for myself. I've got plenty of room home for anything you want to throw away." He looked at me fixedly: "You seem to be very earnest about it. [See indexical note p339.2] I don't know that I've got any prejudice against saving it. But, Horace—most of that stuff is best destroyed—for many reasons best." I still insisted. Then he smiled and concluded: "I'll promise to throw some of it your way—some of it—though there is a bit here and there too sacred—too surely and only mine—to be perpetuated. [See indexical note p339.3] I think you must understand that: anything else you are welcome to."

Walt Whitman (About 1864)

broke in: "What the devil do you do that for?" He laughed outright: "Now you're fierce again—why, you're as bad as Bucke and O'Connor. [See indexical note p339.1] What the hell's all that stuff good for now except to lumber up the house? Go down stairs and ask Mary if that ain't so." I was serious about it: "Anyway—let me judge of that for myself. I've got plenty of room home for anything you want to throw away." He looked at me fixedly: "You seem to be very earnest about it. [See indexical note p339.2] I don't know that I've got any prejudice against saving it. But, Horace—most of that stuff is best destroyed—for many reasons best." I still insisted. Then he smiled and concluded: "I'll promise to throw some of it your way—some of it—though there is a bit here and there too sacred—too surely and only mine—to be perpetuated. [See indexical note p339.3] I think you must understand that: anything else you are welcome to."

W. looked pretty tired. Baker floated in and out as we talked. I opened the Curtis envelope. W. said: "Put that up—read it when you get home. I am going to ask you now to help me to the bed and put down the light." This I did. W. then said: "Kiss me good night!" finally crying to me as I stood as the door: "Go to Ferguson! [See indexical note p339.4] Oh, tomorrow's Sunday! That's so. God bless you!" I asked Baker as I left what he thought generally of W.'s condition. "He is making slow advances—he will pull through." Back home—wrote a whole batch of letters for W., to people he had mentioned. Then sat down and read the Curtis letter:

Dear Madam.[See indexical note p339.5] Since I last wrote you I have continued my hospital visitations daily or nightly without intermission and shall continue them this fall and winter. Your contributions, and those of your friends, sent me for the soldiers wounded and sick, have been used among them in manifold ways, little sums of money given, (the wounded very generally come up here without a cent and in lamentable plight,) and in purchases of various kinds, often impromptu as I see things wanted on the moment [break] . . . train is standing tediously waiting, &c. as they often are here. [See indexical note p340.1] But what I write this note for particularly is to see if your sister, Hannah Stevenson, or yourself, might find it eligible to see a young man whom I love very much, who has fallen into deepest affliction, and is now in your city. He is a young Massachusetts soldier from Barre. [See indexical note p340.2] He was sun-struck here in Washington last July, was taken to hospital here, I was with him a good deal for many weeks—he then went home to Barre,—became worse,—has now been sent from his home to your city—is at times (as I infer) so troubled [break] . . . I received a letter from Boston this morning from a stranger about him telling me (he appears too ill to write himself) that he is in Mason General Hospital, Boston. His name is Caleb H. Babbitt of Co E 34th Mass Vol. He must have been brought there lately. My dear friend, if you should be able to go, or if not able yourself give this to your sister or some friend who will go,—it may be that my dear boy and comrade is not so very bad, but I fear he is. [See indexical note p340.3] Tell him you come from me like, and if he is in a situation to talk, his loving heart will open to you at once. He is a manly, affectionate boy. I beg whoever goes would write a few lines to me how the young man is. I send my thanks and love to yourself, your sister, husband, and the sisters Wigglesworth. Or else give this to Dr. Russell. The letter from the stranger above referred to is dated also Pemberton square hospital.